Bereavement and Mourning (Belgium)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chesterfield Wfa

CHESTERFIELD WFA Newsletter and Magazine issue 28 Patron –Sir Hew Strachan FRSE FRHistS President - Professor Peter Simkins MBE Welcome to Issue 28 - the April 2018 FRHistS Newsletter and Magazine of Chesterfield WFA. Vice-Presidents Andre Colliot Professor John Bourne BA PhD FRHistS The Burgomaster of Ypres The Mayor of Albert Lt-Col Graham Parker OBE Professor Gary Sheffield BA MA PhD FRHistS Christopher Pugsley FRHistS Lord Richard Dannat GCB CBE MC rd DL Our next meeting will be on Tuesday April 3 where our guest speaker will be the Peter Hart, no stranger to Roger Lee PhD jssc the Branch making his annual pilgrimage back to his old www.westernfrontassociation.com home town. Branch contacts Peter`s topic will be` Not Again` - the German Tony Bolton offensive on the Aisne, May 1918. ` (Chairman) anthony.bolton3@btinternet .com Mark Macartney The Branch meets at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, (Deputy Chairman) Chesterfield S40 1NF on the first Tuesday of each month. There [email protected] is plenty of parking available on site and in the adjacent road. Access to the car park is in Tennyson Road, however, which is Jane Lovatt (Treasurer) one way and cannot be accessed directly from Saltergate. Grant Cullen (Secretary) [email protected] Grant Cullen – Branch Secretary Facebook http://www.facebook.com/g roups/157662657604082/ http://www.wfachesterfield.com/ Western Front Association Chesterfield Branch – Meetings 2018 Meetings start at 7.30pm and take place at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, Chesterfield S40 1NF January 9th Jan.9th Branch AGM followed by a talk by Tony Bolton (Branch Chairman) on the key events of the last year of the war 1918. -

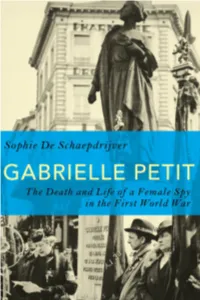

Gabrielle Petit

GABRIELLE PETIT i ii GABRIELLE PETIT THE DEATH AND LIFE OF A FEMALE SPY IN THE FIRST WORLD WAR S o p h i e D e S c h a e p d r i j v e r Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc iii Bloomsbury Academic An imprint of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc 50 Bedford Square 1385 Broadway London New York WC1B 3DP NY 10018 UK USA www.bloomsbury.com BLOOMSBURY and the Diana logo are trademarks of Bloomsbury Publishing Plc First published 2015 © Sophie De Schaepdrijver, 2015 Sophie De Schaepdrijver has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identifi ed as Author of this work. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage or retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publishers. No responsibility for loss caused to any individual or organization acting on or refraining from action as a result of the material in this publication can be accepted by Bloomsbury or the author. British Library Cataloguing- in-Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. ISBN: HB: 978-1-4725-9087-9 PB: 978-1-4725-9086-2 ePDF: 978-1-4725-9088-6 ePub: 978-1-4725-9089-3 Library of Congress Cataloging- in-Publication Data Schaepdrijver, Sophie de. Gabrielle Petit : the death and life of a female spy in the First World War / Sophie De Schaepdrijver. -

1815, WW1 and WW2

Episode 2 : 1815, WW1 and WW2 ‘The Cockpit of Europe’ is how Belgium has understatement is an inalienable national often been described - the stage upon which characteristic, and fame is by no means a other competing nations have come to fight reliable measure of bravery. out their differences. A crossroads and Here we look at more than 50 such heroes trading hub falling between power blocks, from Brussels and Wallonia, where the Battle Belgium has been the scene of countless of Waterloo took place, and the scene of colossal clashes - Ramillies, Oudenarde, some of the most bitter fighting in the two Jemappes, Waterloo, Ypres, to name but a World Wars - and of some of Belgium’s most few. Ruled successively by the Romans, heroic acts of resistance. Franks, French, Holy Roman Empire, Burgundians, Spanish, Austrians and Dutch, Waterloo, 1815 the idea of an independent Belgium nation only floated into view in the 18th century. The concept of an independent Belgian nation, in the shape that we know it today, It is easy to forget that Belgian people have had little meaning until the 18th century. been living in these lands all the while. The However, the high-handed rule of the Austrian name goes back at least 2,000 years, when Empire provoked a rebellion called the the Belgae people inspired the name of the Brabant Revolution in 1789–90, in which Roman province Gallia Belgica. Julius Caesar independence was proclaimed. It was brutally was in no doubt about their bravery: ‘Of all crushed, and quickly overtaken by events in these people [the Gauls],’ he wrote, ‘the the wake of the French Revolution of 1789. -

14-18. Les Monuments Racontent : 14-18

14-18. CLASSES DU PATRIMOINE & DE LA CITOYENNETÉ CLASSES DU PATRIMOINE & DE LA CITOYENNETÉ Les monuments racontent Dans le cadre de la commémoration de la Première Guerre mondiale, les Classes du Patrimoine & de la Citoyenneté ont développé un parcours interactif sur tablette (14-18 : Bruxelles occupée) et un premier cahier pédagogique, tous deux consacrés à la vie quotidienne à Bruxelles pendant ces quatre années d’occupation. Ce deuxième cahier aborde la Première Guerre mondiale sous l’angle de la commémoration. Il vous invite à sortir de la classe avec vos élèves pour décoder les monuments commémoratifs. Que signifie cette fleur ? Pourquoi ce personnage se tient-il droit ? Que tient-il dans la main ? Pourquoi ses vêtements sont-ils si anguleux ? Et où trouver un monument à proximité de l’école ? Ce cahier se veut un outil pratique, il vous propose de multiples angles d’approche pour tenter de comprendre le message laissé par les personnes qui ont vécu la Grande Guerre. Ce deuxième volume s’accompagne d’exemples concrets à télécharger sur notre site. Il s’agit de fiches d’observation clé sur porte consacrées à certains monuments-phares de la Région. Vous pouvez les utiliser telles quelles ou vous en inspirer pour créer votre propre fiche. Qui sommes-nous ? 14-18. Les monuments racontent monuments Les 14-18. Les Classes du patrimoine & de la Citoyenneté, un programme de la Région de Bruxelles- Capitale, / 02 organisent depuis 2005 des activités destinées aux élèves des écoles bruxelloises pour découvrir le patrimoine de la Région sur un mode actif et citoyen. Nous proposons également sur notre site (classesdupatrimoine.be) des dossiers pédagogiques pour préparer ou prolonger nos animations ou encore partir à la découverte du patrimoine en toute autonomie. -

Monument À Gabrielle Petit - (15) - Page 1 |

(15) En pratique Thèmes abordés Situation : place St-Jean - 1000 Bruxelles - plan Les femmes pendant la guerre Accès : Quelques notions de mode féminine - Métros 1 & 5 - arrêt Gare Centrale - Bus 48 & 95 - arrêt Parlement bruxellois Les actes patriotiques Pour une lisibilité optimale, agrafez le carnet dans La représentation allégorique l’angle supérieur gauche. Non loin de là… Contenu Le Monument à l’infanterie (10) Le Monument de la reconnaissance Les réponses aux fiches d’observation des britannique à la population belge (11) élèves (en bleu). Quelques propositions de questions supplémentaires pour initier un échange oral (dans les cadres bleus). En fin de fiche, une conclusion structurée par thème (situation, matériaux, inscriptions…) à partager avec vos élèves. Libre à vous de sélectionner l’information que vous estimez la plus pertinente. L’important est avant tout d’amener vos élèves à observer. Vous trouverez l’ensemble des fiches d’observation sur : https://www.classesdupatrimoine.brussels/dossiers-pedagogiques/14-18-les- monuments-racontent/ 14-18 - Monument à Gabrielle Petit - (15) - page 1 | 2) Coche tout ce qui en fait partie. Monument à Gabrielle Petit La situation du monument un plusieurs personnage personnages 1) Décris la situation du monument en cochant ce que tu vois. On peut le voir de loin On n’a pas de recul pour bien le voir On peut en faire le tour Il est placé contre un mur L’espace autour est bien dégagé Il y a des bâtiments tout autour un socle un piédestal un obélisque Il est situé dans un lieu fréquenté Il est situé dans un endroit isolé. -

The First World War Commemorations in the Brussels-Capital Region 2014-18Brussels.Be

The First World War commemorations in the Brussels-Capital Region 2014-18brussels.be 1 Brussels and the First World War During the First World War, Brussels was the sole European capital that was made to endure the long years of the occupation. Unlike other parts of the country, Brussels did not suffer any major battles or ravages. But that did not make the impact of the war any less on the Brussels residents: the rationing and the goods and properties that were commandee- red made their mark on people’s everyday lives. Ci- tizens got involved in the war effort, by tending to the wounded, but some also took up arms against the occupier by joining the resistance. As such, some of these men and women went down in history as he- roes. With the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier, the ca- pital of Brussels is the only location where national homage is paid to the victims of the First World War. It is important that we keep alive the memory of what the war entailed: how was life in a town under mili- tary occupation and what kind of impact did the war have on society in the early part of the 20th century? The commemorations of the First World War in the Brussels Capital Region are a good opportunity to draw attention to the timeless nature of values such as free- dom, solidarity, social cohesion, fatherland, indepen- dence and democracy, which were central to this first worldwide conflict. This is why the Great War should forever remain a foundation of tomorrow’s democracy. -

The Traces of World War I in Brussels BSI Synopsis Sur Les Traces De La Première Guerre Mondiale À Bruxelles

Brussels Studies La revue scientifique électronique pour les recherches sur Bruxelles / Het elektronisch wetenschappelijk tijdschrift voor onderzoek over Brussel / The e-journal for academic research on Brussels Notes de synthèse | 2016 The traces of World War I in Brussels BSI synopsis Sur les traces de la Première Guerre mondiale à Bruxelles. Note de synthèse BSI In de sporen van de Eerste Wereldoorlog in Brussel. BSI synthesenota Serge Jaumain, Virginie Jourdain, Michaël Amara, Bruno Benvindo, Pierre Bouchat, Eric Bousmar, Arnaud Charon, Thierry Eggerickx, Elisabeth Gybels, Chantal Kesteloot, Olivier Klein, Benoît Mihail, Sven Steffens, Pierre-Alain Tallier, Nathalie Tousignant and Joost Vaesen Translator: Jane Corrigan Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/brussels/1420 DOI: 10.4000/brussels.1420 ISSN: 2031-0293 Publisher Université Saint-Louis Bruxelles Electronic reference Serge Jaumain, Virginie Jourdain, Michaël Amara, Bruno Benvindo, Pierre Bouchat, Eric Bousmar, Arnaud Charon, Thierry Eggerickx, Elisabeth Gybels, Chantal Kesteloot, Olivier Klein, Benoît Mihail, Sven Steffens, Pierre-Alain Tallier, Nathalie Tousignant and Joost Vaesen, « The traces of World War I in Brussels », Brussels Studies [Online], Synopses, no 102, Online since 04 July 2016, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/brussels/1420 ; DOI : 10.4000/brussels.1420 Licence CC BY www.brusselsstudies.be www.brusselsstudiesinstitute.be the e-journal for academic research on Brussels the platform for research on Brussels Number 102, July 4th 2016. ISSN 2031-0293 Serge Jaumain, Virginie Jourdain, et al. BSI synopsis. The traces of World War I in Brussels Translation: Jane Corrigan Serge Jaumain is a professor of contemporary history and vice-rector of Virginie Jourdain has a doctorate in contemporary history from Université international relations at Université libre de Bruxelles. -

Virtual Book Ends Café at Featuring

VIRTUAL BOOK ENDS CAFÉ AT FEATURING BOOK SUMMARY In an enthralling new historical novel from national bestselling author Kate Quinn, two women --- a female spy recruited to the real-life Alice Network in France during World War I and an unconventional American socialite searching for her cousin in 1947 --- are brought together in a mesmerizing story of courage and redemption. 1947. In the chaotic aftermath of World War II, American college girl Charlie St. Clair is pregnant, unmarried, and on the verge of being thrown out of her very proper family. She's also nursing a desperate hope that her beloved cousin Rose, who disappeared in Nazi-occupied France during the war, might still be alive. So when Charlie's parents banish her to Europe to have her "little problem" taken care of, Charlie breaks free and heads to London, determined to find out what happened to the cousin she loves like a sister. 1915. A year into the Great War, Eve Gardiner burns to join the fight against the Germans and unexpectedly gets her chance when she's recruited to work as a spy. Sent into enemy-occupied France, she's trained by the mesmerizing Lili, the "Queen of Spies," who manages a vast network of secret agents right under the enemy's nose. Thirty years later, haunted by the betrayal that ultimately tore apart the Alice Network, Eve spends her days drunk and secluded in her crumbling London house. Until a young American barges in uttering a name Eve hasn't heard in decades, and launches them both on a mission to find the truth...no matter where it leads. -

Be Heritage Be . Brussels

HISTORY HERITAGE DAYS AND MEMORY 20 & 21 SEPT. 2014 be heritage be . brussels Info Featured pictograms Organisation of Heritage Days in Brussels-Capital Region: Regional Public Service of Brussels/Brussels Urban Development Opening hours and dates Department of Monuments and Sites a CCN – Rue du Progrès/Vooruitgangsstraat 80 – 1035 BRUSSELS Telephone helpline open on 20 and 21 September from 10h00 to 17h00: M Metro lines and stops 02/204.17.69 – Fax: 02/204.15.22 – www.heritagedaysbrussels.be [email protected] – #jdpomd – Bruxelles Patrimoines – Erfgoed Brussel T Trams The times given for buildings are opening and closing times. In case of large crowds, the organisers reserve the right to close the doors earlier in order to finish at the foreseen time. B Bus Smoking, eating and drinking is prohitited and in certain buildings the taking of photographs is not allowed either. Walking Tour/Activity “Listed” at the end of notices indicates the date on which the property described g was listed or registered on the list of protected buildings. The coordinates indicated at the top in color refer to a map of the Region. h Exhibition/Conference A free copy of this map can be requested by writing to the Department of Monuments and Sites. Bicycle Tour Information relating to public transport serving the sites was provided by STIB. b It indicates the closest stops to the sites or starting points and the lines served on Saturdays and Sundays. Music Please note that advance bookings are essential for certain tours (reservation ♬ number indicated below the notice). This measure has been implemented for the sole purpose of accommodating the public under the best possible conditions i Guided tour only or and ensuring that there are sufficient guides available. -

The Traces of World War I in Brussels BSI Synopsis Sur Les Traces De La Première Guerre Mondiale À Bruxelles

Brussels Studies La revue scientifique électronique pour les recherches sur Bruxelles / Het elektronisch wetenschappelijk tijdschrift voor onderzoek over Brussel / The e-journal for academic research on Brussels 2016 Notes de synthèse | 2016 The traces of World War I in Brussels BSI synopsis Sur les traces de la Première Guerre mondiale à Bruxelles. Note de synthèse BSI In de sporen van de Eerste Wereldoorlog in Brussel. BSI synthesenota Serge Jaumain, Virginie Jourdain, Michaël Amara, Bruno Benvindo, Pierre Bouchat, Eric Bousmar, Arnaud Charon, Thierry Eggerickx, Elisabeth Gybels, Chantal Kesteloot, Olivier Klein, Benoît Mihail, Sven Steffens, Pierre-Alain Tallier, Nathalie Tousignant and Joost Vaesen Translator: Jane Corrigan Publisher Université Saint-Louis Bruxelles Electronic version URL: http://brussels.revues.org/1420 DOI: 10.4000/brussels.1420 ISSN: 2031-0293 Electronic reference Serge Jaumain, Virginie Jourdain, Michaël Amara, Bruno Benvindo, Pierre Bouchat, Eric Bousmar, Arnaud Charon, Thierry Eggerickx, Elisabeth Gybels, Chantal Kesteloot, Olivier Klein, Benoît Mihail, Sven Steffens, Pierre-Alain Tallier, Nathalie Tousignant and Joost Vaesen, « The traces of World War I in Brussels », Brussels Studies [Online], Synopses, no 102, Online since 04 July 2016, connection on 24 January 2017. URL : http://brussels.revues.org/1420 ; DOI : 10.4000/brussels.1420 The text is a facsimile of the print edition. Licence CC BY www.brusselsstudies.be www.brusselsstudiesinstitute.be the e-journal for academic research on Brussels the platform for research on Brussels Number 102, July 4th 2016. ISSN 2031-0293 Serge Jaumain, Virginie Jourdain, et al. BSI synopsis. The traces of World War I in Brussels Translation: Jane Corrigan Serge Jaumain is a professor of contemporary history and vice-rector of Virginie Jourdain has a doctorate in contemporary history from Université international relations at Université libre de Bruxelles. -

Dossier Monuments Aux Morts Et Aux Héros De La

N°011- 012 NUMERO SPECIAL - SEPTEMBRE 2014 journées du Patrimoine Région de Bruxelles-Capitale D o s s i e r HISTOIRE ET MéMOIRE p L U s Expérience photographique internationale des Monuments Une pUBLicAtion De BrUXeLLes DéVeLoppeMent UrBAin MonUMents AUX Morts et AUX Héros De LA pAtrie ossier l’Héritage D commémoratif des deux guerres mondiales à Bruxelles Benoît MiHAiL ConserVaTeur Du musÉe De la PolIce IntégrÉe Monument à la Gloire de l’infanterie belge, place poelaert à Bruxelles, 1935 (A. de Ville de Goyet, 2013 © sprB). LE PATriMOINE COMMÉMORATIF liÉ AUX DEUX GUErrES MONDIALES EST PARTICUliÈREMENT riCHE EN RÉGION BRUXEllOISE. D’une part, chaque commune possède au moins un monument aux morts – soldats, déportés et civils exécutés – d’autre part, la fonction de capitale de Bruxelles explique la présence de nombreux monuments thématiques liés à une profession ou un héros de la guerre. La qualité des monuments est à l’image de la diversité des talents qui les ont réalisés. Si le style reste souvent marqué par la tradition académique, certains se distinguent par leur force expressive ou une interaction réussie avec leur environnement, ce qui n’apparaît plus toujours aujourd’hui, à cause des nombreux bouleversements urbanistiques postérieurs. les monuments aux morts occupent n’a, en terme de traces de commé- dance ont leur mémorial dès 1838. une place particulière dans l’histoire moration, rien à envier ni aux autres après la guerre franco-prussienne du patrimoine. longtemps dédaignés capitales, ni à des villes d’ampleur de 1870, le cimetière de Bruxelles se par les amateurs d’art, en raison de comparable, comme anvers ou lille, couvre d’imposants monuments aux leur appartenance à une esthétique qui ont pourtant subi la guerre de soldats français, allemands et même académique jugée dépassée, ils doi- manière plus directe.