Recentering the Borderlands: Matepe As Sacred Technology from the Mutapa State to the Age of Vapostori

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published Papers of the Ethnomusicology Symposia

International Library of African Music PAPERS PRESENTED AT THE SYMPOSIA ON ETHNOMUSICOLOGY 1ST SYMPOSIUM 1980, RHODES UNIVERSITY (OUT OF PRINT) CONTENTS: The music of Zulu immigrant workers in Johannesburg Johnny Clegg Group composition and church music workshops Dave Dargie Music teaching at the University of Zululand Khabi Mngoma Zulu children’s songs Bongani Mthethwa White response to African music Andrew Tracey 2ND SYMPOSIUM 1981, RHODES UNIVERSITY (OUT OF PRINT) CONTENTS: The development of African music in Zimbabwe Olof Axelsson Towards an understanding of African dance: the Zulu isishameni style Johnny Clegg A theoretical approach to composition in Xhosa style Dave Dargie Music and body control in the Hausa Bori spirit possession cult Veit Erlmann Musical instruments of SWA/Namibia Cecilia Gildenhuys The categories of Xhosa music Deirdre Hansen Audiometric characteristics of the ethnic ear Sean Kierman The correlation of folk and art music among African composers Khabi Mngoma The musical bow in Southern Africa David Rycroft Songs of the Chimurenga: from protest to praise Jessica Sherman The music of the Rehoboth Basters Frikkie Strydom Some aspects of my research into Zulu children’s songs Pessa Weinberg 3RD SYMPOSIUM 1982, UNIVERSITY OF NATAL and 4TH SYMPOSIUM 1983, RHODES UNIVERSITY CONTENTS: The necessity of theory Kenneth Gourlay Music and liberation Dave Dargie African humanist thought and belief Ezekiel Mphahlele Songs of the Karimojong Kenneth Gourlay An analysis of semi-rural and peri-urban Zulu children’s songs Pessa Weinberg -

A Look at the Influence of Celebrity Endorsement on Customer Purchase Intentions: the Case Study of Fast Foods Outlet Companies in Harare, Zimbabwe

Vol. 11(15), pp. 347-356, 14 August, 2017 DOI: 10.5897/AJBM2017.8357 Article Number: 1F480E865441 ISSN 1993-8233 African Journal of Business Management Copyright © 2017 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article http://www.academicjournals.org/AJBM Full Length Research Paper Midas touch or time bomb? A look at the influence of celebrity endorsement on customer purchase intentions: The case study of fast foods outlet companies in Harare, Zimbabwe Jacob Shenje Business Research Consultancy (B.R.C) Pvt Ltd, 5 Rutledge Street, Milton Park Harare, Zimbabwe. Received 14 June, 2017; Accepted 6 July, 2017 Fast foods companies in Zimbabwe have been outcompeting and outclassing each other in using celebrity endorsers for their marketing communications. The study aimed to investigate the impact of celebrity endorsement on consumer purchase intentions. The study’s literature review was based on a copious of celebrity endorsement empirical and theoretical literature. The literature review also acted as bedrock for the research methodology which was later adopted. In order to achieve the research objectives, the study was largely quantitative where survey questionnaires were distributed to customers and these questionnaires were useful in the aggregation of the results. The findings were entered into SPSS software package version 22. The result shows that celebrity endorsement variables showed a positive and significant statistical relationship with consumer buying intentions. The study recommends for fast foods companies to gauge the capacity of celebrities to project multi-attributes which would be consistent and of interest to the consumer’s requirements. There is also the need to strengthen certain aspects of celebrity consumer relationship as way of understanding the implications for product endorsement in the fast foods industry. -

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian

Creating a Roadmap for the Future of Music at the Smithsonian A summary of the main discussion points generated at a two-day conference organized by the Smithsonian Music group, a pan- Institutional committee, with the support of Grand Challenges Consortia Level One funding June 2012 Produced by the Office of Policy and Analysis (OP&A) Contents Acknowledgements .................................................................................................................................. 3 Introduction ................................................................................................................................................ 4 Background ............................................................................................................................................ 4 Conference Participants ..................................................................................................................... 5 Report Structure and Other Conference Records ............................................................................ 7 Key Takeaway ........................................................................................................................................... 8 Smithsonian Music: Locus of Leadership and an Integrated Approach .............................. 8 Conference Proceedings ...................................................................................................................... 10 Remarks from SI Leadership ........................................................................................................ -

A History of the Pacific Islands

A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS I. C. Campbell A HISTORY OF THE PACIFIC ISLANDS Thi s One l N8FG-03S-LXLD A History of the Pacific Islands I. C. CAMPBELL University of California Press Berkeley • Los Angeles Copyrighted material © 1989 I. C. Campbell Published in 1989 in the United States of America by the University of California Press Berkeley and Los Angeles All rights reserved. Apart from any fair use for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, no part whatsoever may by reproduced by any process without the express written permission of the author and the University of California Press. Library of Congress Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Campbell, LC. (Ian C), 1947- A history of the Pacific Islands / LC. Campbell, p. cm. "First published in 1989 by the University of Canterbury Press, Christchurch, New Zealand" — T.p. verso. Includes bibliographical references. ISBN 0-520-06900-5 (alk. paper). — ISBN 0-520-06901-3 (pbk. alk. paper) 1. Oceania — History. I. Title DU28.3.C35 1990 990 — dc20 89-5235 CIP Typographic design: The Caxton Press, Christchurch, New Zealand Cover design: Max Hailstone Cartographer: Tony Shatford Printed by: Kyodo-Shing Loong Singapore C opy righted m ateri al 1 CONTENTS List of Maps 6 List of Tables 6 A Note on Orthography and Pronunciation 7 Preface. 1 Chapter One: The Original Inhabitants 13 Chapter Two: Austronesian Colonization 28 Chapter Three: Polynesia: the Age of European Discovery 40 Chapter Four: Polynesia: Trade and Social Change 57 Chapter Five: Polynesia: Missionaries and Kingdoms -

THE HISTORY of the TONGA and FISHING COOPERATIVES in BINGA DISTRICT 1950S-2015

FACULTY OF ARTS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY EMPOWERMENT OR CONTROL? : THE HISTORY OF THE TONGA AND FISHING COOPERATIVES IN BINGA DISTRICT 1950s-2015 BY HONOUR M.M. SINAMPANDE R131722P DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF ARTS IN PARTIAL FULLFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS OF THE HONOURS DEGREE IN HISTORY AT MIDLANDS STATE UNIVERSITY. NOVEMBER 2016 ZVISHAVANE: ZIMBABWE SUPERVISOR DR. T.M. MASHINGAIDZE APPROVAL FORM The undersigned certify that they have supervised the student Honour M.M Sinampande (R131722P) dissertation entitled Empowerment or Control? : The history of the Tonga and fishing cooperatives in Binga District 1950-210 submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Bachelor of Arts in History Honours Degree offered by Midlands State University. Dr. T.M Mashingaidze ……………………… SUPERVISOR DATE …….……………………………………… …………………………….. CHAIRPERSON DATE ….………………………………………… …………………………….. EXTERNAL EXAMINER DATE DECLARATION I, Honour M.M Sinampande declare that, Empowerment or Control? : The history of the Tonga and fishing cooperatives in Binga District 1950s-2015 is my own work and it has never been submitted before any degree or examination in any other university. I declare that all sources which have been used have been acknowledged. I authorize the Midlands State University to lend this to other institution or individuals for purposes of academic research only. Honour M.M Sinampande …………………………………………… 2016 DEDICATION This work is dedicated to my father Mr. H.M Sinampande and my mother Ms. J. Muleya for their inspiration, love and financial support throughout my four year degree programme. ABSTRACT The history of the Tonga have it that, the introduction of the fishing villages initially and then later the cooperative system in Binga District from the 1950s-2015 saw the Zambezi Tonga lose their fishing rights. -

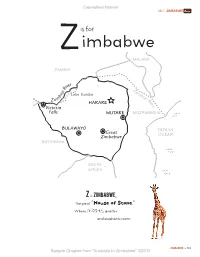

Z Is for Zimbabwe – Sample Chapter from Book

Copyrighted Material MEET ZIMBABWE! is for Zimbabwe MALAWI Z ZAMBIA a m b e z i r R ive i v R Z e i a r z m e Lake Kariba b b ez m i Za Ri NAMIBIA HARARE ve Victoria r Falls MUTARE MOZAMBIQUE BULAWAYO Great INDIAN Zimbabwe OCEAN BOTSWANA SOUTH AFRICA Z is Zimbabwe, the great “House of Stone,” Where zebras, giraffes and elephants roam. ZIMBABWE 311 Sample Chapter from "Australia to Zimbabwe" ©2015 Copyrighted Material MEET ZIMBABWE! Here you can hear the mbira’s soft sounds [em-BEER-rah] Calling the ancestors Mbira out of the ground. (Thumb Piano) Here Victoria Falls Victoria Falls from the river Zambezi, [zam-BEE-zee] “Mosi oa Tunya” And across the plateau, the weather is easy. Here men find great sculptures hidden in stones, Stone Sculpture Near fields where tobacco and cotton are grown. But their food is from corn Cotton served with sauce (just like pasta) – For breakfast there’s bota, for dinner there’s sadza. Once a colony British called Southern Rhodesia, Sadza This nation was founded on historic amnesia Bota 312 ZIMBABWE Sample Chapter from "Australia to Zimbabwe" ©2015 Copyrighted Material MEET ZIMBABWE! Brits believed civilization arrived with the whites, Who soon took the best land and had all the rights. Cecil Rhodes Rhodesia’s Founder They couldn’t believe Great Zimbabwe had been Great Zimbabwe Constructed by locals – by those with black skin. This fortress in ruins from medieval times Bird Sculpture from Had been city and home Great Zimbabwe to a culture refined. White settlers built cities Great Zimbabwe and farms in this place, And blacks became second class due to their race. -

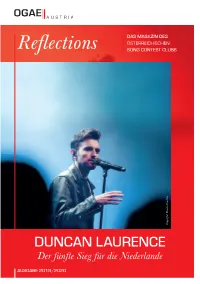

Reflections 3 Reflections

3 Refl ections DAS MAGAZIN DES ÖSTERREICHISCHEN Refl ections SONG CONTEST CLUBS AUSGABE 2019/2020 AUSGABE | TAUSEND FENSTER Der tschechische Sänger Karel Gott („Und samkeit in der großen Stadt beim Eurovision diese Biene, die ich meine, die heißt Maja …“) Song Contest 1968 in der Royal Albert Hall wurde vor allem durch seine vom böhmischen mit nur 2 Punkten den bescheidenen drei- SONG CONTEST CLUBS Timbre gekennzeichneten, deutschsprachigen zehnten Platz, fi ndet aber bis heute großen Schlager in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren zum Anklang innerhalb der ESC-Fangemeinde. Liebling der Freunde eingängiger U-Musik. Neben der deutschen Version, nahm Karel Copyright: Martin Krachler Ganz zu Beginn seiner Karriere wurde er Gott noch eine tschechische Version und zwei ÖSTERREICHISCHEN vom Österreichischen Rundfunk eingela- englische Versionen auf. den, die Alpenrepublik mit der Udo Jürgens- Hier seht ihr die spanische Ausgabe von „Tau- DUNCAN LAURENCE Komposition „Tausend Fenster“ zu vertreten. send Fenster“, das dort auf Deutsch veröff ent- Zwar erreichte der Schlager über die Ein- licht wurde. MAGAZINDAS DES Der fünfte Sieg für die Niederlande DIE LETZTE SEITE | ections Refl AUSGABE 2019/2020 2 Refl ections 4 Refl ections 99 Refl ections 6 Refl ections IMPRESSUM MARKUS TRITREMMEL MICHAEL STANGL Clubleitung, Generalversammlung, Organisation Clubtreff en, Newsletter, Vorstandssitzung, Newsletter, Tickets Eurovision Song Contest Inlandskorrespondenz, Audioarchiv [email protected] Fichtestraße 77/18 | 8020 Graz MARTIN HUBER [email protected] -

Fair Use As Cultural Appropriation

Fair Use as Cultural Appropriation Trevor G. Reed* Over the last four decades, scholars from diverse disciplines have documented a wide variety of cultural appropriations from Indigenous peoples and the harms these have inflicted. Copyright law provides at least some protection against appropriations of Indigenous culture— particularly for copyrightable songs, dances, oral histories, and other forms of Indigenous cultural creativity. But it is admittedly an imperfect fit for combatting cultural appropriation, allowing some publicly beneficial uses of protected works without the consent of the copyright owner under certain exceptions, foremost being copyright’s fair use doctrine. This Article evaluates fair use as a gatekeeping mechanism for unauthorized uses of copyrighted culture, one which empowers courts to sanction or disapprove of cultural appropriations to further copyright’s goal of promoting creative production. DOI: https://doi.org/10.15779/Z38V97ZS35. Copyright © 2021 Trevor G. Reed * Trevor Reed (Hopi) is an Associate Professor of Law at Arizona State University’s Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law. The author thanks June Besek, Bruce Boyden, Christine Haight Farley, Eric Goldman, Rhett Larson, Jake Linford, Jon Kappes, Kali Murray, Guy Rub, Troy Rule, Erin Scharff, Joshua Sellers, Michael Selmi, Justin Weinstein-Tull, and Andrew Woods for their helpful feedback on this project. The author also thanks Qiaoqui (Jo) Li, Elizabeth Murphy, Jillian Bauman, M. Vincent Amato and Isaac Kort-Meade for their research assistance. Early versions of this paper were presented at, and received helpful feedback from, the 2019 Race + IP conference, faculty colloquia at the University of Arizona and University of Washington, the American Association for Law School’s annual meeting, and the American Library Association’s CopyTalk series. -

Human Rights for Musicians Freemuse

HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS FREEMUSE – The World Forum on Music and Censorship Freemuse is an international organisation advocating freedom of expression for musicians and composers worldwide. OUR MAIN OBJECTIVES ARE TO: • Document violations • Inform media and the public • Describe the mechanisms of censorship • Support censored musicians and composers • Develop a global support network FREEMUSE Freemuse Tel: +45 33 32 10 27 Nytorv 17, 3rd floor Fax: +45 33 32 10 45 DK-1450 Copenhagen K Denmark [email protected] www.freemuse.org HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS HUMAN RIGHTS FOR MUSICIANS Ten Years with Freemuse Human Rights for Musicians: Ten Years with Freemuse Edited by Krister Malm ISBN 978-87-988163-2-4 Published by Freemuse, Nytorv 17, 1450 Copenhagen, Denmark www.freemuse.org Printed by Handy-Print, Denmark © Freemuse, 2008 Layout by Kristina Funkeson Photos courtesy of Anna Schori (p. 26), Ole Reitov (p. 28 & p. 64), Andy Rice (p. 32), Marie Korpe (p. 40) & Mik Aidt (p. 66). The remaining photos are artist press photos. Proofreading by Julian Isherwood Supervision of production by Marie Korpe All rights reserved CONTENTS INTRODUCTION Human rights for musicians – The Freemuse story Marie Korpe 9 Ten years of Freemuse – A view from the chair Martin Cloonan 13 PART I Impressions & Descriptions Deeyah 21 Marcel Khalife 25 Roger Lucey 27 Ferhat Tunç 29 Farhad Darya 31 Gorki Aguila 33 Mahsa Vahdat 35 Stephan Said 37 Salman Ahmad 41 PART II Interactions & Reactions Introducing Freemuse Krister Malm 45 The organisation that was missing Morten -

Hard Oktober 2018

MIT ANRUFBUS- GEWINNSPIEL! Seite 12 hard 10/18 04 Schule am See Stimmungsvoller Festakt zur Eröffnung 06 Rundes Jubiläum Feuerwehrjugend Hard feiert „50er“ 09 VCÖ Mobilitätspreis 2018 Projekt „Selbstständig zur Schule“ ausgezeichnet 12 Gewinnspiel Mit dem Anrufbus gratis nach Hause 15 Lehrlingstag Hard Erfolgreiche Premiere 18 Projekt „Zeitpolster“ Ein neues Vorsorgesystem stellt sich vor 19 Für den guten Zweck Flohmarkt im ehemaligen Alma-Gebäude 03 Editorial hard 10/18 „Zu ihrem 50-jährigen Jubiläum wünsche ich der Jugendfeuerwehr alles Gute!“ Liebe Harderinnen und Harder! Mit der Fertigstellung der „Schule am See“ haben wir einen bedeutenden Schritt gesetzt, die bestmögliche pädagogische Betreuung für unsere Kinder auch künftig sicherzustellen. Rund 42,5 Mio. Euro wurden in das größte Infrastrukturprojekt in der Geschichte unserer Gemeinde und damit in die Zukunft inves- tiert. Entsprechend groß war das Interesse an der feierlichen Eröffnung am 15. September. Tausende Harderinnen und Harder nutzten die Möglichkeit, sich an diesem Tag durch das zukunfts- orientierte Schulzentrum führen zu lassen und sich vor Ort von den vielen Vorzügen des Neubaus zu überzeugen. Ich bedanke mich an dieser Stelle herzlich bei allen Bürgerinnen und Bürgern für das große Interesse an unserer neuen Schule und für das große Lob und die Anerkennung, die uns entgegengebracht wurden. Gleichzeitig möchte ich die Gelegenheit nutzen und all jenen danken, die mit ihrem großen Einsatz dazu beigetragen haben, dass die Eröffnung so erfolgreich verlaufen ist. Die Mitglieder der Ortsfeuerwehr Hard leisten einen unent- behrlichen Beitrag zum Gemeindeleben und tragen mit ihrem ehrenamtlichen Einsatz wesentlich zu unserer Sicherheit und zu unserem Wohl bei. Damit dies so bleibt, ist es wichtig, junge Menschen als Nachwuchs zu gewinnen. -

THE ORIGINAL AFRICAN MBIRA? (See Map)

A/-^ <-*■*■*. g , 2 ' A 9 -1-2. THE ORIGINAL AFRICAN MBIRA ? THE ORIGINAL AFRICAN MBIRA? h §§* ANDREW TRACEY ft may be possible to show, one day, that all the different mbiras1 of Africa are descended from one another, and that all stem from one particular type, which can then te assumed to be the form of the instrument as it was originally invented. I would like D present here some evidence to show that in one large part of Africa at least all the ■any types of mbiras can be traced back, with greater or lesser degrees of probability, IB one type which must, at least, be very ancient, and at most, if connections with, or distribution to other mbira areas of Africa can be proved, may be the nearest we will get to knowing the earliest form of the mbira in Africa. The area comprises most of Rhodesia, central Mozambique, and southern and eastern and parts of southern Malawi, southern Mozambique, and northern Transvaal, >m Zunbia, Sooth Africa. Or, to put it more simply, much of the lower Zambezi valley, with a spill ell ire ant towards the south (see map). tl On first considering the bewildering variety of different types of mbiras played in this m, taking into account the different reed arrangements, methods of construction, tone anilities and musical techniques, it is hard to find any consistent family relationships. Bat if only one feature is taken as the main indicator, namely the arrangement of the •otei in the keyboard, which, as it appears, turns out to be a remarkably constant factor, Kreral interesting and far-reaching relationships come to light. -

Swierstra's Francolin Francolinus Swierstrai

abcbul 28-070718.qxp 7/18/2007 2:05 PM Page 175 Swierstra’s Francolin Francolinus swierstrai: a bibliography and summary of specimens Michael S. L. Mills Le Francolin de Swierstra Francolinus swierstrai: bibliographie et catalogue des spécimens. Le Francolin de Swierstra Francolinus swierstrai, endémique aux montagnes de l’Angola occidental, est considérée comme une espèce menacée (avec le statut de ‘Vulnérable’). En l’absence d’obser- vations entre 1971 et 2005, nous connaissons très peu de choses sur cette espèce. Cette note résume l’information disponible, basée sur 19 spécimens récoltés de 1907 à 1971, et présente une bibliographie complète, dans l’espoir d’encourager plus de recherches sur l’espèce. Summary. Swierstra’s Francolin Francolinus swierstrai is the only threatened bird endemic to the montane region of Western Angola. With no sightings between 1971 and August 2005, knowl- edge of this species is very poor. This note presents a summary of available information, based on 19 specimens collected between 1907 and 1971, and provides a complete bibliography, in order to encourage further work on this high-priority species. wierstra’s Francolin Francolinus swierstrai (or SSwierstra’s Spurfowl Pternistis swierstrai) was last recorded in February 1971 (Pinto 1983), until its rediscovery at Mt Moco in August 2005 (Mills & Dean in prep.). This Vulnerable species (BirdLife International 2000, 2004) is the only threatened bird endemic to montane western Angola, an area of critical importance for biodiver- sity conservation (Bibby et al. 1992, Stattersfield et al. 1998). Swierstra’s Francolin has a highly fragmented range of c.18,500 km2 and is suspected, despite the complete lack of sightings for more than 30 years, to have a declining population estimated at 2,500–9,999.