Revisiting the Viqueque Rebellion of 1959

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Timor-Leste Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor

Timor-Leste Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor (BACET) Cooperative Agreement 486-A-00-06-00011-00 Quarterly Report July 01 - September 30, 2010 Submitted to: USAID/Timor-Leste Dili, Timor-Leste Angela Rodrigues Lopes da Cruz, Agreement Officer Technical Representative Submitted by: Land O’Lakes, Inc. International Development Division P. O. Box 64281 St. Paul, MN 55164-0281 U.S.A. October 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Land O'Lakes, Inc. All rights reserved. Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor CA # 486-A-00-06-00011-00 BUILDING AGRIBUSINESS CAPACITY IN EAST TIMOR USAID CA# 486-A-00-06-00011-00 Quarterly Report July - September 2010 Name of Project: Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor Locations: Fuiloro, Lautem District Maliana, Bobonaro District Natarbora, Manatutu District Dates of project: September 22, 2006 – September 30, 2011 Total estimated federal funding: $6,000,000 Total federal funding obligated: $6,000,000 Total project funds spent to September 30, 2010: $5,150,425 Contact in Timor-Leste: Michael J. Parr, Chief of Party Telephone: +670 331-2719 Mobile: +670 735-4382 E-mail: [email protected] Summary: BACET directly contributes to USAID/Timor- Leste’s agriculture and workforce development strategies for economic growth. though categorized as a capacity building and workforce development activity, many of the key activities of BACET have included infrastructure improvements, which are longer-term in nature. Similarly, teacher training and changed teaching methods have long-term impact. Quarterly Report July - September 2010 Land O'Lakes, Inc. Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor CA # 486-A-00-06-00011-00 Table of Contents 1. -

Development and Its Discontents: the Indonesian Government, Indonesian Opposition, and the Occupation of East Timor

Development and its Discontents: The Indonesian Government, Indonesian Opposition, and the Occupation of East Timor M. Scott Selders Based on a section of M. Scott Selders, “Patterns of Violence: Narratives of Occupied East Timor from Invasion to Independence, 1975-1999” (MA thesis, Concordia University, 2008). IAGS 9th Biennial Conference, Buenos Aires, July 2011 In 1974, decolonization began in Portugal’s colony of East Timor.1 In December 1975, this process was curtailed by neighboring Indonesia’s invasion, after which President Suharto’s New Order regime imposed a brutal occupation lasting until 1999. Between 1974 and 1999, it is estimated that over 100,000, and possibly as many as 183,000, East Timorese perished.2 The Indonesian government justified the invasion by reminding its Western allies of the Suharto regime’s staunch anti-Communism and by arguing that East Timor’s small size, poverty, and underdevelopment meant it was not a viable independent country.3 Consequently, after 1975, one of Indonesia’s main justifications for the occupation was that it was balancing the neglect of the Portuguese colonial administration by modernizing East Timor and the Timorese. This paper examines a sample of this development rhetoric from the 1980s. It also shows that such rhetoric was not universally accepted, even within Indonesia, as evidenced by two Indonesian sources from the early 1990s that directly question and contradict the Indonesian government’s civilizing claims. The Indonesian provenance of these 1 Standard surveys include Jill Jolliffe, East Timor: Nationalism and Colonialism (St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1978); John G. Taylor, Indonesia’s Forgotten War: The Hidden History of East Timor (London: Zed Books, 1991); James Dunn, Timor: A People Betrayed (Sydney: ABC Books, 1996); Arnold S. -

AUSTRALIAN and INDONESIAN NEWS COVERAGE of the Dili MASSACRE

AUSTRALIAN AND INDONESIAN NEWS COVERAGE OF THE DILi MASSACRE ( A Content Analysis of Australian and Indonesian Newspapers from 1 July 1991 to 31 March 1992) ' Yuventius Agustinus Nunung Prajarto A thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts SCHOOL OF POLITICAL SCIENCE FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES UNIVERSITY OF NEW SOUTH WALES SYDNEY - AUSTRALIA 1994 iv AUSTRALIAlf ARD IImOHBSIAN IIEWS COVERAGE OP TBB DILI IIASSACRB (A content Analysis of Australian and Indonesian Newspapers frOII 1 July 1991 to 31 Karch 1992) SCHOOL OP POLITICAL SCIENCE FACULTY OP AR'l' ARD SOCIAL SCIENCES THE UNIVERSITY OP REif SOUTH WALES 1994 V AUSTRALIAN AIID IRDONBSIAN NEWS COVERAGE OF TIIB DILI MASSACRE (A Content Analysis of Australian and Indonesian Newspapers fr0111 July 1991 to 31 Karch 1992) Yuventius Agustinus Hunung Prajarto Thesis POLITICAL SCIENCE 1994 STATEMENT Name : Yuventius Agustinus Nunung Prajarto student No.: 2114322 School of Political science Faculty of Arts and social Sciences University of New south Wales I hereby declare that this submission is my own work and that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, it contains no material previously published or written by another person nor material which to a substantial extent has been accepted for the award of any other degree or diploma of a university or other institute of higher learning, except where due acknowledgement is made in the text. Date : 8 Febr~y 1994 Signatu ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS There are a number of people whom I can thank by name. I am particularly grateful to Rodney Smith, my supervisor. His help was invaluable in guiding the process of this research till its finishing touch. -

Dili Massacre and How It Backfired, I Popular Support

Brian Martin, Justice Ignited, chapter 3 (author’s prepublication version) 3 Dili On 12 November 1991, Indonesian troops colonies — such as Angola and Mozambique gunned down hundreds of peaceful protesters — to gain independence. in Dili, the capital of East Timor. This act was In East Timor, Portugal’s most remote intended to intimidate opponents of Indonesian colony, with a population of nearly 700,000, rule. But instead, the killings triggered a huge rival political forces struggled for supremacy increase in international support for East in the transition from Portuguese rule, with the Timor’s independence. In order to understand liberation movement Fretilin having most the Dili massacre and how it backfired, I popular support. In December 1975, Indone- review its background and aftermath, giving sian military forces invaded and occupied East special attention to the five methods attackers Timor. According to some commentators, the use to inhibit outrage. Indonesian government had obtained agree- Most of the archipelago today called ment for the operation from the Australian and Indonesia was previously a colony of the U.S. governments.2 Fretilin fought the inva- Netherlands. Indonesia obtained its independ- sion but soon retreated to the mountains where ence in 1949. The new government, led by it maintained a guerrilla resistance to the Sukarno, fostered a strong sense of national- Indonesian occupiers. ism. In 1965, there was a military coup, The invasion and occupation were bloody, accompanied by a massive anticommunist with many fighters and civilians killed. purge, with hundreds of thousands of people Indonesian forces perpetrated serious human killed.1 The new regime, led by General rights violations, including torture, rape, and Suharto, was ideologically procapitalist, but it killing of civilians; Fretilin did the same, retained its predecessor’s strong nationalism. -

53395-001: Water Supply and Sanitation Investment Project

Initial Environmental Examination March 2021 Timor-Leste: Water Supply and Sanitation Investment Project – Viqueque City Subproject (Part 1 of 5) Prepared by the Directorate General for Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Public Works for the Asian Development Bank. (page left Intentionally blank) i ABBREVIATIONS WSSIP - Water Supply and Sanitation Investment Project ACMs - Asbestos Containing Materials ADB - Asian Development Bank DED - Detailed Engineering Design DGAS - Directorate General for Water and Sanitation DNAP - National Directorate for Protected Areas DNCP - National Directorate for Pollution Control DNSA - National Directorate for Water Services EARF - Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EHS - Environment, Health and Safety EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EIS - Environmental Impact Statement EMP - Environmental Management Plan EMR - Environmental Monitoring Report ESS - Environmental Safeguard Specialist ESA - Environmental Safeguard Assistant FSTP - Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IFC - International Finance Corporation MPW - Ministry of Public Works PA - Protected Area PD - Project Document PDC - Project Design Consultant PSC - Project Supervision Consultant PMU - Project Management Unit SEA - Superior Environmental Authority SEIS - Simplified Environmental Impact Statement CEMP - Site-specific Construction EMP SMASA - Municipal Water, Sanitation and Environment Services SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TOR - Terms of Reference WDZ - Water -

Fieldwork in Timor-Leste

Understanding Timor-Leste, on the ground and from afar (eds) and Bexley Nygaard-Christensen This ground-breaking exploration of research in Timor-Leste brings together veteran and early-career scholars who broadly Fieldwork in represent a range of fieldwork practices and challenges from colonial times to the present day. Here, they introduce readers to their experiences of conducting anthropological, historical and archival fieldwork in this new nation. The volume further Timor-Leste explores the contestations and deliberations that have been in Timor-Leste Fieldwork symptomatic of the country’s nation-building process, high- Understanding Social Change through Practice lighting how the preconceptions of development workers and researchers might be challenged on the ground. By making more explicable the processes of social and political change in Timor- Leste, the volume offers a critical contribution for those in the academic, policy and development communities working there. This is a must-have volume for scholars, other fieldworkers and policy-makers preparing to work in Timor-Leste, invaluable for those needing to understand the country from afar, and a fascinating read for anyone interested in the Timorese world. ‘Researchers and policymakers reading up on Timor Leste before heading to the field will find this handbook valuable. It is littered with captivating fieldwork stories. The heart-searching is at times searingly honest. Best of all, the book beautifully bridges the sometimes painful gap between Timorese researchers and foreign experts (who can be irritating know-alls). Academic anthropologists and historians will find much of value here, but the Timor policy community should appreciate it as well.’ – Gerry van Klinken, KITLV ‘This book is well worth reading by academics, activists and policy-makers in Timor-Leste and also those interested in the country’s development. -

2018 Timor-Leste Study Tour Report

1 Table of Contents About the Tour ...................................................................................................................... 4 Timor-Leste Overview .......................................................................................................... 6 History ................................................................................................................................. 7 Politics ............................................................................................................................... 10 The Economy .................................................................................................................... 13 Society and Culture……………………………………………………………………………16 Health and Education ....................................................................................................... 17 Australia-Timor Relations .................................................................................................. 21 Appendixes .......................................................................................................................... 23 i) Participants……………………………………………………………………………………23 ii) Participant Reflections ................................................................................................... 24 iii) Study Tour Itinerary with Map ...................................................................................... 28 Bibliography ....................................................................................................................... -

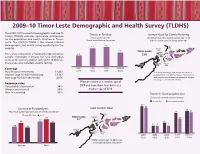

Timor-Leste DHS 2009-10 Fact Sheet

2009–10 Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Survey (TLDHS) The 2009–10 Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Trends in Fertility Unmet Need for Family Planning Survey (TLDHS) provides up-to-date information TFR for women for the Percent of currently married women age 15-49 on the population and health situation in Timor- 3-year period before the survey with an unmet need for family planning* Leste. The 2009–10 TLDHS is the second national demographic and health survey conducted in the 7.4 7.8 Dili 29% country. Liquiçá Lautem 5.7 Timor-Leste 29% Baucau 28% Aileu Manatuto 35% 27% The survey is based on a nationally representative 4.4 31% Ermera 30% Viqueque sample. It provides estimates for rural and urban 23% 31% Bobonaro Manufahi areas of the country and for each of the 13 districts. 42% 22% The survey also included anemia testing. Oecussi Covalima Ainaro 40% 17% 43% Coverage 1997 2002 2003 2009-10 IDHS MICS DHS TLDHS Households interviewed 11,463 *Currently married fecund women who want to Women (age 15–49) interviewed 13,137 postpone their next birth for two or more years or Men (age 15–54) interviewed 4,076 who want to stop childbearing altogether but are not using a contraceptive method Women marry at a median age of Response rates Households interviewed 98% 20.9 and have their first birth at a Women interviewed 95% median age of 22.4. Men interviewed 92% Trends in Contraceptive Use Percent of currently married women Any method Any modern method 27 25 Literacy of Respondents Total Fertility Rate 22 21 Percent of women and men age 15-49 -

Massacre Timorese

Timor link, no. 22, February 1992 This is the Published version of the following publication UNSPECIFIED (1992) Timor link, no. 22, February 1992. Timor link (22). pp. 1-8. The publisher’s official version can be found at Note that access to this version may require subscription. Downloaded from VU Research Repository https://vuir.vu.edu.au/25957/ Number 22 February 1992 Massacre highlights Timorese plight East Timor became world news in November when Indonesian troops fired on a funeral procession at the Santa Cruz cemetery, Dill, the territory's capital, killing up to 200 people. The incident tragically highlighted an injustice long ignored by much of the international community. The massacre followed a period of mounting tension in the former Portuguese colony, illegally occupied by Indonesia since 1975, with reports pointing to an escalating campaign of York radio station WBAI were in East Timor 'I turned around - tremendous amount Indonesian repression in the run-up to to report on alleged human rights abuses, of gun fire -- and there were dozens of a planned delegation of Portuguese and were badly beaten by troops while the people lying in the streets. ' parliamentarians in November. The shooting was going on. Bob Muntz, South East Asia project officer delegation was called off on 24 October According to Nairn: 'It was ... a planned with Australia's Community Aid Abroad, after Portuguese concern at Indonesia's and systematic massacre .... This was not a was also present and managed to escape. attempts to control and manipulate the situation where you had some hothead who On return to Melbourne he told a press visit. -

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’S Office (RCO) Situation Report No

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) Situation Report No. 6 (As of 21 April 2021) This report is produced by RCO Timor-Leste in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It is issued by UN Timor-Leste. It covers the period from 16 to 21 April 2021. The next report will be issued on or around 28 April 2021. HIGHLIGHTS • Following the Government’s declaration of a state of calamity in Dili on 8 April, several humanitarian donors have provided additional humanitarian support the flood response, equivalent to nearly USD 10 million. • According to the latest official figures (21 April) from the Ministry of State Administration, which leads the Task Force for Civil Protection and Natural Disaster Management, a total of 28,734 households have reportedly been affected by the floods across all 13 municipalities. Of whom, 90% - or 25,881 households – are in Dili municipality. • The same report cites that currently there are 6,029 temporary displaced persons in 30 evacuation facilities across Dili, the worst-affected municipality. • 4,546 houses across all municipalities have reportedly been destroyed or damaged. • According to the preliminary assessment by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries conducted in 9 municipalities to date, a total of 1,820 ha of rice crops and 190 ha of maize crops have been affected by the flooding. 13 28,734 4,546 30 41 Municipalities Total affected Houses Evacuation Fatalities affected (out households destroyed or facilities in of 13 across the damaged across Dili municipalities) country the country SITUATION OVERVIEW Heavy rains across the country from 29 March to 4 April have resulted in flash floods and landslides affecting all 13 municipalities in Timor-Leste to varying degrees, with the capital Dili and the surrounding low-lying areas the worst affected. -

The Study on Urgent Improvement Project for Water Supply System in East Timor

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EAST TIMOR TRANSITIONAL ADMINISTRATION THE STUDY ON URGENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM IN EAST TIMOR FINAL REPORT VolumeⅠ: SUMMARY REPORT FEBRUARY 2001 TOKYO ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS, CO., LTD. PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL SSS JR 01-040 THE STUDY ON URGENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM IN EAST TIMOR FINAL REPORT CONSTITUENT VOLUMES VOLUME Ⅰ SUMMARY REPORT VOLUME Ⅱ MAIN REPORT VOLUME Ⅲ APPENDIX VOLUME Ⅳ QUICK PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION MANUAL Foreign Exchange Rate: USD 1.00 = INDONESIA RUPIAH 9,500 AUD 1.00 = JPY 58.50 USD 1.00 = JPY 111.07 (Status as of the 30 November 2000) PREFACE In response to a request from the United Nations Transitional Administration of East Timor, the Government of Japan decided to conduct The Study on Urgent Improvement Project for Water Supply System in East Timor and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team headed by Mr. Kazufumi Momose of Tokyo Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. in association with Pacific Consultants International to East Timor, twice between February 2000 and February 2001. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the East Timor Transitional Administration and Asian Development Bank which is a trustee of East Timor Trust Fund and conducted field surveys in the study area. Based on the field surveys, the Study Team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of this project and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between Japan and East Timor Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the East Timor Transitional Administration for their close cooperation extended to the Study. -

Analytical Report on Education Timor-Leste Population and Housing Census 2015

Census 2015 Analytical Report on Education Timor-Leste Population and Housing Census 2015 Thematic Report Volume 11 Education Monograph 2017 Copyright © GDS, UNICEF and UNFPA 2017 Copyright © Photos: Bernardino Soares General Directorate of Statistics (GDS) United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) 1 Executive Summary Education matters. It is the way through which one generation passes on its knowledge, experience and cultural legacy to the next generation. Education has the means to empower individuals and impacts every aspect of life. It is the vehicle to how one develops and understands the world. It creates opportunities for decent work and higher income and is correlated to many other components which can enrich one's quality of life and contribute to happiness, health, mental well-being, civic engagement, home ownership and long-term financial stability. Besides the economic implications, education is a fundamental right of each and every child. It is a matter of fulfilling basic human dignity, believing in the potential of every person and enhancing it with knowledge, learning and skills to construct the cornerstones of healthy human development (Education Matters, 2014)1. It is important to consider those most vulnerable and deprived of learning and ensure they receive the access to education they deserve. Simply stated: all children form an integral part of a country's future and therefore all should be educated. To protect the right of every child to an education, it is crucial to focus on the following components2: a) early learning in pre-schools, b) equal access to education for all children, c) guarantee education for children in conflict or disaster-prone areas and emergencies, d) enhance the quality of the schools, e) create partnerships to ensure funding and support and f) Build a strong education system.