Fighting from Home Studies in Canadian Military History

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

C/Clyf D/L~ Calgary, Alta

, ," T_.... h.:..u_rs_da..:y:.:,_JII_I..:ay~1l.:.._1_96 __ 7 _________ ~.,;... _______..:..T H E JEW ISH PO S T Page Forty-seven Thursday, May 11, 1967 THE JEWISH POST '"!!!!!==="'j=""':============="--""--"",-,,,,.",;...-""". - I~=====::::;"================="'i III with 31 kills, died on a grass air- Page Forty-SlX Sincere Greetings on 15rael's Independence Day· strip leased by the Jews outside 'suit. Soon he was showing his log :=~~~~~=~=~==~~=======;"".",=~ Sincere Greetings on Israel's Independence Day Rome. He was being checked out in a Canadian Noresman, considered : book to a firm of prominent Jewish Sincere Greetings on Israel's Independence Day Sincere Greetings on Israel's Independence Day lawyers in the city. They started one of the safest aircraft in the him on his way to Israel. The N'OW IN CALGA1RY! world. With Beaurling was Lennie sequel came at a seaside cafe in Cohen, a Jewish RAF flyer who had Modern Lathing Ltd. Tel Aviv one Saturday night in the M. Brener &. Co. JEWISH·TYPE BREAD became famous as the Lion of Malta fall when Wilson waited in vain for THE H.R. LABEL IS YOUR GUARANTEE during World War II. (An air-sea "BE MODERN - CALL MODERN" his old buddy. Canter had been CHARTERED ACCOUNTANTS rescue pilot, Cohen had crash I&y a Skilled Ifalian Baker landed on the beach of Lampedw;a. SUPPI.JERS AND ERECTORS OF killed that afternoon when a wing was blown off his DC-3, Office Phones: 269-7229 - 269·5432 ALWAYS IN THE LEAD IN THE I a small island of, North Mrica, Dry Wall - Lath and Piaster - Steel Stud Partitions Beurling Killed CHALA (Egg Twist) where 127 Italian soldiers surren Wilson's story is typical of the "A Maichel" NEWEST PRESENTATION dered to him.) 2402 - 10 Ave. -

Proquest Dissertations

"The House of the Irish": Irishness, History, and Memory in Griffintown, Montreal, 1868-2009 John Matthew Barlow A Thesis In the Department of History Present in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Concordia University, Montreal, Quebec, Canada March 2009 © John Matthew Barlow, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63386-1 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63386-1 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre im primes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Air and Space Power Journal, Published Quarterly, Is the Professional Flagship Publication of the United States Air Force

Air Force Chief of Staff Gen John P. Jumper Commander, Air Education and Training Command Gen Donald G. Cook http://www.af.mil Commander, Air University Lt Gen Donald A. Lamontagne Commander, College of Aerospace Doctrine, Research and Education Col Bobby J. Wilkes Editor Col Anthony C. Cain http://www.aetc.randolph.af.mil Senior Editor Lt Col Malcolm D. Grimes Associate Editors Lt Col Michael J. Masterson Maj Donald R. Ferguson Professional Staff Marvin W. Bassett, Contributing Editor Larry Carter, Contributing Editor Mary J. Moore, Editorial Assistant http://www.au.af.mil Steven C. Garst, Director of Art and Production Daniel M. Armstrong, Illustrator L. Susan Fair, Illustrator Ann Bailey, Prepress Production Manager Air and Space Power Chronicles Luetwinder T. Eaves, Managing Editor The Air and Space Power Journal, published quarterly, is the professional flagship publication of the United States Air Force. It is designed to serve as an open forum for the pres entation and stimulation of innovative thinking on military http://www.cadre.maxwell.af.mil doctrine, strategy, tactics, force structure, readiness, and other matters of national defense. The views and opinions expressed or implied in the Journal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or de partments of the US government. In this edition, articles not bearing a copyright notice may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. Articles bearing a copyright notice may be reproduced for any US government purpose without permission. -

Montreal Intercultural Profile June 2019

Montreal Intercultural Profile June 2019 Index 1. Introduction 2 2. Federal and provincial policy context 3 3. Local Diversity and Policy Context 8 4. Governance and democratic participation 13 5. Welcome policies 14 6. Education, training and language 15 7. Employment and business 17 8. Public spaces, neighbourhoods and social mixing 19 9. Mediation 21 10. Civil Society 22 11. Culture 23 12. Conclusions and recommendations 26 ANNEX 1. VISIT PROGRAMME 28 Montreal Intercultural Profile This report is based upon the visit of the Council of Europe’s expert team on 13 and 14 May 2019 comprising Ivana d’Alessandro and Daniel de Torres. It should be read in parallel with the Council of Europe’s response to Montreal ICC Index questionnaire1, which contains many recommendations and pointers to examples of good practice. 1. Introduction Montréal is located in Québec province, south-eastern Canada. With 1,704,694 inhabitants (2016) it is the second most-populous city in the country. At 365 km2, the city of Montreal occupies about three-fourths of Montréal Island (Île de Montréal), the largest of the 234 islands of the Hochelaga Archipelago, one of three archipelagos near the confluence of the Ottawa and St. Lawrence rivers. The city was founded in 1642 by European settlers in view to establish a Catholic missionary community on Île de Montréal. It was to be called Ville-Marie, after the Virgin Mary. Its current name comes from Mount Royal, the triple-peaked hill in the heart of the city. From the time of the confederation of Canada (1867), Montréal was the largest metropolitan centre in the country until it was overtaken by Toronto in the ‘70s. -

Montreal Essentials

ESSENTIALS Montreal Essentials Origin of the Name: It’s generally accepted that Montreal got its name from the mountain at its centre. The theory is that French explorer Jacques Cartier applied the name “Mont Royal” to the modest peak he ascended when he visited the area in 1535. While the French settle - ment that was established a century later was initially called Ville Marie (in honour of the Virgin Mary), by the 1700s the name “Montreal” (a contraction of Mont Royal) was commonly used. Coat of Arms: Adopted in 1833 and modified in 1938. Emblazoned on a silver field is a heraldic cross meant to reflect Christian motives and principles. On the coat of arms are also four emblems: The fleur-de-lis of the Royal House of Bourbon representing the French settlers, the Lancastrian rose for the English component of the city’s population, the thistle represents those of Scottish descent; and the Irish shamrock rep - resents early Irish settlers. Montreal’s Motto: Concordia Salus (Salvation through harmony). 17 ESSENTIALS Official Flag: First displayed in May 1939. The flag is emblazoned with holiday known as St. Jean-Baptiste Day (feast day of St. John the the same heraldic symbols as those of the coat of arms. Baptist). Other holidays are New Years Day (January 1), Good Friday (the Friday before Easter), Canada Day (July 1), Labour Day (the first Logo: Created in 1981, the logo is shaped like a flower, in which each petal Monday in September), Thanksgiving (second Monday in October), forms the letters V and M, the initials of the name “Ville de Montréal.” Remembrance Day (November 11), Christmas Day (December 25) and Boxing Day (December 26). -

Malta Spitfire: the Diary of an Ace Fighter Pilot Free

FREE MALTA SPITFIRE: THE DIARY OF AN ACE FIGHTER PILOT PDF George F. Beurling | 256 pages | 19 Aug 2011 | GRUB STREET | 9781906502980 | English | London, United Kingdom Malta Spitfire: The Diary of an Ace Fighter Pilot by George Beurling, Paperback | Barnes & Noble® Goodreads helps you keep track of books you want to read. Want to Read saving…. Want to Read Currently Reading Read. Other editions. Enlarge cover. Error rating book. Refresh and try again. Open Preview See a Problem? Details if other :. Thanks for telling us about the problem. Return to Book Page. Preview — Malta Spitfire by George Beurling. An aviator's true story of WWII air combat, including two dramatic weeks in the skies above the besieged island of Malta. Twenty-five thousand feet above Malta--that is where the Spitfires intercepted the Messerschmitts, Macchis, and Reggianes as they swept eastward in their droves, screening the big Junkers with their bomb loads as they pummeled the island beneath: the mo An aviator's true story of WWII air combat, including two dramatic weeks in the skies above the besieged island of Malta. Twenty-five thousand feet above Malta--that is where the Spitfires intercepted the Messerschmitts, Macchis, and Reggianes as they swept eastward in their droves, screening the big Junkers with their bomb loads as they pummeled the island beneath: the most bombed patch of ground in the world. One of those Spitfire pilots was George Beurling, nicknamed "Screwball," who in fourteen flying days destroyed twenty-seven German and Italian aircraft and damaged many more. Hailing from Canada, Beurling finally made it to Malta in the summer of after hard training and combat across the Channel. -

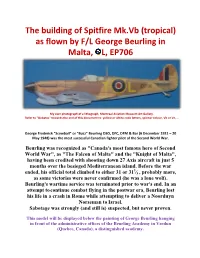

The Building of Spitfire Mk.Vb (Tropical) As Flown by F/L George Beurling in Malta, L, EP706

The building of Spitfire Mk.Vb (tropical) as flown by F/L George Beurling in Malta, L, EP706 My own photograph of a lithograph, Montreal Aviation Museum Art Gallery. Refer to "Debates" towards the end of this document re: yellow or white code letters, spinner colour, Vb or Vc, … George Frederick "Scewball" or "Buzz" Beurling DSO, DFC, DFM & Bar (6 December 1921 – 20 May 1948) was the most successful Canadian fighter pilot of the Second World War. Beurling was recognized as "Canada's most famous hero of Second World War", as "The Falcon of Malta" and the "Knight of Malta", having been credited with shooting down 27 Axis aircraft in just 5 months over the besieged Mediterranean island. Before the war 1 ended, his official total climbed to either 31 or 31 ⁄3 , probably more, as some victories were never confirmed (he was a lone wolf). Beurling's wartime service was terminated prior to war's end. In an attempt to continue combat flying in the postwar era, Beurling lost his life in a crash in Rome while attempting to deliver a Noorduyn Norseman to Israel. Sabotage was strongly (and still is) suspected, but never proven. This model will be displayed below the painting of George Beurling hanging in front of the administrative offices of the Beurling Academy in Verdun (Quebec, Canada), a distinguished academy. The kit: Airfix A12005A, 1:24 scale The original molds date back to 1970. It has had many iterations as a Mk.Ia; in 2005, Airfix re-issued it as a Vb; it seems the tropical version dates back to 2013, complete with new decals. -

Our Future Policy Aim Unfaltering

PAGE 14 EIHTOKIAI. PAGE of THE IIKTHOIT TIMES * January Report on Liquor Flynn Case One Side, Big Boy! Beurling Death up. the report of the liquor study'commission GOP SUMMEDmade one fundamental recommendation which strikes Upsets bluntly at the source of most liquor control troubles. To Axis Fliers; That valuable advice to the state government, is: j Cloakrooms Enforce the law strictly; make penalties severe, and Aim Unfaltering eliminate more than a thin! of Detroit saloons by running : Wallace Talks Finding violators out of * Beurling business. Fewer, Buzz” Beurling—Sergeant Pilot George If the state liquor control commission will invoke this Fewer Listeners of Verdun, Que. —has made the RAF. He asks and t» Malta, policy, it will win public acclaim at last and definitely transferred to the hell-hole of war, "most By l»\l M \I.LON s-pot on Now, the block the dangerous movement back to the lawlessness L bombed earth.'* action! Continue thrilling exploits this ace aces, who shot of prohibition. II’ASHINGTON. Jan. 27. Sen of fabulous of • • • ate Republicans are fuming down 29 Axis planes, in Chapter IV below. was a very thorough report by Federal Judge at the imp uls i v e leadership By G£ROLD FRANK thrust upon ihem in Iho Frank A. Picard, Harry Rickel and Myron A. Keys, Flynn ia June, 1942, in THIS rase by their New Hampshire It Malta. who the as a is the harbor of Valetta, started their study of liquor system nearly a senator, Stv les Bridges. Silent graveyard grand studded with the hulls wrecked ships. -

Write Me a Film?

WRITE ME A FILM? A Symposium by Canadian Filmmakers INTRODUCTION Hugo McPherson WHAT ARE THE CONNECTIONS vision. So we will regard this as a quartet, between writing and cinema in Canada? not in musical terms, where four voices There is no authoritative answer to this play together, but in film terms, where question. Instead, there are almost as discordant voices achieve a special har- many answers as there are film makers mony or dissonance in a completed work. and writers. Hence a symposium, the In this script, Ian MacNeill, film form most closely related to the group maker, and former Director of English effort of making a film. I have not, how- Programme, relates the costs of film- ever, taken a further step towards film: making to the individual effort of the I have not asked each contributor to sub- writer. William Weintraub, novelist, mit his article to a score of colleagues script-writer and film-maker, dramatizes to have it revised, praised, condemned, the four-way problem of scripted and cut, expanded, re-titled, or changed to unscripted films. Guy Glover, producer, another subject before it reached the page-proof (or test print) stage. That and Director of English Programme, em- would have been too close to the real phasizes the inter-disciplinary, non-liter- process; and of course the budget for a ary nature of the film art. And Jacques symposium is not a film budget. Godbout, film maker, novelist, poet, and What follows reveals the attitudes of Directeur de la production française, four working film makers and writers looks philosophically at fiction and film, who occupy important places at the Na- and finds that words and visual images— tional Film Board. -

Renvois, Pp 741-749 95 Extraits D'une

Renvois, pp 741-749 rn73 95 Extraits d' une conference presidee par le Generalfeldmarschall Milch, 6 juillet l 943, archives de Milch, traduit vers I' Anglais dans SHist SG R II 217, bobine 21 96 Ibid. ; Price, Instruments of Darkness, r 46; Herrmann, Eagle's Wings, r68ff 97 Aders, German Night Fighter Force, 85, 126; David Pritchard, The Radar War, (Wellingborough 1989), r 55 98 Oberst A.D. Mirr, « Development of German aircraft armament to war's end », etude historique de [' USA F n° 193, SHist 81/960, 9off ; « Schrage Musik », Jiigerblatt, xvi, juillet-aofit 1967, r6-18 ; Aders, German Night Fighter Force, 66-7; compte rendu d'interrogatoire d'Heron, « Questionnaire for returned aircrew - loss of bomber aircraft », dans SHist 18 r.oor (024) 99 Grabmann, « German air defense, 1933-1945 », juin 1957, etude historique de l'usAF n° 164, SHist 86/451 , images 9roff et I071ff ; commentaires de Galland lors de la conference presidee par Milch, 5 janv. 1943, dans Jes archives de Milch, SHist SGR n 217, bobine r8, images 3990--3999 ; proces-verbal de la conference copresidee par Gering et Milch, r8 mars 1943, archives de Milch, copie dans SHist SGR 11 217, bobine 62, images 5462-5500, 5546-5549 CHAPITRE T9 : A L'ERE DE L' ELECTRONIQ UE : HAMBOU RG ET LA SU ITE r Ordre d 'operation n° l 73 du Bomber Command, 27 mai 1943, SHist r 8 l .009 (06792); Martin Middlebrook, The Battle of Hamburg, (Londres 1980), 93-117 ; Martin Middlebrook, The Berlin Raids (Londres 1988), 8ff ; Gordon Musgrove, Operation Gomorrah (Londres 1981), 1-13 2 Webster et Frankland, -

Alvin York the Most Decorated Pacifist of World War I

Military Despatches Vol 11 May 2018 Ten military blunders of WWII Ten military mistakes that proved costly Under three flags The man who fought for three different nations Head-to-Head World War II fighter aces Battlefield The Battle of Spion Kop The Boer Commandos A citizen army that was forged in battle For the military enthusiast Military Despatches May 2018 What’s in this month’s edition Feature Articles 6 Top Ten military blunders of World War II Click on any video below to view Ten military operations of World War II that had a major impact on the final outcome of the war. How much do you know about movie theme 16 Under three flags songs? Take our quiz Some men have fought in three different wars, but rarely have they fought for three different countries. and find out. This was one such man. Page 6 20 Rank Structure - WWII German Military Hipe’s Wouter de The old South African Over the next few months we will be running a se- Goede interviews former Defence Force used ries of articles looking at the rank structure of vari- 28’s gang boss David a mixture of English, ous armed forces. This month we look at the German Williams. Afrikaans, slang and Military in World War II. techno-speak that few 24 A matter of survival outside the military Over the next few months we will be running a series could hope to under- of articles looking at survival, something that has al- stand. Some of the terms ways been important for those in the military. -

Final Vol 25, Body

Stephanie Tara Schwartz / Occupation and 20 ans après: Representing 60 Jewish Dissent in Montreal, 1967-1977 Stephanie Tara Schwartz Occupation and 20 ans après: Representing Jewish Activism in Montreal, 1968-1977 Canadian Jewish Studies / Études juives canadiennes, vol. 25, 2017 61 Two NFB documentaries, Bill Reid’s Occupation (1970) and Jacques Bensimon’s 20 ans après (1977) offer an opportunity to reflect on the diverse politics of Montreal Jews during and following Quebec’s Quiet Revolution. Reading these films together, I argue that Montreal Jewish artists and activists should be considered in relation to the complex local and inter- national politics of postcolonial dissent that marked the late 1960s and early 1970s, and that their experiences defy the narrow confines of a ‘third solitude.’ “Everybody, let’s get upstairs! Let’s take a stand now! Let’s go. EVERYBODY that be- lieves in justice take a stand. Don’t sit on your asses anymore. Move up there and take a stand!” Robert Hubsher uttered these words at Sir George Williams University (SGW) on 20 January 1969, passionately encouraging his peers to join the occupa- tion of the computer room on the ninth floor of the Hall Building in protest of the University administration’s failure to deal appropriately with accusations of racism toward a group of West Indian students from their professor Perry Anderson.1 Fea- tured as an interview subject in Mina Shum’s National Film Board (NFB) documen- tary Ninth Floor (2016), Hubsher explains that being Jewish, his early experiences of antisemitism were a factor in his decision to stand up and support his black peers experiencing racism.