Virtual Book Ends Café at Featuring

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018-0000023

LETTRE CIRCULAIRE n° 2018-0000023 Montreuil, le 03/08/2018 DRCPM OBJET Sous-direction production, Bénéficiaires du versement transport (art. L. 2333-64 et s. du Code gestion des comptes, Général des Collectivités Territoriales) fiabilisation Texte(s) à annoter : VLU-grands comptes et VT LCIRC-2018-0000005 Affaire suivie par : ANGUELOV Nathalie, Changement d'adresse du Syndicat Mixte des Transports Urbains de la BLAYE DUBOIS Nadine, Sambre (9305904) et (93059011). WINTGENS Claire Le Syndicat Mixte des Transports Urbains de la Sambre (9305904) et (9305911) nous informe de son changement d’adresse. Toute correspondance doit désormais lui être envoyée à l’adresse suivante : 4, avenue de la Gare CS 10159 59605 MAUBEUGE CEDEX Les informations relatives au champ d’application, au taux, au recouvrement et au reversement du versement transport sont regroupées dans le tableau ci-joint. 1/1 CHAMP D'APPLICATION DU VERSEMENT TRANSPORT (Art. L. 2333-64 et s. du Code Général des Collectivités Territoriales) SMTUS IDENTIFIANT N° 9305904 CODE DATE COMMUNES CONCERNEES CODE POSTAL TAUX URSSAF INSEE D'EFFET - ASSEVENT 59021 59600, 59604 - AULNOYE-AYMERIES 59033 59620 - BACHANT 59041 59138 - BERLAIMONT 59068 59145 - BOUSSIERES-SUR-SAMBRE 59103 59330 - BOUSSOIS 59104 59168, 59602 - COLLERET 59151 59680 - ECLAIBES 59187 59330 - ELESMES 59190 59600 - FEIGNIES 59225 59606, 59307, 59750, 59607 - FERRIERE-LA-GRANDE 59230 59680 - FERRIERE-LA-PETITE 59231 59680 - HAUTMONT 59291 59618, 59330 1,80 % 01/06/2009 NORD-PAS-DE- CALAIS - JEUMONT 59324 59572, 59573, 59460, -

L'assainissement Collectif En Sambre Avesnois

L'assainissement collectif en Sambre Avesnois Les gestionnaires en charge de L’assainissement coLLectif En Sambre Avesnois, l’assainissement partie de l’Agglomération Maubeuge Val sont réunies au sein du Syndicat Inter- collectif est pour une grande majorité des de Sambre (AMVS), qui délègue au SMVS communal d’Assainissement Fourmies- communes (près de 80 %) assuré par le cette compétence. Un règlement d’assai- Wignehies (SIAFW), qui délègue Syndicat Mixte SIDEN-SIAN et sa Régie nissement spécifique s’impose dans les l’assainissement à la société Eau et Force. NOREADE. communes de l’AMVS, permettant ainsi Enfin, les communes de Beaurepaire-sur- SCOTLe Sambre-AvesnoisSyndicat Mixte Val de Sambre (SMVS) d’assurer un meilleur rendement du Sambre et Boulogne sur Helpe gèrent est chargé de la compétence assainisse- traitement des eaux usées. directement leur assainissement en régie Structuresment de compétentes 28 communes, dont et ( 22ou font ) gestionnaires Deux communes, de Fourmies l’assainissement et Wignehies, collectifcommunale, sans passer par un syndicat. structures compétentes et (ou) gestionnaires de L’assainissement coLLectif Houdain- Villers-Sire- lez- Nicole Gussignies Bavay Bettignies Hon- Hergies Gognies- Eth Chaussée Bersillies Vieux-Reng Bettrechies Taisnières- Bellignies sur-Hon Mairieux Bry Jenlain Elesmes Wargnies- La Flamengrie le-Grand Saint-Waast Feignies Jeumont Wargnies- (communeSaint-Waast isolée) Boussois le-Petit Maresches Bavay Assevent Marpent La LonguevilleLa Longueville Maubeuge Villers-Pol Preux-au-Sart (commune -

Die Neufassung Des § 1A Bundesversorgungsgesetz (BVG): Streichung Von Kriegsopferrenten Für NS-Täter – Schlussbericht –

FORSCHUNGSBERICHT 472 Die Neufassung des § 1a Bundesversorgungsgesetz (BVG): Streichung von Kriegsopferrenten für NS-Täter – Schlussbericht – November 2016 ISSN 0174-4992 Die Neufassung des § 1a Bundesversorgungsgesetz (BVG): Streichung von Kriegsopferrenten für NS-Täter - Gründe für die geringe Zahl der Streichungen trotz der Vielzahl der vom Simon Wiesenthal Center übermittelten Daten - Ein Gemeinschaftsprojekt des Bundesministeriums für Arbeit und Soziales und des Simon Wiesenthal Centers Schlussbericht September 2016 2 Die Neufassung des § 1a Bundesversorgungsgesetz (BVG): Streichung von Kriegsopferrenten für NS-Täter - Gründe für die geringe Zahl der Streichungen trotz der Vielzahl der vom Simon Wiesenthal Center übermittelten Daten - Ein Gemeinschaftsprojekt des Bundesministeriums für Arbeit und Soziales und des Simon Wiesenthal Centers Schlussbericht Autoren: Dr. Stefan Klemp (Simon Wiesenthal Center) Martin Hölzl (Simon Wiesenthal Center) Ort: Bonn im September 2016 ISBN/ISSN: Auftraggeberschaft / Inhaltliche Verantwortung Erstellt im Auftrag des Bundesministeriums für Arbeit und Soziales. Die Durchführung der Untersuchungen sowie die Schlussfolgerungen aus den Unter- suchungen sind von den Auftragnehmern in eigener wissenschaftlicher Verantwor- tung vorgenommen worden. Das Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales über- nimmt insbesondere keine Gewähr für die Richtigkeit, Genauigkeit und Vollständig- keit der Untersuchungen. Copyright Alle Rechte einschließlich der fotomechanischen Wiedergabe und des auszugswei- sen Nachdrucks -

Gis'death Toll Rises at the Same Time a State Department Spokesman Prod- SAIGON (AP) - the Num- U.S

gfam SEE STORY BELOW Windy Cold, windy with chance' of HOME few snow flurries today. Hed Bank, Freehold f Clearing, colder tonight and tomorrow. Long Branch J FINAL -1 (Bet Settlla Pag» 2) Monmouth County's Home Newspaper for 90 Years VOL. 91, NO. 114 RED BANK, N. J., THURSDAY, DECEMBER 5,1968 46 PAGfS TEN CENTS U.S. Presses for Mideast Peace By JOHN M. HIGHTOWER article which touches on a not had evidence of compar- dor Abdul Hamid Sharaf were cern," McCloskey said, "over Israeli and Jordanian repre- WASHINGTON (AP) - The number pf points," McClos- able Soviet exertions in the summoned separately to the the situation in the Middle sentatives in New York and to United States is trying ur- key said. "What we are look- interest of peace. State Department Wednesday East presently. Violations of take the same line with them. gently through diplomatic ing for, however, is concrete Arms to Both afternoon and told of deep the cease-fire line by either JJ.N. Special Envoy Gunner pressure to prevent further evidence that the Soviets are The United States itself is U.S. concern over events in or both sides serve only to Jarring has recently arrived ' escalation of the Israel-Arab exerting their influence to- supplying arms to both Israel the Mideast. heighten tensions in the area in Cairo on a new round of and hinder the efforts of the border • clashes which have ward peace in the Middle and Jordan, which has tradi- U.S. officials indicated the peace making activities fol- intensified the Middle East East. -

Chesterfield Wfa

CHESTERFIELD WFA Newsletter and Magazine issue 28 Patron –Sir Hew Strachan FRSE FRHistS President - Professor Peter Simkins MBE Welcome to Issue 28 - the April 2018 FRHistS Newsletter and Magazine of Chesterfield WFA. Vice-Presidents Andre Colliot Professor John Bourne BA PhD FRHistS The Burgomaster of Ypres The Mayor of Albert Lt-Col Graham Parker OBE Professor Gary Sheffield BA MA PhD FRHistS Christopher Pugsley FRHistS Lord Richard Dannat GCB CBE MC rd DL Our next meeting will be on Tuesday April 3 where our guest speaker will be the Peter Hart, no stranger to Roger Lee PhD jssc the Branch making his annual pilgrimage back to his old www.westernfrontassociation.com home town. Branch contacts Peter`s topic will be` Not Again` - the German Tony Bolton offensive on the Aisne, May 1918. ` (Chairman) anthony.bolton3@btinternet .com Mark Macartney The Branch meets at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, (Deputy Chairman) Chesterfield S40 1NF on the first Tuesday of each month. There [email protected] is plenty of parking available on site and in the adjacent road. Access to the car park is in Tennyson Road, however, which is Jane Lovatt (Treasurer) one way and cannot be accessed directly from Saltergate. Grant Cullen (Secretary) [email protected] Grant Cullen – Branch Secretary Facebook http://www.facebook.com/g roups/157662657604082/ http://www.wfachesterfield.com/ Western Front Association Chesterfield Branch – Meetings 2018 Meetings start at 7.30pm and take place at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, Chesterfield S40 1NF January 9th Jan.9th Branch AGM followed by a talk by Tony Bolton (Branch Chairman) on the key events of the last year of the war 1918. -

Central Europe

Central Europe Federal Republic of Germany Domestic Affairs J.N THE DOMESTIC SPHERE, 1981 and 1982 saw growing problems for the government coalition consisting of the Social Democratic party (SPD) and the Free Democratic party (FDP). Finally, on October 1, 1982, the government fell in a no-confidence vote—the first time this had occurred in the post-World War II period. The new coalition that assumed office was made up of the Christian Demo- cratic Union (CDU) and the Christian Social Union (CSU), with the participation of the FDP; Chancellor Helmut Kohl headed the new coalition. There was a further decline in the economy in 1983—1981 and 1982 had been marked by economic recession—although the situation began to stabilize toward the end of the year. The change of government was confirmed by the public in the general elections held on March 6, 1983: the CDU-CSU won 48.8 per cent of the vote; the SPD 38.2 per cent; and the FDP 7.0 per cent, just narrowly escaping elimination from the Bundestag. The Greens, a party supported by a variety of environmentalist and pacifist groups, entered the federal parliament for the first time, having won 5.6 per cent of the vote. One of the leading representatives of the Greens, Werner Vogel, returned his mandate after an internal party dispute con- cerning his Nazi past. The peace movement and the Greens, often seconded by the SPD, were extremely critical of the policy of Western military strength advocated by the Reagan adminis- tration in Washington. More than half a million people participated in a series of peaceful demonstrations against nuclear weapons in October. -

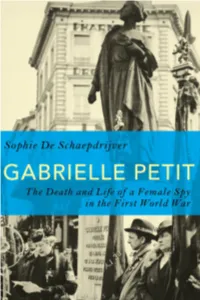

Gabrielle Petit

GABRIELLE PETIT i ii GABRIELLE PETIT THE DEATH AND LIFE OF A FEMALE SPY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR S o p h i e D e S c h a e p d r i j v e r Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc iii Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Sophie De Schaepdrijver, 2015 Sophie De Schaepdrijver has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author. British Library Cataloguing- in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4725-9087-9 PB: 978-1-4725-9086-2 ePDF: 978-1-4725-9088-6 ePub: 978-1-4725-9089-3 Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Schaepdrijver, Sophie de. Gabrielle Petit : the death and life of a female spy in the First World War / Sophie De Schaepdrijver. -

LISTE-DES-ELECTEURS.Pdf

CIVILITE NOM PRENOM ADRESSE CP VILLE N° Ordinal MADAME ABBAR AMAL 830 A RUE JEAN JAURES 59156 LOURCHES 62678 MADAME ABDELMOUMEN INES 257 RUE PIERRE LEGRAND 59000 LILLE 106378 MADAME ABDELMOUMENE LOUISA 144 RUE D'ARRAS 59000 LILLE 110898 MONSIEUR ABU IBIEH LUTFI 11 RUE DES INGERS 07500 TOURNAI 119015 MONSIEUR ADAMIAK LUDOVIC 117 AVENUE DE DUNKERQUE 59000 LILLE 80384 MONSIEUR ADENIS NICOLAS 42 RUE DU BUISSON 59000 LILLE 101388 MONSIEUR ADIASSE RENE 3 RUE DE WALINCOURT 59830 WANNEHAIN 76027 MONSIEUR ADIGARD LUCAS 53 RUE DE LA STATION 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 116892 MONSIEUR ADONEL GREGORY 84 AVENUE DE LA LIBERATION 59300 AULNOY LEZ VALENCIENNES 12934 CRF L'ESPOIR DE LILLE HELLEMMES 25 BOULEVARD PAVE DU MONSIEUR ADURRIAGA XIMUN 59260 LILLE 119230 MOULIN BP 1 MADAME AELVOET LAURENCE CLINIQUE DU CROISE LAROCHE 199 RUE DE LA RIANDERIE 59700 MARCQ EN BAROEUL 43822 MONSIEUR AFCHAIN JEAN-MARIE 43 RUE ALBERT SAMAIN 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 35417 MADAME AFCHAIN JACQUELINE 267 ALLEE CHARDIN 59650 VILLENEUVE D ASCQ 35416 MADAME AGAG ELODIE 137 RUE PASTEUR 59700 MARCQ EN BAROEUL 71682 MADAME AGIL CELINE 39 RUE DU PREAVIN LA MOTTE AU BOIS 59190 MORBECQUE 89403 MADAME AGNELLO SYLVIE 77 RUE DU PEUPLE BELGE 07340 colfontaine 55083 MONSIEUR AGNELLO CATALDO Centre L'ADAPT 121 ROUTE DE SOLESMES BP 401 59407 CAMBRAI CEDEX 55082 MONSIEUR AGOSTINELLI TONI 63 RUE DE LA CHAUSSEE BRUNEHAUT 59750 FEIGNIES 115348 MONSIEUR AGUILAR BARTHELEMY 9 RUE LAMARTINE 59280 ARMENTIERES 111851 MONSIEUR AHODEGNON DODEME 2 RUELLE DEDALE 1348 LOUVAIN LA NEUVE - Belgique121345 MONSIEUR -

1815, WW1 and WW2

Episode 2 : 1815, WW1 and WW2 ‘The Cockpit of Europe’ is how Belgium has understatement is an inalienable national often been described - the stage upon which characteristic, and fame is by no means a other competing nations have come to fight reliable measure of bravery. out their differences. A crossroads and Here we look at more than 50 such heroes trading hub falling between power blocks, from Brussels and Wallonia, where the Battle Belgium has been the scene of countless of Waterloo took place, and the scene of colossal clashes - Ramillies, Oudenarde, some of the most bitter fighting in the two Jemappes, Waterloo, Ypres, to name but a World Wars - and of some of Belgium’s most few. Ruled successively by the Romans, heroic acts of resistance. Franks, French, Holy Roman Empire, Burgundians, Spanish, Austrians and Dutch, Waterloo, 1815 the idea of an independent Belgium nation only floated into view in the 18th century. The concept of an independent Belgian nation, in the shape that we know it today, It is easy to forget that Belgian people have had little meaning until the 18th century. been living in these lands all the while. The However, the high-handed rule of the Austrian name goes back at least 2,000 years, when Empire provoked a rebellion called the the Belgae people inspired the name of the Brabant Revolution in 1789–90, in which Roman province Gallia Belgica. Julius Caesar independence was proclaimed. It was brutally was in no doubt about their bravery: ‘Of all crushed, and quickly overtaken by events in these people [the Gauls],’ he wrote, ‘the the wake of the French Revolution of 1789. -

Sommaire P.6

3 P.4 SOMMAIRE P.6 HÔTELS P.4 LOCATIONS MEUBLÉes CLÉVACANCes P.6 LOCATIONS MEUBLÉes TOURISTIQUes CLASSÉes P.9 LOCATIONS MEUBLÉes NON CLASSÉES OU EN COURS DE CLASSEMENT P.14 GÎTES RURAUX P.16 CHAMBRES D’HÔTES P.18 CAMPINGS P.20 gîtes DE SÉJOUR P.21 P.20 Si vous constatez des erreurs ou modifications, merci d’en informer l’Office de Tourisme de La Porte du Hainaut. 4 HÔTELS 5 Hôtels classés ★ ★ ★ Hôtel classé ★ ★ AKENA CITY ★ ★ ★ LE FORESTIER ★ ★ 59 chambres 8 chambres / Capacité : 14 personnes / Restaurant : 200 couverts Situé à 3 km des Thermes, 800 m du Pasino, 3 km du centre-ville et 150 m du cinéma, À l’orée et au calme de la forêt dans un site privilégié, à 300 m des Thermes. l’hôtel Akena City vous accueille 7 jours sur 7 de 6 h à 23 h. Les 59 chambres dont 3 Salle de bain, douche et WC dans les chambres, parking privé, accès wifi gratuit, chambres pour personnes à mobilité réduite sont entièrement équipées et climatisées téléphone, mini-coffre, terrasse, jeux pour enfants dans le parc. Restaurant : cuisine avec salle de bain privative, TV écran plat (canal+, canal sat), ascenseur, parking gratuit régionale et traditionnelle (spécialités maison), formules à partir de 15€, menus et carte. Zone artisanale du Mont des et sécurisé. Restaurants à proximité et très prochainement formule soirée étape. 1648 A, route de la Fontaine Bouillon Tarifs : 57€ (lit double) et 65€ (lits jumeaux). Bruyères - Rocade Nord Nouveau : venez découvrir la carte fidélité ! 59230 Saint-Amand-les-Eaux Petit déjeuner : 6,90€. -

Living with the Enemy in First World War France

i The experience of occupation in the Nord, 1914– 18 ii Cultural History of Modern War Series editors Ana Carden- Coyne, Peter Gatrell, Max Jones, Penny Summerfield and Bertrand Taithe Already published Carol Acton and Jane Potter Working in a World of Hurt: Trauma and Resilience in the Narratives of Medical Personnel in Warzones Julie Anderson War, Disability and Rehabilitation in Britain: Soul of a Nation Lindsey Dodd French Children under the Allied Bombs, 1940– 45: An Oral History Rachel Duffett The Stomach for Fighting: Food and the Soldiers of the First World War Peter Gatrell and Lyubov Zhvanko (eds) Europe on the Move: Refugees in the Era of the Great War Christine E. Hallett Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War Jo Laycock Imagining Armenia: Orientalism, Ambiguity and Intervention Chris Millington From Victory to Vichy: Veterans in Inter- War France Juliette Pattinson Behind Enemy Lines: Gender, Passing and the Special Operations Executive in the Second World War Chris Pearson Mobilizing Nature: the Environmental History of War and Militarization in Modern France Jeffrey S. Reznick Healing the Nation: Soldiers and the Culture of Caregiving in Britain during the Great War Jeffrey S. Reznick John Galsworthy and Disabled Soldiers of the Great War: With an Illustrated Selection of His Writings Michael Roper The Secret Battle: Emotional Survival in the Great War Penny Summerfield and Corinna Peniston- Bird Contesting Home Defence: Men, Women and the Home Guard in the Second World War Trudi Tate and Kate Kennedy (eds) -

Magazine Municipal D'information

magazine municipal d’information n° 79 - Novembre 2018 http://www.louvroil.fr AGENDA LOCAL DÉCEMBRE JANVIER FÉVRIER Du vendredi 7 au dimanche 9 Jeudi 10 Samedi 9 Marché de Noël, Spectacle Ben et Arnaud Tsamère "Enfin sur scène" Concert "La ballade des gens heureux", • Espace Casadesus. "Yann Guillarme fout le bordel", • Espace Culturel Casadesus. • 20h00, Espace Culturel Casadesus. Tarif unique 10€. Du samedi 8 au dimanche 9, Tarif abonné 30€. Tarif réduit 34€. Tarif plein 36€. & du mardi 11 au vendredi 14 Vendredi 11 Expo-vente Playmobil, • Médiathèque George Sand. Vœux à la population, • 18h00, salle Casadesus. MARS Vendredi 14 décembre Du vendredi 18 au dimanche 20 Ballades culinaires, • Espace Culturel Casadesus. Adam Naas+Yorina. Spectacle participatif « Espèces de trucs en trocs ». Dimanche 10 • Théâtre à l’Espace Culturel Casadesus. Tarif abonné 6€. Tarif plein 10€. Foulées de Louvroil. Gratuit pour les moins de 6 ans. Gratuit sur réservations. Dimanche 27 Musique du monde dans le cadre des balades culinaires "Bonbon vodou + guest". • Tarif abonné 6€. Tarif plein 10€. Gratuit pour les moins de 6 ans. LE NOËL DU CONSERVATOIRE DÉCEMBRE 2018 Lundi 17 à 18h30 : Concert par les classes d’atelier jazz et orchestre à cordes. Mardi 18 à 18h00 : Conte de Noël par les classes de Théâtre Enfants, l’orchestre à vents, l’ensemble des percussions et l’ensemble de guitare. Mercredi 19 à 18h00 : Concert par les classes d’éveil et PDI, les chorales Enfants/Adultes et la classe de chant. Jeudi 20 à 18h30 : Concert par les classes de piano et accordéon. COMMÉMORATION du 11 novembre Comme partout en France, le centenaire de la fin du premier conflit mondial a été célébré ce dimanche 11 novembre à Louvroil.