Sri Lanka 2016 Human Rights Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

As at 28 February 2017

as at 01 M a rch 2017 FESTINA LENTE ADVANCING HUMAN RIGHTS, ACCOUNTABILITY, RECONCILIATION AND GOOD GOVERNANCE IN SRI LANKA January 2015 – March 2017 1 STEP OBSERVATIONS DATE MARCH 2017 Land release The Air Force released 42 acres of private land to the Mullaitivu GA, ending the protests staged by 01 people in front of the Air Force Base since January 2017. March FEBRUARY 2017 Cabinet of Ministers approves compensation Compensation payments proposed by the Minister of Prison Reforms, Rehabilitation, Resettlement 28 payments to those affected and Hindu Religious Affairs, as per the Commission appointed to investigate into the incidents, February by Incidents in Welikada approved by Cabinet. Compensation payments approved for 16 prisoners who passed away (Rs. Prison on 9 November 2012 2,000,000.00 each); and 20 injured (Rs. 500,000.00 each) Examination of Sri Lanka’s Sri Lanka’s 8th Periodic Report under the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of 22 Report to CEDAW Discrimination Against Women examined by the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination February Against Women (CEDAW) Legislation to give effect to The International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance Bill 09 the International Convention was published in the Government Gazette February for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced English: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_E.pdf Disappearance Sinhala: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_S.pdf Tamil: http://documents.gov.lk/files/bill/2017/2/01-2017_T.pdf -

Justice Denied: a Reality Check on Resettlement, Demilitarization, And

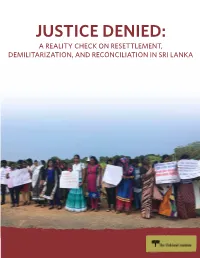

JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA JUSTICE DENIED: A REALITY CHECK ON RESETTLEMENT, DEMILITARIZATION, AND RECONCILIATION IN SRI LANKA Acknowledgements This report was written by Elizabeth Fraser with Frédéric Mousseau and Anuradha Mittal. The views and conclusions expressed in this publication are those of The Oakland Institute alone and do not reflect opinions of the individuals and organizations that have sponsored and supported the work. Cover photo: Inter-Faith Women’s Group in solidarity protest with Pilavu residents, February 2017 © Tamil Guardian Design: Amymade Graphic Design Publisher: The Oakland Institute is an independent policy think tank bringing fresh ideas and bold action to the most pressing social, economic, and environmental issues. Copyright © 2017 by The Oakland Institute. This text may be used free of charge for the purposes of advocacy, campaigning, education, and research, provided that the source is acknowledged in full. The copyright holder requests that all such uses be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, reuse in other publications, or translation or adaptation, permission must be secured. For more information: The Oakland Institute PO Box 18978 Oakland, CA 94619 USA www.oaklandinstitute.org [email protected] Acronyms CID Criminal Investigation Department CPA Centre for Policy Alternatives CTA Counter Terrorism Act CTF Consultation Task Force on Reconciliation Mechanisms IDP Internally Displaced Person ITJP International Truth and Justice Project LTTE Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam OMP Office on Missing Persons PTA Prevention of Terrorism Act UNCAT United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment UNHRC United Nations Human Rights Council 3 www.oaklandinstitute.org Executive Summary In January 2015, Sri Lanka elected a new President. -

*‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups

T5 Table[5.[Ethnic[and[National[Groups T5 T5 TableT5[5. [DeweyEthnici[Decimaand[NationalliClassification[Groups T5 *‡Table 5. Ethnic and National Groups The following numbers are never used alone, but may be used as required (either directly when so noted or through the interposition of notation 089 from Table 1) with any number from the schedules, e.g., civil and political rights (323.11) of Navajo Indians (—9726 in this table): 323.119726; ceramic arts (738) of Jews (—924 in this table): 738.089924. They may also be used when so noted with numbers from other tables, e.g., notation 174 from Table 2 In this table racial groups are mentioned in connection with a few broad ethnic groupings, e.g., a note to class Blacks of African origin at —96 Africans and people of African descent. Concepts of race vary. A work that emphasizes race should be classed with the ethnic group that most closely matches the concept of race described in the work Except where instructed otherwise, and unless it is redundant, add 0 to the number from this table and to the result add notation 1 or 3–9 from Table 2 for area in which a group is or was located, e.g., Germans in Brazil —31081, but Germans in Germany —31; Jews in Germany or Jews from Germany —924043. If notation from Table 2 is not added, use 00 for standard subdivisions; see below for complete instructions on using standard subdivisions Notation from Table 2 may be added if the number in Table 5 is limited to speakers of only one language even if the group discussed does not approximate the whole of the -

In the Court of Appeal of the Democratic Socialist Republic of Sri Lanka

IN THE COURT OF APPEAL OF THE DEMOCRATIC SOCIALIST REPUBLIC OF SRI LANKA In the matter of an application for a mandate in the nature of Writ of Certiorari and Prohibition in terms of Article 140 of the Constitution CA (Writ) Application No: 148 /2012 J. M. Lakshman Jayasekara Director General, National Physical Planning Department 5th Floor, Sethsiti paya, Battaramulla. PETITIONER 1. S.M.Gotabaya Jayarathne, Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla. 1st RESPONDENT 1.A P.H.L. Wimalasiri Perera Secretary, Ministry of Construction, Engineering Services, Housing & Common Amenities, 5th Floor C,Sethsiripaya, Battaramulla Present Secretary ADDED 1A RESPONDENT 2. Vidyajothi Dr. Dayasiri Fernando, Chairman, 3. Palitha Kumarasinghe P.C, Member, 4. Mrs. Sirimavo A. Wijayaratne, Member, 5. Ananda Seneviratne, Member 6. N.H. Pathirana, Member, 7. S. Thillanadarajah, Member, 8. M.B.W. Ariyawansa, Member, 9. M.A.Mohomed Nahiya, Member, 10. P.M.L.C. Seneviratne Secretary, All of Public Services Commission, 177, Nawala Road, Colombo 5. 11. Attorney General Attorney General's department, Colombo 12. 12. Hon. Prime Minister D. M. Jayaratne Ministry of Buddha Sasana & Religious Affairs 13. Hon. Ratnasiri Wickramanayake Ministry of Good Governance & Infrastructure Facilities 14. Hon. D. E. W. Gunasekera Ministry of Human Resources 15. Hon. Athauda Seneviratne Ministry of Rural Affairs 16. Hon. P. Dayaratne Ministry of Food Security 17. Hon. A. H. M. Fowzie Ministry of Urban Affairs 18. Hon. S. B. Navinne Ministry of Consumer Welfare 19. Hon. Piyasena Gamage Ministry of National Resources 20. Hon. (Prof) Tissa Vitharana Ministry of Scientific Affairs 21. -

REFUGEECOSATT3.Pdf

+ + + Refugees and IDPs in South Asia Editor Dr. Nishchal N. Pandey + + Published by Consortium of South Asian Think Tanks (COSATT) www.cosatt.org Konrad Adenauer Stiftung (KAS) www.kas.de First Published, November 2016 All rights reserved Printed at: Modern Printing Press Kathmandu, Nepal. Tel: 4253195, 4246452 Email: [email protected] + + Preface Consortium of South Asian Think-tanks (COSATT) brings to you another publication on a critical theme of the contemporary world with special focus on South Asia. Both the issues of refugees and migration has hit the headlines the world-over this past year and it is likely that nation states in the foreseeable future will keep facing the impact of mass movement of people fleeing persecution or war across international borders. COSATT is a network of some of the prominent think-tanks of South Asia and each year we select topics that are of special significance for the countries of the region. In the previous years, we have delved in detail on themes such as terrorism, connectivity, deeper integration and the environment. In the year 2016, it was agreed by all COSATT member institutions that the issue of refugees and migration highlighting the interlinkages between individual and societal aspirations, reasons and background of the cause of migration and refugee generation and the role of state and non-state agencies involved would be studied and analyzed in depth. It hardly needs any elaboration that South Asia has been both the refugee generating and refugee hosting region for a long time. South Asian migrants have formed some of the most advanced and prosperous diasporas in the West. -

ETHNOGRAPHY in the TIME of CORONA Social Impact of The

1 ETHNOGRAPHY IN THE TIME OF CORONA Social impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in Sri Lanka Sindi Haxhi Student Number: 12757454 [email protected] Supervisor: Dr. Oskar Verkaaik Medical Anthropology and Sociology University of Amsterdam 10 August 2020 2 Acknowledgments Having to do ethnography in such a turbulent time has been an experience that has taught me more about my profession than any class could ever have. Most importantly, it taught me that it is in these uncertain times that people come together to help one another, and this researcher could have never happened without the support of some wonderful people. I would like to take the time here and acknowledge some of these people who have contributed, officially or unofficially, to the final product of my ethnographic work. First of all, this research could have never come to life without the help of my local supervisor, Dr. Ruwan Ranasinghe, as well as the whole Uva Wellassa University. When I arrived in Badulla, it was the day that marked the beginning of the lockdown and the nation-wide curfew, which would become our normality for the next two months. During this time, following the vice-chancellor's decision, Professor Jayantha Lal Ratnasekera, I was offered free accommodation inside the campus as well as free transportation to the city centre for essentials shopping. For the next three months, every staff member at the campus made sure I would feel like home, something so crucial during a time of isolation. Words could never describe how grateful I am to each and every one of them for teaching me the essence of solidarity and hospitality. -

A Commentary on Mitochondrial DNA History of Sri Lankan Ethnic People: Their Relations Within the Island and with the Indian Subcontinental Populations

Journal of Human Genetics (2014) 59, 61–63 & 2014 The Japan Society of Human Genetics All rights reserved 1434-5161/14 www.nature.com/jhg COMMENTARY Language isolates and their genetic identity: a commentary on mitochondrial DNA history of Sri Lankan ethnic people: their relations within the island and with the Indian subcontinental populations Gyaneshwer Chaubey Journal of Human Genetics (2014) 59, 61–63; doi:10.1038/jhg.2013.122; published online 21 November 2013 outh Asia is the home to more than a understanding of their genetic structuring, The first genetic study of Vedda along Sfifth of the world’s population, and is whereas genetic information from Nepal, with other Asian populations suggested thought, on genetic grounds, to have been Bangladesh, Bhutan, Sri Lanka and the their long period of isolation.13 However, the first main reservoir in the dispersal Maldives are either published at the level of the analysis of alpha-2-HS-glycoprotein of modern humans Out of Africa.1,2 forensic data or restricted to few populations. allele frequencies supports the view that Additionally, high level of endogamy within Being at the offshoot of southernmost tip of the Veddas are biologically most closely and between various castes, along with the South Asia and along the proposed southern related to the Sinhalese.14 Till date, a high- influence of several evolutionary forces and migration route, the island of Sri Lanka has resolution genetic data was not available long-term effective population size, facilitate long been settled by various ethnic groups from this population and their affinity with the formation of complex demographic and may offer a unique insight into initial other populations of Eurasia remained 3 history of the subcontinent. -

Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate Jyotsna Shankar Claremont Mckenna College

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont CMC Senior Theses CMC Student Scholarship 2011 Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate Jyotsna Shankar Claremont McKenna College Recommended Citation Shankar, Jyotsna, "Post-Conflict Reconstruction in Sri Lanka and Cyprus: Avoiding a Stalemate" (2011). CMC Senior Theses. Paper 201. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/cmc_theses/201 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you by Scholarship@Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in this collection by an authorized administrator. For more information, please contact [email protected]. CLAREMONT McKENNA COLLEGE POST-CONFLICT RECONSTRUCTION IN SRI LANKA AND CYPRUS: AVOIDING A STALEMATE SUBMITTED TO PROFESSOR BILL ASCHER AND DEAN GREGORY HESS BY JYOTSNA SHANKAR FOR SENIOR THESIS FALL-SPRING/2010-2011 APRIL 12, 2011 ABSTRACT ................................................................................................................. 1 LIST OF ACRONYMS .............................................................................................. 2 CHAPTER ONE: GOALS ......................................................................................... 4 SRI LANKA ................................................................................................................. 4 CYPRUS .................................................................................................................... 11 CHAPTER 2: BACKGROUND AND TRENDS ................................................... 19 -

From Aristocrats to Primitives: an Interview with Gananath Obeyesekere

IIAS | P.O. Box 9515 | 2300 RA Leiden | The Netherlands | T +31-71-527 2227 | F +31-71-527 4162 | [email protected] | www.iias.nl Website: www.IIAS.nl (fragment) <Theme: (1995). Harsh Goenka, Bombay. Bombay. Goenka, Harsh (1995). Psychiatry in Asia Dr. Patels’s Clinic-Lamington Road Clinic-Lamington Patels’s Dr. Atul Dodiya, Dodiya, Atul 30 page 6-11 March 2003 | the IIAS newsletter is published by the IIAS and is available free of charge ¶ p.33 From Aristocrats to Primitives An Interview with Gananath Obeyesekere Gananath Obeyesekere lives on a mountaintop in Kandy. From his eyrie he has a sweeping panorama of the Interview > eastern hills of Sri Lanka, and it is in those hills where the wild Veddas were once supposed to have lived, 7 South Asia according to Sri Lankan histories and stories. These Veddas are the focus of his present research. By Han ten Brummelhuis happened to the Veddas who once lived in this part of the country? he genealogy of Obeyesekere’s research project can be ‘Then, as my fieldwork and thinking progressed, I asked Ttraced back to a classic work, The Veddas, written by myself: if the Veddas were in this vast region north of the area The connection between algebra and Asia is laid bare laid is Asia and algebra between connection The Charles and Brenda Seligmann in 1911. The Veddas were first in which the Seligmanns did their fieldwork, let me figure ¶ recognized in anthropological terms as a classic hunting and out whether they existed in other parts of the country, too. -

The Dhivehi Language. a Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects“ Von Sonja Fritz (2002)

Achtung! Dies ist eine Internet-Sonderausgabe des Buchs „The Dhivehi Language. A Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects“ von Sonja Fritz (2002). Sie sollte nicht zitiert werden. Zitate sind der Originalausgabe zu entnehmen, die als Beiträge zur Südasienforschung, 191 erschienen ist (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag 2002 / Heidelberg: Südasien-Institut). Attention! This is a special internet edition of the book “ The Dhivehi Language. A Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects ” by Sonja Fritz (2002). It should not be quoted as such. For quotations, please refer to the original edition which appeared as Beiträge zur Südasienforschung, 191 (Würzburg: Ergon Verlag 2002 / Heidelberg: Südasien-Institut). Alle Rechte vorbehalten / All rights reserved: Sonja Fritz, Frankfurt 2012 37 The Dhivehi Language A Descriptive and Historical Grammar of Maldivian and Its Dialects by Sonja Fritz Heidelberg 2002 For Jost in love Preface This book represents a revised and enlarged English version of my habilitation thesis “Deskriptive Grammatik des Maledivischen (Dhivehi) und seiner Dialekte unter Berücksichtigung der sprachhistorischen Entwicklung” which I delivered in Heidelberg, 1997. I started my work on Dhivehi (Maldivian) in 1988 when I had the opportunity to make some tape recordings with native speakers during a private stay in the Maldives. Shortly after, when I became aware of the fact that there were almost no preliminary studies of a scientific character on the Maldivian language and literature and, particularly, no systematic linguistic studies at all, I started to collect material for an extensive grammatical description of the Dhivehi language. In 1992, I went to the Maldives again in order to continue my work with informants and to make official contact with the corresponding institutions in M¯ale, whom I asked to help me in planning my future field research. -

Transitional Justice Reconciliation Good Governance Resettlement

Transitional Reconciliation Justice Resettlement Good and Durable Governance Solutions SRI LANKA PEACEBUILDING PRIORITY PLAN August 2016 Overview and Strategic Objective The Peacebuilding Priority Plan (PPP) supports the Government of Sri Lanka to implement its reconciliation and accountability/transitional justice commitments to its people as part of its peacebuilding agenda. The three (3) year comprehensive plan builds on the Government’s ongoing political reforms and the Human Rights Council Resolution of September 2016 which Sri Lanka co- sponsored. The United Nations has been tasked to play a key role in developing and coordinating the implementation of the plan that will also serve as a key tool for coordinating development partners’ support to peacebuilding. The Government of Sri Lanka has put in place institutional structures to deliver on various peacebuilding commitments, with the Secretariat for Coordination of Reconciliation Mechanisms (SCRM) in the Prime Minister Office having the central coordination function. Operationalization of the Plan is guided by the Government’s four (4) Pillars of support of: Transitional Justice; Reconciliation; Good Governance; and Resettlement and Durable Solutions. Funding for the plan will come from various sources including UN, development partners and Government sources. The UN Peacebuilding Fund (PBF) will be strategically positioned to catalyse and leverage the peacebuilding support efforts. Sri Lanka Peacebuilding Priority Plan - Funding Summary Of which: PBF Government Pillar/Strategic Funding Funding Focus Area(s) outcome Need Committed Pledged Gap3 through IRF1 2016 1. Transitional Justice Outcome: 1. Capacity and consultations 2. Truth Telling Government leads a credible, victim- centric process of accountability, 3. Office of Missing Persons 2 2 2 truth-seeking, reparations for past $15.8 $2.7 $2.3 $10.9 4. -

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 25

Sri Lanka Page 1 of 25 Sri Lanka Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2000 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor February 23, 2001 Sri Lanka is a longstanding democratic republic with an active multiparty system. Constitutional power is shared between the popularly elected President and the 225-member Parliament. Chandrika Kumaratunga, head of the governing People's Alliance (PA) coalition, won reelection in 1999 for a second 6-year presidential term in a process marked by voting irregularities and at least six election-related deaths. Violence and fraud marked the October parliamentary elections as well; at least seven persons were killed in campaign-related violence in the period prior to the October election, which resulted in a reduced majority for the PA for the next 6-year period. The Government respects constitutional provisions for an independent judiciary. Through its rulings, the judiciary continued to exhibit its independence and to uphold individual civil rights, although the Supreme Court Chief Justice, in an attempt to reduce the court's workload, limited the fundamental rights cases that the court examined, preventing some torture victims from obtaining redress. For the past 17 years, the Government has fought the Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE), an insurgent organization fighting for a separate ethnic Tamil state in the north and east of the country. The conflict has claimed over 62,000 lives. In 1999 government forces took LTTE-controlled areas north and west of Vavuniya, but counterattacks starting in November 1999 erased most government gains. In January the LTTE began a buildup on the Jaffna peninsula and in April captured the important Elephant Pass military base.