The First World War Commemorations in the Brussels-Capital Region 2014-18Brussels.Be

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Une «Flamandisation» De Bruxelles?

Une «flamandisation» de Bruxelles? Alice Romainville Université Libre de Bruxelles RÉSUMÉ Les médias francophones, en couvrant l'actualité politique bruxelloise et à la faveur des (très médiatisés) «conflits» communautaires, évoquent régulièrement les volontés du pouvoir flamand de (re)conquérir Bruxelles, voire une véritable «flamandisation» de la ville. Cet article tente d'éclairer cette question de manière empirique à l'aide de diffé- rents «indicateurs» de la présence flamande à Bruxelles. L'analyse des migrations entre la Flandre, la Wallonie et Bruxelles ces vingt dernières années montre que la population néerlandophone de Bruxelles n'est pas en augmentation. D'autres éléments doivent donc être trouvés pour expliquer ce sentiment d'une présence flamande accrue. Une étude plus poussée des migrations montre une concentration vers le centre de Bruxelles des migrations depuis la Flandre, et les investissements de la Communauté flamande sont également, dans beaucoup de domaines, concentrés dans le centre-ville. On observe en réalité, à défaut d'une véritable «flamandisation», une augmentation de la visibilité de la communauté flamande, à la fois en tant que groupe de population et en tant qu'institution politique. Le «mythe de la flamandisation» prend essence dans cette visibilité accrue, mais aussi dans les réactions francophones à cette visibilité. L'article analyse, au passage, les différentes formes que prend la présence institutionnelle fla- mande dans l'espace urbain, et en particulier dans le domaine culturel, lequel présente à Bruxelles des enjeux particuliers. MOTS-CLÉS: Bruxelles, Communautés, flamandisation, migrations, visibilité, culture ABSTRACT DOES «FLEMISHISATION» THREATEN BRUSSELS? French-speaking media, when covering Brussels' political events, especially on the occasion of (much mediatised) inter-community conflicts, regularly mention the Flemish authorities' will to (re)conquer Brussels, if not a true «flemishisation» of the city. -

Phase 2 : Analyse De L'offre Et De La Demande

BRUXELLES ENVIRONNEMENT Développement d’une stratégie globale de redéploiement du sport dans les espaces verts en Région de Bruxelles-Capitale Phase 2 : Analyse de l’offre et la demande Octobre 2017 1 Bruxelles Environnement – Développement d’une stratégie globale de redéploiement du sport dans les espaces verts en Région de Bruxelles-Capitale Document de travail - Phase 2 – Analyse de l’offre et la demande – Octobre 2017 Table des matières Introduction........................................................................................................................................4 A. Analyse par sport ........................................................................................................................5 1. Méthodologie de l’analyse quantitative ...................................................................................5 1.1. Carte de couverture spatiale par sport .............................................................................9 1.2. Carte de priorisation des quartiers d’intervention par sport .............................................9 2. Méthodologie de l’analyse qualitative ................................................................................... 15 3. Principales infrastructures présentes ..................................................................................... 18 3.1. Pétanque ....................................................................................................................... 18 3.2. Football ........................................................................................................................ -

A La Découverte De L'histoire D'ixelles

Yves de JONGHE d’ARDOYE, Bourgmestre, Marinette DE CLOEDT, Échevin de la Culture, Paul VAN GOSSUM, Échevin de l’Information et des Relations avec le Citoyen et les membres du Collège échevinal vous proposent une promenade: À LA DÉCOUVERTE DE L’HISTOIRE D’IXELLES (3) Recherches et rédaction: Michel HAINAUT et Philippe BOVY Documents d’archives et photographies: Jean DE MOYE, Michel HAINAUT, Jean-Louis HOTZ, Emile DELABY et les Collections du Musée communal d’Ixelles. ONTENS D OSTERWYCK Réalisation: Laurence M ’O Entre les deux étangs, Alphonse Renard pose devant la maison de Blérot (1914). Ce fascicule a été élaboré en collaboration avec: LE CERCLE D’HISTOIRE LOCALE D’IXELLES asbl (02/515.64.11) Si vous souhaitez recevoir les autres promenades de notre série IXELLES-VILLAGE ET LE QUARTIER DES ÉTANGS Tél.: 02/515.61.90 - Fax: 02/515.61.92 du lundi au vendredi de 9h à 12h et de 14h à 16h Éditeur responsable: Paul VAN GOSSUM, Échevin de l’Information - avril 1998 Cette troisième promenade est centrée sur les abords de la place Danco, le pianiste de jazz Léo Souris et le chef d’orchestre André Flagey et des Étangs. En cours de route apparaîtront quelques belles Vandernoot. Son fils Marc Sevenants, écrivain et animateur, mieux réalisations architecturales représentatives de l’Art nouveau. Elle connu sous le nom de Marc Danval, est sans conteste le spécialiste ès permettra de replonger au cœur de l’Ixelles des premiers temps et jazz et musique légère de notre radio nationale. Comédien de forma- mettra en lumière l’une des activités économiques majeures de son tion, il avait débuté au Théâtre du Parc dans les années ‘50 et profes- histoire, la brasserie. -

Charles De Broqueville Réalisé Par L’Illustration En 1931, Le Comte Avec Sa Signature

Portrait offi ciel de Charles de Broqueville réalisé par L’illustration en 1931, Le comte avec sa signature. Offi cieel portret van Charles de Broqueville door « L’illustration » in 1931, Graaf Charles met zijn handtekening. de Broqueville Postel-Mol, 4 décembre Bruxelles, 5 septembre Postel-Mol, 4 december 1860 – Brussel, 5 september 1940 Lettre du 28 mai 1913 d’Albert Ier à Charles de Broqueville Brief van 28 mei 1913 van Albert I aan Charles de Broqueville, publié dans un article de La Libre Belgique du 24-25 avril gepubliceerd in een artikel van « La Libre Belgique » van 1965 page 2, à l’occasion de l’inauguration du monument 24-25 april 1965 blz 2, ter gelegenheid van de onthulling Broqueville, par le prince Albert. van het Broqueville-monument door prins Albert. 1860-1914 Charles de Broqueville, fi ls 1860-1914 Charles de Broqueville was aîné du baron Stanislas et de la comtesse Marie-Claire de oudste zoon van baron Stanislas en gravin Marie-Claire de Briey, passa son enfance dans le domaine familial de de Briey en bracht zijn jeugd door op het familiedomein Postel en Campine. te Postel in de Kempen. En 1885, son mariage avec la baronne Berthe d’Huart Zijn huwelijk met barones Berthe d’Huart in 1885 intro- l’introduisit dans la famille de Jules Malou. duceerde hem in de familie van Jules Malou. Il entra très tôt dans la vie publique. Conseiller communal Charles de Broqueville trad al heel vroeg toe tot de politiek. de Mol à vingt-cinq ans, conseiller provincial d’Anvers en Op vijfentwintigjarige leeftijd was hij gemeenteraadslid …ce peuple, même s’il était vaincu, 1886, il fut élu député de Turnhout en 1892. -

Conseil Des Ministres. Procès-Verbaux Des Réunions

BE-A0510_002392_003402_FRE Notulen van de Ministerraad/Procès-verbaux du Conseil des Ministres (1916-1949). Agenda's en aanwezigheidslijsten/Ordres du jour et listes de présence (5.II.1916- 21.V.1931) / L. Verachten Het Rijksarchief in België Archives de l'État en Belgique Das Staatsarchiv in Belgien State Archives in Belgium This finding aid is written in French. 2 Conseil des Ministres. Procès-verbaux des réunions DESCRIPTION DU FONDS D'ARCHIVES:................................................................3 DESCRIPTION DES SÉRIES ET DES ÉLÉMENTS.........................................................5 Gouvernement Charles de Broqueville - 1916.................................................5 Gouvernement Charles de Broqueville - 1917...............................................20 Gouvernement Charles de Broqueville - 1918...............................................26 Gouvernement Gerard Cooreman - 1918.......................................................32 Gouvernement Léon Delacroix I - 1918.........................................................43 Gouvernement Léon Delacroix I - 1919.........................................................48 Gouvernement Léon Delacroix II - 1919........................................................69 Gouvernement Henry Carton de Wiart - 1920...............................................70 Gouvernement Léon Delacroix II - 1920........................................................74 Gouvernement Georges Theunis I - 1921......................................................88 Gouvernement -

Chapter 23: War and Revolution, 1914-1919

The Twentieth- Century Crisis 1914–1945 The eriod in Perspective The period between 1914 and 1945 was one of the most destructive in the history of humankind. As many as 60 million people died as a result of World Wars I and II, the global conflicts that began and ended this era. As World War I was followed by revolutions, the Great Depression, totalitarian regimes, and the horrors of World War II, it appeared to many that European civilization had become a nightmare. By 1945, the era of European domination over world affairs had been severely shaken. With the decline of Western power, a new era of world history was about to begin. Primary Sources Library See pages 998–999 for primary source readings to accompany Unit 5. ᮡ Gate, Dachau Memorial Use The World History Primary Source Document Library CD-ROM to find additional primary sources about The Twentieth-Century Crisis. ᮣ Former Russian pris- oners of war honor the American troops who freed them. 710 “Never in the field of human conflict was so much owed by so many to so few.” —Winston Churchill International ➊ ➋ Peacekeeping Until the 1900s, with the exception of the Seven Years’ War, never ➌ in history had there been a conflict that literally spanned the globe. The twentieth century witnessed two world wars and numerous regional conflicts. As the scope of war grew, so did international commitment to collective security, where a group of nations join together to promote peace and protect human life. 1914–1918 1919 1939–1945 World War I League of Nations World War II is fought created to prevent wars is fought ➊ Europe The League of Nations At the end of World War I, the victorious nations set up a “general associa- tion of nations” called the League of Nations, which would settle interna- tional disputes and avoid war. -

How Did the First World War Start?

How Did the First World War Start? The First World War, often called The Great War, was an enormous and devastating event in the early 1900s. Over 17 million people were killed and it had a massive effect on politics and countries all over the world. But why did the First World War happen and what caused it? The major catalyst for the start of the First World War was the assassination of a man named Archduke Franz Picture associated with the arrest of Gavrilo Princip Ferdinand. However, there were other events which led to the start of the war. The start of the 1900s in Europe was a time of peace for many. In most places, wealth was growing and people were comfortable and countries were thriving. At this time, some European countries, mainly France and Britain, owned and controlled countries in Asia and Africa, as well as some areas of other continents. This was because these countries helped to improve the wealth of Europe. Before the First World War, many countries were allies with one another and they had defence treaties. This meant that if war was declared on one of the countries, the other members of the alliance had to go to war to help them. There were two main alliances, one between Britain, France and Russia called ‘The Triple Entente’ and one between Germany and Austria-Hungary called ‘The Central Powers’. One of the reasons for these treaties was that, during the early 1900s, each country wanted to be the most powerful. Germany in particular, who did not control many territories, began building warships as they wished to become the most powerful country. -

Un Intellectuel En Politique La Plume Et La Voix

Paul-F. Smets PAUL HYMANS Un intellectuel en politique La plume et la voix Préface de Marc Quaghebeur, administrateur délégué des Archives et Musée de la Littérature Cet ouvrage est honoré d’une contribution de la SA TEMPORA et de la SPRL ADMARA. Qu’elles en soient chaleureusement remer- ciées, comme doivent l’être LES ARCHIVES ET MUSÉE DE LA LITTÉRATURE, coéditeur. La couverture du livre reproduit un fragment du portrait de Paul Hymans par Isidore OPSOMER (1935). Collection Pierre Goldschmidt, photographie d’Alice Piemme Mise en page: MC Compo, Liège Toute reproduction ou adaptation d’un extrait quelconque de ce livre, par quelque procédé que ce soit, est interdite pour tous pays. © Éditions Racine, 2016 Tour et Taxis, Entrepôt royal 86C, avenue du Port, BP 104A • B - 1000 Bruxelles D. 2016, 6852. 25 Dépôt légal: novembre 2016 ISBN 978-2-87386-998-4 Imprimé aux Pays-Bas La culture est une joie et une force. Paul Hymans Il y a dans le monde et qui marche parallèlement à la force de mort et de contrainte une force énorme de persuasion qui s’appelle la culture. Albert Camus PRÉFACE Marc Quaghebeur Pour le cent cinquantième anniversaire de la naissance de Paul Hymans, Paul-F. Smets a consacré à cet homme politique majeur du règne d’Albert Ier une remarquable biographie. Son sous-titre était parti culièrement bien choisi: «Un authentique homme d’État». À travers une construction originale faite de brèves séquences, son récit mêle subtilement, et de façon très vivante, l’histoire d’une personnalité et d’une époque capitales pour le pays. -

While the Above Information Provides a General Description of the Yser

While the above information provides a general description of the Yser Medal, it does not convey a sense of the excitement and importance surround- ing the event it commemorates. The Yser Battle was not just another battle; it was a battle of significance for the history of Belgium and the First World War, and cannot be overestimated. In this fight, the battered remnants of the Belgian Field Army, under Albert, King of the Belgians, turned on their Germanic tormentors and made a heroic defensive stand, redeeming Belgian honor, protecting a s~mall corner of Belgium, and assuring an ulti- mately victorious Belgium as a functioning ally of France and England. Following the battle, or more properly, the "maneuver" of the Marne in September 191~, the Allied and German armies probed for the open flank of each other in a series of running battles known to history as the "Race to the Sea", September-November, 191~. The failure of either side to gain the desired flanking position, ultimately doomed all to the attrition of potential trench warfare uutil the spring of 1918. The First Battle of Ypres, of which the Yser Battle was a part, represented the last attempt by the Germans to turn the Allied flank and secure the quick and decisive victory demanded by their original War Plans. They hurled 15 fresh regular and reserve infantry divisions into the battle. It was inadequate; the Allied line held. The Battle of Yser took place on the extreme left of the Allied Front. The Belgians held the lines from the North Sea Coast just north of Nie~port, along the banks of the Yser river, to D~_~nude, Belgium, a towa which was held by the French. -

Germany Austria-Hungary Russia France Britain Italy Belgium

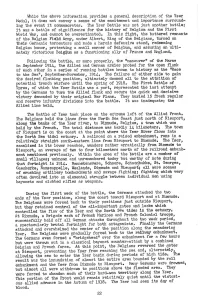

Causes of The First World War Europe 1914 Britain Russia Germany Belgium France Austria-Hungary Serbia Italy Turkey What happened? The incident that triggered the start of the war was a young Serb called Gavrilo Princip shooting the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. Gavrilo Princip Franz Ferdinand This led to... The Cambria Daily Leader, 29 June 1914 The Carmarthen Journal and South Wales Weekly Adver@ser, 31 July, 1914 How did this incident create a world war? Countries formed partnerships or alliances with other countries to protect them if they were attacked. After Austria Hungary declared war on Serbia others joined in to defend their allies. Gavrilo Princip shoots the Arch- duke of Austria, Franz Ferdinand. Britain and Italy has an France have Austria- agreement with an Hungary Germany agreement defends Germany Russia and with Russia defends declares Austria- Hungary Austria- and join the Serbia war on Hungary war Serbia but refuses to join the war. Timeline - first months of War 28 June 1914 - Gavrilo Princip shoots 28 June, 1914 the Archduke of Austria, Franz Ferdiand and his wife in Sarajevo 28 July 1914 - Austria-Hungary declares war against Serbia. 28 July 1914 - Russia prepares for war against Austria-Hungary to protect Serbia. 4 August, 1914 1 August 1914 - Germany declares war against Russia to support Austria- Hungary. 3 August 1914 - Germany and France declare war against each other. 4 August 1914 - Germany attacks France through Belgium. Britain declares war against Germany to defend Belgium. War Begins - The Schlieffen Plan The Germans had been preparing for war for years and had devised a plan known as the ‘Schlieffen Plan’ to attack France and Russia. -

Europea NEO Brussels BRUSSELS

Europea NEO Brussels BRUSSELS Working with masterplanners KCAP and architects Jean-Paul Viguier, Gustafson Porter’s work at Europea Neo Brussels (‘Europea’) will create high-quality landscape within a new 68-hectare high-end mixed-use district surrounding the Roi Baudoin stadium. Our landscape design ensures this new district integrates into the surrounding urban fabric of Brussels and is chiefly comprised of the areas around the Mall of Europe, Europea gardens and the Euroville Park, home of the iconic Atomium. The design consists of large public spaces and a series of water features which offer rest areas, promenades and playgrounds for children. Our work on the Atomium Esplanade will create a spectacular space where waterfalls complement large lawns, offering a new perspective on the Atomium and the wider Heysel plateau. Won in international competition in 2012 the development was led by Jean-Paul Viguier Associés (France), with Gustafson Porter as landscape architect. The project has been developed by Unibail-Rodamco SE, BESIX and CFE, and encompasses 500 residential units, a 3.5ha park and 112.000m² dedicated to leisure, restaurants, an art district and the retail precinct “Mall of Europe”, a 72000m2 shopping centre which includes 9000m2 of restaurant and leisure facilities. It is estimated to receive 12-15 million visitors a year and is envisaged as a ‘smart city’ with high standards of environmental design. Full completion is expected at the end of 2021. “Development of the city must be organised to enable it to meet the great demo- graphic, economic and social challenges of the next ten years, and to position itself firmly as a cosmopolitan metropolis and capital of Europe. -

Chesterfield Wfa

CHESTERFIELD WFA Newsletter and Magazine issue 28 Patron –Sir Hew Strachan FRSE FRHistS President - Professor Peter Simkins MBE Welcome to Issue 28 - the April 2018 FRHistS Newsletter and Magazine of Chesterfield WFA. Vice-Presidents Andre Colliot Professor John Bourne BA PhD FRHistS The Burgomaster of Ypres The Mayor of Albert Lt-Col Graham Parker OBE Professor Gary Sheffield BA MA PhD FRHistS Christopher Pugsley FRHistS Lord Richard Dannat GCB CBE MC rd DL Our next meeting will be on Tuesday April 3 where our guest speaker will be the Peter Hart, no stranger to Roger Lee PhD jssc the Branch making his annual pilgrimage back to his old www.westernfrontassociation.com home town. Branch contacts Peter`s topic will be` Not Again` - the German Tony Bolton offensive on the Aisne, May 1918. ` (Chairman) anthony.bolton3@btinternet .com Mark Macartney The Branch meets at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, (Deputy Chairman) Chesterfield S40 1NF on the first Tuesday of each month. There [email protected] is plenty of parking available on site and in the adjacent road. Access to the car park is in Tennyson Road, however, which is Jane Lovatt (Treasurer) one way and cannot be accessed directly from Saltergate. Grant Cullen (Secretary) [email protected] Grant Cullen – Branch Secretary Facebook http://www.facebook.com/g roups/157662657604082/ http://www.wfachesterfield.com/ Western Front Association Chesterfield Branch – Meetings 2018 Meetings start at 7.30pm and take place at the Labour Club, Unity House, Saltergate, Chesterfield S40 1NF January 9th Jan.9th Branch AGM followed by a talk by Tony Bolton (Branch Chairman) on the key events of the last year of the war 1918.