CCPR Recommendations by CPA.Docx

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As at 28 February 2017

as at 01 M a rch 2017 FESTINA LENTE ADVANCING HUMAN RIGHTS, ACCOUNTABILITY, RECONCILIATION AND GOOD GOVERNANCE IN SRI LANKA January 2015 – March 2017 1 STEP OBSERVATIONS DATE MARCH 2017 Land release The Air Force released 42 acres of private land to the Mullaitivu GA, ending the protests staged by 01 people in front of the Air Force Base since January 2017. March FEBRUARY 2017 Cabinet of Ministers approves compensation Compensation payments proposed by the Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement 28 payments to those affected and Hindu Religious Affairs, as per the Commission appointed to investigate into the incidents, February by Incidents in Welikada approved by Cabinet. Compensation payments approved for 16 prisoners who passed away (Rs. Prison on 9 November 2012 2,000,000.00 each); and 20 injured (Rs. 500,000.00 each) Examination of Sri Lanka’s Sri Lanka’s 8th Periodic Report under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of 22 Report to CEDAW Discrimination Against Women examined by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination February Against Women (CEDAW) Legislation to give effect to The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Bill 09 the International Convention was published in the Government Gazette February for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced English: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_E.pdf Disappearance Sinhala: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_S.pdf Tamil: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_T.pdf -

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

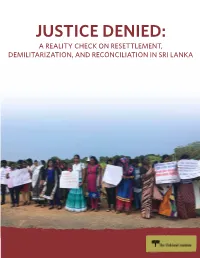

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Hansard (213-16)

213 වන කාණ්ඩය - 16 වන කලාපය 2012 ෙදසැම්බර් 08 වන ෙසනසුරාදා ெதாகுதி 213 - இல. 16 2012 சம்பர் 08, சனிக்கிழைம Volume 213 - No. 16 Saturday, 08th December, 2012 පාලෙනත වාද (හැනසා) பாராமன்ற விவாதங்கள் (ஹன்சாட்) PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES (HANSARD) ල වාතාව அதிகார அறிக்ைக OFFICIAL REPORT (අෙශෝධිත පිටපත /பிைழ தித்தப்படாத /Uncorrected) අන්තර්ගත පධාන කරුණු නිෙව්දන : විෙශෂේ ෙවෙළඳ භාණ්ඩ බදු පනත : ෙපොදු රාජ මණ්ඩලීය පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමය, අන්තර් නියමය පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමය සහ “සාක්” පාර්ලිෙම්න්තු සංගමෙය් ඒකාබද්ධ වාර්ෂික මහා සභා රැස්වීම නිෂපාදන් බදු (විෙශෂේ විධිවිධාන) පනත : ශී ලංකා පජාතාන්තික සමාජවාදී ජනරජෙය් නිෙයෝගය ෙශෂේ ඨාධිකරණෙය්් අග විනිශචයකාර් ධුරෙයන් ගරු (ආචාර්ය) ශිරානි ඒ. බණ්ඩාරනායක මහත්මිය ඉවත් කිරීම සුරාබදු ආඥාපනත : සඳහා අතිගරු ජනාධිපතිවරයා ෙවත පාර්ලිෙම්න්තුෙව් නියමය ෙයෝජනා සම්මතයක් ඉදිරිපත් කිරීම පිණිස ආණ්ඩුකම වවසථාෙව්් 107(2) වවසථාව් පකාර ෙයෝජනාව පිළිබඳ විෙශෂේ කාරක සභාෙව් වාර්තාව ෙර්ගු ආඥාපනත : ෙයෝජනාව පශනවලට් වාචික පිළිතුරු වරාය හා ගුවන් ෙතොටුෙපොළ සංවර්ධන බදු පනත : ශී ලංකාෙව් පථම චන්දිකාව ගුවන්ගත කිරීම: නිෙයෝගය විදුලි සංෙද්ශ හා ෙතොරතුරු තාක්ෂණ අමාතතුමාෙග් පකාශය ශී ලංකා අපනයන සංවර්ධන පනත : විසර්ජන පනත් ෙකටුම්පත, 2013 - [විසිතුන්වන ෙවන් කළ නිෙයෝගය දිනය]: [ශීර්ෂ 102, 237-252, 280, 296, 323, 324 (මුදල් හා කමසම්පාදන);] - කාරක සභාෙව්දී සලකා බලන ලදී. -

Monthly Report of the Consultative Committees (November – 2014)

අංක இல 7 (2) No. හවැ පා ෙ ෙ පළවැ සැවාරය උපෙශක කාරක සභා මාක වා තාව (2014 --- ෙන$වැ බ ෙන$වැ බ )))) ஏழாவP பாராfமyறwதிy YதலாவP Buடwெதாட} ஆேலாசைனp Ahpகளிy மாதாxத அறிpைக ((( நவ{ப} மாத{ ––– 2014 ))) First Session of the Seventh Parliament Monthly Report of the Consultative Committees (November – 2014) උපෙශක කාරක සභා මාක වා තාව (2014 ෙන$වැ බ ) අ)මැ*ය ලැ,ම මත මාක වා තාවට ඇළ කරන ලද කාරක සභා කා ය සටහ පහත දැ0ෙ . උපෙශක කාරක සභාෙ නම 1නය 1 ෙ2ය ෛවද4 2014.08.20 2 ජල ස පාදන හා ජලාපවාහන (8ෙශ9ෂ සභාව) 2014.09.23 3 = ක මා ත සංව ධන 2014.09.23 4 ?න@ථාපන හා බ ධනාගාර C*සංස්කරණ 2014.10.09 5 ක ක@ හා ක ක@ සබඳතා 2014.10.10 6 වනGH ස ප සංර0ෂණ 2014.10.10 7 8ෙශ9ෂ ව4ාපෘ* 2014.10.10 8 තා0ෂණ හා ප ෙJෂණ 2014.10.10 9 දK හා Lම ස පාදන 2014.10.21 10 Mවර හා ජලජ ස ප සංව ධන 2014.10.23 11 ජල ස පාදන හා ජලාපවාහන 2014.10.27 12 සංස්කෘ*ක හා කලා 2014.10.28 13 පළා පාලන හා පළා සභා 2014.11.05 14 පPසර හා ?න ජනQය බලශ0* 2014.11.05 15 RS අපනයන ෙභTග Cව ධන 2014.11.05 16 Uඩා 2014.11.05 17 8ෙශ WXයා Cව ධන හා Rභසාධන 2014.11.10 18 ෙසYඛ4 2014.11.13 19 ජා*ක භාෂා හා සමාජ ඒකාබධතා 2014.11.18 20 ස Cදා\ක ක මා ත හා ]ඩා ව4වසාය සංව ධන 2014.11.19 21 ක මා ත හා වා^ජ 2014.11.20 22 ප_ ස ප හා `ාaය Cජා සංව ධන 2014.11.21 23 අධ4ාපන 2014.11.21 (2) උපෙශක කාරක සභා මාක වා තාව (2014 ෙන$වැ බ ) ෙ2ය ෛවද4 කටb cdබඳ උපෙශක කාරක සභාෙ දහසයවැ Wස්Hම --- 2014 අෙගTස් 202020 පැeණ f කාරක සgක ම h ග@ සා ද 1සානායක මහතා (සභාප*) ග@ මi ද අමරHර මහතා ග@ අෙශT0 අෙjංහ මහතා පැeණ f කාරක සgක ෙන$වන ම h ග@ Rස ත ?ංkලෙ මහතා ග@ එ .එK.ඒ.එ . -

In the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for a mandate in the nature of Writ of Certiorari and Prohibition in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution CA (Writ) Application No: 148 /2012 J. M. Lakshman Jayasekara Director General, National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor, Sethsiti paya, Battaramulla. PETITIONER 1. S.M.Gotabaya Jayarathne, Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla. 1st RESPONDENT 1.A P.H.L. Wimalasiri Perera Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla Present Secretary ADDED 1A RESPONDENT 2. Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Chairman, 3. Palitha Kumarasinghe P.C, Member, 4. Mrs. Sirimavo A. Wijayaratne, Member, 5. Ananda Seneviratne, Member 6. N.H. Pathirana, Member, 7. S. Thillanadarajah, Member, 8. M.B.W. Ariyawansa, Member, 9. M.A.Mohomed Nahiya, Member, 10. P.M.L.C. Seneviratne Secretary, All of Public Services Commission, 177, Nawala Road, Colombo 5. 11. Attorney General Attorney General's department, Colombo 12. 12. Hon. Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne Ministry of Buddha Sasana & Religious Affairs 13. Hon. Ratnasiri Wickramanayake Ministry of Good Governance & Infrastructure Facilities 14. Hon. D. E. W. Gunasekera Ministry of Human Resources 15. Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Ministry of Rural Affairs 16. Hon. P. Dayaratne Ministry of Food Security 17. Hon. A. H. M. Fowzie Ministry of Urban Affairs 18. Hon. S. B. Navinne Ministry of Consumer Welfare 19. Hon. Piyasena Gamage Ministry of National Resources 20. Hon. (Prof) Tissa Vitharana Ministry of Scientific Affairs 21. -

REFUGEECOSATT3.Pdf

+ + + Refugees and IDPs in South Asia Editor Dr. Nishchal N. Pandey + + Published by Consortium of South Asian Think Tanks (COSATT) www.cosatt.org Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) www.kas.de First Published, November 2016 All rights reserved Printed at: Modern Printing Press Kathmandu, Nepal. Tel: 4253195, 4246452 Email: [email protected] + + Preface Consortium of South Asian Think-tanks (COSATT) brings to you another publication on a critical theme of the contemporary world with special focus on South Asia. Both the issues of refugees and migration has hit the headlines the world-over this past year and it is likely that nation states in the foreseeable future will keep facing the impact of mass movement of people fleeing persecution or war across international borders. COSATT is a network of some of the prominent think-tanks of South Asia and each year we select topics that are of special significance for the countries of the region. In the previous years, we have delved in detail on themes such as terrorism, connectivity, deeper integration and the environment. In the year 2016, it was agreed by all COSATT member institutions that the issue of refugees and migration highlighting the interlinkages between individual and societal aspirations, reasons and background of the cause of migration and refugee generation and the role of state and non-state agencies involved would be studied and analyzed in depth. It hardly needs any elaboration that South Asia has been both the refugee generating and refugee hosting region for a long time. South Asian migrants have formed some of the most advanced and prosperous diasporas in the West. -

Sri Lanka: Tamil Politics and the Quest for a Political Solution

SRI LANKA: TAMIL POLITICS AND THE QUEST FOR A POLITICAL SOLUTION Asia Report N°239 – 20 November 2012 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS ................................................. i I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................. 1 II. TAMIL GRIEVANCES AND THE FAILURE OF POLITICAL RESPONSES ........ 2 A. CONTINUING GRIEVANCES ........................................................................................................... 2 B. NATION, HOMELAND, SEPARATISM ............................................................................................. 3 C. THE THIRTEENTH AMENDMENT AND AFTER ................................................................................ 4 D. LOWERING THE BAR .................................................................................................................... 5 III. POST-WAR TAMIL POLITICS UNDER TNA LEADERSHIP ................................. 6 A. RESURRECTING THE DEMOCRATIC TRADITION IN TAMIL POLITICS .............................................. 6 1. The TNA ..................................................................................................................................... 6 2. Pro-government Tamil parties ..................................................................................................... 8 B. TNA’S MODERATE APPROACH: YET TO BEAR FRUIT .................................................................. 8 1. Patience and compromise in negotiations -

Report of the Secretary-General's Panel Of

REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL’S PANEL OF EXPERTS ON ACCOUNTABILITY IN SRI LANKA 31 March 2011 REPORT OF THE SECRETARY-GENERAL’S PANEL OF EXPERTS ON ACCOUNTABILITY IN SRI LANKA Executive Summary On 22 June 2010, the Secretary-General announced the appointment of a Panel of Experts to advise him on the implementation of the joint commitment included in the statement issued by the President of Sri Lanka and the Secretary-General at the conclusion of the Secretary-General’s visit to Sri Lanka on 23 March 2009. In the Joint Statement, the Secretary-General “underlined the importance of an accountability process”, and the Government of Sri Lanka agreed that it “will take measures to address those grievances”. The Panel’s mandate is to advise the Secretary- General regarding the modalities, applicable international standards and comparative experience relevant to an accountability process, having regard to the nature and scope of alleged violations of international humanitarian and human rights law during the final stages of the armed conflict in Sri Lanka. The Secretary-General appointed as members of the Panel Marzuki Darusman (Indonesia), Chair; Steven Ratner (United States); and Yasmin Sooka (South Africa). The Panel formally commenced its work on 16 September 2010 and was assisted throughout by a secretariat. Framework for the Panel’s work In order to understand the accountability obligations arising from the last stages of the war, the Panel undertook an assessment of the “nature and scope of alleged violations” as required by its Terms of Reference. The Panel’s mandate however does not extend to fact- finding or investigation. -

Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability

International Human Rights Law Journal Volume 1 Issue 1 DePaul International Human Rights Law Article 2 Journal: The Inaugural Issue 2015 Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability Mytili Bala Robert L. Bernstein International Human Rights Fellow at the Center for Justice and Accountability, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/ihrlj Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, Human Geography Commons, Human Rights Law Commons, International Relations Commons, Law and Politics Commons, Military, War, and Peace Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Bala, Mytili (2015) "Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability," International Human Rights Law Journal: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 2. Available at: https://via.library.depaul.edu/ihrlj/vol1/iss1/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the College of Law at Via Sapientiae. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Human Rights Law Journal by an authorized editor of Via Sapientiae. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Transitional Justice in Sri Lanka: Rethinking Post-War Diaspora Advocacy for Accountability Cover Page Footnote Mytili Bala is the Robert L. Bernstein International Human Rights Fellow at the Center for Justice and Accountability. Mytili received her B.A. from the University of Chicago, and her J.D. from Yale Law School. The author thanks the Bernstein program at Yale Law School, the Center for Justice and Accountability, and brave colleagues working for accountability and post-conflict transformation in Sri Lanka. -

Addendum No. 14(4)

( ) [ Seventh Parliament -First Session] No. 14 (4).] ADDENDUM TO THE ORDER BOOK No. 14 OF PARLIAMENT Issued on Wednesday, June 10, 2015 Tuesday, June 23, 2015 NOTICE OF MOTIONS AND ORDERS OF THE DAY * Registration of Persons (Amendment) Bill — Second Reading. * The Minister of Ports and Shipping,— Regulations under the Licensing of Shipping Agents Act,— That the Regulations made by the Minister of Highways, Ports and Shipping under Section 10 read with Section 3 of the Licensing of Shipping Agents Act, No. 10 of 1972 and published in the Gazette Extraordinary No. 1877/26 of 28th August 2014, which were presented on 09.06.2015, be approved. (Cabinet approval signified.) * The Minister of Labour,— Regulations under the Wages Boards Ordinance,— That the Regulations made by the Minister of Labour under Section 63 of the Wages Board Ordinance (Chapter 136), which were presented on 09.06.2015, be approved. (Cabinet approval signified.) * The Minister of Tourism and Sports,— Regulations under the Convention against Doping in Sports Act,— That the Regulations made by the Minister of Tourism and Sports under Section 34 read with Section 3 of the Convention against Doping in Sports Act, No. 33 of 2013 and published in the Gazette Extraordinary No. 1913/7 of 05th May 2015, which were presented on 06.09.2015, be approved. * Indicates Government Business (2) NOTICE OF MOTIONS FOR WHICH NO DATES HAVE BEEN FIXED P. 310/’15 Hon. D.M. Jayaratne Hon. Dinesh Gunawardena Hon. Vasudeva Nanayakkara Hon. Gamini Lokuge Hon. Dullas Alahapperuma Hon. Kumara Welgama Hon. (Ms.) Kamala Ranathunga Hon. Gitanjana Gunawardena Hon. -

Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate Jyotsna Shankar Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate Jyotsna Shankar Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Shankar, Jyotsna, "Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 201. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/201 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE POST-CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION IN SRI LANKA AND CYPRUS: AVOIDING A STALEMATE SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR BILL ASCHER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY JYOTSNA SHANKAR FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL-SPRING/2010-2011 APRIL 12, 2011 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS .............................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER ONE: GOALS ......................................................................................... 4 SRI LANKA ................................................................................................................. 4 CYPRUS .................................................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND AND TRENDS ................................................... 19 -

April - June 2016

Issue No. 151 April - June 2016 A protest on a Human Rights issue “In the last thirty or more years we have seen the failure of those holding high political office to observe and respect the spirit of the Constitution and the law. One can see many people blaming the 1978 Consti- tution for the many ills in our country, but the fault lies not in the Constitution, but in the men and women who have failed to operate the Constitution in the correct spirit” by Saliya Pieris - The Sunday Leader - 01/05/2016 Human Rights Review : April - June Institute of Human Rights 2 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Editorial 03 Signs of discontent Buddha on excessive taxes, and good governance 05 Possibility Of All MPs Getting Ministerial Posts – Dr. Nirmal Ranjith Devasiri If we don’t kill corruption, it will kill Sri Lanka 06 Like Oliver Twist, Our Political Fat-Cats Want More 07 The Menace of a clannish herd Sajin Vass: Witness Most Corrupt 08 Of Taxation, Inland Revenue And Panama Papers Yahapalanaya is not transparent - Prof.Sarath Wijesooriya 09 Citizen Power And The Opposition 11 More than mere obstacles on the road to Governance? Justice Delayed Is Corruption Condoned 13 Continuing To Protect Thieves? 14 Situation in the North & East Seven years after the end of Sri Lanka’s War 14 Media Attacks Journalist attacked within MC premises 15 UNHRC & The International Front Torture still continues: UN rapporteurs slam CID, TID 15 Armitage Does Mediator Role; Meets TNA To Discuss Issues 16 Alleged war crimes: PM announces probe will be domestic, no foreign