DFAT COUNTRY INFORMATION REPORT SRI LANKA 24 January 2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London Phd In

Northern Sri Lanka Jane Derges University College London PhD in Social Anthropology UMI Number: U591568 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U591568 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 Fig. 1. Aathumkkaavadi DECLARATION I, Jane Derges, confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources I confirm that this has been indicated the thesis. ABSTRACT Following twenty-five years of civil war between the Sri Lankan government troops and the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), a ceasefire was called in February 2002. This truce is now on the point of collapse, due to a break down in talks over the post-war administration of the northern and eastern provinces. These instabilities have lead to conflicts within the insurgent ranks as well as political and religious factions in the south. This thesis centres on how the anguish of war and its unresolved aftermath is being communicated among Tamils living in the northern reaches of Sri Lanka. -

As at 28 February 2017

as at 01 M a rch 2017 FESTINA LENTE ADVANCING HUMAN RIGHTS, ACCOUNTABILITY, RECONCILIATION AND GOOD GOVERNANCE IN SRI LANKA January 2015 – March 2017 1 STEP OBSERVATIONS DATE MARCH 2017 Land release The Air Force released 42 acres of private land to the Mullaitivu GA, ending the protests staged by 01 people in front of the Air Force Base since January 2017. March FEBRUARY 2017 Cabinet of Ministers approves compensation Compensation payments proposed by the Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement 28 payments to those affected and Hindu Religious Affairs, as per the Commission appointed to investigate into the incidents, February by Incidents in Welikada approved by Cabinet. Compensation payments approved for 16 prisoners who passed away (Rs. Prison on 9 November 2012 2,000,000.00 each); and 20 injured (Rs. 500,000.00 each) Examination of Sri Lanka’s Sri Lanka’s 8th Periodic Report under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of 22 Report to CEDAW Discrimination Against Women examined by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination February Against Women (CEDAW) Legislation to give effect to The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Bill 09 the International Convention was published in the Government Gazette February for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced English: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_E.pdf Disappearance Sinhala: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_S.pdf Tamil: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_T.pdf -

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

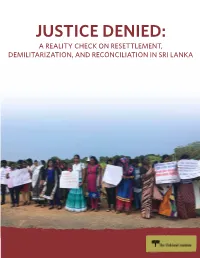

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

The Case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Journal of Social Sciences 2017 40 (1): 41-52 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.4038/sljss.v40i1.7500 RESEARCH ARTICLE Collective ritual as a way of transcending ethno-religious divide: the case of Kataragama Pāda Yātrā in Sri Lanka# Anton Piyarathne* Department of Social Studies, Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences, The Open University of Sri Lanka, Nawala, Sri Lanka. Abstract: Sri Lanka has been in the prime focus of national and who are Sinhala speakers, are predominantly Buddhist, international discussions due to the internal war between the whereas the ethnic Tamils, who communicate in the Tamil Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) and the Sri Lankan language, are primarily Hindu. These two ethnic groups government forces. The war has been an outcome of the are often recognised as rivals involved in an “ethnic competing ethno-religious-nationalisms that raised their heads; conflict” that culminated in war between the LTTE (the specially in post-colonial Sri Lanka. Though today’s Sinhala Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam, a military movement and Tamil ethno-religious-nationalisms appear as eternal and genealogical divisions, they are more of constructions; that has battled for the liberation of Sri Lankan Tamils) colonial inventions and post-colonial politics. However, in this and the government. Sri Lanka suffered heavily as a context it is hard to imagine that conflicting ethno-religious result of a three-decade old internal war, which officially groups in Sri Lanka actually unite in everyday interactions. ended with the elimination of the leadership of the LTTE This article, explains why and how this happens in a context in May, 2009. -

Assessing the Role of Human Rights Protections for Sexual Minorities in HIV Prevention in Asia

Assessing the Role of Human Rights Protections for Sexual Minorities in HIV Prevention in Asia: A Meta-Analysis by JAMES EDWARD ANDERSON, B.P.A.P.M. A thesis submitted to The Faculty of Graduate Studies and Research in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The Norman Paterson School of International Affairs Carleton University Ottawa, Ontario March 1,2012 © 2012, James Edward Anderson Library and Archives Bibliotheque et Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91560-8 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-91560-8 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distrbute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Sri Lanka's Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire

Sri Lanka’s Potemkin Peace: Democracy Under Fire Asia Report N°253 | 13 November 2013 International Crisis Group Headquarters Avenue Louise 149 1050 Brussels, Belgium Tel: +32 2 502 90 38 Fax: +32 2 502 50 38 [email protected] Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i Recommendations..................................................................................................................... iii I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Northern Province Elections and the Future of Devolution ............................................ 2 A. Implementing the Thirteenth Amendment? ............................................................. 3 B. Northern Militarisation and Pre-Election Violations ................................................ 4 C. The Challenges of Victory .......................................................................................... 6 1. Internal TNA discontent ...................................................................................... 6 2. Sinhalese fears and charges of separatism ........................................................... 8 3. The TNA’s Tamil nationalist critics ...................................................................... 9 D. The Legal and Constitutional Battleground .............................................................. 12 E. A Short- -

Sri Lanka Anketell Final

The Silence of Sri Lanka’s Tamil Leaders on Accountability for War Crimes: Self- Preservation or Indifference? Niran Anketell 11 May 2011 A ‘wikileaked’ cable of 15 January 2010 penned by Patricia Butenis, U.S Ambassador to Sri Lanka, entitled ‘SRI LANKA WAR-CRIMES ACCOUNTABILITY: THE TAMIL PERSPECTIVE’, suggested that Tamils within Sri Lanka are more concerned about economic and social issues and political reform than about pursuing accountability for war crimes. She also said that there was an ‘obvious split’ between diaspora Tamils and Tamils within Sri Lanka on how and when to address the issue of accountability. Tamil political leaders for their part, notably those from the Tamil National Alliance (TNA), had made no public remarks on the issue of accountability until 18 April 2011, when they welcomed the UN Secretary-General’s Expert Panel report on accountability in Sri Lanka. That silence was observed by some as an indication that Tamils in Sri Lanka have not prioritised the pursuit of accountability to the degree that their diaspora counterparts have. At a panel discussion on Sri Lanka held on 10 February 2011 in Washington D.C., former Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia, Donald Camp, cited the Butenis cable to argue that the United States should shift its focus from one of pursuing accountability for war abuses to ‘constructive engagement’ with the Rajapakse regime. Camp is not alone. There is significant support within the centres of power in the West that a policy of engagement with Colombo is a better option than threatening it with war crimes investigations and prosecutions. -

April - June 2015

Issue No. 147 April - June 2015 National Anthem sung in Tamil The national anthem was sung in Tamil in the presence of President Maithripala Sirisena, Prime Minister Ranil Wickremesinghe and former President Chandrika Bandaranaike Kumaratunga at an event, where the lands taken over by the mili- tary to establish a High Security Zone were handed back to the legitimate owners at Valalaai, Valikamam East on 23rr March. Human Rights Review : April - June Institute of Human Rights 2 INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Editorial 03 The New government ♦ Extracts from an article by Faizer Shaheid - PTA ALWAYS DISCRIMINAED 06 ♦ Four cheers for judicial independence 07 ♦ Presidential powers and the craving to be slaves 08 ♦ 19th Amendment: Why this indecent haste? 09 ♦ Up to president to act on COPE report: DEW 10 ♦ Arjuna Mahendran's culpability proved! ♦ Sampanthan welcomes 19A 11 ♦ The politics, economics and fundamental rights of grand corruption in Sri Lanka ♦ Sobhitha Thera interviewed by Subashini Gunaratne 12 Situation in the North & East ♦ Return of the denied land 13 ♦ Now the war is over, where do they go? ♦ Northern Spring Programme... 86 villages still powerless 14 ♦ Protest in Mullaitivu against confiscated land ♦ Special Court to hear case: MS 15 ♦ Filling the vacuum Situation in the Hill Country ♦ Koslanda Tragedy turns calamity 16 Media Freedom ♦ Tamil journalists’ woes continue 16 Sri Lanka In the International scene ♦ US PRESSES GOVT....NOTIFY FAMILIES IMMEDIATELY OF LIVING POLITICAL 17 PRISONERS... ♦ TNA wants action on war crimes ♦ Excerpts -

In the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for a mandate in the nature of Writ of Certiorari and Prohibition in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution CA (Writ) Application No: 148 /2012 J. M. Lakshman Jayasekara Director General, National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor, Sethsiti paya, Battaramulla. PETITIONER 1. S.M.Gotabaya Jayarathne, Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla. 1st RESPONDENT 1.A P.H.L. Wimalasiri Perera Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla Present Secretary ADDED 1A RESPONDENT 2. Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Chairman, 3. Palitha Kumarasinghe P.C, Member, 4. Mrs. Sirimavo A. Wijayaratne, Member, 5. Ananda Seneviratne, Member 6. N.H. Pathirana, Member, 7. S. Thillanadarajah, Member, 8. M.B.W. Ariyawansa, Member, 9. M.A.Mohomed Nahiya, Member, 10. P.M.L.C. Seneviratne Secretary, All of Public Services Commission, 177, Nawala Road, Colombo 5. 11. Attorney General Attorney General's department, Colombo 12. 12. Hon. Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne Ministry of Buddha Sasana & Religious Affairs 13. Hon. Ratnasiri Wickramanayake Ministry of Good Governance & Infrastructure Facilities 14. Hon. D. E. W. Gunasekera Ministry of Human Resources 15. Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Ministry of Rural Affairs 16. Hon. P. Dayaratne Ministry of Food Security 17. Hon. A. H. M. Fowzie Ministry of Urban Affairs 18. Hon. S. B. Navinne Ministry of Consumer Welfare 19. Hon. Piyasena Gamage Ministry of National Resources 20. Hon. (Prof) Tissa Vitharana Ministry of Scientific Affairs 21. -

Indigenizing Sexuality and National Citizenship: Shyam Selvadurai's

Indigenizing Sexuality and National Citizenship: Shyam Selvadurai’s Cinnamon Gardens Heather Smyth The intersection of feminist and postcolonial critique has enabled us to understand some of the co-implications of gendering, sexuality, and postcolonial nation building. Anne McClintock, for instance, argues that nations “are historical practices through which social difference is both invented and performed” and that “nations have historically amounted to the sanctioned institutionalization of gender difference” (89; italics in original). Women’s reproduction is put to service for the nation in both concrete and symbolic ways: women reproduce ethnicity biologically (by bearing children) and symbolically (by representing core cultural values), and the injunction to women to reproduce within the norms of marriage and ethnic identification, or heterosexual endogamy, makes women also “reproducers of the boundaries of ethnic/national groups” (Yuval-Davis and Anthias 8–9; emphasis added). National identity may be routed through gender, sexuality, and class, such that “respectability” and bourgeois norms, including heterosexuality, are seen as essential to nationalism, perhaps most notably in nations seeking in- dependence from colonial power (Mosse; de Mel). Shyam Selvadurai’s historical novel Cinnamon Gardens, set in 1927–28 Ceylon, is a valuable contribution to the study of gender and sexuality in national discourses, for it explores in nuanced ways the roots of gender norms and policed sexuality in nation building. Cinnamon Gardens indigenizes Ceylonese/ Sri Lankan homosexuality not by invoking the available rich history of precolonial alternative sexualities in South Asia, but rather by tying sexuality to the novel’s other themes of nationalism, ethnic conflict, and women’s emancipation. -

SRI LANKA: Land Ownership and the Journey to Self-Determination

Land Ownership and the Journey to Self-Determination SRI LANKA Country Paper Land Watch Asia SECURING THE RIGHT TO LAND 216 Acknowledgments Vavuniya), Mahaweli Authority of Sri Lanka, Hadabima Authority of Sri Lanka, National This paper is an abridged version of an earlier scoping Aquaculture Development Authority in Sri study entitled Sri Lanka Country Report: Land Watch Asia Lanka, Urban Development Authority, Coconut Study prepared in 2010 by the Sarvodaya Shramadana Development Authority, Agricultural and Agrarian Movement through the support of the International Land Insurance Board, Coconut Cultivation Board, Coalition (ILC). It is also written as a contribution to the Janatha Estate Dvt. Board, National Livestock Land Watch Asia (LWA) campaign to ensure that access Development Board, National Water Supply and to land, agrarian reform and sustainable development for Drainage Board, Palmyra Dvt. Board, Rubber the rural poor are addressed in development. The LWA Research Board of Sri Lanka, Sri Lanka Tea Board, campaign is facilitated by the Asian NGO Coalition for Land Reform Commission, Sri Lanka State Agrarian Reform and Rural Development (ANGOC) and Plantation Cooperation, State Timber Cooperation, involves civil society organizations in Bangladesh, Geological Survey and Mines Bureau, Lankem Cambodia, India, Indonesia, Nepal, Pakistan, the Tea and Rubber Plantation Limited, Mahaweli Philippines, and Sri Lanka. Livestock Enterprise Ltd, National Institute of Education, National Institute of Plantation Mgt., The main paper was written by Prof. CM Madduma Department of Wildlife Conservation Bandara as main author, with research partners Vindya • Non-Governmental Organizations Wickramaarachchi and Siripala Gamage. The authors Plan Sri Lanka, World Vision Lanka, CARE acknowledge the support of Dr. -

New Faces in Parliament COLOMBO Sudarshani Fernandopulle Dr

8 THE SUNDAY TIMES ELECTIONS Sunday April 18, 2010 New faces in Parliament COLOMBO Sudarshani Fernandopulle Dr. Ramesh Pathirana UPFA Nimal Senarath UPFA Born in 1960 Born in 1969. S. Udayan (Silvestri Wijesinghe Doctor by profession. A medical doctor by profes- alantin alias Uthayan) Born in 1969. R. Duminda Silva Former DMO of the sion. Born in 1972. Educated at Kirindigalla MV Born 1974. Negombo Hospital. Son of former Education Studied at Delft Maha and Ibbagamuwa MV. Businessman. Served for more than 10 Minister Richard Pathirana. Vidyalaya. Profession – Businessman. Studied at St. Peter’s Col- years at the Children’s Health Studied at Richmond Col- Joined EPDP in 1992. UNP Organiser of Rambo- lege, Colombo. Care Bureau of the Health. lege, Galle. Former deputy Chairman of dagalla in 2006. Elected to the Western Pro- Chief Organiser of Akmeemana. the Karaveddy Pradeshiya Sabha. Elected to the North Western Provincial Coun- vincial Council in 2009 on the Executive Committee Member of the Cey-Nor cil in 2009. UPFA ticket and topped the preferential votes Fishing Net Factory. Father of two. list. Wasantha Senanayake SLFP Chief Organiser for Kolonnawa. Barister of Law. Studied at Sajin Vaas Gunawardene Awarded Deshabimana Deshashakthi Janaran- S. Thomas’ Prep. Graduated Born in 1973. WANNI PUTTALAM jana from the National Peace Association. Univ. Buckingham LLB. Prominent business Great grandson of Ceylon’s personality. UPFA UPFA first Prime Minister D. S. SLFP Galle District Senanayake and F.R. Organiser. Noor Mohommed Farook Victory Anthony Perera Thilanga Sumathipala Senanayake. President’s Coordinating Born in 1975. Native of Born in 1949. Born 1964 Secretary.