1 Submission to the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As at 28 February 2017

as at 01 M a rch 2017 FESTINA LENTE ADVANCING HUMAN RIGHTS, ACCOUNTABILITY, RECONCILIATION AND GOOD GOVERNANCE IN SRI LANKA January 2015 – March 2017 1 STEP OBSERVATIONS DATE MARCH 2017 Land release The Air Force released 42 acres of private land to the Mullaitivu GA, ending the protests staged by 01 people in front of the Air Force Base since January 2017. March FEBRUARY 2017 Cabinet of Ministers approves compensation Compensation payments proposed by the Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement 28 payments to those affected and Hindu Religious Affairs, as per the Commission appointed to investigate into the incidents, February by Incidents in Welikada approved by Cabinet. Compensation payments approved for 16 prisoners who passed away (Rs. Prison on 9 November 2012 2,000,000.00 each); and 20 injured (Rs. 500,000.00 each) Examination of Sri Lanka’s Sri Lanka’s 8th Periodic Report under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of 22 Report to CEDAW Discrimination Against Women examined by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination February Against Women (CEDAW) Legislation to give effect to The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Bill 09 the International Convention was published in the Government Gazette February for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced English: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_E.pdf Disappearance Sinhala: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_S.pdf Tamil: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_T.pdf -

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

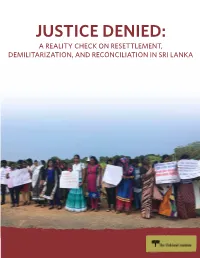

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

In the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for a mandate in the nature of Writ of Certiorari and Prohibition in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution CA (Writ) Application No: 148 /2012 J. M. Lakshman Jayasekara Director General, National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor, Sethsiti paya, Battaramulla. PETITIONER 1. S.M.Gotabaya Jayarathne, Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla. 1st RESPONDENT 1.A P.H.L. Wimalasiri Perera Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla Present Secretary ADDED 1A RESPONDENT 2. Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Chairman, 3. Palitha Kumarasinghe P.C, Member, 4. Mrs. Sirimavo A. Wijayaratne, Member, 5. Ananda Seneviratne, Member 6. N.H. Pathirana, Member, 7. S. Thillanadarajah, Member, 8. M.B.W. Ariyawansa, Member, 9. M.A.Mohomed Nahiya, Member, 10. P.M.L.C. Seneviratne Secretary, All of Public Services Commission, 177, Nawala Road, Colombo 5. 11. Attorney General Attorney General's department, Colombo 12. 12. Hon. Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne Ministry of Buddha Sasana & Religious Affairs 13. Hon. Ratnasiri Wickramanayake Ministry of Good Governance & Infrastructure Facilities 14. Hon. D. E. W. Gunasekera Ministry of Human Resources 15. Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Ministry of Rural Affairs 16. Hon. P. Dayaratne Ministry of Food Security 17. Hon. A. H. M. Fowzie Ministry of Urban Affairs 18. Hon. S. B. Navinne Ministry of Consumer Welfare 19. Hon. Piyasena Gamage Ministry of National Resources 20. Hon. (Prof) Tissa Vitharana Ministry of Scientific Affairs 21. -

REFUGEECOSATT3.Pdf

+ + + Refugees and IDPs in South Asia Editor Dr. Nishchal N. Pandey + + Published by Consortium of South Asian Think Tanks (COSATT) www.cosatt.org Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) www.kas.de First Published, November 2016 All rights reserved Printed at: Modern Printing Press Kathmandu, Nepal. Tel: 4253195, 4246452 Email: [email protected] + + Preface Consortium of South Asian Think-tanks (COSATT) brings to you another publication on a critical theme of the contemporary world with special focus on South Asia. Both the issues of refugees and migration has hit the headlines the world-over this past year and it is likely that nation states in the foreseeable future will keep facing the impact of mass movement of people fleeing persecution or war across international borders. COSATT is a network of some of the prominent think-tanks of South Asia and each year we select topics that are of special significance for the countries of the region. In the previous years, we have delved in detail on themes such as terrorism, connectivity, deeper integration and the environment. In the year 2016, it was agreed by all COSATT member institutions that the issue of refugees and migration highlighting the interlinkages between individual and societal aspirations, reasons and background of the cause of migration and refugee generation and the role of state and non-state agencies involved would be studied and analyzed in depth. It hardly needs any elaboration that South Asia has been both the refugee generating and refugee hosting region for a long time. South Asian migrants have formed some of the most advanced and prosperous diasporas in the West. -

Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate Jyotsna Shankar Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate Jyotsna Shankar Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Shankar, Jyotsna, "Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 201. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/201 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE POST-CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION IN SRI LANKA AND CYPRUS: AVOIDING A STALEMATE SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR BILL ASCHER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY JYOTSNA SHANKAR FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL-SPRING/2010-2011 APRIL 12, 2011 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS .............................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER ONE: GOALS ......................................................................................... 4 SRI LANKA ................................................................................................................. 4 CYPRUS .................................................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND AND TRENDS ................................................... 19 -

Transitional Justice Reconciliation Good Governance Resettlement

Transitional Reconciliation Justice Resettlement Good and Durable Governance Solutions SRI LANKA PEACEBUILDING PRIORITY PLAN August 2016 Overview and Strategic Objective The Peacebuilding Priority Plan (PPP) supports the Government of Sri Lanka to implement its reconciliation and accountability/transitional justice commitments to its people as part of its peacebuilding agenda. The three (3) year comprehensive plan builds on the Government’s ongoing political reforms and the Human Rights Council Resolution of September 2016 which Sri Lanka co- sponsored. The United Nations has been tasked to play a key role in developing and coordinating the implementation of the plan that will also serve as a key tool for coordinating development partners’ support to peacebuilding. The Government of Sri Lanka has put in place institutional structures to deliver on various peacebuilding commitments, with the Secretariat for Coordination of Reconciliation Mechanisms (SCRM) in the Prime Minister Office having the central coordination function. Operationalization of the Plan is guided by the Government’s four (4) Pillars of support of: Transitional Justice; Reconciliation; Good Governance; and Resettlement and Durable Solutions. Funding for the plan will come from various sources including UN, development partners and Government sources. The UN Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) will be strategically positioned to catalyse and leverage the peacebuilding support efforts. Sri Lanka Peacebuilding Priority Plan - Funding Summary Of which: PBF Government Pillar/Strategic Funding Funding Focus Area(s) outcome Need Committed Pledged Gap3 through IRF1 2016 1. Transitional Justice Outcome: 1. Capacity and consultations 2. Truth Telling Government leads a credible, victim- centric process of accountability, 3. Office of Missing Persons 2 2 2 truth-seeking, reparations for past $15.8 $2.7 $2.3 $10.9 4. -

Select Committee Report

PARLIAMENTARY SERIES NO. 281 OF The Seventh Parliament of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka (First Session) REPORT OF SELECT COMMITTEE OF PARLIAMENT TO DISCUSS THE HEADS OF EXPENDITURE OF MINISTRIES SELECTED FROM THE BUDGET ESTIMATES OF 2014 Presented by Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva Chairman of the Committee Ordered by the Parliament of Sri Lanka to be printed on 14 December 2013 PRINTED AT THE DEPARTMENT OF GOVERNMENT PRINTING, SRI LANKA TO BE PURCHASED AT THE GOVERNMENT PUBLICATIONS BUREAU, COLOMBO Select Committee to discuss the Heads of Expenditure of Ministries selected from the Budget Estimates of 2014 Committee: Hon. Nimal Siripala de Silva (Chairman) Hon. W. D. J. Senewiratne Hon. (Dr.) Sarath Amunugama Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena Hon. Rauf Hakeem Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Hon. Chandrasiri Gajadeera Hon. Muthu Sivalingam Hon. Lasantha Alagiyawanna Hon. M. Joseph Michael Perera Hon. John Amaratunga Hon. Sunil Handunnetti Hon. Suresh K. Premachandran Hon. Pon. Selvarasa Hon. R. Yogarajan Hon. Akila Viraj Kariyawasam Hon. Silvastrie Alantin Hon. (Dr.) Harsha De Silva Hon. (Dr.) (Mrs.) Sudarshini Fernandopulle Hon. (Mrs.) Rosy Senanayake Hon. Hunais Farook ( 2 ) REPORT The following motion moved by the Leader of the House of Parliament on 22 November 2013 was approved by the House. The Leader of the House of Parliament,— Select Committee of Parliament to discuss the Heads of Expenditure of the Ministries selected from the Budget Estimates of the year 2014,— Whereas the period of time allocated to the Committee stage programme -

EB PMAS Class 2 2011 2.Pdf

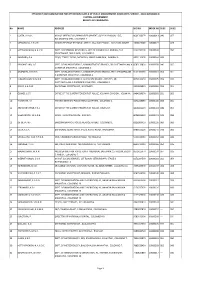

EFFICIENCY BAR EXAMINATION FOR OFFICERS IN CLASS II OF PUBLIC MANAGEMENT ASSISTANT'S SERVICE - 2011(II)2013(2014) CENTRAL GOVERNMENT RESULTS OF CANDIDATES No NAME ADDRESS NIC NO INDEX NO SUB1 SUB2 1 COSTA, K.A.G.C. M/Y OF DEFENCE & URBAN DEVELOPMENT, SUPPLY DIVISION, 15/5, 860170337V 10000013 040 057 BALADAKSHA MW, COLOMBO 3. 2 MEDAGODA, G.R.U.K. INLAND REVENUE REGIONAL OFFICE, 334, GALLE ROAD, KALUTARA SOUTH. 745802338V 10000027 --- 024 3 HETTIARACHCHI, H.A.S.W. DEPT. OF EXTERNAL RESOURCES, M/Y OF FINANCE & PLANNING, THE 823273010V 10000030 --- 050 SECRETARIAT, 3RD FLOOR, COLOMBO 1. 4 BANDARA, P.A. 230/4, TEMPLE ROAD, BATAPOLA, MADELGAMUWA, GAMPAHA. 682113260V 10000044 ABS --- 5 PRASANTHIKA, L.G. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATIVE BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM A 858513383V 10000058 040 055 GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 6 ATAPATTU, D.M.D.S. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ADMINISTRATION BRANCH, SRI CHITTAMPALAM 816130069V 10000061 054 051 A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 7 KUMARIHAMI, W.M.S.N. DEPT. OF INLAND REVENUE, ACCOUNTS BRANCH, POB 515, SRI 867010025V 10000075 059 070 CHITTAMPALAM A GARDINER MAWATHA, COLOMBO 2. 8 JENAT, A.A.D.M. DIVISIONAL SECRETARIAT, NEGOMBO. 685060892V 10000089 034 051 9 GOMES, J.S.T. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA DIVISION, KELANIYA. 846453857V 10000092 031 052 10 HARSHANI, A.I. FINANCE BRANCH, POLICE HEAD QUARTERS, COLOMBO 1. 827122858V 10000104 064 061 11 ABHAYARATHNE, Y.P.J. OFFICE OF THE SUPERINTENDENT OF POLICE, KELANIYA. 841800117V 10000118 049 057 12 WEERAKOON, W.A.D.B. 140/B, THANAYAM PLACE, INGIRIYA. 802893329V 10000121 049 068 13 DE SILVA, W.I. -

In!Sri!Lanka!

[NAME] [FIRM] [ADDRESS] [TELEPHONE NUMBER] [FAX NUMBER] UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE EXECUTIVE OFFICE FOR IMMIGRATION REVIEW IMMIGRATION COURT [CITY, STATE] __________________________________________ ) In the Matter of: ) ) File No.: A __________ __________ ) ) In removal proceedings ) __________________________________________) INDEX TO DOCUMENTATION OF COUNTRY CONDITIONS REGARDING PERSECUTION OF HIV-POSITIVE INDIVIDUALS IN SRI LANKA TAB SUMMARY GOVERNMENTAL SOURCES 1 U.S. Dep’t. of State, Sri Lanka 2019 Human Rights Report (2020), available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/SRI-LANKA-2019-HUMAN- RIGHTS-REPORT.pdf • “Persons who provided HIV prevention services and groups at high risk of infection reportedly suffered discrimination. In addition, hospital officials reportedly publicized the HIV-positive status of their patients and occasionally refused to provide health care to HIV-positive persons.” (p. 25) • “The constitution prohibits discrimination, including with respect to employment and occupation, on the basis of race, religion, language, caste, sex, political opinion, or place of birth. The law does not prohibit employment or occupational discrimination on the basis of color, sexual orientation or gender identity, age, HIV-positive status, or status with regard to other communicable diseases.” (p. 28) 2 U.S. Dep’t. of State, Sri Lanka 2018 Human Rights Report (2019), available at: https://www.state.gov/wp-content/uploads/2019/03/SRI-LANKA-2018.pdf TAB SUMMARY • “Persons who provided HIV prevention services and groups at high risk of infection reportedly suffered discrimination.” (p. 21) • “[H]ospital officials reportedly publicized the HIV-positive status of their clients and occasionally refused to provide health care to HIV-positive persons.” (p. -

2014 Human Rights Report

SRI LANKA 2014 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sri Lanka is a constitutional, multi-party republic. Votes re-elected President Mahinda Rajapaksa to a second six-year term in 2010. Parliament, elected in 2010, shares constitutional power with the president. President Rajapaksa’s family dominated government. Two of President Rajapaksa’s brothers held key executive branch posts, as defense secretary and economic development minister, and a third brother was the speaker of Parliament. A large number of the President Rajapaksa’s other relatives, including his son, also served in important political and diplomatic positions. Independent observers generally characterized the presidential, parliamentary, and local elections as problematic. The 2010 elections were fraught with election law abuses by all major parties, especially the governing coalition’s use of state resources for its own advantage. Authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. The major human rights problems reported over the year were: attacks on, and harassment of, civil society activists, journalists, and persons viewed as sympathizers of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) by individuals allegedly tied to the government; involuntary disappearances, arbitrary arrest and detention, torture, abuse of detainees, rape, and other forms of sexual and gender- based violence committed by police and security forces; and widespread impunity for a broad range of human rights abuses. Involuntary disappearances and unlawful killings continued to diminish in comparison with the immediate postwar period. Nevertheless, harassment, threats, and attacks by progovernment loyalists against media institutions, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), and critics of the government were prevalent, contributing to widespread fear and self- censorship by journalists and diminished democratic activity due to the general failure to prosecute perpetrators. -

Sri Lanka 2015 Human Rights Report

SRI LANKA 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sri Lanka is a constitutional, multiparty republic with a freely elected government. Rejecting the re-election bid of Mahinda Rajapaksa, in January voters elected President Maithripala Sirisena to a five-year term. Parliament, elected in August, shares constitutional power with the president. The EU Election Observation Mission characterized the August parliamentary elections as the “most peaceful and efficiently conducted elections in the country’s recent history.” Although polling was free and fair, the former Rajapaksa government utilized state resources for its own advantage during the presidential election campaign. Civilian authorities maintained effective control over the security forces. In steps designed to enhance national unity following years of civil war, on August 29, the government closed the Omanthai military checkpoint, which previously divided government-held territory from former Liberation Tiger of Tamil Eelam (LTTE)-controlled territory. In March the government adopted the constitution’s 19th amendment, which limits the powers of the presidency and begins a process of restoring the independence of government commissions. In September the government cosponsored a resolution on human rights at the UN Human Rights Council and welcomed visits by the UN special rapporteur on transitional justice, the UN Working Group on Enforced and Involuntary Disappearances, and the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) Office of Legal Affairs team. The president established the Office of National Unity and Reconciliation to play a key role in the government’s reconciliation efforts. Following the August parliamentary elections, the government established the Ministry of National Dialogue to further advance the government’s reconciliation initiatives. -

Sri Lanka 2016 Human Rights Report

SRI LANKA 2016 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Sri Lanka is a constitutional, multiparty republic with a freely elected government. In January 2015, voters elected President Maithripala Sirisena to a five-year term. The Parliament shares power with the president. August 2015 parliamentary elections resulted in a coalition government between the two major political parties. Both elections were free and fair. Civilian authorities generally maintained effective control over the security forces; however, there were continued reports that police and security forces sometimes acted independently. The most significant human rights problems were incidents of arbitrary arrest, lengthy detention, surveillance, and harassment of civil society activists, journalists, members of religious minorities, and persons viewed as sympathizers of the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE). Other human rights problems included abuse of power and reports of torture by security services. Severe prison overcrowding and lack of due process remained problems, as did some limits on freedoms of assembly and association, corruption, physical and sexual abuse of women and children, and trafficking in persons. Discrimination against women, persons with disabilities, and persons based on sexual orientation continued, and limits on workers’ rights and child labor also remained problems. Impunity for crimes committed during and following the armed conflict continued, particularly in cases of killings, torture, sexual violence, corruption, and other human rights abuses. The government made incremental progress on addressing impunity for violations of human rights. The government took some steps to arrest and detain a limited number of military, police, and other officials implicated in old and new cases, including the killing of parliamentarians and the abductions and suspected killings of journalists and private citizens.