Bozemangrowthpolicy-History.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Livingston Equestrian Ranch 39 Soaring Eagle Drive Livingston, Montana

Livingston Equestrian Ranch 39 Soaring Eagle Drive Livingston, Montana The Ranch Brokers | (307) 690-5425 | 610 S Hwy 93 | Hamilton, MT 59840 | www.theranchbrokers.com | [email protected] 1 LOCATION The Livingston Equestrian Ranch is located 4 miles northwest of Livingston, 35 miles east of Bozeman, 90 miles west of Billings, and 90 miles north of Yellowstone National Park. It has a view of three mountain ranges: the Absorkas to the Southeast, the Crazies to the East, and the Bridgers to the Northwest, all a part of the Rocky Mountains. The town of Livingston is one of the finest towns that Montana has to offer for western flair and country charm. Livingston has great dining, excellent shops and stores; it has several art galleries, historical buildings and several special events year round and is only 35 miles to the Bozeman Gallatin International Airport which has numerous flights from Delta, Big Sky, Frontier and many other airlines. Bozeman is home to Montana State University, rich with cultural events and several restaurants, stores, shopping plazas and keeping in tune with the Montana Flavor. The property is only 90 miles from the North Entrance of Yellowstone Park in Gardner, Montana. LOCALE Livingston is the original entrance to Yellowstone National Park, and it was here that rail passengers on the old Northern Pacific Railroad changed trains to catch the Park Branch Line to Yellowstone Park. Looking down Livingston’s Main Street, the historic, Western atmosphere of this frontier town remains intact in many of the city’s buildings. Over 436 buildings have been placed on the National Historic Register and walking maps are available at the Chamber of Commerce. -

Autobiography of Red Cloud War Leader of the Oglalas 1St Edition Pdf, Epub, Ebook

AUTOBIOGRAPHY OF RED CLOUD WAR LEADER OF THE OGLALAS 1ST EDITION PDF, EPUB, EBOOK R Eli Paul | 9780917298509 | | | | | Autobiography of Red Cloud War Leader of the Oglalas 1st edition PDF Book Told by the Gros Ventres of the near proximity of the Sioux, the Ree villagers had set up an ambush. Stock photo. Allen wrote them out in his own decorous prose and in the third person, rather than the autobiographical first. Here, for the first time in print is Red Cloud's 'as-told-to' autobiography in which he shares the story of his early years. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Charles Wesley Allen ,. Average rating 3. There was great rejoicing when he entered his own village, for it was supposed that he had been killed. Just a moment while we sign you in to your Goodreads account. Most of Red Cloud's story has been published 'third hand'. About this product. He is best known for his success in confrontations with the U. When he was around 5 years old, Red Cloud lost his father. Ben rated it really liked it Apr 10, Red Cloud's autobiography is just a glimmer, it's just so so so bittersweet. At the foot of that mountain is our village; there is where the women are. The Sioux had decided to make a rush and stampede the herd and, if an opportunity presented itself, shoot a struggling Ree or two and escape with their booty. Be the first to ask a question about Autobiography of Red Cloud. Paperback and kindle versions are available for purchase on amazon. -

Horse Thief Trail Ranch 680 Acres with a Log Home and Barn - Livingston, MT!

Horse Thief Trail Ranch 680 Acres with a Log Home and Barn - Livingston, MT! The Ranch Brokers | (307) 690-5425 | 610 S Hwy 93 | Hamilton, MT 59840 | www.theranchbrokers.com | [email protected] 1 LOCATION Located just 10 miles north of Livingston, Montana and 45 miles from Bozeman, Montana. Air Service Available: Gallatin Field Airport services several major airlines including Alaska, Allegiant, Delta, Frontier, Horizon, United and US Airways. For convenience, it offers many direct flights to Seattle/Tacoma, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Salt Lake City, Denver, Phoenix, Minneapolis, Chicago and Atlanta, making it easily accessible from all over the country. LOCALE The general area is nearly surrounded by public land with over 970,000 acres of wilderness and nearly 2,000,000 acres of National Forest land with approximately 3,000,000 acres of Yellowstone National Park nearby. Access to a trail network extending for hundreds of miles in all directions for wildlife photography, hiking or horseback riding is just minutes away. Livingston, with a population of approximately 7,500, is just 7 miles away and supplies most major shopping needs with supermarkets, auto dealerships, equipment suppliers, retail stores, and hospital. Bozeman, has a population of 30,000, approximately 26 miles away, offers excellent commercial airline connections and is home to Montana State University. It is the cultural center of South-central Montana. HISTORY OF AREA Park County is the original gateway to Yellowstone National Park. The Yellowstone River flows south to north through the county - turning east at Livingston. The county is rich with history and legend. -

The Erosion of the Racial Frontier: Settler Colonialism and the History

THE EROSION OF THE RACIAL FRONTIER: SETTLER COLONIALISM AND THE HISTORY OF BLACK MONTANA, 1880-1930 by Anthony William Wood A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana April 2018 ©COPYRIGHT by Anthony William Wood 2018 All Rights Reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the history faculty at Carroll College and Dr. Swarthout who pushed history majors such as myself to work as interns with the Montana State Historic Preservation Office in Helena, Montana. It was at SHPO that I was so fortunate to work for Kate Hampton, who had already worked tirelessly keeping the Montana’s African American Heritage Places Project alive for over a decade, and who continued to lead and guide me while I researched and wrote for the project for three years. Classes I took at MSU, especially Dr. Mark Fiege’s seminar on the American West, offered strikingly new approaches that opened up different methods as well as mountains of scholarship that would profoundly inform how I thought about race and the American West. I am further indebted to my wonderful committee members, Drs. Mary Murphey, Amanda Hendrix- Komoto, Billy Smith, and my chair, Mark Fiege for all their time spent talking with me about sections of my thesis, different approaches I might try, or even just listening as I tried to organize my ideas. I am also thankful and sorry to my office-mates Amanda Hardin and Jen Dunn who were unlucky enough to work within ear-shot. -

Section 3 Northeast Area Including Sheridan, Buffalo, Dayton, Gillette, and Newcastle

SECTION 3 NORTHEAST AREA INCLUDING SHERIDAN, BUFFALO, DAYTON, GILLETTE, AND NEWCASTLE 184 wagons, a contingent of Pawnee scouts, nearly 500 cavalrymen, and the aging Jim Bridger as guide. His column was one of three comprising the Powder River Indian Expedition sent to secure the Bozeman and other emigrant trails leading to the Montana mining fields. During the Battle of Tongue River, Connor was able to inflict serious damage on the Arapahos, but an aggressive counter attack forced him to retreat back to the newly estab- lished Fort Connor (later renamed Reno) on the banks of the Powder River. There he received word that he had been reassigned to his old command in the District of Utah. The Powder River Expedition, one of the most comprehensive campaigns against the Plains Indians, never completely succeeded. Connor had planned a complex operation only to be defeated by bad weather, inhospitable ter- Section 3 rain, and hostile Indians. Long term effects of the Expedition proved detrimental to the inter- ests of the Powder River tribes. The Army, with the establishment of Fort Connor (Reno) increased public awareness of this area which Devils Tower near Sundance. in turn caused more emigrants to use the Bozeman Trail. This led to public demand for government protection of travelers on their way 1 Food, Lodging T Connor Battlefield State to Montana gold fields. Historic Site Ranchester In Ranchester Pop. 701, Elev. 3,775 Once the site of a bloody battle when General Named by English born senator, D.H. Hardin, Patrick E. Connor’s army attacked and destroyed Ranchester was the site of two significant battles Arapahoe Chief Black Bear’s settlement of 250 during the Plains Indian Wars. -

National Register of Historic Places Inventory « Nomination Form

ormNo. 10-300 ^e^', AO-"1 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES INVENTORY « NOMINATION FORM SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES -- COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS_________ [NAME HISTORIC _____Yellowstone Crossing, Bozeman Trail___________________________ AND/OR COMMON ______Yellowstone Crossing , Bozeman Trail_________________________ LOCATION SEi/4SWi/4/ SW1/4SE1/4 Sec. 1, NE1/4NW1/4, N1/2NE1/4 Sec. 18, STREET&NUMBER T.1S., R.13E. —NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Springdale JL VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Morrhana 030 Sweetarass 097^ CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE D I STRICT —PUBLIC —OCCUPIED ^.AGRICULTUREX —MUSEUM BUILDING(S) —JpRIVATE —^UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK STRUCTURE —BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT _IN PROCESS J^YES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER: OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME ____Arche Marcotte / Mrs. Elizabeth Wood Marcotte (wife) STREET & NUMBER 511 Sixth Avenue CITY. TOWN STATE Havre VICINITY OF Montana i LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS/ETC. Sweetqrass County Courthouse STREET & NUMBER CITY, TOWN STATE Mnrrhana I REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE Montana Historic Sites Inventory: Robert A. Murray DATE September r 1Q68 —FEDERAL _^JSTATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR Recreation & Parks Divsion, Department of Fish and Game SURVEY RECORDS 1420 East Sixth_____________________________________ CITY. TOWN STATE Montana DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE _EXCELLENT _DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS ALTERED _MOVED DATE——————— .XFAIR __UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE The Yellowstone Crossing of the Bozeman Trail lies 21 miles east of Livingston and 12 miles west of Big Timber. -

Army Historical Series

ARMY HISTORICAL SERIES ARMY HISTORICAL SERIES AMERICAN MILITARY HISTORY CENTER OF MILITARY HISTORY UNITED STATES ARMY WASHINGTON, DC 1989 (This CMH Online version of American Military History is published without the photographs. The maps have been inserted into the text at a reduced size to speed loading of the documents. To view the maps at their full-resolution, double-click the image in the text.) Contents http://www.army.mil/cmh-pg/books/AMH/amh-toc.htm (1 of 3) [2/20/2001 11:24:24 AM] ARMY HISTORICAL SERIES Chapter Page FRONT MATTER v 1 Introduction 1 2 The Beginnings 18 3 The American Revolution: First Phase 41 4 The Winning of Independence, 1777-1783 70 5 The Formative Years, 1783-1812 101 6 The War of 1812 122 7 The Thirty Years’ Peace 148 8 The Mexican War and After 163 9 The Civil War, 1861 184 10 The Civil War, 1862 209 11 The Civil War, 1863 236 12 The Civil War, 1864-1865 262 13 Darkness and Light: The Interwar Years, 1865-1898 281 14 Winning the West: The Army in the Indian Wars, 1865-1890 300 15 Emergence to World Power, 1898-1902 319 16 Transition and Change, 1902-1917 343 17 World War I: The First Three Years 358 http://www.army.mil/cmh-pg/books/AMH/amh-toc.htm (2 of 3) [2/20/2001 11:24:24 AM] ARMY HISTORICAL SERIES 18 World War I: The U.S. Army Overseas 381 19 Between World Wars 405 20 World War II: The Defensive Phase 423 21 Grand Strategy and the Washington High Command 446 22 World War II: The War Against Germany and Italy 473 23 World War II: The War Against Japan 499 24 Peace Becomes Cold War, 1945-1950 529 25 The Korean War, 1950-1953 545 26 The Army and the New Look 572 27 Global Pressures and the Flexible Response 591 28 The U.S. -

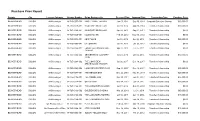

Purchase Price Report

Purchase Price Report County City License Category License Number Doing Business As Received Date Approval Date Transaction Type Purchase Price BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0007-002 KNOTTY PINE TAVERN Jun 03, 2011 Sep 06, 2011 Corporate Structure Change $90,000.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0020-001 KLONDIKE INN DILLON Jul 09, 2014 Aug 20, 2014 Transfer of Ownership $30,000.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0020-001 KLONDIKE INN DILLON Apr 29, 2013 Aug 01, 2013 Transfer of Ownership $0.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0020-001 KLONDIKE INN Feb 29, 2012 May 30, 2012 Transfer of Ownership $0.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0038-001 KB'S PLACE Jul 12, 2012 Oct 29, 2012 Transfer of Ownership $25,000.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0059-001 DILLON BAR Jul 27, 2012 Jan 30, 2013 Transfer of Ownership $0.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0064-001 FRONTIER CONVENTION Apr 22, 2011 Jul 25, 2012 Transfer of Ownership $0.00 CENTER BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0064-002 BEAVERHEAD COUNTRY Jul 23, 2012 Oct 02, 2012 Transfer of Ownership $30,000.00 CLUB BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0083-002 THE LION'S DEN Jul 06, 2017 Dec 19, 2017 Transfer of Ownership $0.00 STEAKHOUSE AND BAR BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0083-002 LIONS DEN SUPPER CLUB Sep 14, 2017 Dec 12, 2017 Transfer of Ownership $30,000.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0088-001 THE METLEN BAR Dec 22, 2010 May 04, 2011 Transfer of Ownership $20,000.00 BEAVERHEAD DILLON All-Beverages 18-725-0105-002 -

A Tabloid History of Montana

ATabloidHistoryofMontana by Bob Fletcher This Tabloid History of Montana or "The Pioneer History of the Land of Shining Mountains" appeared on the reverse side of a historical map published by the Montana Highway Commission in 1937. Scientists tell a fascinating tale of prehistoric Montana in which these erudite gentlemen toss offmillions of years in the nonchalant manner of a Congressman speaking of a billion dollar appropriation. Such figures are just too large for our average five-and-ten minds to grasp. In the dim and distant past most of Montana's framework was built under water in horizontal layers of sedimentary rocks. Later a portion was lifted and formed the shore line and coastal plain of a shallow marshy arm of the great sea which covered America from the Gulf of Mexico to the Arctic Ocean. The climate was the sort that Florida real estate men brag about. Sashaying through the tropical vegetation were the mean looking reptiles we call dinosaurs. Now fossil hunters find their skeletons sealed in the rocks that formed the prehistoric mud and ooze. Next Dame Nature developed a gigantic stomach ache in western Montana that caused her erstwhile placid countenance to crease with anguish. The largest wrinkles are the mountain ranges, the troughs between are structural valleys. The corrugations broadened and tapered offacross eastern Montana into gently sloping anticlines. Hell boiled over in the west. Restless molten masses beneath the sedimentaries bulged and fractured them; volcanic ash deluged the valleys, and lava sheets flowed down the mountain sides. Central Montana broke out in a rash. -

When Whales Walked

Program Guide KENW-TV/FM Eastern New Mexico University Q2 3 June 2019 WHEN WHALES WALKED: JOURNEYS IN DEEP TIME AN EPIC TALE OF EVOLUTION When to watch from A to Z listings for 3-1 are on pages 18 & 19 Channel 3-2 – June 2019 PBS NewsHour – Weekdays, 6:00 p.m./12:00 midnight Amanpour and Company – Tuesdays–Thursdays, 11:00 p.m. Quilt in a Day – Saturdays, 12:30 p.m. America’s Heartland – Saturdays, 6:30 p.m. Quilting Arts – Saturdays, 1:00 p.m.; Wednesdays, 12:30 p.m. America’s Test Kitchen – Saturdays, 7:30 a.m.; Thursdays, 11:30 a.m. Red Green Show – Thursdays, 9:30 p.m. (except 6th); Antiques Roadshow – Mondays, 7:00 p.m./8:00 p.m. (except 3rd); Saturdays, 8:30 p.m. (except 1st, 8th) Mondays, 11:00 p.m. (11:30 p.m. on 17th); Sundays, 7:00 a.m. Report from Santa Fe – Saturdays, 6:00 p.m. Ask This Old House – Saturdays, 4:00 p.m. (except 8th) Second Opinion – Wednesdays, 10:00 p.m. (except 5th); Austin City Limits – Sundays, 6:30 a.m./3:30 p.m. (except 9th, 16th) Saturdays, 9:00 p.m. (except 1st, 8th)/12:00 midnight Sewing with Nancy – Saturdays, 5:00 p.m. BBC Newsnight – Fridays, 5:00 p.m. Sit and Be Fit – Mondays/Wednesdays/Fridays, 12:00 noon BBC World News – Weekdays, 6:30 a.m./4:30 p.m. Song of the Mountains – Thursdays, 8:00 p.m. (except 6th) Beads, Baubles and Jewels – Mondays, 12:30 p.m. -

Canyon Echoesechos

National Park Service Park News U.S. Department of the Interior CanyonCanyon EchoesEchos Your Guide to Bighorn Canyon 2011 Kleine Photo Collection What’s Inside Welcome to Bighorn Canyon Concession Services .................... 2 Welcome to Bighorn Canyon, the park staff invites you Highlights of things to come at Bighorn Canyon Boating and PWC Regulations .... 2 to enjoy the recreation area and participate in activities includes installation of web cameras at both Ok-A- Pack it in, Pack it out, Recycle ...... 2 offered here to make your visit more enjoyable. New Beh and Horseshoe Bend Marinas. This will allow Hiking ......................................... 3 program opportunities will be offered as a way for you for a real time look at activities, conditions on the You Need To Know....................... 3 to enjoy America’s Great Outdoors. launch ramp, current weather conditions, and status of Be Safe ....................................... 4 parking. Wildlife Watching ....................... 4 If you’ve picked this paper up at one of our visitor Camping ..................................... 4 centers you’re well on your way to exploring this This is your park to preserve and enjoy in America’s amazing park! Great Outdoors! Fees .............................................. 5 Field School ................................ 5 The interpretive division of Bighorn Canyon NRA has Activities .................................... 6 been busy creating new programs and introducing new Mountain Men ........................... 6 faces. One of the most exciting new opportunities will Junior Ranger Program ................ 7 be the chance to explore the inner reaches of Bighorn Bozeman Trail .............................. 7 Canyon on Ranger led boat tour provided by Hidden Map ............................................. 8 Treasures Charters, a park concessionaire. This tour offers breath taking views of sculpted canyon walls; don’t forget to bring your camera! Visit page 2 in this Summer paper for information on scheduling a tour. -

Section 5 I Southcentral Area Ncluding Including Casper, Riverton, Lander and Rawlins

SECTION 5 I SOUTHCENTRAL AREA NCLUDING INCLUDING CASPER, RIVERTON, LANDER AND RAWLINS post provided a link between East and West in C communications and supply transport. The Post ASPER at Platte Bridge, also known as Fort Clay, Camp S OUTHCENTRAL Davis, and Camp Payne, was associated with two , R significant military campaigns, the Sioux Expedition of 1855-1856 and the Utah IVERTON Expedition of 1858-1859. Furthermore, the mili- tary camp played an important role in Indian- Euro-American relations. , L A The post at Platte Bridge protected the most ANDER AND REA important river crossing in Wyoming, in the most hostile area of Wyoming, aiding in travel and communication on the Oregon Trail. Undoubtedly, the camp also played a significant role in relations between Plains Indian tribes and R the U S. Army as the post acted out it’s role as AWLINS peacekeeper, protector, and aggressor.” Memorial Cemetery and Mausoleum This site is located lust north of the Evansville Elementary School near the corner of 5th and Albany Streets on a tract of land known as the “Oregon Trail Memorial Park.” This is the burial tomb of six skeletons recovered from an unmarked cemetery believed to be circa 1850s. Research indicated that the initial remains consist- ed of four males and two females. Later three North of Rawlins skeletons, believed to be Native Americans, were included in the interment. Five of the skeletons, and Cheyenne hunted the buffalo. In addition is Food including one of the females, were clothed in mili- 1 the location of the “Mysterious Cross.” tary uniform, parts of which were recovered with Section 5 military buttons and insignia attached.