Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

11701-19-A0558 RVH Landmarke 4 Engl

Landmark 4 Brocken ® On the 17th of November, 2015, during the 38th UNESCO General Assembly, the 195 member states of the United Nations resolved to introduce a new title. As a result, Geoparks can be distinguished as UNESCO Global Geoparks. As early as 2004, 25 European and Chinese Geoparks had founded the Global Geoparks Network (GGN). In autumn of that year Geopark Harz · Braunschweiger Land · Ostfalen became part of the network. In addition, there are various regional networks, among them the European Geoparks Network (EGN). These coordinate international cooperation. 22 Königslutter 28 ® 1 cm = 26 km 20 Oschersleben 27 18 14 Goslar Halberstadt 3 2 1 8 Quedlinburg 4 OsterodeOsterodee a.H.a.Ha H.. 9 11 5 13 15 161 6 10 17 19 7 Sangerhausen Nordhausen 12 21 In the above overview map you can see the locations of all UNESCO Global Geoparks in Europe, including UNESCO Global Geopark Harz · Braunschweiger Land · Ostfalen and the borders of its parts. UNESCO-Geoparks are clearly defi ned, unique areas, in which geosites and landscapes of international geological importance are found. The purpose of every UNESCO-Geopark is to protect the geological heritage and to promote environmental education and sustainable regional development. Actions which can infl ict considerable damage on geosites are forbidden by law. A Highlight of a Harz Visit 1 The Brocken A walk up the Brocken can begin at many of the Landmark’s Geopoints, or one can take the Brockenbahn from Wernigerode or Drei Annen-Hohne via Schierke up to the highest mountain of the Geopark (1,141 meters a.s.l.). -

Können Sie Einen Kostenlosen Corona- Schnelltest Durchführen Lassen (Es Empfiehlt Sich Immer, Vorab Telefonisch Oder Per Mail Einen Termin Zu Vereinbaren)

Schnellteststationen Aktuelle Anlaufstellen Hier können Sie einen kostenlosen Corona- Schnelltest durchführen lassen (es empfiehlt sich immer, vorab telefonisch oder per Mail einen Termin zu vereinbaren) Ärzte / Betriebsärzte / Zahnärzte Allgemeinmedizinerin Dr. med. Christine Rose Telefon: 05321 22833 Vititorwall 5, 38640 Goslar Mail: [email protected] Mo-Fr 09:00-10:00 Uhr Allgemeinmediziner Jens Suckstorff Telefon: 05321 8660 Stadtweg 20a, 38644 Goslar Mo-Mi 09:00-12:00 Uhr, Mo 15:00-17:00 Uhr, Di 16:00-18:30 Uhr Do 17:00-19:00 Uhr, Fr 09:00-13:00 Uhr weitere Termine nach Vereinbarung Allgemeinmediziner Dr. A. Eisenhardt Telefon: 05321 8740 Hirschberger Str. 1, 38642 Goslar Mo-Fr 08:30-11:30 Uhr, Mo 17:00-19:00 Uhr Do 15:00-17:00 Uhr Weitere Termine nach Vereinbarung Allgemeinmediziner Niels Gehrmann Telefon: 05321 81959 Feldstr. 36, 38640 Goslar Mo-Fr 08:00-12:00 Uhr Di und Do 15:30-18:00 Uhr Apotheken Apotheke im Marktkauf Dr. Torben Raeth Telefon: 05321 683659 Carl-Zeiss-Str. 4, 38644 Goslar Mail: [email protected] Loewen-Apotheke-Oker Telefon: 05321 65194 Bahnhofstraße 21, 38642 Goslar Mail: [email protected] Jakobi Apotheke Telefon: 05321 23021 Hani Hulwani e.K. Mail: [email protected] Jakobikirchhof 8, 38640 Goslar Am Sa auch bis 14:00 Uhr Niedersachsen Apotheke Mail: [email protected] Rosentorstraße 24, 38640 Goslar Mo/Di/Do/Fr 08:30-18:00 Uhr Mi 08:30-13:00 Uhr, Sa 10:00-13:00 Uhr Bei entsprechenden zeitlichen Möglichkeiten auch ohne Termin Ohlhofer-Apotheke -

Late Jurassic Theropod Dinosaur Bones from the Langenberg Quarry

Late Jurassic theropod dinosaur bones from the Langenberg Quarry (Lower Saxony, Germany) provide evidence for several theropod lineages in the central European archipelago Serjoscha W. Evers1 and Oliver Wings2 1 Department of Geosciences, University of Fribourg, Fribourg, Switzerland 2 Zentralmagazin Naturwissenschaftlicher Sammlungen, Martin-Luther-Universität Halle-Wittenberg, Halle (Saale), Germany ABSTRACT Marine limestones and marls in the Langenberg Quarry provide unique insights into a Late Jurassic island ecosystem in central Europe. The beds yield a varied assemblage of terrestrial vertebrates including extremely rare bones of theropod from theropod dinosaurs, which we describe here for the first time. All of the theropod bones belong to relatively small individuals but represent a wide taxonomic range. The material comprises an allosauroid small pedal ungual and pedal phalanx, a ceratosaurian anterior chevron, a left fibula of a megalosauroid, and a distal caudal vertebra of a tetanuran. Additionally, a small pedal phalanx III-1 and the proximal part of a small right fibula can be assigned to indeterminate theropods. The ontogenetic stages of the material are currently unknown, although the assignment of some of the bones to juvenile individuals is plausible. The finds confirm the presence of several taxa of theropod dinosaurs in the archipelago and add to our growing understanding of theropod diversity and evolution during the Late Jurassic of Europe. Submitted 13 November 2019 Accepted 19 December 2019 Subjects Paleontology, -

Part Two Feudal Institutions

Part Two Feudal Institutions Introduction Amid invasions from abroad and tumult at home, with the decay and near-disappearance of effective government, the men of the early Middle Ages faced a critical problem in supplying their basic social needs-food, protection, companionship. Under such peril ous conditions, the most immediate social unit which could offer support and protection to harassed individuals was the family. What was the nature of the family in early medieval society? This is a question which must be asked in any consideration of the feudal world, but it is surprisingly difficult to answer. Few and uninformative records cast but dim light on this central institution; they are enough to excite our interest but rarely sufficient to give firm responses to our questions. At one time the common view of historians was that the family of the early Middle Ages was characteristically large, extended or patriarchal. Married sons continued to live within their father's house or with one another after their parents' deaths; they sought security against external dangers primarily in their own large numbers. There is, to be sure, much evidence of strong family solidarity and sentiment in medieval society. A heavy moral obli gation, everywhere evident, lay upon family members to avenge the harm done to a kinsman. This is one of the principal themes of FEUDAL INSTITUTIONS the epic poem Raoul of Cambrai (Document 31), as it is of many medieval tales. The characters in it repeatedly assert that warriors who fail to seek vengeance are dastards and cowards, not worth a spur or a glove. -

The Teutonic Order and the Baltic Crusades

Western Oregon University Digital Commons@WOU Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) Department of History 6-10-2019 The eutT onic Order and the Baltic Crusades Alex Eidler Western Oregon University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his Part of the European History Commons, Medieval History Commons, and the Military History Commons Recommended Citation Eidler, Alex, "The eT utonic Order and the Baltic Crusades" (2019). Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History). 273. https://digitalcommons.wou.edu/his/273 This Paper is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at Digital Commons@WOU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Theses, Papers and Projects (History) by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@WOU. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected], [email protected]. The Teutonic Order and the Baltic Crusades By Alex Eidler Senior Seminar: Hst 499 Professor David Doellinger Western Oregon University June 5, 2019 Readers Professor Elizabeth Swedo Professor David Doellinger Copyright © Alex Eidler, 2019 Eidler 1 Introduction When people think of Crusades, they often think of the wars in the Holy Lands rather than regions inside of Europe, which many believe to have already been Christian. The Baltic Crusades began during the Second Crusade (1147-1149) but continued well into the fifteenth century. Unlike the crusades in the Holy Lands which were initiated to retake holy cities and pilgrimage sites, the Baltic crusades were implemented by the German archbishoprics of Bremen and Magdeburg to combat pagan tribes in the Baltic region which included Estonia, Prussia, Lithuania, and Latvia.1 The Teutonic Order, which arrived in the Baltic region in 1226, was successful in their smaller initial campaigns to combat raiders, as well as in their later crusades to conquer and convert pagan tribes. -

Copyrighted Material

33_056819 bindex.qxp 11/3/06 11:01 AM Page 363 Index fighting the Vikings, 52–54 • A • as law-giver, 57–58 Aberfan tragedy, 304–305 literary interests, 56–57 Act of Union (1707), 2, 251 reforms of, 54–55 Adelaide of Saxe-Meiningen, queen of reign of, 50, 51–52 William IV, 268, 361 Alfred, son of King Aethelred, king of Áed, king of Scotland, 159 England, 73, 74 Áed Findliath, ruler in Ireland, 159 Ambrosius Aurelianus (Roman leader), 40 Aedán mac Gabráin, overking of Dalriada, 153 Andrew, Prince, Duke of York (son of Aelfflaed, queen of Edward, king Elizabeth II) of Wessex, 59 birth of, 301 Aelfgifu of Northampton, queen of Cnut, 68 as naval officer, 33 Aethelbald, king of Mercia, 45 response to death of Princess Diana, 313 Aethelbert, king of Wessex, 49 separation from Sarah, Duchess of York, Aethelflaed, daughter of Alfred, king of 309 Wessex, 46 Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, 57, 58, 63 Aethelfrith, Saxon king, 43 Anglo-Saxons Aethelred, king of England, 51, 65–66 appointing an heir, 16 Aethelred, king of Mercia, 45, 46, 55 invasion of Britain, 39–41 Aethelred, king of Wessex, 50 kingdoms of, 37, 42 Aethelstan, king of Wessex, 51, 61–62 kings of, 41–42 Aethelwold, son of Aethelred, king of overview, 12 Wessex, 60 Anna, queen of Scotland, 204 Aethelwulf, king of Wessex, 49 Anne, Princess Royal, daughter of Africa, as part of British empire, 14 Elizabeth II, 301, 309 Agincourt, battle of, 136–138 Anne, queen of England Albert, Prince, son of George V, later lack of heir, 17 George VI, 283, 291 marriage to George of Denmark, 360–361 Albert of -

~~~An!(Qrrhin' Rewa

) ~~w~~ .~~"JJ ) ~~~ an! (Qrrhin' Rewa ,"" Published by The Tennessee Genealogical Society - Quarterly - Mrs. Edwin Miles Standefer, Editor ) VOLUME 16 OCTOBER - DECEMBER 1969 NUMBER 4 LAUDERDALE COUNtY, TENNESSEE ISSUE ) - CONTENTS - THE PRES IDENT I S LETTER. •••• .. .. .. .. • 151 NOTES FROM THE EDITOR I S DESK. • • 152 BOOK REVIEWS. ••• 0 .0 • '. • 153 1878 YELLOW FEVER EPIDEMIC IN MEMPHIS AND SHET..BY CO., TENN. 156 ) 1840 CENSUS OF lAUDERDALE COUNTY," TENNESSEE, ••••• 0 • • 0 •• 161 lAUDERDALE COUNTY MARRIAGE RECORDS, BOOK A (1838-1850). • 163 INDEX TO WILLS, lAUDERDALE COUNn, TENNESSEE. ~ . .. 169 ROANE CO., TENN. - PAUPERS ... .. .. ..-. '. .. eo • ". •• 172 MARRIAGE RECORDS OF SUMNER COUNtY, TENNESSEE 0 •• 177 WEST TENNESSEE DISTRICT, lAND GRANTS, BOOK 1A • . .. 183 QUERIES. NUMBER 69 -182 THROUGH 69-246. ••• .. .. •• 191 ) / ) THE TENNESSEE GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY, POST OFFICE BOX 12124, MEMPHtS, TENN.~8H2 OFFICERS AND STAFF FOR 1969 President Mr. William L. Crawford Vi~e President Mrs•. HenryN. Moore Treasurer Mr. S. caya Phnlips Corresponding Secretary MinJ_ieT. Webb Recording S$Cretary Mrs. Rit~ Young Director of ResE!arch Miss Bernice Cole librarian Mrs. Ro~ l.ollis Cox Advisor Mrs; Lauren~e B. Gardiner Advisor Mrs. Bunyan M. Webb Parliamentarian Mrs. Lois D. Beisch Editor Mrs. Edwin M. Standefer Editorial Staff Miss Bernice Cole Mr. & Mrs. J.MObtey Collinsworth Col. 8tMrs. Bvron G. Hyde Mrs. Gene Davis Mrs. Bunyan M. Webb Mrs. Albert Curl If you are searching for ancestors in Tennessee. remember "Anseatchin' " News the official publication of The Tennessee Genealogical Society. Published quarterly - Annual SUbscription$6.DO All subscriptions begin with first issue of year All subscribers are requested to send· queries for free publication. -

Module Hi1200 Europe, 1000-1250

MODULE HI1200 EUROPE, 1000-1250: WAR, GOVERNMENT AND SOCIETY IN THE AGE OF THE CRUSADES Michaelmas Term Professor Robinson ( 10 ECTS ) CONTENTS 1. Introduction 2 2. A Guide to Module HI1200 3 3. Lecture Topics 6 4. Essay Titles 6 5. Reading List 8 6. Tutorial Assignments 11 1 1. INTRODUCTION This module deals with social and political change in Europe during the two-and-a- half centuries of the development of the crusading movement. It focuses in particular on the internal development of France, Germany, Italy, Spain, Byzantium (the Eastern Christian empire based on Constantinople) and the crusading colonies in the Near East. The most important themes are the development of royal and imperial authority, the structure of aristocratic society, rebellion and the threat of political disintegration, warfare as a primary function of the secular ruling class and the impact of war on the development of European institutions. Module HI1200 is available as an option to Single Honors, Two-Subject Moderatorship and History and Political Science Junior Freshman students. This module is a compulsory element of the Junior Freshman course in Ancient and Medieval History and Culture. The module may also be taken by Socrates students and Visiting students with the permission of the Department of History. Module HI1200 consists of two lectures each week throughout Michaelmas Term, together with a series of six tutorials, for which written assignments are required. The assessment of this module will take the form of: (1) an essay, which accounts for 20% of the over-all assessment of this module and (2) a two-hour examination in Trinity Term, which accounts for 80% of the over-all assessment. -

Germany (1914)

THE MAKING OF THE NATIONS GERMANY VOLUMES ALREADY PUBLISHED IN THIS SERIES FRANCE By Cecil Headlam, m.a. COXTAIXING 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND 16 MAPS AND SMALLER FIGURES IN THE TEXT " It is a sound and readable sketch, which has the signal merit of keeping^ what is salient to the front." British Weekly. SCOTLAND By Prof. Robert S. Rait CONTAINING 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND 11 MAPS AND SMALLER FIGURES IN THE TEXT of "His 'Scotland' is an equally careful piece work, sound in historical fact, critical and dispassionate, and dealing, for the most part, with just those periods in which it is possible to trace a real advance in the national develop- ment."—Athenceum. SOUTH AMERICA By W. H. KoEBEL CONTAINING 32 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS AND 10 MAPS AND SMALLER FIGURES IN THE TEXT " Mr. Koebel has done his work well, and by laying stress on the trend of Governments and peoples rather than on lists of Governors or Presidents, and by knowing generally what to omit, he has contrived to produce a book which meets an obvious need. ' —Morning Post. A. AND C. BLACK, 4 SOHO SQUARE, LONDON, W. AGENTS AMERICA .... THE MACMILLAN COMPANY 64 & 66 FIFTH AVENUE. NEW YORK AUSTEALA8IA . OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS 20- FLINDERS Lane. MELBOURNE CANADA THE MACMILLAN COMPANY OF CANADA. LTD. St. Marti.n's House, 70 Bond street, TORONTO RiDLA MACMILLAN 4 COMPANY, LTD. MACMILLAN BUILDING, BOMBAY 309 Bow Bazaar STREBT, CALCUTTA ^. Rischgits QUEEN LOUISE (lT7G-lS10), WinOW OF FREDERICK -WILLIAM III. OF PRUSSIA. Her patriotism anil self-sacrifice after the disaster of Jena have given her a liigli place in the affections of the German nation. -

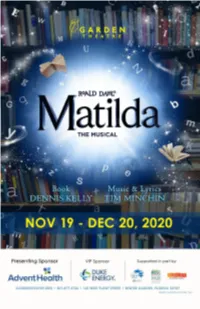

Matilda-Playbill-FINAL.Pdf

We’ve nevER been more ready with child-friendly emergency care you can trust. Now more than ever, we’re taking extra precautions to keep you and your kids safe in our ER. AdventHealth for Children has expert emergency pediatric care with 14 dedicated locations in Central Florida designed with your little one in mind. Feel assured with a child-friendly and scare-free experience available near you at: • AdventHealth Winter Garden 2000 Fowler Grove Blvd | Winter Garden, FL 34787 • AdventHealth Apopka 2100 Ocoee Apopka Road | Apopka, Florida 32703 Emergency experts | Specialized pediatric training | Kid-friendly environments 407-303-KIDS | AdventHealthforChildren.com/ER 20-AHWG-10905 A part of AdventHealth Orlando Joseph C. Walsh, Artistic Director Elisa Spencer-Kaplan, Managing Director Book by Music and Lyrics by Dennis Kelly Tim Minchin Orchestrations and Additional Music Chris Nightingale Presenting Sponsor: ADVENTHEALTH VIP Sponsor: DUKE ENERGY Matilda was first commissioned and produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company and premiered at The Courtyard Theatre, Stratford-upon-Avon, England on 9 November 2010. It transferred to the Cambridge Theatre in the West End of London on 25 October 2011 and received its US premiere at the Shubert Theatre, Broadway, USA on 4 March 2013. ROALD DAHL’S MATILDA THE MUSICAL is presented through special arrangement with Music Theatre International (MTI) All authorized performance materials are also supplied by MTI. 423 West 55th Street, New York, NY 10019 Tel: (212)541-4684 Fax: (212)397-4684 www.MTIShows.com SPECIAL THANKS Garden Theatre would like to thank these extraordinary partners, with- out whom this production of Matilda would not be possible: FX Design Group; 1st Choice Door & Millwork; Toole’s Ace Hardware; Signing Shadows; and the City of Winter Garden. -

Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony

he collection of essays presented in “Devotional Cross-Roads: Practicing Love of God in Medieval Gaul, Jerusalem, and Saxony” investigates test case witnesses of TChristian devotion and patronage from Late Antiquity to the Late Middle Ages, set in and between the Eastern and Western Mediterranean, as well as Gaul and the regions north of the Alps. Devotional practice and love of God refer to people – mostly from the lay and religious elite –, ideas, copies of texts, images, and material objects, such as relics and reliquaries. The wide geographic borders and time span are used here to illustrate a broad picture composed around questions of worship, identity, reli- gious affiliation and gender. Among the diversity of cases, the studies presented in this volume exemplify recurring themes, which occupied the Christian believer, such as the veneration of the Cross, translation of architecture, pilgrimage and patronage, emergence of iconography and devotional patterns. These essays are representing the research results of the project “Practicing Love of God: Comparing Women’s and Men’s Practice in Medieval Saxony” guided by the art historian Galit Noga-Banai, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the histori- an Hedwig Röckelein, Georg-August-University Göttingen. This project was running from 2013 to 2018 within the Niedersachsen-Israeli Program and financed by the State of Lower Saxony. Devotional Cross-Roads Practicing Love of God in Medieval Jerusalem, Gaul and Saxony Edited by Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover Röckelein/Noga-Banai/Pinchover Devotional Cross-Roads ISBN 978-3-86395-372-0 Universitätsverlag Göttingen Universitätsverlag Göttingen Hedwig Röckelein, Galit Noga-Banai, and Lotem Pinchover (Eds.) Devotional Cross-Roads This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.