An Analysis of Korean Reported Speech in Media Talk

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Treatment Strategies and Communication Techniques 183 ACTION STEPS: Finding the Right Therapist 189 ACTION STEPS: General Approaches to Communication 197

i-x.kreisman..fm 12/26/03 4:22 PM Page i Sometimes I Act Crazy Living with Borderline Personality Disorder Jerold J. Kreisman, M.D. Hal Straus John Wiley & Sons, Inc. i-x.kreisman..fm 12/26/03 4:22 PM Page vi i-x.kreisman..fm 12/26/03 4:22 PM Page i Sometimes I Act Crazy Living with Borderline Personality Disorder Jerold J. Kreisman, M.D. Hal Straus John Wiley & Sons, Inc. i-x.kreisman..fm 12/26/03 4:22 PM Page ii In memory of my father, Erwin Kreisman, and for my mother, Frieda Kreisman, who taught us that—with unconditional love—all things are possible. —JEROLD J. KREISMAN, M.D. For Lil and Lou —HAL S TRAUS Copyright © 2004 by Jerold J. Kreisman, M.D., and Hal Straus. All rights reserved Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey Published simultaneously in Canada No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com. Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hobo- ken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008. -

KBTV MEDIA KIT 2016 KBTV 소개 Vision

KBTV MEDIA KIT 2016 KBTV 소개 Vision HISTORY CEO 인사말 KBTV는 한국 국영방송사 KBS 컨텐츠 자원을 기반으로 미디어 컨텐츠 제작, 기타 미디어 서비스를 운영하는 미래형 종합 방송사입니다 또한 축적된 제작 경험을 바탕으로 보다 완성도 높은 작품을 통하여 급속히 변화하는 영상 시장을 선도 하고자 합니다 KBTV는 참신한 기획과 주도 면밀한 작업, 그리고 원활한 작품 제작 시스템을 구성하여 미래 지향적 컨텐츠 제작의 새로운 축을 만들어 가고자 합니다 KBTV CEO & CHAIRMAN 이동현 KBTV는 신뢰를 바탕으로 그 신뢰를 영원히 저버리지 않을 열정으로 컨텐츠 제작 산업의 선두 주자로 거듭나 세계를 움직이는 미디어가 되고자 합니다 KBTV는 TV 방송 제작 (뉴스, 다큐멘터리, 예능, 버라이어티, 드라마) 과 기업 영상 홍보물 및 TV 광고 제작, 콘서트, 컨벤션 등의 각종 이벤트를 오랜 경험을 바탕으로 최선을 다해 최고의 프로덕션을 제공 할것입니다 KBTV는 시청자의 눈으로 시청자를 위한 시청자와 함께하는 미국을 넘어 전 세계 한인 커뮤니티 대표 방송사로 거급날 것입니다 About KBS CHANNELS INTERNATIONAL BROADCASTING TV RADIO TERRESTIAL TV KBS initiated the country's first radio broadcasting service in 1924 RADIO Commenced Korea's first television broadcasting service in 1961 First broadcasting HD programs in 2001 RADIO1 RADIO2(HAPPY FM) KBS completed the transfer to digital broadcasting in 2012 RADIO3(VOICE OF LOVE) Gross revenue 1.568 trillion won CABLE TV FM1(CLASSIC FM) 2012 FM2(COOL FM) Total cost 1.5742 trillion won 2012 GLOBAL KOREAN NETWORK OVERVIEW TERRESTIAL DMB KBS has long been a leader in the development of the broadcasting culture of the nation. As the key public service broadcaster of Korea, KBS has undertaken initiatives at technological turning points while providing a communication channel for diverse views. In the multi-channel digital broadcasting environment, a number of broadcasting channels are available, making the social role of public broadcasting ever more important. -

Conversation Model Fine-Tuning for Classifying Client Utterances in Counseling Dialogues

Conversation Model Fine-Tuning for Classifying Client Utterances in Counseling Dialogues Sungjoon Park 1, Donghyun Kim 2, Alice Oh 1 1 School of Computing, KAIST, Republic of Korea 2 Trost, Humart Company, Inc., Republic of Korea [email protected], [email protected] [email protected] Abstract office and with reduced financial burden com- pared to traditional face-to-face counseling ses- The recent surge of text-based online coun- sions (Hull, 2015). seling applications enables us to collect and In text-based counseling, the communication analyze interactions between counselors and environment changes from face-to-face counsel- clients. A dataset of those interactions can ing sessions. The counselor cannot read non- be used to learn to automatically classify the client utterances into categories that help verbal cues from their clients, and the client uses counselors in diagnosing client status and pre- text messages rather than spoken utterances to dicting counseling outcome. With proper deliver their thoughts and feelings, resulting in anonymization, we collect counselor-client di- changes of dynamics in the counseling relation- alogues, define meaningful categories of client ship. Previous studies explored computational ap- utterances with professional counselors, and proaches to analyzing the dynamic patterns of re- develop a novel neural network model for clas- lationship between the counselor and the client sifying the client utterances. The central idea of our model, ConvMFiT, is a pre-trained con- by focusing on the language of counselors (Imel versation model which consists of a general et al., 2015; Althoff et al., 2016), clustering topics language model built from an out-of-domain of client issues (Dinakar et al., 2014), and look- corpus and two role-specific language models ing at therapy outcomes (Howes et al., 2014; Hull, built from unlabeled in-domain dialogues. -

Zeta Spring Copy

Chi Sigma Iota The University of Alabama at Birmingham CHI SIGMA IOTA The University of Alabama at Birmingham THES P E C I ALCOMPASS E D I T I O N Fall 2013 http://www.ed.uab.edu/csi-zeta/ Page 1 T H E C O M P A S S IN THIS ISSUE LETTER FROM ZETA PRESIDENT 1 A HelloLetter Counselor from Education Zeta Program President 2012 - 2013 eZeta v e n t s Letter from Zeta Students and Friends! planned for President I hope you all had a wonderful Executivethe fall and Board Officers 2 summer and that the fall semester early spring Zeta Counseling Ethics is finding you well. Zeta Chapter Olivia Dornas well, so Workshop has been busy with educational Presidentplease make New Student Orientation programs and social events. In sure you are June we hosted our annual ethics Aisha Holmesconnected 3-4 workshops attended by more than President Electand receiving Interview with Dr. Judith 85 counselors and students. Zeta our updates Chapter members came together Mallory McKeethrough the Harrington Past President during the summer to paint the Counselor 5 UAB Community Counseling Aisha Homes Education Pinning Ceremony Olivia Dorn David Murphree Student Orientation Clinic. We were excited to host listserv emails,Treasurer the Counselor Zeta members and CEP students Education Program website or 6 at an evening in Regions Park to Facebook page.Dan Stephens First Light Breakfast and Secretary Housewarming Shower watch the Barons, as well as a I would like to take this Welcome Back! event to kick off opportunityLizbeth to invite Graffeo new students 7 the new school year for new and Counselor’s View of Italy as well asMentorship those students Chair more returning students. -

Korean Broadcasting System

Not ogged in Ta k Contributions Create account Log in Artic e Ta k Read Edit Hiew history Search Wikipedia Korean Broadcasting System From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Coordinates : 3,.52538GN 12A.91A3A1GE This article may be expanded with text translated [show ] from the corresponding article in Korean . (September 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions. Korean Broadcasting System ( KBS ) Korean Broadcasting System (KBS) Main page Contents (Hangul : 한국방송공사 ; Hanja : 韓 7eatured content Current e2ents 國放送公社 ; RR : Han-guk Bangsong Random artic e Ionate to Gongsa ; MR : Han'guk Pangsong Kongsa ) is 6ikipedia 6ikipedia store the national public broadcaster of South Korea . It was founded in 1927, and operates Logo used since 2 October 1984 1nteraction radio , television , and online services, being He p one of the biggest South Korean television About 6ikipedia Community porta networks . Recent changes Contact page Contents [ hide ] Too s 1 History 1.1 Beginnings in radio 6hat inks here Re ated changes 1.2 1950s–1960s - Move into Up oad K e television Specia pages Permanent ink 1.3 1970s - Expansion Page information 1.4 1980s - Advertising started after Main building of Korean Broadcasting System 6ikidata item controversial merger Native name 한국방송공사 Cite this page 1.5 1990s - SpinoE of EBS Hanja 韓國放送公社 Print/eCport 2 Structure Revised Han-guk Bangsong Gongsa Create a book 3 CEOs Romanization Iown oad as PI7 Printab e 2ersion 4 Channe s McCune– Han'guk Pangsong Kongsa 4.1 Terrestria te evision Reischauer 1n other projects -

Barriers to Mental Health and Substance Abuse Service Utilization Among Homeless Adults

BARRIERS TO MENTAL HEALTH AND SUBSTANCE ABUSE SERVICE UTILIZATION AMONG HOMELESS ADULTS By MICHAEL D. BRUBAKER A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2009 1 © 2009 Michael D. Brubaker 2 To all of the women, men, and children who have lived without a home 3 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am truly grateful to Dr. Michael Garrett, my chair and advisor, for offering me a creative space to develop and grow as a researcher and human being. I am also thankful to each of my committee members: Dr. Ellen Amatea, who encouraged me to critically engage the existing body of research; Dr. Edil Torres Rivera, who introduced me to the ways of liberation psychology; and Dr. David Miller, who showed me the power of statistics and program evaluations as a way to serve those without permanent housing. I am thankful for the support of my family and friends, especially my parents, Dale and Barbara Brubaker. With good humor and constant encouragement, they have seen me through many challenges in both academics and life. As a supervisor and friend, Dr. James Bass inspired me to consider a career serving those without housing. I am truly thankful for Dr. Brian Dew and Dr. West-Olatunji for showing me how to make research meaningful for me and my community. I am incredible thankful for my two co-investigators on this research, Niyama Ramlall and TaJuana Chisholm. These two women showed endless courage as they walked into the unknown and patience as they put up with me. -

Star Channels Guide, Oct. 29-Nov. 4

OCTOBER 29 - NOVEMBER 4, 2017 staradvertiser.com HOLEY HUMOR Arthur (Judd Hirsch) and Franco (Jermaine Fowler) prepare to take on gentrifi cation, corporations and trendy food trucks in the humorously delicious sophomore season of Superior Donuts. Premieres Monday, Oct. 30, on CBS. Join host, Lyla Berg as she sits down with guests Meet the NEW SHOW WEDNESDAY! who share their work on moving our community forward. people SPECIAL GUESTS INCLUDE: and places Nate Gyotoku, Director of Sustainability Initiatives, KUPU that make Jerri Chong, President, Ronald McDonald House Charities of Hawaii 1st & 3rd Wednesday Desoto Brown, Historian, Bishop Museum Hawai‘i olelo.org of the Month, 6:30 pm Shari Chang, CEO of Girl Scouts of Hawaii Channel 53 special. Representative Jarrett Keohokalole ON THE COVER | SUPERIOR DONUTS Tasty yet topical Deliciously real laughs in alongside the shop as it continues to draw new customers with healthier breakfast alterna- faces in, while never losing sight of its regulars. tives, keeping in mind social and ethical prin- season 2 of ‘Superior Donuts’ The quick wit and bold approach to dis- ciples. The discussions surrounding millennials cussing modern issues make it unsurprising aren’t new for “Superior Donuts,” but the ad- By Kat Mulligan that the series is back for a second season. dition of Sofia provides yet another outlet for TV Media “Superior Donuts” never shies away from Arthur’s reluctance to change, as her healthy confronting topics such as gentrification, the alternatives food truck threatens to take away ong before the trends of grandes, mac- corporation creep into small neighborhoods some of the fresh clientele Franco and Arthur chiatos and pumpkin spice lattes, neigh- and the death of the small business owner. -

KEMS TV (Comcast Ch197, Digital Ch 36.2)

[ 12/26 ~ 1/1 ] KEMS TV (Comcast Ch197, Digital Ch 36.2) PROGRAM SCHEDULE changed programs KICU CH2 KOREAN TV Time 12/26 (Monday) 12/27 (Tuesday) 12/28 (Wednesday) 12/29 (Thursday) 12/30 (Friday) Time 12/31 (Saturday) 1/1 (Sunday) Time KBS New9 KBS New9 4 KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) 4 (Weekend Live) (Weekend Live) 4 40 40 Idol Battle Like Idol Battle Like 5 Hometown Report Hometown Report Hometown Report Hometown Report KBS Special 5 5 40 40 Mysteries of the Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Golden Oldies 6 First Love Again First Love Again First Love Again First Love Again First Love Again 6 Human Body 6 40 40 50 50 Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Sat & Sun Drama Sat & Sun Drama 20 The Gentlemen of The Gentlemen of 7 Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama 7 7 Still Loving You Still Loving You Still Loving You Still Loving You Still Loving You Wolgyesu Tailor Shop Wolgyesu Tailor Shop KBS New9 KBS New9 8 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 8 8 40 40 KEMS News Journal TV Kindergarten (E/I) 10 TV Kindergarten (E/I) Battle Trip 9 Morning Forum Morning Forum Morning Forum Morning Forum Morning Forum 9 9 40 10 10 Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Hello Counselor 10 10 10 First Love Again First Love Again First Love Again First Love Again First Love Again Music Bank 50 50 Hwarang: The 11 Invincible Youth 2 Open Concert Korea Sings -

Star Channels, September 23-29

SEPTEMBER 23-29, 2018 staradvertiser.com MAGNUM .0 2 Private investigator Thomas Magnum returns to TV screens on Monday, Sept. 24, when CBS doubles down on the reboot trend and reintroduces another fondly remembered franchise of yore with Magnum P.I. Jay Hernandez takes on the titular role in the reboot, while the character of Higgins is now female, played by Welsh actress Perdita Weeks. Premiering Monday, Sept. 24, on CBS. WE’RE LOOKING FOR PEOPLE WHO HAVE SOMETHING TO SAY. Are you passionate about an issue? An event? A cause? ¶ũe^eh\Zga^eirhn[^a^Zk][r^fihp^kbg`rhnpbmama^mkZbgbg`%^jnbif^gm olelo.org Zg]Zbkmbf^rhng^^]mh`^mlmZkm^]'Begin now at olelo.org. ON THE COVER | MAGNUM P.I. Back to the well ‘Magnum P.I.’ returns to the show was dropped in May. The person that the show wasn’t interested in being a 1:1 behind the controls is Peter M. Lenkov, a self- remake of its predecessor and was willing to television with CBS reboot professed fan of the ‘80s “Magnum” and a take big, potentially clumsy risks that could at- writer/producer on CBS’s first Hawaiian crime- tract the ire of diehard Magnum-heads. By Kenneth Andeel fest reboot, “Hawaii Five-0.” Lenkov’s secret Magnum’s second most essential posses- TV Media weapon for the pilot was director Justin Lin. Lin sion (after the mustache) was his red Ferrari, is best known for thrilling audiences with his and it turns out that that ride wasn’t so sacred, ame the most famous mustache to ever dynamic and outrageous action sequences in either. -

The Effects of Counselor Trainee Stress and Coping Resources on the Working Alliance and Supervisory Working Alliance

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Counseling and Psychological Services Department of Counseling and Psychological Dissertations Services 3-16-2010 The Effects of Counselor Trainee Stress and Coping Resources on the Working Alliance and Supervisory Working Alliance Philip B. Gnilka Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cps_diss Part of the Student Counseling and Personnel Services Commons Recommended Citation Gnilka, Philip B., "The Effects of Counselor Trainee Stress and Coping Resources on the Working Alliance and Supervisory Working Alliance." Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/cps_diss/48 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Counseling and Psychological Services at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Counseling and Psychological Services Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ACCEPTANCE This dissertation, THE EFFECTS OF COUNSELOR TRAINEE STRESS AND COPING RESOURCES ON THE WORKING ALLIANCE AND SUPERVISORY WORKING ALLIANCE, by PHILIP BRANSFORD GNILKA, was prepared under the direction of the candidate’s Dissertation Advisory Committee. It is accepted by the committee members in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in the College of Education, Georgia State University. The Dissertation Advisory Committee and the student’s Department Chair, as representatives of the faculty, certify that this dissertation has met all standards of excellence and scholarship as determined by the faculty. The Dean of the College of Education concurs. ______________________________ ________________________________ Catherine Y. Chang, Ph.D. -

![[ 6/5 ~ 6/11 ] KEMS TV (Comcast Ch197, Digital Ch 36.2) PROGRAM](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8229/6-5-6-11-kems-tv-comcast-ch197-digital-ch-36-2-program-3838229.webp)

[ 6/5 ~ 6/11 ] KEMS TV (Comcast Ch197, Digital Ch 36.2) PROGRAM

[ 6/5 ~ 6/11 ] KEMS TV (Comcast Ch197, Digital Ch 36.2) PROGRAM SCHEDULE changed programs KICU CH2 KOREAN TV Time 6/5 (Monday) 6/6 (Tuesday) 6/7 (Wednesday) 6/8 (Thursday) 6/9 (Friday) Time 6/10 (Saturday) 6/11 (Sunday) Time KBS New9 KBS New9 5 KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) KBS News 9 (Live) 5 (Weekend Live) (Weekend Live) 5 40 40 Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama The Mountain The Mountain Backpack Travels Golden Oldies Unknown Woman Unknown Woman Unknown Woman 6 6 6 575 576 25 26 27 40 40 532 1517 Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity 50 50 Sat & Sun Drama Sat & Sun Drama 7 20 Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama 20 7 My Father is Strange My Father is Strange 7 Still Loving You Still Loving You Lovers in Bloom Lovers in Bloom Lovers in Bloom 124 125 1 2 3 26 27 KBS New9 KBS New9 8 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 8 8 40 40 50 KEMS News Journal TV Kindergarten (E/I) 10 Battle Trip TV Kindergarten (E/I) 9 Morning Forum Morning Forum Morning Forum Morning Forum Morning Forum 9 9 40 51 10 Daily Drama Daily Drama Daily Drama 10 Hello Counselor K-rush K-rush 10 Unknown Woman Unknown Woman Unknown Woman 10 10 12 13 25 26 27 Music Bank 50 50 327 Entertainment The Return of Invincible Youth 2 Korea Sings The Return of 11 11 887 11 Weekly Superman Special 30 Immortal Songs 2 Superman Special 18 1851 1674 35 Backpack Travels 36 Wed & Thu Drama Mon &Tue Drama Mon &Tue Drama Wed & Thu Drama 10 12 Queen -

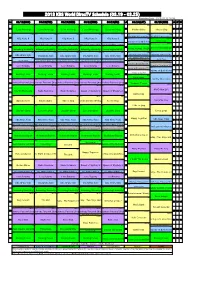

2018 KBS World Directv Schedule

2018 KBS World DirecTV Schedule (03.19 - 03.25) Reporting Date : 2018.03.12 16:36 LA 03/19(MON) 03/20(TUE) 03/21(WED) 03/22(THU) 03/23(FRI) LA 03/24(SAT) 03/25(SUN) LA SF NY 00 00 00 00 00 00 [®] 00 [®] 04 I Love Morinings I Love Morinings I Love Morinings I Love Morinings I Love Morinings 04 Golden Oldies I like to Sing 04 04 07 00 [L] 00 [L] 00 [L] 00 [L] 00 [L] 00 [L] 00 [L] KBS NEWS 9(Weekend Live) KBS NEWS 9(Weekend Live) 05 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 KBS News 9 05 30 [®] 30 [®][D] 05 05 08 Windows on Both Koreans The Mountain 00 00 00 00 [®] 00 00 [®][E] KBS WORLD News Today(R) KBS WORLD News Today(R) KBS WORLD News Today(R) KBS WORLD News Today(R) KBS WORLD News Today(R) 10 [®] 20 20 20 20 20 06 06 War For The Golden Seed06 06 09 Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity Screening Humanity History Journal, The Day 00 [®] 00 [®] 00 [®] 00 [®] 00 [®] 00 [®] 00 KBS NEWS 9(R) KBS News 9(Weekend R) KBS News 9(Weekend R) 07 KBS NEWS 9(R) KBS NEWS 9(R) KBS NEWS 9(R) KBS NEWS 9(R) 07 30 30 [®] 07 07 10 40 [®] KBS AMERICA NEWS 8(R) 50 50 50 50 The Beauty A Week Sisa K-Twon Sisa K-Twon KBS AMERICA NEWS 8(R) KBS AMERICA NEWS 8(R) KBS AMERICA NEWS 8(R) KBS AMERICA NEWS 8(R) 00 [®][E/I] Office Watch Season 2 10 [®][E] 10 [®][E] 10 [®][E] 10 [®][E] 10 [®][E]TV Kindergarten Kongdakong Y7-10(E/I)10 [®][E/I] 08 Love Returns Love Returns Love Returns Love Returns Love Returns 08 30 [®][E/I]TV Kindergarten Kongdakong Y7-10(E/I)08 08 11 40 50 [®] 50 [®] 50 [®] 50 [®] 50 [®]TV Kindergarten Kongdakong