97 Original Article XI'an DAXUEXI ALLEY MOSQUE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Olympic Cities Chapter 7

Chapter 7 Olympic Cities Chapter 7 Olympic Cities 173 Section I Host City — Beijing Beijing, the host city of the Games of the XXIX Olympiad, will also host the 13th Paralympic Games. In the year 2008, Olympic volunteers, as ambassadors of Beijing, will meet new friends from throughout the world. The Chinese people are eager for our guests to learn about our city and the people who live here. I. Brief Information of Beijing Beijing, abbreviated“ JING”, is the capital of the People’s Republic of China and the center of the nation's political, cultural and international exchanges. It is a famous city with a long history and splendid culture. Some 500,000 years ago, Peking Man, one of our forefathers, lived in the Zhoukoudian area of Beijing. The earliest name of Beijing 174 Manual for Beijing Olympic Volunteers found in historical records is“JI”. In the eleventh century the state of JI was subordinate to the XI ZHOU Dynasty. In the period of“ CHUN QIU” (about 770 B.C. to 477 B.C.), the state of YAN conquered JI, moving its capital to the city of JI. In the year 938 B.C., Beijing was the capital of the LIAO Dynasty (ruling the northern part of China at the time), and for more than 800 years, the city became the capital of the Jin, Yuan, Ming and Qing dynasties. The People’s Republic of China was established on October 1, 1949, and Beijing became the capital of this new nation. Beijing covers more than 16,000 square kilometers and has 16 subordinate districts (Dongcheng, Xicheng, Chongwen, Xuanwu, Chaoyang, Haidian, Fengtai, Shijingshan, Mentougou, Fangshan, Tongzhou, Shunyi, Daxing, Pinggu, Changping and Huairou) and 2 counties (Miyun and Yanqing). -

View / Download 7.3 Mb

Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 ABSTRACT Between Shanghai and Mecca: Diaspora and Diplomacy of Chinese Muslims in the Twentieth Century by Janice Hyeju Jeong Department of History Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Engseng Ho, Advisor ___________________________ Prasenjit Duara, Advisor ___________________________ Nicole Barnes ___________________________ Adam Mestyan ___________________________ Cemil Aydin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy, in the Department of History in the Graduate School of Duke University 2019 Copyright by Janice Hyeju Jeong 2019 Abstract While China’s recent Belt and the Road Initiative and its expansion across Eurasia is garnering public and scholarly attention, this dissertation recasts the space of Eurasia as one connected through historic Islamic networks between Mecca and China. Specifically, I show that eruptions of -

Growth and Decline of Muslim Hui Enclaves in Beijing

EG1402.fm Page 104 Thursday, June 21, 2007 12:59 PM Growth and Decline of Muslim Hui Enclaves in Beijing Wenfei Wang, Shangyi Zhou, and C. Cindy Fan1 Abstract: The Hui people are a distinct ethnic group in China in terms of their diet and Islamic religion. In this paper, we examine the divergent residential and economic develop- ment of Niujie and Madian, two Hui enclaves in the city of Beijing. Our analysis is based on archival and historical materials, census data, and information collected from recent field work. We show that in addition to social perspectives, geographic factors—location relative to the northward urban expansion of Beijing, and the character of urban administrative geog- raphy in China—are important for understanding the evolution of ethnic enclaves. Journal of Economic Literature, Classification Numbers: O10, I31, J15. 3 figures, 2 tables, 60 refer- ences. INTRODUCTION esearch on ethnic enclaves has focused on their residential and economic functions and Ron the social explanations for their existence and persistence. Most studies do not address the role of geography or the evolution of ethnic enclaves, including their decline. In this paper, we examine Niujie and Madian, two Muslim Hui enclaves in Beijing, their his- tory, and recent divergent paths of development. While Niujie continues to thrive as a major residential area of the Hui people in Beijing and as a prominent supplier of Hui foods and services for the entire city, both the Islamic character and the proportion of Hui residents in Madian have declined. We argue that Madian’s location with respect to recent urban expan- sion in Beijing and the administrative geography of the area have contributed to the enclave’s decline. -

An Ancient Mosque in Ningbo, China “Historical and Architectural Study”

JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE P-ISSN: 2086-2636 E-ISSN: 2356-4644 Journal Home Page: http://ejournal.uin-malang.ac.id/index.php/JIA AN ANCIENT MOSQUE IN NINGBO, CHINA “HISTORICAL AND ARCHITECTURAL STUDY” |Received December 13th 2016 | Accepted April 4th 2017| Available online June 15th 2017| | DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.18860/jia.v4i3.3851 | Hamada M. Hagras ABSTRACT Faculty of Archaeology, Fayoum University, Fayoum, Egypt With the rise of Tang dynasty (618–907), Ningbo was an important [email protected] commercial city on the Chinese eastern coast. Arab merchants had an important role in trade relations between China and the West. Ningbo mosque was initially built in 1003 during Northern Song period by Muslims traders who had migrated from Arab lands to settle in China. Through ongoing research of representative Muslim architecture, such as Chinese Mosques, this paper seeks to shed light on the artistic features of this mosque. Many of the key characteristics of this distinctive ethnic heritage are based on commonly held religious beliefs and on the relationship between culture and religion. This paper aims to study the characteristics of Chinese mosques architecture, through studying one of the most important planning patterns of the traditional courtyards plan Known as Siheyuan, and it will also make a practical study on Ningbo Yuehu Mosque. The result of this study shows that the Ningbo Yuehu mosque is like Chinese mosques which follows essentially the norms of Chinese planning, layout design, and wooden structures. KEYWORDS: Ningbo, Mosque, Plan, Courtyard, Inscriptions INTRODUCTION (626‐649) received an embassy from the last Sassanid rulers Yazdegerd III (631‐651) asking for help against WHY THE SELECTED NINGBO MOSQUE? the invading Arab armies of his country, however, the emperor avoid to help him to ward off problems that Although many Chinese cities contain more may result from it [8][9]. -

The Floating Community of Muslims in the Island City of Guangzhou

Island Studies Journal, 12(2), 2017, pp. 83-96 The floating community of Muslims in the island city of Guangzhou Ping Su Sun Yat-sen University, Zhuhai, China [email protected] ABSTRACT: The paper explores how Guangzhou’s urban density and hub functions have conditioned its cultural dynamics by looking specifically at the city’s Muslim community. Guangzhou’s island spatiality has influenced the development of the city’s Muslim community both historically and in the contemporary era. As a historic island port city, Guangzhou has a long-standing tradition of commerce and foreign trade, which brought to the city the first group of Muslims in China. During the Tang and Song dynasties, a large Muslim community lived in the fanfang of Guangzhou, a residential unit designated by the government for foreigners. Later, in the Ming and Qing dynasties, Hui Muslims from northern China, who were mostly soldiers, joined foreign Muslims in Guangzhou to form an extended community. However, during the Cultural Revolution, Guangzhou’s Muslim community and Islamic culture underwent severe damage. It was not until China’s period of reform and opening-up that the Muslim community in Guangzhou started to revive, thanks to the city’s rapid economic development, especially in foreign trade. This is today a floating community, lacking geographical, racial, ethnic, and national boundaries. This paper argues that Guangzhou’s island spatiality as a major port at the mouth of the Pearl River has given rise to a floating Muslim community. Keywords: floating community, Guangzhou, island cities, Muslims, trading port, spatiality https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.18 © 2017 – Institute of Island Studies, University of Prince Edward Island, Canada. -

The Spreading of Christianity and the Introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949)

Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid Programa de doctorado en Concervación y Restauración del Patrimonio Architectónico The Spreading of Christianity and the introduction of Modern Architecture in Shannxi, China (1840-1949) Christian churches and traditional Chinese architecture Author: Shan HUANG (Architect) Director: Antonio LOPERA (Doctor, Arquitecto) 2014 Tribunal nombrado por el Magfco. y Excmo. Sr. Rector de la Universidad Politécnica de Madrid, el día de de 20 . Presidente: Vocal: Vocal: Vocal: Secretario: Suplente: Suplente: Realizado el acto de defensa y lectura de la Tesis el día de de 20 en la Escuela Técnica Superior de Arquitectura de Madrid. Calificación:………………………………. El PRESIDENTE LOS VOCALES EL SECRETARIO Index Index Abstract Resumen Introduction General Background........................................................................................... 1 A) Definition of the Concepts ................................................................ 3 B) Research Background........................................................................ 4 C) Significance and Objects of the Study .......................................... 6 D) Research Methodology ...................................................................... 8 CHAPTER 1 Introduction to Chinese traditional architecture 1.1 The concept of traditional Chinese architecture ......................... 13 1.2 Main characteristics of the traditional Chinese architecture .... 14 1.2.1 Wood was used as the main construction materials ........ 14 1.2.2 -

What Knowledge Is Sought in China? Arab Visitors and Chinese Propaganda Dhul Hijjah, 1440 - August 2019

48 Dirasat What Knowledge Is Sought in China? Arab Visitors and Chinese Propaganda Dhul Hijjah, 1440 - August 2019 Kyle Haddad - Fonda What Knowledge Is Sought in China? Arab Visitors and Chinese Propaganda Kyle Haddad - Fonda 4 Dirasat No. 48 Dhul Hijjah, 1440 - August 2019 © King Faisal Center for Research and Islamic Studies, 2019 King Fahd National Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data Haddad Fonda, Kyle What Knowledge Is Sought in China: Arab Visitors and Chinese Propaganda. / Haddad Fonda, Kyle.- Riyadh, 2019 48 p ; 23 x 16.5 cm ISBN: 978-603-8268-23-0 1- Propaganda, Chinese I-Title 303.3750951 dc 1440/11524 L.D. no. 1440/11524 ISBN: 978-603-8268-23-0 Table of Contents Abstract 6 The standard itinerary in the 1950s 10 The Standard Itinerary up to 2018 17 Since the Crackdown 31 Can China’s Arab Outreach Be Successful? 35 5 6 Dirasat No. 48 Dhul Hijjah, 1440 - August 2019 Abstract This article investigates the experiences of Arab dignitaries, journalists, youth groups, and trade envoys who have visited the People’s Republic of China in an official or semiofficial capacity since China’s initial overtures to Middle Eastern countries in 1955. First, it outlines the “standard itineraries” given to Arab delegations touring China both in the 1950s and in the twenty- first century, demonstrating how the changes to this agenda reflect the shifting priorities of the Chinese state. Second, it explores how the Chinese government has refined the vision of Chinese Islam that it presents to visitors from the Middle East, taking into account Beijing’s changing attitude toward expressions of Islamic piety. -

IN the MINORITY Holding on to Ethnic Identity in a Changing Beijing

IN THE MINORITY Holding on to Ethnic Identity in a Changing Beijing Follow us on WeChat Now Advertising Hotline 400 820 8428 城市漫步北京 英文版 6 月份 国内统一刊号: CN 11-5232/GO China Intercontinental Press ISSN 1672-8025 JUNE 2016 主管单位 :中华人民共和国国务院新闻办公室 Supervised by the State Council Information Office of the People's Republic of China 主办单位 :五洲传播出版社 地址 :北京市海淀区北三环中路31 号生产力大楼 B 座 602 邮编 100088 B-602 Shengchanli Building, No. 31 Beisanhuan Zhonglu, Haidian District, Beijing 100088, PRC http://www.cicc.org.cn 总编辑 Editor in Chief 慈爱民 Ci Aimin 期刊部负责人 Supervisor of Magazine Department 邓锦辉 Deng Jinhui 编辑 Editor 朱莉莉 Zhu Lili 发行 / 市场 Distribution / Marketing 黄静,李若琳 Huang Jing, Li Ruolin Editor-in-Chief Oscar Holland Food & Drink Editor Noelle Mateer Staff Reporter Dominique Wong National Arts Editor Andrew Chin Digital Content Editor Justine Lopez Designers Li Xiaoran, Iris Wang Staff Photographer Holly Li Contributors Mia Li, Zoey Zha, Virginia Werner, Jens Bakker, Emma Huang, Aelred Doyle, Dominic Ngai, Tongfei Zhang Urbanatomy Media Shanghai (Head office) 上海和舟广告有限公司 上海市蒙自路 169 号智造局 2 号楼 305-306 室 邮政编码 : 200023 Room 305-306, Building 2, No.169 Mengzi Lu, Shanghai 200023 电话 : 021-8023 2199 传真 : 021-8023 2190 (From February 13) Beijing 广告代理 : 上海和舟广告有限公司 北京市东城区东直门外大街 48 号东方银座 C 座 9G 邮政编码 : 100027 48 Dongzhimenwai Dajie Oriental Kenzo (Ginza Mall) Building C Room 9G, Dongcheng District, Beijing 100027 电话 : 010-8447 7002 传真 : 010-8447 6455 Guangzhou 上海和舟广告有限公司广州分公司 广州市越秀区麓苑路 42 号大院 2 号楼 610 房 邮政编码 : 510095 Room 610, No. 2 Building, Area 42, Lu Yuan Lu, Yuexiu District, -

Stars Over Beijing Seven Courses, Six Maestros, Five Stars One Night Only

北京爱见达广告DM NOV 4-NOV 17 北京爱见达广告有限公司 京工商印广登字 20080072 号 ISSUE 66, THU-WED 北京市朝阳区建国路 93 号 10 号楼 2801 室 2010 年第 20 期 DINING . SHOPPING . NIGHTLIFE Stars Over Beijing Seven Courses, Six Maestros, Five Stars One Night Only Managing the dragon Mixing business with pleasure Business lunches Halal cuisine 广告征订热线 5820 7700 PLUS VISITOR INFORMATION, CULTURAL EVENTS, MUSIC, SPORTS, STAGE & CINEMA 广告DM THU, NOV 4 – WED, NOV 17 AGENDA 1 编制:北京爱见达广告有限公司 Editorial Planning Manager Jennifer Thomé Assistant Editorial Planning Jiang Jun Visual Planning Joey Guo Art Director Susu Luo Photographers Shelley Jiang, Sui, Judy Zhou Contributors Steven Schwankert, Marla Fong, Dan Edwards, Emmet Conlon O’Reilly, Sarah Lavers 广告总代理:深度体验国际广告(北京)有限公司 Advertising Agency: Immersion International Advertising (Beijing) Co., Limited 广告热线:5820 7700 Designers Yuki Jia, Helen He, Li Xing, Li Yang Distribution Jenny Wang, Victoria Wang Marketing Skott Taylor, Cindy Kusuma, Cao Yue, Lyn Zhao Sales Manager Elena Damjanoska Account Executives Lynn Cui, Sally Fang, Gloria Hao, Phoebe Li, Vincent Liu, Maggie Qi, Maggie Sun, Jackie Yu, Sophia Zhou Inquiries Listings: [email protected] Distribution: [email protected] Sales: [email protected] Marketing: [email protected] Sales Hotline: (010) 5820 7700 Cover image: Hilton Beijing Wangfujing. 2 AGENDA THU, NOV 4 – WED, NOV 17 广告DM CONTENTS Thu, Nov 4 - Wed, Nov 17 14 16 18 54 SPOTLIGHTS Mosques ...............................................................................56 Nils-Arne Schroeder .....................................................12 -

Beijing Sic 4H3m

4 Hari 3 Malam Beijing SIC ATURCARA LAWATAN HARI 01 KETIBAAN BEIJING (SP/MT/MM) Ketibaan di lapangan terbang Beijing (ketibaan hari Khamis). Dihantar ke hotel untuk daftar masuk. Selepas sarapan, lawatan ke National Theatre, Tiananmen Square, Forbidden City, dan selepas makan malam, dibawa untuk menyaksikan persembahan Acrobatic Show. Hotel: Odin Hotel atau setaraf HARI 02 BEIJING (SP/MT/MM) Selepas sarapan, lawatan ke Juyongguan Great Wall, bergambar di Olympic Stadium Bird Nest dan membeli-belah di Wangfujing Street. Hotel: Odin Hotel atau setaraf HARI 03 BEIJING (SP/MT/MM) Selepas sarapan, Lawatn ke The Summer Palace, Niujie Mosque dan Muslim Supermarket, The Place, sebuah pusat membeli-belah yang dihiasi dengan skrin LED. Hotel: Odin Hotel atau setaraf HARI 04 PERLEPASAN BEIJING (SP/MT/MM) Selepas sarapan, daftar keluar hotel. Membeli-belah di Qianmen Walk Street, Nandouya Mosque, Xiushui Market. Selepas makan malam, bertolak ke lapangan terbang untuk penerbangan pulang ke Kuala Lumpur. * Kedai Hentian Wajib (45 minit): Jewellery, Jade, Tea, Silk, Latex, Baoshutang (krim luka terbakar). * Aturcara lawatan dibuat berpandukan penerbangan dengan Malaysia Airlines atau AirAsia. * Ingatan: Aturcara lawatan adalah tentatif sahaja dan tertakluk pada perubahan mengikut masa penerbangan anda. Sebarang perubahan akan dibuat oleh pengiring pelancong semasa lawatan mengikut kesesuaian pengalaman mereka. HARGA LAWATAN PER SEORANG (RINGGIT MALAYSIA) DEWASA KANAK-KANAK Min per Berdua Seorang Dengan Katil Tanpa Katil Lawatan 820 TBA 820 N/A Min 4 * Had umur kanak-kanak dengan katil tambahan 6-11 tahun, tanpa katil 2-5 tahun sahaja * Tidak semua hotel ada katil tambahan, tiada katil bermaksud tiada sarapan. * Bayi di bawah umur 2 tahun adalah percuma. -

Resources for the Study of Islamic Architecture Historical Section

RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION Prepared by: Sabri Jarrar András Riedlmayer Jeffrey B. Spurr © 1994 AGA KHAN PROGRAM FOR ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE RESOURCES FOR THE STUDY OF ISLAMIC ARCHITECTURE HISTORICAL SECTION BIBLIOGRAPHIC COMPONENT Historical Section, Bibliographic Component Reference Books BASIC REFERENCE TOOLS FOR THE HISTORY OF ISLAMIC ART AND ARCHITECTURE This list covers bibliographies, periodical indexes and other basic research tools; also included is a selection of monographs and surveys of architecture, with an emphasis on recent and well-illustrated works published after 1980. For an annotated guide to the most important such works published prior to that date, see Terry Allen, Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography. Cambridge, Mass., 1979 (available in photocopy from the Aga Khan Program at Harvard). For more comprehensive listings, see Creswell's Bibliography and its supplements, as well as the following subject bibliographies. GENERAL BIBLIOGRAPHIES AND PERIODICAL INDEXES Creswell, K. A. C. A Bibliography of the Architecture, Arts, and Crafts of Islam to 1st Jan. 1960 Cairo, 1961; reprt. 1978. /the largest and most comprehensive compilation of books and articles on all aspects of Islamic art and architecture (except numismatics- for titles on Islamic coins and medals see: L.A. Mayer, Bibliography of Moslem Numismatics and the periodical Numismatic Literature). Intelligently organized; incl. detailed annotations, e.g. listing buildings and objects illustrated in each of the works cited. Supplements: [1st]: 1961-1972 (Cairo, 1973); [2nd]: 1972-1980, with omissions from previous years (Cairo, 1984)./ Islamic Architecture: An Introductory Bibliography, ed. Terry Allen. Cambridge, Mass., 1979. /a selective and intelligently organized general overview of the literature to that date, with detailed and often critical annotations./ Index Islamicus 1665-1905, ed. -

Searchable PDF Format

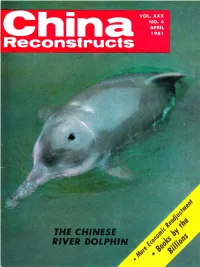

Forest Scene in the Tianshan Mountains. He Chongyuun & '{&f; *" t\U PUBIISHED MoNTHIY .l!!-.ENq!J-S.E--EBEI!9!. !!4!lsH, ARABlc, GERMAN, PoRIUGUESE AND cHlNEsE BY rHE cHtNA wEI-FARE rNsnruTE lsooNc 'cHtNG i.lxG,--cilfinrriii.rf Articles the /trtontft vot. xxx No. I APR![ r98t Reqdjusting Chins'c CONTENTS Economy Xue Muqioo, the well- Economic/Sociol known economist, discusses Xue Muqiao Economic whys ond wherefores ond on Fleadiustment 7 prospects economic- China's Mineral Besources of co. 62 operotion with foreign More Jobs for Spare Labor in Communes 32 countries. Poge 7 Now They Are Cooking with Gas 40 Visit to a Solar Village 42 Low History's Judgment, New Beginning 28 BookslArtsi Educotion Billions of Books Billions of Books .19 Selected Writings of Zhou Enlai 23 Chino printed oyel A Chinese Painter Who Works Abroad 24 1.5 billion books in Design School with Detinite ldeas 34 1980. Who is pub- Education Notes 6 lishing whot? Ihe most-reod titles ond NotionolitieslReligion much other in{ormo. Three Ways to Beautify a Costume tion. Poge t9 of the Miao, Dong and Bouyei Women 46 Tibetan-Art Opera-An Age-Old Art Revlved 50 History's Judgment, New Beginning After Seeing the Opera "Maiden Langsha" 52 National-Style Musical lnstruments 65 The sentences on Jiong Oing <ind nine other defend- What ls China's Policy Towards Religion? 54 o sed o grievo the history o qnd helped new period SciencelMedicine/Archoeotogy o unity, demo ty ond so- First River Dolphin in Captivity 4 c tion. Poge 28 Basic Facts about China's Medical Work 69 First Ramapithecus Skult Found in Yunnan Dig 6B The Chongjiong Sports (Yongtre) Dolphin Physical Culture Research and Sports Medicine 44 Across the Lond Describes o rore fresh- 'The woter voriety of this Zhenjiang: Foremost Landscape under Heaven, 11 foscinoting ocquotic Biggest Crystal of Cinnabar 18 mommol ond Qi Qi, the New Ring Road Aids Beijing Traffic 30 first coptive specimen.