Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate Jyotsna Shankar Claremont Mckenna College

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As at 28 February 2017

as at 01 M a rch 2017 FESTINA LENTE ADVANCING HUMAN RIGHTS, ACCOUNTABILITY, RECONCILIATION AND GOOD GOVERNANCE IN SRI LANKA January 2015 – March 2017 1 STEP OBSERVATIONS DATE MARCH 2017 Land release The Air Force released 42 acres of private land to the Mullaitivu GA, ending the protests staged by 01 people in front of the Air Force Base since January 2017. March FEBRUARY 2017 Cabinet of Ministers approves compensation Compensation payments proposed by the Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement 28 payments to those affected and Hindu Religious Affairs, as per the Commission appointed to investigate into the incidents, February by Incidents in Welikada approved by Cabinet. Compensation payments approved for 16 prisoners who passed away (Rs. Prison on 9 November 2012 2,000,000.00 each); and 20 injured (Rs. 500,000.00 each) Examination of Sri Lanka’s Sri Lanka’s 8th Periodic Report under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of 22 Report to CEDAW Discrimination Against Women examined by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination February Against Women (CEDAW) Legislation to give effect to The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Bill 09 the International Convention was published in the Government Gazette February for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced English: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_E.pdf Disappearance Sinhala: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_S.pdf Tamil: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_T.pdf -

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

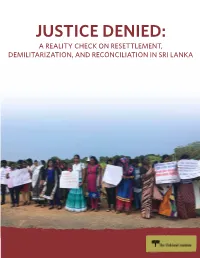

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking?

CYPRUS CENTRE 2/2007 REPORT 2/2007 Is the Turkish Cypriot Population Shrinking? Shrinking? Cypriot Population Turkish Is the The demography of north Cyprus is one of the most contested issues related to the island’s division. In particular, the number of indigenous Turkish Cypriots and Turkish immigrants living in the north has long been a source of dispute, not only among the island’s diplomats and politicians but also among researchers and activists. Until recently, the political use of demog- raphy has hindered comprehensive study of the ethno-demographic make-up of the north, while at the same time making a thorough demographic study all the more imperative. The present report addresses this situation by providing an analysis of the results of the 2006 census of north Cyprus, comparing these fi gures with the results of the previous census. The report focuses mainly on identifying the percentage of the population of north Cyprus who are of Turkish-mainland origin and also possess Turkish Cypriot citizenship – an important factor given claims that such citizens play an signifi cant role in elections in the north. In addi- tion, the report examines the arrival dates of Turkish nationals in order to analyze patterns of migration. This, in turn, is indicative of the numbers of naturalized Turkish Cypriot citizens who have arrived in Cyprus as part of an offi cial policy. The report also presents estimates for Turkish Cypriot emigration to third countries, based on immigration and census fi gures from the two main host countries: the United Kingdom and Australia. Following analysis of these latter fi gures and the results of the 2006 census, it is argued that claims of massive emigration by Turkish Cypriots to third countries are largely misleading. -

Download the Article In

FREESIDE EUROPE ONLINE ACADEMIC JOURNAL 2020/1 ALUMNI ISSUE www.freesideeurope.com DOI 10.51313/alumni-2020-9 Categories and social meanings: An analysis of international students’ language practices in an international school Jani-Demetriou Bernadett ELTE Doctoral School of Linguistics [email protected] Abstract Bilingual educational programmes in recent years received criticism from translanguaging or superdiversity scholars. These programmes follow either the subtractive or the additive models of bilingual education (García 2009), in both of which the languages are considered as separate systems. This distinction is considered as “inadequate to describe linguistic diversity” (García 2009: 142) and masks the real diversity of difference by focusing only on languages. Thinking in terms of plurilingualism and multiculturalism “might contribute to a continuation of thinking in terms of us-versus-them, essentializing cultural or ethnic differences” (Geldof 2018: 45). The present study argues that a critical ethnographic sociolinguistic approach provides a more relevant analysis of children’s language practices. From this critical perspective, speaking is highlighted instead of languages and considered as action in which the linguistic resources carry social meaning (Blommaert–Rampton 2011). This paper introduces the findings of an ethnographic fieldwork set in an international summer school where linguistic and ethnic diversity is a commonplace, although a strict English-only language policy applies in order to achieve the school’s pedagogical goals. The aim of the research has been to find out how students from various cultural background are dealing with ethnical and linguistic diversity and to analyse how the processes of normalisation (Geldof 2018) among students and teachers create values and categories accepted as norms by the group. -

The New Energy Triangle of Cyprus-Greece-Israel: Casting a Net for Turkey?

THE NEW ENERGY TRIANGLE OF CYPRUS-GREECE-ISRAEL: CASTING A NET FOR TURKEY? A long-running speculation over massive natural gas reserves in the tumultuous area of the Southeastern Mediterranean became a reality in December 2011 and the discovery's timing along with other grave and interwoven events in the region came to create a veritable tinderbox. The classic “Rubik's cube” puzzle here is in perfect sync with the realities on the ground and how this “New Energy Triangle” (NET) of newfound and traditional allies' actions (Cyprus, Greece and Israel) towards Turkey will shape and inevitably affect the new balance of power in this crucial part of the world. George Stavris* *George Stavris is a visiting researcher at Dundee University's Centre for Energy, Petroleum and Mineral Law and Policy working on the geostrategic repercussions in the region of the “New Energy Alliance” (NET) of Cyprus, Greece and Israel. 87 VOLUME 11 NUMBER 2 GEORGE STAVRIS long-running speculation over massive natural gas reserves in the tumultuous area of the Southeastern Mediterranean and in Cyprus’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) became a reality in A December 2011 when official reports of the research and scoping were released. Nearby, Israel has already confirmed its own reserves right next to Cyprus’ EEZ. However the location of Cypriot reserves with all the intricacies of the intractable “Cyprus Problem” and the discovery’s timing along with other grave and interwoven events in the region came to create a veritable tinderbox. A rare combination of the above factors and ensuing complications have created not just a storm in the area but almost, indisputably, the rare occasion of a “Perfect Storm” in international politics with turbulence reaching far beyond the shores of the Mediterranean “Lake”. -

Malta & Cyprus

13 DAY CULTURAL TOUR MALTA & CYPRUS $ PER PERSON 3199 TWIN SHARE TYPICALLY $5399 KYRENIA • VALLETTA • BIRGU • KARPAZ PENINSULA THE OFFER 13 DAY MALTA & CYPRUS Ancient temples steeped in myth and legend, azure seas and sun-kissed beaches, colourful cities with hidden laneways and marketplaces to explore… there’s a $3199 reason Malta and Cyprus are tipped as two of the Mediterranean’s rising stars. Experience them both on this incredible 13 day cultural tour. Discover into the rich history and architecture of UNESCO World Heritage listed Valletta; enjoy a guided tour of beautiful Birgu, one of Malta’s ancient fortified ‘Three Cities’; take a jeep safari through the colourful cities and villages of Malta’s sister island Gozo, which is long associated with Homer’s Odyssey; and enjoy two days at leisure to soak up the relaxed island lifestyle of Malta. Stay in the ancient city of Kyrenia in Cyprus, known for its horseshoe-shaped harbour and cobblestone laneways; travel to St. Hilarion Castle high located in the Kyrenian Mountains; journey along the isolated yet beautiful Karpaz Peninsula, known for its wild donkeys; visit the famous Apostolos Andreas Monastery; relax with two days at leisure in Cyprus and more! With return international flights, an additional flight between Malta and Cyprus, 10 nights waterfront accommodation, return airport transfers and more, this island getaway will surprise you in ways you didn’t know possible. *Please note: all information provided in this brochure is subject to both change and availability. Prior to purchase please check the current live deal at tripadeal.com.au or contact our customer service team on 135 777 for the most up-to-date information. -

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict?

Ancient Cyprus: Island of Conflict? Maria Natasha Ioannou Thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy Discipline of Classics School of Humanities The University of Adelaide December 2012 Table of Contents Abstract ................................................................................................................ III Declaration........................................................................................................... IV Acknowledgements ............................................................................................. V Introduction ........................................................................................................... 1 1. Overview .......................................................................................................... 1 2. Background and Context ................................................................................. 1 3. Thesis Aims ..................................................................................................... 3 4. Thesis Summary .............................................................................................. 4 5. Literature Review ............................................................................................. 6 Chapter 1: Cyprus Considered .......................................................................... 14 1.1 Cyprus’ Internal Dynamics ........................................................................... 15 1.2 Cyprus, Phoenicia and Egypt ..................................................................... -

Efficiency and Productivity in Sri Lanka's Banking Sector

University of Wollongong Research Online University of Wollongong Thesis Collection 1954-2016 University of Wollongong Thesis Collections 2016 Efficiency and oductivitypr in Sri Lanka’s banking sector: Evidence from the post-conflict era Bolanda Hewa Thilakaweera University of Wollongong Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.uow.edu.au/theses University of Wollongong Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorise you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: This work is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part of this work may be reproduced by any process, nor may any other exclusive right be exercised, without the permission of the author. Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. A court may impose penalties and award damages in relation to offences and infringements relating to copyright material. Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. Unless otherwise indicated, the views expressed in this thesis are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of the University of Wollongong. Recommended Citation Thilakaweera, Bolanda Hewa, Efficiency and oductivitypr in Sri Lanka’s banking sector: Evidence from the post-conflict era, Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Accounting, Economics and Finance, University of Wollongong, 2016. -

In the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for a mandate in the nature of Writ of Certiorari and Prohibition in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution CA (Writ) Application No: 148 /2012 J. M. Lakshman Jayasekara Director General, National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor, Sethsiti paya, Battaramulla. PETITIONER 1. S.M.Gotabaya Jayarathne, Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla. 1st RESPONDENT 1.A P.H.L. Wimalasiri Perera Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla Present Secretary ADDED 1A RESPONDENT 2. Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Chairman, 3. Palitha Kumarasinghe P.C, Member, 4. Mrs. Sirimavo A. Wijayaratne, Member, 5. Ananda Seneviratne, Member 6. N.H. Pathirana, Member, 7. S. Thillanadarajah, Member, 8. M.B.W. Ariyawansa, Member, 9. M.A.Mohomed Nahiya, Member, 10. P.M.L.C. Seneviratne Secretary, All of Public Services Commission, 177, Nawala Road, Colombo 5. 11. Attorney General Attorney General's department, Colombo 12. 12. Hon. Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne Ministry of Buddha Sasana & Religious Affairs 13. Hon. Ratnasiri Wickramanayake Ministry of Good Governance & Infrastructure Facilities 14. Hon. D. E. W. Gunasekera Ministry of Human Resources 15. Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Ministry of Rural Affairs 16. Hon. P. Dayaratne Ministry of Food Security 17. Hon. A. H. M. Fowzie Ministry of Urban Affairs 18. Hon. S. B. Navinne Ministry of Consumer Welfare 19. Hon. Piyasena Gamage Ministry of National Resources 20. Hon. (Prof) Tissa Vitharana Ministry of Scientific Affairs 21. -

The UPU CEO Forum Is Form for Future Cooperation

Moving the postal sector forward since 1875 July 2018 | Nº4/17 Speakers' Formidable 10 Corner force: CEOs look Cover 14 story toward alliance Envisioning 21 a postal building future 3 to 7 September 2018 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia UPU is holding its second-ever Extraordinary Congress, calling together some 1,000 delegates from its 192 member countries in Addis Ababa this September. They will take crucial decisions regarding the future of the UPU and the postal sector, including: • Implementation of the UPU's Integrated Product Plan and the Integrated Remuneration Plan • Reform of the UPU • Reform of the system applied to contributions by UPU member countries • Sustainability of the UPU Provident Scheme Government ministers and other senior decision-makers from around the globe will also participate in a special Ministerial Strategy Conference September 6 & 7. They will discuss how the postal sector can better serve nations and citizens and review the implementation of the UPU World Postal Strategy adopted at the Istanbul Congress in 2016. Registration is now open. Please visit the UPU website for more details on the event and information for participants. Follow along on social media: #postaldialogue www.upu.int CONTENTS COVER STORY 14 UNION POSTALE is the Universal Postal Union’s flagship magazine, Formidable force: founded in 1875. It is published quarterly in seven languages and takes a closer look at UPU activities, featuring international news and developments CEOs look toward from the postal sector. The magazine regularly publishes well researched articles on topical issues alliance building facing the industry, as well as interviews with the sector’s leading individuals. -

Cyprus & Malta in International Tax Structures

Focus Business Services International Group Focus Business Services (Int’l) Ltd Focus Business Services (Cyprus) Ltd Focus Business Services (Malta) Ltd A K Kotsomitis Chartered Aris Kotsomitis Accountants Limited BSc FCA CPA TEP MoID Chairman *Regulated EU Professionals* Head of International Tax Planning www.fbscyprus.com [email protected] / +357 22 456 363 Cyprus corporate structures in international tax planning www.fbscyprus.com [email protected] / +357 22 456 363 Structure of the Presentation 1. Brief Introduction to the FBS Int’l Group 2. Overview of the Cyprus Tax System 3. Specific Features of the Cyprus Tax System 4. Tax Planning Ideas – Structures (Critical Structuring Issues To Bear in Mind – Fees/Costs/Budget …found in appendix) www.fbscyprus.com [email protected] / +357 22 456 363 Introducing the FBS International Group www.fbscyprus.com [email protected] / +357 22 456 363 Leading Professional Services Group Cyprus (HO) – Malta Established 1998 we are now a leading professional services and corporate services provider, located mainly in Cyprus (Head Office) and Malta (2nd biggest office) We provide the entire range of services needed under one roof. From formation ... to liquidation! Independent, full-scope multi-disciplinary professional group (our in-house partners are lawyers, accountants, auditors, tax practitioners / advisors, wealth managers) www.fbscyprus.com [email protected] / +357 22 456 363 Recognized locally and Internationally Fox TV Network in the US (Fox 5 News – 25 million business viewers!) is producing a special program on Cyprus as an international financial centre – currently under filming… Our Chairman (Aris Kotsomitis) was selected to represent the Cyprus professional sector in the program along with the President, the Finance Minister and the Minister of Commerce of The Republic of Cyprus www.fbscyprus.com [email protected] / +357 22 456 363 Focus Business Services (est. -

REFUGEECOSATT3.Pdf

+ + + Refugees and IDPs in South Asia Editor Dr. Nishchal N. Pandey + + Published by Consortium of South Asian Think Tanks (COSATT) www.cosatt.org Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) www.kas.de First Published, November 2016 All rights reserved Printed at: Modern Printing Press Kathmandu, Nepal. Tel: 4253195, 4246452 Email: [email protected] + + Preface Consortium of South Asian Think-tanks (COSATT) brings to you another publication on a critical theme of the contemporary world with special focus on South Asia. Both the issues of refugees and migration has hit the headlines the world-over this past year and it is likely that nation states in the foreseeable future will keep facing the impact of mass movement of people fleeing persecution or war across international borders. COSATT is a network of some of the prominent think-tanks of South Asia and each year we select topics that are of special significance for the countries of the region. In the previous years, we have delved in detail on themes such as terrorism, connectivity, deeper integration and the environment. In the year 2016, it was agreed by all COSATT member institutions that the issue of refugees and migration highlighting the interlinkages between individual and societal aspirations, reasons and background of the cause of migration and refugee generation and the role of state and non-state agencies involved would be studied and analyzed in depth. It hardly needs any elaboration that South Asia has been both the refugee generating and refugee hosting region for a long time. South Asian migrants have formed some of the most advanced and prosperous diasporas in the West.