2018 Timor-Leste Study Tour Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

East Timor Law and Justice Bulletin (ETLJB), the Principal International NGO That Runs an HIV-AIDS Transmission Reduction Program Excludes Gays from Its Program

TIMOR-LESTE Timor-Leste is a multiparty parliamentary republic with a population of approximately 1.1 million. President Jose Ramos-Horta was head of state. Prime Minister Kay Rala Xanana Gusmao headed a four-party coalition government formed following free and fair elections in 2007. International security forces in the country included the UN Police (UNPOL) within the UN Integrated Mission in Timor-Leste (UNMIT) and the International Stabilization Force (ISF), neither of which was under the direct control of the government. The national security forces are the National Police (PNTL) and Defense Forces (F-FDTL). Security forces reported to civilian authorities, but there were some problems with discipline and accountability. Serious human rights problems included police use of excessive force during arrest and abuse of authority; perception of impunity; arbitrary arrest and detention; and an inefficient and understaffed judiciary that deprived citizens of due process and an expeditious and fair trial. Domestic violence, rape, and sexual abuse were also problems. RESPECT FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Section 1 Respect for the Integrity of the Person, Including Freedom From: a. Arbitrary or Unlawful Deprivation of Life There were no politically motivated killings by the government or its agents during the year; however, on August 27, F-FDTL soldiers were involved in a fight with locals in Laivai, Lautem, in which one civilian was beaten to death. The case was handed to the Prosecutor General's Office and the Human Rights Ombudsman for investigation. At year's end the investigation was ongoing. There were no developments in the May 2009 case in which a group of F-FDTL members allegedly beat two men on a beach in Dili; one of the victims was subsequently found dead. -

Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of COVID-19 in Timor-Leste

Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of COVID-19 in Timor-Leste United Nations Timor-Leste 2020 with technical lead from UNDP Socio-economic impact assessment of COVID-19 in Timor-Leste Research Team Dolgion Aldar (UNDP SEIA and Livelihoods Consultant), Noelle Poulson (UNDP MSME Consultant), Ricardo Santos (UNDP Social Protection Consultant), Frank Eelens (UNFPA Sampling and Data Analysis Consultant), Guido Peraccini (UNFPA Database Consultant), Carol Boender (UN Women Gender Consultant), Nicholas McTurk (UNFPA), Sunita Caminha (UN Women), Scott Whoolery (UNICEF), Munkhtuya Altangerel (UNDP) and Ronny Lindstrom (UNFPA). Acknowledgements This Socio-Economic Impact Assessment of COVID-19 in Timor-Leste was led by UNDP and conducted in collaboration with UNFPA, UN Women and UNICEF. This study benefited from comments and feedback from all UN agencies in Timor-Leste including FAO (Solal Lehec, who provided valuable inputs to the sections related to food security in this report), ILO, IOM, WFP, WHO, the UN Human Rights Adviser Unit and UN Volunteers. SEIA team expresses its gratitude to the UN Resident Coordinator, Roy Trivedy, and the entire UN Country Team in Timor-Leste for providing overall guidance and support. We would like to sincerely thank all of the community members in Baucau, Bobonaro, Dili, Oecusse and Viqueque who participated in the SEIA questionnaires and interviews for being open and willing to share their stories and experiences for the development of this report. We would also like to thank the numerous individuals in government offices, institutions and organizations around the country who shared their time, expertise and insights to strengthen our understanding of the broader socio- economic context of Timor-Leste. -

Timor-Leste Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor

Timor-Leste Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor (BACET) Cooperative Agreement 486-A-00-06-00011-00 Quarterly Report July 01 - September 30, 2010 Submitted to: USAID/Timor-Leste Dili, Timor-Leste Angela Rodrigues Lopes da Cruz, Agreement Officer Technical Representative Submitted by: Land O’Lakes, Inc. International Development Division P. O. Box 64281 St. Paul, MN 55164-0281 U.S.A. October 2010 © Copyright 2010 by Land O'Lakes, Inc. All rights reserved. Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor CA # 486-A-00-06-00011-00 BUILDING AGRIBUSINESS CAPACITY IN EAST TIMOR USAID CA# 486-A-00-06-00011-00 Quarterly Report July - September 2010 Name of Project: Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor Locations: Fuiloro, Lautem District Maliana, Bobonaro District Natarbora, Manatutu District Dates of project: September 22, 2006 – September 30, 2011 Total estimated federal funding: $6,000,000 Total federal funding obligated: $6,000,000 Total project funds spent to September 30, 2010: $5,150,425 Contact in Timor-Leste: Michael J. Parr, Chief of Party Telephone: +670 331-2719 Mobile: +670 735-4382 E-mail: [email protected] Summary: BACET directly contributes to USAID/Timor- Leste’s agriculture and workforce development strategies for economic growth. though categorized as a capacity building and workforce development activity, many of the key activities of BACET have included infrastructure improvements, which are longer-term in nature. Similarly, teacher training and changed teaching methods have long-term impact. Quarterly Report July - September 2010 Land O'Lakes, Inc. Building Agribusiness Capacity in East Timor CA # 486-A-00-06-00011-00 Table of Contents 1. -

Dili to Baucau Highway Project Project Administration Manual

Project Administration Manual Project Number: 50211-001 Loan Number: LXXXX October 2016 Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste: Dili to Baucau Highway Project ABBREVIATIONS ADB = Asian Development Bank ADF = Asian Development Fund APFS = audited project financial statements CQS = consultant qualification selection DMF = design and monitoring framework EARF = environmental assessment and review framework EIA = environmental impact assessment EMP = environmental management plan ESMS = environmental and social management system GACAP = governance and anticorruption action plan GDP = gross domestic product ICB = international competitive bidding IEE = initial environmental examination IPP = indigenous people plan IPPF = indigenous people planning framework LAR = land acquisition and resettlement LIBOR = London interbank offered rate NCB = national competitive bidding NGOs = nongovernment organizations PAI = project administration instructions PAM = project administration manual PIU = project implementation unit QBS = quality based selection QCBS = quality- and cost based selection RRP = report and recommendation of the President to the Board SBD = standard bidding documents SGIA = second generation imprest accounts SOE = statement of expenditure SPS = Safeguard Policy Statement SPRSS = summary poverty reduction and social strategy TOR = terms of reference CONTENTS _Toc460943453 I. PROJECT DESCRIPTION 1 II. IMPLEMENTATION PLANS 2 A. Project Readiness Activities 2 B. Overall Project Implementation Plan 3 III. PROJECT MANAGEMENT ARRANGEMENTS 4 A. Project Implementation Organizations – Roles and Responsibilities 4 B. Key Persons Involved in Implementation 5 C. Project Organization Structure 6 IV. COSTS AND FINANCING 7 A. Detailed Cost Estimates by Expenditure Category 8 B. Allocation and Withdrawal of Loan Proceeds 9 C. Detailed Cost Estimates by Financier 10 D. Detailed Cost Estimates by Outputs/Components 11 E. Detailed Cost Estimates by Year 12 F. Contract and Disbursement S-curve 13 G. -

Dili to Baucau Highway Project

Updated Corrective Action Plan Project Number: 50211-001 May 2018 TIM: Dili to Baucau Highway Project Prepared by Ministry of Development and Institutional Reform for the Asian Development Bank. The Updated Corrective Action Plan is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s Board of Directors, Management or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. In preparing any country programme or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Ministry of Development and of Institutional Reform Dili to Baucau Highway Project CORRECTIVE ACTION PLAN (CAP) Completion Report Package A01-02 (Manatuto-Baucau) May 2018 Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste Corrective Action Plan (CAP) Ministry of Development and of Institutional Reform Completion Report Dili to Baucau Highway Project Table of Contents List of Tables ii List of Figures iii Acronyms iv List of Appendices v 1 INTRODUCTION 1 1.1 Objectives 1 1.2 Methodology 2 2 THE PROJECT 3 2.1 Overview of the Project 3 2.2 Project Location 3 3 LEGAL AND POLICY FRAMEWORK 5 3.1 Scope of Land Acquisition and Resettlement 5 3.2 Definition of Terms Use in this Report 5 4 RESETTLEMENT POLICY FRAMEWORK 0 5 THE RAP PROCESS 0 5.1 RAP Preparation 0 5.1.1 RAP of 2013 0 5.1.2 RAP Validation in 2015 0 5.1.3 Revalidation -

The General Prosecutor of the United Nations Transitiona& ) Administration

J~-- /', THE GENERAL PROSECUTOR OF THE UNITED NATIONS TRANSITIONA& ) ADMINISTRATION IN EAST TIMOR -' ~1 "-" AGAINST GASPAR LEITE I. INDICTMENT The General Prosecutor of the United Nations Transitional Administration in East Timor, pursuant to his authority under UNTAET Regulation 1999/1, 2000/11, 2000/15, 2000/16 and 2000/30 charges: GASPAR LEITE with MURDER As set forth in this indictment, the General Prosecutor requests the Special Panel for Serious Crimes of the District Court of Dili to take jurisdiction of this matter expeditiously. II. NAME AND PARTICULARS OF THE ACCUSED Name: Gaspar Leite Age: 43 Date of Birth: 6th March 1957 Place of Birth: Erolo, Aileu Nationality: East Timorese Location: Gleno Prison III. STATEMENT OF THE FACTS 1. On 30th August 1999 the people of East Timor voted in a referendLll11 for independence from the Republic of Indonesia. 2, Following the vote, there were attacks directed against the civilian population in, among other areas, the District of Aileu. 3. Within the District of Aileu is the village of HoHuLu. 4, By September 1999 Gaspar Leite had been a soldier with the TNI for about 9 years. During 1999 the TNI commander in the District of Aileu was Seargent Major Ali Cocoleo (Alikkokolok) of Kodim 1632. 5. On or about 8th September 1999 Ali Cocoleo (Alikkokolok) addressed a group of about twenty TNI personnel, including Gaspar Leite. Ali Cocoleo (Alikkokolok) gave instructions to the TNI personnel to attack the village of HoHuLu, to burn houses there and shoot people from the village. PURL: https://www.legal-tools.org/doc/51ab50/ ,r" i··-"')/ Io. -

53395-001: Water Supply and Sanitation Investment Project

Initial Environmental Examination March 2021 Timor-Leste: Water Supply and Sanitation Investment Project – Viqueque City Subproject (Part 1 of 5) Prepared by the Directorate General for Water and Sanitation, Ministry of Public Works for the Asian Development Bank. (page left Intentionally blank) i ABBREVIATIONS WSSIP - Water Supply and Sanitation Investment Project ACMs - Asbestos Containing Materials ADB - Asian Development Bank DED - Detailed Engineering Design DGAS - Directorate General for Water and Sanitation DNAP - National Directorate for Protected Areas DNCP - National Directorate for Pollution Control DNSA - National Directorate for Water Services EARF - Environmental Assessment and Review Framework EHS - Environment, Health and Safety EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EIS - Environmental Impact Statement EMP - Environmental Management Plan EMR - Environmental Monitoring Report ESS - Environmental Safeguard Specialist ESA - Environmental Safeguard Assistant FSTP - Faecal Sludge Treatment Plant GRM - Grievance Redress Mechanism IEE - Initial Environmental Examination IFC - International Finance Corporation MPW - Ministry of Public Works PA - Protected Area PD - Project Document PDC - Project Design Consultant PSC - Project Supervision Consultant PMU - Project Management Unit SEA - Superior Environmental Authority SEIS - Simplified Environmental Impact Statement CEMP - Site-specific Construction EMP SMASA - Municipal Water, Sanitation and Environment Services SPS - Safeguard Policy Statement TOR - Terms of Reference WDZ - Water -

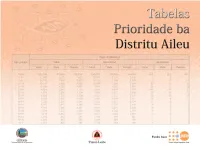

Aileu DPT Final.Indd

GLOSSÁRIU SENSUS TABELAS PRIORIDADE BA DISTRITU MANUFAHI NIAN 112 TTabelasa b e l a s PPrioridader i o r i d a d e bbaa DDistritui s t r i t u AileuA i l e u Testu © Kopiraite DNE ho UNFPA 2008 Direcção Nacional de Estatística (DNE) Fundu Populasaun Nasoens Unidas (UNFPA) i ii Y Y Y hsvs YY Y Y Y YY Y Y Y histriuisun2ptin2xe9eé2im2rel Y Y Y Y YYY YY YYYYYY gyEvs esYYY Y Y Y Y Y YY Y Y YYYYY YY YY Y Y Y YYYY Y YYY Y YYY YYY YY YYY YYY YY hss 2esvi Y YY YYY YYYY YYYY Y Y YY Y YY YY YYY YYY Y YY Y Y Y YY YY YYYY Y Y Y Y Y Y Y YYY Y Y Y YYY YYY Y YYYY Y Y Y Y YY Y Y YY Y Y Y Y Y YYYYYY YY Y Y Y YYY Y Y YYY evs Y YY YYYY YY YY YY Y Y Y YYYY YY Y Y Y Y Y YYY YY YY YY YYY YY YYYY YYYY Y YY Y Y YYYY YYYYYYYYY Y YY YYYY YYY Y Y Y Y Y YY Y YYY Y YY YY YY YYY Y YY Y Y Y Y Y Y Y ptinGum2xe9eé2em2hel YYY YY YYY Y Y Y YY YYYYYY YY Y YY Y Y Y Y YYYYYYYYYYYYYYY YY YY Y YYY Y Y Y Y YYYYYYYYYYYY Y Y YYY Y YYYYYY YYYYYYY Y YYYYYYYYYYYYYY Y YYYYY Y Y YYYYY YY YYYY Y YY YYYYYY vs sge Y Y Y YY Y Y YYY YYYYYY Y yspitál2no2ulínik Y YY Y YY YY ÑY Y Y vee iy Y Y Y Y YYYYY Y Y Y Y YYY Y YYYYYYYYYY YY YY YYY YY Y YY Y YYY Y Y Y Y eg we Y YYYY YY YYY Y YYY YYYY YYY Y YYY Y Y Y Y Y Y Y YY YY Y Y Y Y Y Y YY Y Y Y Y grg2@gommunity2relth2genterA Y Y YY Y Y Y gyyve Y Y YYYY Y YY Y entru2úde2uomunidde Y YY Y Y Y Y Y Y YY YYYY YY YY Y Y Y Y Y Y Y YY Y YYY Y YYY YY Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y YYY Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y Y YYY YY YY Y YYY Y YY YY Y YYYYY YYYYYYYYYYYY Y YYYYYY YY yr wieY Y YY Y YY YY YY Y Y fliz2uku YY YY Y YY Y iwisy Y Y Y YYYYY Y YY YYYYYYY YYY ve veeYY Y Y YY YY YY Y YY -

Fieldwork in Timor-Leste

Understanding Timor-Leste, on the ground and from afar (eds) and Bexley Nygaard-Christensen This ground-breaking exploration of research in Timor-Leste brings together veteran and early-career scholars who broadly Fieldwork in represent a range of fieldwork practices and challenges from colonial times to the present day. Here, they introduce readers to their experiences of conducting anthropological, historical and archival fieldwork in this new nation. The volume further Timor-Leste explores the contestations and deliberations that have been in Timor-Leste Fieldwork symptomatic of the country’s nation-building process, high- Understanding Social Change through Practice lighting how the preconceptions of development workers and researchers might be challenged on the ground. By making more explicable the processes of social and political change in Timor- Leste, the volume offers a critical contribution for those in the academic, policy and development communities working there. This is a must-have volume for scholars, other fieldworkers and policy-makers preparing to work in Timor-Leste, invaluable for those needing to understand the country from afar, and a fascinating read for anyone interested in the Timorese world. ‘Researchers and policymakers reading up on Timor Leste before heading to the field will find this handbook valuable. It is littered with captivating fieldwork stories. The heart-searching is at times searingly honest. Best of all, the book beautifully bridges the sometimes painful gap between Timorese researchers and foreign experts (who can be irritating know-alls). Academic anthropologists and historians will find much of value here, but the Timor policy community should appreciate it as well.’ – Gerry van Klinken, KITLV ‘This book is well worth reading by academics, activists and policy-makers in Timor-Leste and also those interested in the country’s development. -

Timor-Leste DHS 2009-10 Fact Sheet

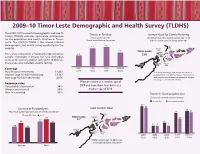

2009–10 Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Survey (TLDHS) The 2009–10 Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Trends in Fertility Unmet Need for Family Planning Survey (TLDHS) provides up-to-date information TFR for women for the Percent of currently married women age 15-49 on the population and health situation in Timor- 3-year period before the survey with an unmet need for family planning* Leste. The 2009–10 TLDHS is the second national demographic and health survey conducted in the 7.4 7.8 Dili 29% country. Liquiçá Lautem 5.7 Timor-Leste 29% Baucau 28% Aileu Manatuto 35% 27% The survey is based on a nationally representative 4.4 31% Ermera 30% Viqueque sample. It provides estimates for rural and urban 23% 31% Bobonaro Manufahi areas of the country and for each of the 13 districts. 42% 22% The survey also included anemia testing. Oecussi Covalima Ainaro 40% 17% 43% Coverage 1997 2002 2003 2009-10 IDHS MICS DHS TLDHS Households interviewed 11,463 *Currently married fecund women who want to Women (age 15–49) interviewed 13,137 postpone their next birth for two or more years or Men (age 15–54) interviewed 4,076 who want to stop childbearing altogether but are not using a contraceptive method Women marry at a median age of Response rates Households interviewed 98% 20.9 and have their first birth at a Women interviewed 95% median age of 22.4. Men interviewed 92% Trends in Contraceptive Use Percent of currently married women Any method Any modern method 27 25 Literacy of Respondents Total Fertility Rate 22 21 Percent of women and men age 15-49 -

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’S Office (RCO) Situation Report No

Timor-Leste: Floods UN Resident Coordinator’s Office (RCO) Situation Report No. 6 (As of 21 April 2021) This report is produced by RCO Timor-Leste in collaboration with humanitarian partners. It is issued by UN Timor-Leste. It covers the period from 16 to 21 April 2021. The next report will be issued on or around 28 April 2021. HIGHLIGHTS • Following the Government’s declaration of a state of calamity in Dili on 8 April, several humanitarian donors have provided additional humanitarian support the flood response, equivalent to nearly USD 10 million. • According to the latest official figures (21 April) from the Ministry of State Administration, which leads the Task Force for Civil Protection and Natural Disaster Management, a total of 28,734 households have reportedly been affected by the floods across all 13 municipalities. Of whom, 90% - or 25,881 households – are in Dili municipality. • The same report cites that currently there are 6,029 temporary displaced persons in 30 evacuation facilities across Dili, the worst-affected municipality. • 4,546 houses across all municipalities have reportedly been destroyed or damaged. • According to the preliminary assessment by the Ministry of Agriculture and Fisheries conducted in 9 municipalities to date, a total of 1,820 ha of rice crops and 190 ha of maize crops have been affected by the flooding. 13 28,734 4,546 30 41 Municipalities Total affected Houses Evacuation Fatalities affected (out households destroyed or facilities in of 13 across the damaged across Dili municipalities) country the country SITUATION OVERVIEW Heavy rains across the country from 29 March to 4 April have resulted in flash floods and landslides affecting all 13 municipalities in Timor-Leste to varying degrees, with the capital Dili and the surrounding low-lying areas the worst affected. -

The Study on Urgent Improvement Project for Water Supply System in East Timor

JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY EAST TIMOR TRANSITIONAL ADMINISTRATION THE STUDY ON URGENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM IN EAST TIMOR FINAL REPORT VolumeⅠ: SUMMARY REPORT FEBRUARY 2001 TOKYO ENGINEERING CONSULTANTS, CO., LTD. PACIFIC CONSULTANTS INTERNATIONAL SSS JR 01-040 THE STUDY ON URGENT IMPROVEMENT PROJECT FOR WATER SUPPLY SYSTEM IN EAST TIMOR FINAL REPORT CONSTITUENT VOLUMES VOLUME Ⅰ SUMMARY REPORT VOLUME Ⅱ MAIN REPORT VOLUME Ⅲ APPENDIX VOLUME Ⅳ QUICK PROJECT IMPLEMENTATION MANUAL Foreign Exchange Rate: USD 1.00 = INDONESIA RUPIAH 9,500 AUD 1.00 = JPY 58.50 USD 1.00 = JPY 111.07 (Status as of the 30 November 2000) PREFACE In response to a request from the United Nations Transitional Administration of East Timor, the Government of Japan decided to conduct The Study on Urgent Improvement Project for Water Supply System in East Timor and entrusted the study to the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA). JICA selected and dispatched a study team headed by Mr. Kazufumi Momose of Tokyo Engineering Consultants Co., Ltd. in association with Pacific Consultants International to East Timor, twice between February 2000 and February 2001. The team held discussions with the officials concerned of the East Timor Transitional Administration and Asian Development Bank which is a trustee of East Timor Trust Fund and conducted field surveys in the study area. Based on the field surveys, the Study Team conducted further studies and prepared this final report. I hope that this report will contribute to the promotion of this project and to the enhancement of friendly relationship between Japan and East Timor Finally, I wish to express my sincere appreciation to the officials concerned of the East Timor Transitional Administration for their close cooperation extended to the Study.