Ian Thomson Phd Thesis Vol 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ROAD BOOK from Venice to Ferrara

FROM VENICE TO FERRARA 216.550 km (196.780 from Chioggia) Distance Plan Description 3 2 Distance Plan Description 3 3 3 Depart: Chioggia, terminus of vaporetto no. 11 4.870 Go back onto the road and carry on along 40.690 Continue straight on along Via Moceniga. Arrive: Ferrara, Piazza Savonarola Via Padre Emilio Venturini. Leave Chioggia (5.06 km). Cycle path or dual use Pedestrianised Road with Road open cycle/pedestrian path zone limited traffic to all traffic 5.120 TAKE CARE! Turn left onto the main road, 41.970 Turn left onto the overpass until it joins Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track Gravel or dirt-track the SS 309 Romea. the SS 309 Romea highway in the direction of Ravenna. Information Ferry Stop Sign 5.430 Cross the bridge over the river Brenta 44.150 Take the right turn onto the SP 64 major Gate or other barrier Moorings Give way and turn left onto Via Lungo Brenta, road towards Porto Levante, over the following the signs for Ca' Lino. overpass across the 'Romea', the SS 309. Rest area, food Diversion Hazard Drinking fountain Railway Station Traffic lights 6.250 Carry on, keeping to the right, along 44.870 Continue right on Via G. Galilei (SP 64) Via San Giuseppe, following the signs for towards Porto Levante. Ca' Lino (begins at 8.130 km mark). Distance Plan Description 1 0.000 Depart: Chioggia, terminus 8.750 Turn right onto Strada Margherita. 46.270 Go straight on along Via G. Galilei (SP 64) of vaporetto no. -

Andrea Corsali and the Southern Cross

Andrea Corsali and the Southern Cross Anne McCormick Hordern House 2019 1 In 1515 Andrea Corsali, an Italian under the patronage of the Medici family, accompanied a Portuguese voyage down the African coast and around the Cape of Good Hope, en route to Cochin, India. On his return Corsali’s letter to his patron describing the voyage was published as a book which survives in only a handful of copies: CORSALI, Andrea. Lettera di Andrea Corsali allo Illustrissimo Signore Duca Iuliano de Medici, Venuta Dellindia del Mese di Octobre Nel M.D.XVI. [Colophon:] Stampato in Firenze per Io. Stephano di Carlo da Pavia. Adi. xi.di Dicembre Nel. M.D.XV1. This book included the earliest illustration of the stars of the Crux, the group of stars today known as the Southern Cross. This paper will explore the cultural context of that publication, along with the significance of this expedition, paying attention to the identification and illustration of the stars of the Southern Cross; in particular, I shall investigate why the book was important to the Medici family; the secrecy often attaching to geographical information acquired during the Age of Discovery; Andrea Corsali’s biography; and printing in Florence at this period; and other works issued by the printer Giovanni Stefano from Pavia. Corsali’s discoveries, particularly the ground-breaking astronomical report and illustration of the Southern Cross off the Cape of Good Hope, remained a navigational aid to voyages into the Southern Ocean and on to The East and the New World for centuries to follow, and ultimately even played a part in the European discovery of Australia. -

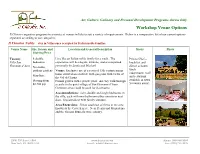

Comparative Venue Sheet

Art, Culture, Culinary and Personal Development Programs Across Italy Workshop Venue Options Il Chiostro organizes programs in a variety of venues in Italy to suit a variety of requirements. Below is a comparative list of our current options separated according to our categories: Il Chiostro Nobile – stay in Villas once occupied by Italian noble families Venue Name Size, Season and Location and General Description Meals Photo Starting Price Tuscany 8 double Live like an Italian noble family for a week. The Private Chef – Villa San bedrooms experience will be elegant, intimate, and accompanied breakfast and Giovanni d’Asso No studio, personally by Linda and Michael. dinner at home; outdoor gardens Venue: Exclusive use of a restored 13th century manor lunch house situated on a hillside with gorgeous with views of independent (café May/June and restaurant the Val di Chiana. Starting from Formal garden with a private pool. An easy walk through available in town $2,700 p/p a castle to the quiet village of San Giovanni d’Asso. 5 minutes away) Common areas could be used for classrooms. Accommodations: twin, double and single bedrooms in the villa, each with own bathroom either ensuite or next door. Elegant décor with family antiques. Area/Excursions: 30 km southeast of Siena in the area known as the Crete Senese. Near Pienza and Montalcino and the famous Brunello wine country. 23 W. 73rd Street, #306 www.ilchiostro.com Phone: 800-990-3506 New York, NY 10023 USA E-mail: [email protected] Fax: (858) 712-3329 Tuscany - 13 double Il Chiostro’s Autumn Arts Festival is a 10-day celebration Abundant Autumn Arts rooms, 3 suites of the arts and the Tuscan harvest. -

Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171

EuFERRARcharistic MiraAcle of ITALY, 1171 This Eucharistic miracle took place in Ferrara, in the Basilica of Saint Mary in Vado, Bull of Eugene IV (1442) on Easter Sunday, March 28, 1171. While celebrating Easter Mass, Father Pietro John Paul II pauses before the ceiling vault in Ferrara da Verona, the prior of the basilica, reached the moment of breaking the consecrated Church of Saint Mary in Vado, Ferrara Host when he saw blood gush from it and stain the ceiling Interior of the basilica vault above the altar with droplets. In 1595 the vault was enclosed within a small Bodini, The Miracle of the Blood. Painting on the ceiling shrine and is still visible today near the shrine in the monumental Basilica of Santa Maria in Vado. Detail of the ceiling vault stained with Blood Shrine that encloses the Holy Ceiling Vault (1594). The ceiling vault stained with Blood Right side of the cross n March 28, 1171, the prior of the Canons was rebuilt and expanded on the orders of Duke Miraculous Blood.” Even today, on the 28th day Regular Portuensi, Father Pietro da Verona, Ercole d’Este beginning in 1495. of every month in the basilica, which is currently was celebrating Easter Mass with three under the care of Saint Gaspare del Bufalo’s confreres (Bono, Leonardo and Aimone). At the regarding Missionaries of the Most Precious Blood, moment of the breaking of the consecrated Host, thisThere miracle. are Among many the mostsources important is the Eucharistic Adoration is celebrated in memory of It sprung forth a gush of Blood that threw large Bull of Pope Eugene IV (March 30, 1442), the miracle. -

L-G-0010822438-0026417920.Pdf

Super alta perennis Studien zur Wirkung der Klassischen Antike Band 17 Herausgegeben von Uwe Baumann, MarcLaureys und Winfried Schmitz DavidA.Lines /MarcLaureys /Jill Kraye (eds.) FormsofConflictand Rivalries in Renaissance Europe V&Runipress Bonn UniversityPress ® MIX Papier aus verantwor- tungsvollen Quellen ® www.fsc.org FSC C083411 Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie;detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-8471-0409-4 ISBN 978-3-8470-0409-7 (E-Book) Veröffentlichungen der Bonn University Press erscheinen im Verlag V&Runipress GmbH. Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung des „Leverhulme Trust International Network“ (Großbritannien) zum Thema „RenaissanceConflictand Rivalries:Cultural Polemics in Europe, c. 1300–c.1650“ und der Philosophischen Fakultätder UniversitätBonn. 2015, V&Runipress in Göttingen /www.v-r.de Alle Rechte vorbehalten. Das Werk und seine Teile sind urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung in anderen als den gesetzlich zugelassenen Fällen bedarf der vorherigen schriftlichen Einwilligung des Verlages. Printed in Germany. Titelbild:Luca della Robbia, relieffor the Florentine campanile, c. 1437 (Foto:Warburg Institute, Photographic Collection, out of copyright) Druck und Bindung:CPI buchbuecher.de GmbH, Birkach Gedruckt aufalterungsbeständigem Papier. Contents DavidA.Lines /MarcLaureys /JillKraye Foreword .................................. -

La Lingua Litteraria Di Guarino Veronese E La Cultura Teatrale a Ferrara Nella Prima Metà Del XV Secolo

Annali Online di Ferrara - Lettere Vol. 2 (2009) 225/256 DOMENICO GIUSEPPE LIPANI La lingua litteraria di Guarino Veronese e la cultura teatrale a Ferrara nella prima metà del XV secolo 1. Etichette e identità L’etichetta è una comoda scorciatoia per riconoscere in un bailamme di oggetti simili lo scarto che irriducibilmente li diversifica, per dare conto di identità plurime ad un primo sguardo, per trovare con rapidità ciò che già si sta cercando. Per questo le etichette riportano l’estremamente peculiare, lo specifico, il distintivo. Ma le etichette, non a caso, si appiccicano, perché sono estranee e superficiali. Quando si voglia non trovare ma veramente cercare, le etichette sono inservibili. La storia del teatro ne è piena. Giusto per fare degli esempi, alle origini della ricomparsa del teatro in Occidente c’è l’etichetta dramma liturgico e all’opposto cronologico, prima dell’esplosione novecentesca, la nascita della regia. Etichette, per l’appunto, che, attaccate per indicare, hanno finito per ridurre al silenzio ogni complessità culturale sottostante. Della sperimentazione teatrale a Ferrara nel Quattrocento, di quella stagione di grande fermento culturale e di radicato progetto politico si è spesso riferito usando l’etichetta di festival plautini, creando così il vuoto prima, dopo e in mezzo alle messe in scena di Plauto e Terenzio. Come se i tempi brevi di quegli eventi spettacolari non fossero intrecciati ai tempi lunghi della vita culturale cittadina. Come ricordava Braudel, però, «tempi brevi e tempi lunghi coesistono e sono inseparabili»1 e voler vedere gli uni prescindendo dagli altri significa fermarsi alla superficie dell’etichetta. -

Flavio Biondo's Italia Illustrata

Week V: Set Reading – Primary Source Flavio Biondo, on the revival of letters, from his Italia illustrata Editor’s Note: Flavio Biondo (1392-1463), also (confusingly) known as Biondo Flavio, was born in Forlì, near Bologna, but much of his career was spent at the papal curia, where he worked as secretary to successive Popes. At the same time, he wrote works of history and of topography. The Italia illustrata, which he worked on in the late 1440s and early 1450s, was intended to describe the geography of the regions of Italy but, in doing so, Biondo discoursed on the famous men of each region and, in the context in the section of his home region of the Romagna, provided a brief history of the revival of letters in his own lifetime. Those who truly savour Latin literature for its own taste, see and understand that there were few and hardly any who wrote with any eloquence after the time of the Doctors of the Church, Ambrose, Jerome and Augustine, which was the moment when the Roman Empire was declining – unless among their number should be put St Gregory and the Venerable Bede, who were close to them in time, and St Bernard, who was much later.1 Truly, Francesco Petrarca [Petrarch], a man of great intelligence and greater application, was the first of all to begin to revive poetry and eloquence.2 Not, however, that he achieve the flower of Ciceronian eloquence with which we see many in our own time are decorated, but for that we are inclined to blame the lack and want of books rather than of intelligence. -

PHILOPOEMEN IMMODICUS and SUPERBUS and SPARTA the Decision Taken by the Achaean League in the Autumn of 192 B.G at Aegium To

PHILOPOEMEN IMMODICUS AND SUPERBUS AND SPARTA The decision taken by the Achaean League in the autumn of 192 B.G at Aegium to wage war against the Aetolians and their allies was crucial to the Greeks and their future. Greece proper had been divided for generations among several political bodies — and, in fact, had never been united into one state. Yet all those known as Έλληνες felt the natural human desire to avoid the unnecessary violence, bloodshed, and self-destruction engendered by ceaseless competition for preeminence and hegemomy in the domestic arena. The so-called “Tragic Historians” adopted these emotions as the leitmotif of their principal efforts to delineate the deeds and omissions of the Greek leadership and populace.1 Rome’s powerful political-strategical penetration east of the Adriatic sea, into Mainland Greece, particularly during the later decades of the third century B.C, undermined the precarious balance of internal Greek politics. The embarrassment which had seized most of Greece is easily understandable. Yet the Achaeans at Aegium do not appear to have been inspired by the memory of their ancestors’ resistance to the Persians. The Achaean leaders, Philopoemen not excluded, rejected Aetolian pleas for help or, at least, non-intervention in the struggle that they had started in the name of Έλληνες for the whole of Greece. Somewhat surprisingly, the Achaean leaders hastened to declare war on the Aetolians, anticipating even the Roman crossing to Greece2. These are the bare facts available to us (Livy 35.50.2-6). However, the conventional interpretation of these occurrences derived from Polybius 3 tends to be pathetic more than historical, and consti tute an embellished portrait of Achaean policy and politicians of those days rather than an honest guide to the political realities of the Έλληνες and Greece proper. -

University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan LINDA JANE PIPER 1967

This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 66-15,122 PIPER, Linda Jane, 1935- A HISTORY OF SPARTA: 323-146 B.C. The Ohio State University, Ph.D., 1966 History, ancient University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan LINDA JANE PIPER 1967 All Rights Reserved A HISTORY OF SPARTA: 323-1^6 B.C. DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Linda Jane Piper, A.B., M.A. The Ohio State University 1966 Approved by Adviser Department of History PREFACE The history of Sparta from the death of Alexander in 323 B.C; to the destruction of Corinth in 1^6 B.C. is the history of social revolution and Sparta's second rise to military promi nence in the Peloponnesus; the history of kings and tyrants; the history of Sparta's struggle to remain autonomous in a period of amalgamation. It is also a period in Sparta's history too often neglected by historians both past and present. There is no monograph directly concerned with Hellenistic Sparta. For the most part, this period is briefly and only inci dentally covered in works dealing either with the whole history of ancient Sparta, or simply as a part of Hellenic or Hellenistic 1 2 history in toto. Both Pierre Roussel and Eug&ne Cavaignac, in their respective surveys of Spartan history, have written clear and concise chapters on the Hellenistic period. Because of the scope of their subject, however, they were forced to limit them selves to only the most important events and people of this time, and great gaps are left in between. -

An Introduction to Latin Literature and Style Pursue in Greater Depth; (C) It Increases an Awareness of Style and Linguistic Structure

An Introduction to Latin Literature and Style by Floyd L. Moreland Rita M. Fleischer revised by Andrew Keller Stephanie Russell Clement Dunbar The Latin/Greek Institute The City University ojNew York Introduction These materials have been prepared to fit the needs of the Summer Latin Institute of Brooklyn College and The City University of New York. and they are structured as an appropriate sequel to Moreland and Fleischer. Latin: An Intensive Course (University of California Press. 1974). However, students can use these materials with equal effectiveness after the completion of any basic grammar text and in any intermediate Latin course whose aim is to introduce students to a variety of authors of both prose and poetry. The materials are especially suited to an intensive or accelerated intermediate course. The authors firmly believe that, upon completion of a basic introduction to grammar. the only way to learn Latin well is to read as much as possible. A prime obstacle to reading is vocabulary: students spend much energy and time looking up the enormous number of words they do not know. Following the system used by Clyde Pharr in Vergil's Aeneid. Books I-VI (Heath. 1930), this problem is minimized by glossing unfamiliar words on each page oftext. Whether a word is familiar or not has been determined by its occurrence or omission in the formal unit vocabularies of Moreland and Fleischer, Latin: An Intensive Course. Students will need to know the words included in the vocabularies of that text and be acquainted with some of the basic principles of word formation. -

Greek Studies in Italy: from Petrarch to Bruni

Greek Studies in Italy: From Petrarch to Bruni The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Hankins, James. 2007. Greek studies in Italy: From Petrarch to Bruni. In Petrarca e il Mondo Greco Atti del Convegno Internazionale di Studi, Reggio Calabria, 26-30 Novembre 2001, ed. Michele Feo, Vincenzo Fera, Paola Megna, and Antonio Rollo, 2 vols., Quaderni Petrarcheschi, vols. XII-XIII, 329-339. Firenze: Le Lettere. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:8301600 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA GREEK STUDIES IN ITALY: FROM PETRARCH TO BRUNI Comparing with the mind's eye the revival of Greek studies that took place in Avignon and Florence in the middle decades of the fourteenth century with the second revival that began in Florence three decades later, two large problems of historical interpretation stand out, which have not yet, I hope, entirely exhausted their interest—even after the valuable studies of Giuseppe Cammelli, R. J. Leonertz, Roberto Weiss, Agostino Pertusi, N. G. Wilson, Ernesto Berti, and many others. The first problem concerns the reason why (to use Pertusi's formulation) Salutati succeeded where Boccaccio failed: why no Latin scholar of the mid-fourteenth century succeeded in learning classical Greek, whereas the students of Manuel Chrysoloras were able not only to learn Greek themselves, but to pass down their knowledge to later generations. -

9789004272989.Pdf

Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768) Brill’s Studies in Intellectual History General Editor Han van Ruler (Erasmus University Rotterdam) Founded by Arjo Vanderjagt Editorial Board C.S. Celenza ( Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore) M. Colish (Yale University) J.I. Israel (Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton) A. Koba (University of Tokyo) M. Mugnai (Scuola Normale Superiore, Pisa) W. Otten (University of Chicago) VOLUME 237 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/bsih Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768) Classicist, Hebraist, Enlightenment Radical in Disguise By Ulrich Groetsch LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration and frontispiece: Portrait of Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768) by Gerloff Hiddinga, 1749. Private collection. Photo by Sascha Fuis, Cologne 2004. Courtesy of Hinrich Sieveking, Munich. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Groetsch, Ulrich. Hermann Samuel Reimarus (1694–1768) : classicist, hebraist, enlightenment radical in disguise / by Ulrich Groetsch. pages cm. — (Brill’s studies in intellectual history, ISSN 0920-8607 ; VOLUME 237) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-27299-6 (hardback : alk. paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-27298-9 (e-book) 1. Reimarus, Hermann Samuel, 1694–1768. I. Title. B2699.R44G76 2015 193—dc23 2014048585 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, ipa, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. issn 0920-8607 isbn 978-90-04-27299-6 (hardback) isbn 978-90-04-27298-9 (e-book) Copyright 2015 by Koninklijke Brill nv, Leiden, The Netherlands. Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill, Brill Hes & De Graaf, Brill Nijhoff, Brill Rodopi and Hotei Publishing.