Between Revolutions: the 1830S and 1840S Even Though No Major

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Political Story, 1814-1900

The Political Story: 1815-1900. From Monarchy to Republic, the struggle for stability and compromise • Republicanism a minority allegiance up to 1880 • Critics associate it with Jacobinism, violent democracy, “Bolshevism” in its day. • By 1880, a permanent majority of the French converted to the republican ideal (Wright, 205) • Transition was exceptional, not normal, it its day A series of experiments in search of stability and compromise (Wright) • The Bourbon Experiment (1814-1830) • The Orléanist Experiment (1830-1848) • The Republican Experiment (1848-1852) • The Imperial Experiment (1852-1870) • The Rooting of the Republican System (1870-1919) Louis XVIII, King of France (1814-1824) Louis-Philippe, King of the French, 1830-1848 Official portrait of Louis XVIII by Jean-Baptiste-Louis Gros Official portrait by Franz Xavier Winterhalter, 1839 Louis XVIII and the Royal Family Charles X, King of France 1824-1830 Official portrait François GERARD, 1825 1814-1848 Struggles for Compromise that Failed How to blend the Revolution and the Old Regime? How to bridge deep divisions created by the Revolution? • Louis XVIII (1814-1824) & the Charter—divine right and a nobility with a legislature • 1817—90,000 men of the wealthy elite had the right to vote • The Chamber: ultras, moderates, liberals (constitutional monarchists, a few republicans) • Charles X (1824-1830) “Stubbornly Unwise” • Coronation at Reims (symbol of the Old Regime) • Compensation of noble émigrés • Partial restoration of the Church—seminaries and missions • Trio of unpopular -

Hamilton's Forgotten Epidemics

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics / D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-9782417-4-2 Print catalogue data is available from Library and Archives Canada, at www.collectionscanada.gc.ca Cover Image: Historical City of Hamilton. Published by Rice & Duncan in 1859, drawn by G. Rice. http://map.hamilton.ca/old hamilton.jpg Cover Design: Robert Huang Group Photo: Temara Brown Ch2olera Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles, editors DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY McMASTER UNIVERSITY Hamilton, Ontario, Canada Contents FIGURES AND TABLES vii Introduction Ch2olera: Hamilton’s Forgotten Epidemics D. Ann Herring and Heather T. Battles 2 2 “From Time Immemorial”: British Imperialism and Cholera in India Diedre Beintema 8 3 Miasma Theory and Medical Paradigms: Shift Happens? Ayla Mykytey 18 4 ‘A Rose by Any Other Name’: Types of Cholera in the 19th Century Thomas Siek 24 5 Doesn’t Anyone Care About the Children? Katlyn Ferrusi 32 6 Changing Waves: The Epidemics of 1832 and 1854 Brianna K. Johns 42 7 Charcoal, Lard, and Maple Sugar: Treating Cholera in the 19th Century S. Lawrence-Nametka 52 iii 8 How Disease Instills Fear into a Population Jacqueline Le 62 9 The Blame Game Andrew Turner 72 10 Virulence Victims in Victorian Hamilton Jodi E. Smillie 80 11 On the Edge of Death: Cholera’s Impact on Surrounding Towns and Hamlets Mackenzie Armstrong 90 12 Avoid Cholera: Practice Cleanliness and Temperance Karolina Grzeszczuk 100 13 New Rules to Battle the Cholera Outbreak Alexandra Saly 108 14 Sanitation in Early Hamilton Nathan G. -

I Padri Della Patria: Cattaneo, Gioberti, Pisacane, Cavour, Mazzini, Garibaldi

Percorsi bibliografici nelle collezioni della Biblioteca del Senato I padri della patria Biblioteca del Senato “Giovanni Spadolini” Carlo Cattaneo Bibliografia orientativa (1997 - 2010) I testi sono elencati in ordine cronologico inverso e per autore e titoli. ***************************************************************************** Carlo Cattaneo, Stati Uniti d'Italia. Scritti sul federalismo democratico, Roma, Donzelli, 2010. (Governo gen. 233) Clelia Pighetti, A Milano nell'Ottocento: il lavorio scientifico e il giornalismo di Carlo Cattaneo, Milano, Franco Angeli, 2010. (266. X. 8) Paolo Bagnoli, L'idea dell'Italia: 1815-1861, Reggio Emilia, Diabasis, 2007. (262. XVIII. 5) Carlo Cattaneo, Civilization and democracy. The Salvemini anthology of Cattaneo's writings, Toronto, University of Toronto press, 2006. (261. XXII. 55) Il Politecnico di Carlo Cattaneo: la vicenda editoriale, i collaboratori, gli indici, a cura di Carlo G. Lacaita, Lugano-Milano, Casagrande, 2005. (Giornalismo Italia. Spec. P. 3) Carlo Cattaneo: i temi e le sfide, a cura di Arturo Colombo, Franco Della Peruta e Carlo G. Lacaita, Milano, Casagrande, 2004. (147. VII. 84) Lauretta Colucci, Carlo Cattaneo nella storiografia. Studi su Risorgimento e federalismo dal 1869 al 2002, Milano, Giuffrè, 2004. (Collez. ital. 2556. IV. 6) Cattaneo e Garibaldi: federalismo e Mezzogiorno, a cura di Assunta Trova e Giuseppe Zichi, Roma, Carocci, 2004. (Collez. ital. 2609. 23) Armani Giuseppe, Cattaneo riformista: la linea del "Politecnico", Padova, Marsilio, 2003. (123. XI. 48) La biblioteca di Carlo Cattaneo, a cura di Carlo G. Lacaita, Raffaela Gobbo e Alfredo Turiel, Bellinzona, Casagrande, 2003. (Collez. ital. 2321. 10) Ettore Rotelli, L' eclissi del federalismo. Da Cattaneo al Partito d'azione, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2003. (Governo Italia 42) Becattini Giacomo, I nipoti di Cattaneo. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

Hoosiers and the American Story Chapter 3

3 Pioneers and Politics “At this time was the expression first used ‘Root pig, or die.’ We rooted and lived and father said if we could only make a little and lay it out in land while land was only $1.25 an acre we would be making money fast.” — Andrew TenBrook, 1889 The pioneers who settled in Indiana had to work England states. Southerners tended to settle mostly in hard to feed, house, and clothe their families. Every- southern Indiana; the Mid-Atlantic people in central thing had to be built and made from scratch. They Indiana; the New Englanders in the northern regions. had to do as the pioneer Andrew TenBrook describes There were exceptions. Some New Englanders did above, “Root pig, or die.” This phrase, a common one settle in southern Indiana, for example. during the pioneer period, means one must work hard Pioneers filled up Indiana from south to north or suffer the consequences, and in the Indiana wilder- like a glass of water fills from bottom to top. The ness those consequences could be hunger. Luckily, the southerners came first, making homes along the frontier was a place of abundance, the land was rich, Ohio, Whitewater, and Wabash Rivers. By the 1820s the forests and rivers bountiful, and the pioneers people were moving to central Indiana, by the 1830s to knew how to gather nuts, plants, and fruits from the northern regions. The presence of Indians in the north forest; sow and reap crops; and profit when there and more difficult access delayed settlement there. -

Mcq Drill for Practice—Test Yourself (Answer Key at the Last)

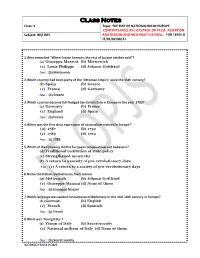

Class Notes Class: X Topic: THE RISE OF NATIONALISM IN EUROPE CONTENTS-MCQ ,FILL UPS,TRUE OR FALSE, ASSERTION Subject: HISTORY AND REASON AND MCQ PRACTICE DRILL… FOR TERM-I/ JT/01/02/08/21 1.Who remarked “When France Sneezes, the rest of Europe catches cold”? (a) Giuseppe Mazzini (b) Metternich (c) Louis Philippe (d) Johann Gottfried Ans : (b) Metternich 2.Which country had been party of the ‘Ottoman Empire’ since the 15th century? (b) Spain (b) Greece (c) France (d) Germany Ans : (b) Greece 3.Which country became full-fledged territorial state in Europe in the year 1789? (c) Germany (b) France (c) England (d) Spain Ans : (b) France 4.When was the first clear expression of nationalism noticed in Europe? (a) 1787 (b) 1759 (c) 1789 (d) 1769 Ans : (c) 1789 5.Which of the following did the European conservatives not believe in? (d) Traditional institution of state policy (e) Strengthened monarchy (f) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days Ans : (c) A return to a society of pre-revolutionary days 6.Name the Italian revolutionary from Genoa. (g) Metternich (b) Johann Gottfried (c) Giuseppe Mazzini (d) None of these Ans : (c) Giuseppe Mazzini 7.Which language was spoken for purposes of diplomacy in the mid 18th century in Europe? (h) German (b) English (c) French (d) Spanish Ans : (c) French 8.What was ‘Young Italy’ ? (i) Vision of Italy (b) Secret society (c) National anthem of Italy (d) None of these Ans : (b) Secret society WORKED FROM HOME 9.Treaty of Constantinople recognised .......... as an independent nation. -

French Romantic Socialism and the Critique of Liberal Slave Emancipation Naomi J

Santa Clara University Scholar Commons History College of Arts & Sciences 9-2013 Breaking the Ties: French Romantic Socialism and the Critique of Liberal Slave Emancipation Naomi J. Andrews Santa Clara University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.scu.edu/history Part of the European History Commons, and the Feminist, Gender, and Sexuality Studies Commons Recommended Citation Andrews, Naomi J. (2013). Breaking the Ties: French Romantic Socialism and the Critique of Liberal Slave Emancipation. The ourJ nal of Modern History, Vol. 85, No. 3 (September 2013) , pp. 489-527. Published by: The nivU ersity of Chicago Press. Article DOI: 10.1086/668500. Article Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/668500 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Arts & Sciences at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in History by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Breaking the Ties: French Romantic Socialism and the Critique of Liberal Slave Emancipation* Naomi J. Andrews Santa Clara University What we especially call slavery is only the culminating and pivotal point where all of the suffering of society comes together. (Charles Dain, 1836) The principle of abolition is incontestable, but its application is difficult. (Louis Blanc, 1840) In 1846, the romantic socialist Désiré Laverdant observed that although Great Britain had rightly broken the ties binding masters and slaves, “in delivering the slave from the yoke, it has thrown him, poor brute, into isolation and abandonment. Liberal Europe thinks it has finished its work because it has divided everyone.”1 Freeing the slaves, he thus suggested, was only the beginning of emancipation. -

A British Reflection: the Relationship Between Dante's Comedy and The

A British Reflection: the Relationship between Dante’s Comedy and the Italian Fascist Movement and Regime during the 1920s and 1930s with references to the Risorgimento. Keon Esky A thesis submitted in fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences. University of Sydney 2016 KEON ESKY Fig. 1 Raffaello Sanzio, ‘La Disputa’ (detail) 1510-11, Fresco - Stanza della Segnatura, Palazzi Pontifici, Vatican. KEON ESKY ii I dedicate this thesis to my late father who would have wanted me to embark on such a journey, and to my partner who with patience and love has never stopped believing that I could do it. KEON ESKY iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This thesis owes a debt of gratitude to many people in many different countries, and indeed continents. They have all contributed in various measures to the completion of this endeavour. However, this study is deeply indebted first and foremost to my supervisor Dr. Francesco Borghesi. Without his assistance throughout these many years, this thesis would not have been possible. For his support, patience, motivation, and vast knowledge I shall be forever thankful. He truly was my Virgil. Besides my supervisor, I would like to thank the whole Department of Italian Studies at the University of Sydney, who have patiently worked with me and assisted me when I needed it. My sincere thanks go to Dr. Rubino and the rest of the committees that in the years have formed the panel for the Annual Reviews for their insightful comments and encouragement, but equally for their firm questioning, which helped me widening the scope of my research and accept other perspectives. -

5 How Did Nationalism Lead to a United Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815

#5 How did nationalism lead to a united Italy? Congress of Vienna--1815 • Italy had been divided up • Controlled by ruling families of Austria, France & Spain • Secretive group of revolutionaries formed in S. Italy – inspired by French Rev. 1848 • Nationalistic feelings were intensifying– throughout the 8 Italian city-states • Revolts were led by Giuseppe Mazzini – returned from exile • Leader of the “Young Italy” movement – dedicated to securing “for Italy Unity, Independence & Liberty” These Revolts Failed • Looked to Kingdom of Sardinia to rule a unified Italy – agreed they would rather have a unified Italy with a monarch than a lot of foreign powers ruling over separate states • “Risorgimento” Count Cavour & King Victor Emmanuel II • Wanted to unify Italy – make Piedmont- Sardinia the model for unification • Began public works, building projects, political reform • Next step -- get Austria out of the Italian Peninsula • Outbreak of Crimean War -- France & Britain on one side, Russia on the other • Piedmont-Sardinia saw a chance to earn some respect and make a name for itself • They were victorious and Sardinia was able to attend the peace conference. As a result of this, Piedmont- Sardinia gained the support of Napoleon III. Giuseppe Garibaldi • Italian Nationalist • Invaded S. Italy with his followers, the Red Shirts • Also supported King Victor Emmanuel – Piedmont Sardinia was only nation capable of defeating Austria • Aided by Sardinia – Cavour gave firearms to Garibaldi • Guerrilla warfare (hit & run tactics) Unified Italy • Constitutional monarchy was established – Under King Victor Emmanuel • Rome – new capital • Pope went into “exile” Garibaldi And Victor Emmanuel "Right Leg in the Boot at Last" Problems of Unification • Inexperience in self- government • Tradition of regional independence • Large part of population was illiterate • Lots of debt • Had to build an infrastructure • Severe economic & cultural divisions • (S – poor, N – more industrialized) • Centralized state, but weak Independence • Lots of people left for the U.S. -

THE ECONOMY of CANADA in the NINETEENTH CENTURY Marvin Mcinnis

2 THE ECONOMY OF CANADA IN THE NINETEENTH CENTURY marvin mcinnis FOUNDATIONS OF THE NINETEENTH- CENTURY CANADIAN ECONOMY For the economy of Canada it can be said that the nineteenth century came to an end in the mid-1890s. There is wide agreement among observers that a fundamental break occurred at about that time and that in the years thereafter Canadian economic development, industrialization, population growth, and territorial expansion quickened markedly. This has led economic historians to put a special emphasis on the particularly rapid economic expansion that occurred in the years after about 1896. That emphasis has been deceptive and has generated a perception that little of consequence was happening before 1896. W. W. Rostow was only reflecting a reasonable reading of what had been written about Canadian economic history when he declared the “take-off” in Canada to have occurred in the years between 1896 and 1913. That was undoubtedly a period of rapid growth and great transformation in the Canadian economy and is best considered as part of the twentieth-century experience. The break is usually thought to have occurred in the mid-1890s, but the most indicative data concerning the end of this period are drawn from the 1891 decennial census. By the time of the next census in 1901, major changes had begun to occur. It fits the available evidence best, then, to think of an early 1890s end to the nineteenth century. Some guidance to our reconsideration of Canadian economic devel- opment prior to the big discontinuity of the 1890s may be given by a brief review of what had been accomplished by the early years of that decade. -

History of American Democracy Syllabus

History of American Democracy Course Syllabus Professor David Moss Fall 2015 HISTORY OF AMERICAN DEMOCRACY (USW 39, HBS 1139) Professor David Moss Harvard University, Fall 2015 Mondays and Wednesdays, 3:30-5:00 Location: HBS – Aldrich 207 Today we often hear that American democracy is broken—but what does a healthy democracy look like? How has American democratic governance functioned in the past, and how has it changed over time? This course approaches American history with these questions in mind. Based on the case method, each short reading will introduce students to a different critical episode in the development of American democracy, from the drafting of the Constitution to contemporary fights over same-sex marriage. The discussion-based classes will encourage students to challenge each other’s assumptions about democratic values and practices, and draw their own conclusions about what “democracy” means in America. This course is ideal for anyone interested in deepening his or her practical and historical understanding of the American political process, and for those interested in gaining experience with the case method of instruction frequently used in business and law schools. Note: This course, when taken for a letter grade, satisfies the General Education category of United States in the World, as well as the requirement that one of the eight General Education courses also engage substantially with Study of the Past. When taken for a letter grade, it also meets the Core area requirement for Historical Study A. COURSE ORGANIZATION AND OBJECTIVES The course content surveys key episodes in the development of democratic institutions and practices in the United States from the late 18th century to today. -

The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat

The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat To cite this version: Samuel Hayat. The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism. History of Political Thought, Imprint Academic, 2015, 36 (2), pp.331-353. halshs-02068260 HAL Id: halshs-02068260 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-02068260 Submitted on 14 Mar 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. History of Political Thought, vol. 36, n° 2, p. 331-353 PREPRINT. FINAL VERSION AVAILABLE ONLINE https://www.ingentaconnect.com/contentone/imp/hpt/2015/00000036/00000002/art00006 The Revolution of 1848 in the History of French Republicanism Samuel Hayat Abstract: The revolution of February 1848 was a major landmark in the history of republicanism in France. During the July monarchy, republicans were in favour of both universal suffrage and direct popular participation. But during the first months of the new republican regime, these principles collided, putting republicans to the test, bringing forth two conceptions of republicanism – moderate and democratic-social. After the failure of the June insurrection, the former prevailed. During the drafting of the Constitution, moderate republicanism was defined in opposition to socialism and unchecked popular participation.