Etcheson Layout

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A History of the Hort Department at KSU COVER.Pub

A History of the Horticulture Department at Kansas State University 18702012 Dr. Chuck Marr Professor (Emeritus) of Horticulture Kansas State University Horticulture Hall and Greenhouses Taken North from Anderson Hall roof Do you know? What was Anderson Hall called before it was renamed for President Anderson? What building is named for the 1st Professor of Horticulture at KSU? What feature in Manhattan City Park was created by a KSU Horticulturist? What 2 buildings on the campus today are named after KSU Horticulturists? What Head of the Horticulture Department did not have a college degree? How many ‘name changes’ has the Department gone through in its history? What 2 important ‘Firsts in the US’ was KSU Horticulture involved with? History of the Horticulture Department at Kansas State University Dr. Chuck Marr, Professor (Emeritus) of Horticulture Kansas State University An Introduction, Apology, Appreciation, and Dedication by the author: In anticipation of the 150th anniversary of Kansas State University, Dr. Stuart Warren asked that I compile a history of the Horticulture Department at Kansas State. I apologize for not approaching this with experience as an historian. I have attempted to draw accounts from sources listed at the end of this document and some of the accounts are from my own 40+ years association with the Department. I also appreciate the assistance of the K- State Archives and library staff for their assistance and patience. Beginning in the 1950s until now, there have been numerous faculty and staff assigned to the Department that are not mentioned but have dedicated themselves to the growth and success of Horticulture in Kansas. -

MAN of DOUGLAS, MAN of LINCOLN: the POLITICAL ODYSSEY of JAMES HENRY LANE Ian Michael Spurgeon University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2007 MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE Ian Michael Spurgeon University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Spurgeon, Ian Michael, "MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE" (2007). Dissertations. 1293. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1293 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE by Ian Michael Spurgeon A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. COPYRIGHT BY IAN MICHAEL SPURGEON 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The University of Southern Mississippi MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE by Ian Michael Spurgeon Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

Andrew Mccabe Fired for Cause Free

City, RCPD, District 383 Payrolls are on pages 4, 5........ part 4 Free Take One 31 VOLUME 26, NUMBER 46 Thursday, April 19, 2018 Bringing you the News in Print, Facebook and in 3D on the internet. Inspector General Report: Andrew McCabe Fired For Cause WASHINGTON (AP) — Andrew tacks on McCabe, a longtime target of congressional hearing soon after his McCabe, the fired FBI deputy director, the president’s ire, especially because firing. He could be an important wit- misled investigators and his own boss of revelations that his wife, during a ness for Mueller, who is investigating about his role in a news media disclo- failed state Senate run, had accepted Trump for possible obstruction of jus- sure about Hillary Clinton just days campaign contributions in 2015 from tice, including his motivation for firing before the 2016 presidential election the political action committee of then- Comey last May. and authorized the release of informa- Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a close Yet the report makes clear that the tion to “advance his personal inter- Clinton ally. McCabe and Comey were at odds over ests,” according to a Justice The president has made a concerted, how the conversations with the re- Department watchdog report. Twitter-driven effort to impugn Mc- porter unfolded and exactly how it had President Donald Trump, already Cabe as a partisan hack, accusing him been approved. furious over a forthcoming book from of covering up unspecified “lies and fired FBI Director James Comey, corruption” at the FBI and calling his McCabe told the -

Upk Olson.Indd

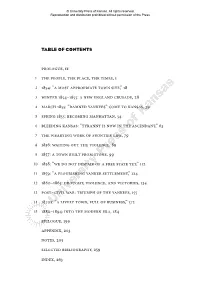

© University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. table oF ContentS prologue, ix 1 the people, the place, the times, 1 2 1854: “a most appropriate town site,” 18 3 winter 1854–1855: a new england crusade, 28 4 march 1855: “damned yankees” come to kansas, 39 5 spring 1855: becoming manhattan, 54 6 bleeding kansas: “tyranny is now in the ascendant,” 63 7 the wearying work of frontier life, 79 8 1856: waiting out the violence, 89 9 1857: a town built from stone, 99 10 1858: “we do not despair of a free state yet,” 112 11 1859: “a flourishing yankee settlement,” 124 12 1860–1865: drought, violence, and victories, 134 13 post–civil war: triumph of the yankees, 155 14 1870s: “a lively town, full of business,” 172 15 1880–1894: into the modern era, 184 epilogue, 199 appendix, 203 notes, 205 selected bibliography, 259 index, 263 © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. ProloGUe On a frosty afternoon in Kansas Territory on March 27, 1855, a stern Rhode Island abolitionist named Isaac Goodnow and five other New Englanders wrestled a bulky canvas tent into shape in a tallgrass prairie at the junction of the Kansas and Big Blue rivers. The prairie was colder than Goodnow had imagined it would be in late March. But he and his party were in good spirits as they moved mattresses and supplies from the wagon into their campsite: the men had finally reached their destination after a three-week trip from Boston, covering 1,500 miles, capped by a struggle to get their overburdened covered wagon through the snowstorms and icy riv- ers of Kansas Territory. -

An Ethnographic Study of the Kansas Historical Society's

FACE, SPACE, AND ANXIETY: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE KANSAS HISTORICAL SOCIETY’S SOCIAL MEDIA USAGE by SJOBOR HAMMER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Cognitive Linguistics CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis of Sjobor Hammer candidate for the degree of Master of Arts *. Committee Chair Todd Oakley Committee Member William Deal Committee Member Mark Turner Date of Defense March 17, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. To Mom, Dad, and Nathan TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................................. 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE KANSAS HISTORICAL SOCIETY .................................. 14 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................... 19 ANALYSIS .................................................................................................................................. -

Late 19Th Century and Early 20Th Century Residential Resources in Manhattan, Kansas

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section E Page 1 Late Nineteenth Century and Early Twentieth Century Residential Resources in Manhattan, Kansas Riley County, Kansas DEVELOPMENT OF MANHATTAN, KANSAS: 1855-1945 Manhattan, Kansas is located in the north-central region of the state and is the county seat of Riley County. It is located in a bowl-shaped valley immediately north of the Kansas River near its confluence with the Big Blue River. Riley County received its name directly from the military post named after General Benjamin Riley1 located approximately twelve miles southwest of Manhattan’s original settlement area. FIGURE 1: MANHATTAN, KANSAS LOCATION MAP Map Courtesy of World Sites Atlas N 1 In July 1852, Colonel T. T. Fauntleroy of the First Dragoons recommended the establishment of a military post near a point on the Kansas River where it merged with the Republican Fork River. In May 1853, a commission elected the present site of Fort Riley and construction began soon thereafter. On July 26, 1858, the U.S. Army formally designated the military installation as Fort Riley. NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section E Page 2 Late Nineteenth Century and Early Twentieth Century Residential Resources in Manhattan, Kansas Riley County, Kansas TERRITORIAL PERIOD (1850-1861) Founded between 1854 and 1855 by three groups of Anglo-American settlers from New England and Ohio who jointly platted the town, the community of Manhattan is in Riley County, the westernmost county organized by the Kansas Territorial Legislature of 1855. -

11/16/06 Riley County History Annotated Bibliography

11/16/06 RILEY COUNTY HISTORY ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY Compiled by Virginia Quiring, Riley County Historical Museum With suggestions from Riley County Historical Museum Staff and the C150! Heritage Committee. The following bibliography is intended to provide an overview of published works on the history of Riley County held in local libraries and museums. It covers Riley County history to the present—biographies and autobiographies of citizens, history of local institutions, and other works that relate significantly to the history of Riley County. Location of current (2005-2006) holdings at local libraries and museums indicated by the following key: RCHM - Riley County Historical Museum RCGS – Riley County Genealogical Society MPL – Manhattan Public Library Hale – Hale Library, Kansas State University An asterisk (*) after the key indicates the publication is for sale at that location. Some of the holdings at the Manhattan Public Library and Hale Library at Kansas State University may be available through interlibrary loan. The Riley County Historical Museum library and archives is a non-circulating research collection. The Riley County Genealogical Society collection has a limited circulation. Links to the websites of these institutions can be found on the Historical Research page of the Riley County website: http://www.rileycountyks.gov/museum/ BOOKS: Ambrose, Stephen E. Milton S. Eisenhower, Educational Statesman. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983. Traces Eisenhower’s path from small town Kansas to Washington bureaucracy and through presidencies of Kansas State University, Pennsylvania State U., and Johns Hopkins University. MPL; Hale Lib Ambrose, Stephen E. Nothing Like It in the World; the men who built the Transcontinental Railroad, 1863-1869. -

Chapter 1 Introduction

Chapter 1 Introduction “Bleeding Kansas” is the popular phrase had to adapt to the environment they found. describing the conflict over slavery in What happened as successive waves of set- Kansas that became nationally prominent tlers tried to remove others and as different just before and during the American Civil groups tried to change the beliefs of others War. Pro-slavery settlers from the South and caused the Kansas Conflict. The struggle anti-slavery activists from the north came to during the territorial period set the stage for the territory because it was located at the continued struggles, even today. In this intersection of Northern and Southern expan- adaptation, Kansas is a microcosm of our sion. Because of the Kansas conflict over nation, holding examples of many struggles whether the territory would become a free for freedom within its boundaries. state or not, Kansans first acted out the vio- lence that would engage all Americans Today, many places in the eastern Kansas beginning in 1861. Born in that early con- landscape look much as they did in the terri- flict, Kansas became the strategic center of torial period when Native Americans, an emerging continental nation. In the European Americans, and African Americans Kansas Conflict, American settlers first struggled to adapt to the treeless landscape fought to uphold their different and irrecon- and the harshly variable climate of the Great cilable principles of freedom and equality. Plains. Although these settlers recreated a The place where this crucial step toward the landscape of farms and towns like that of the outbreak of the Civil War occurred has not eastern United States, Kansas is still a fron- yet received the recognition accorded to tier where people struggle to make a living other Civil War landscapes. -

Cultures of Dissent: Comparing Populism in Kansas and Texas

CULTURES OF DISSENT: COMPARING POPULISM IN KANSAS AND TEXAS, 1854-1890 A Dissertation by MATTHEW JERRID KEYWORTH Submitted to the Office of Graduate and Professional Studies of Texas A&M University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Chair of Committee, David Vaught Committee Members, Carlos Blanton Charles Brooks Sarah Gatson Head of Department, David Vaught May 2014 Major Subject: History Copyright 2014 Matthew J. Keyworth ABSTRACT In 1892, People’s Party candidate James Weaver won more than a million votes and four states in his bid for the presidency. Despite finishing third, the fledgling party’s promising start worried Democrats and Republicans alike. Although Populists demonstrated strength across the South and in the West, Kansas and Texas stood at the movement’s center. Populism grew outward from areas first settled by whites in the 1850s. Farmers in both states initially struggled with new climates, crops, and soils, and they turned to neighbors for help in facing challenges great and small. The culture of mutual aid that developed enabled survival while forging a sense of community—and responsibility for the common weal—that endured through century’s end. In addition to impediments erected by Mother Nature, early homesteaders faced the obstacle of settling in contested places. Anxieties surrounding Bleeding Kansas ensnared even those who cared little about slavery, just as fear of “Indian depredations” consumed Texans. In both circumstances many believed that federal authorities at best ignored—and at worst added to—their problems. Kansans and Texans walked divergent paths following the Civil War. -

The Great Principle of Self-Government

The Great Principle of Self-Government Popular Sovereignty and Bleeding Kansas by Nicole Etcheson Now, my friends, if we will only act conscientiously and rigidly upon this great principle of pop- ular sovereignty, which guaranties to each State and Territory the right to do as it pleases on all things, local and domestic, instead of Congress interfering, we will continue at peace one with an- other. Under that principle we have become, from a feeble nation, the most powerful on the face of the earth, and if we only adhere to that principle, we can go forward increasing in territory, in power, in strength and in glory until the Republic of America shall be the North Star that shall guide the friends of freedom throughout the civilized world. And why can we not adhere to the great principle of self-government, upon which our institutions were originally based? —Senator Stephen A. Douglas, 1858.1 ngaged in a struggle to salvage his political career, Stephen A. Douglas spoke these words to his constituents in Ottawa, Illinois, during his famous debates with Abraham Lincoln. In Douglas’s view, popular sovereignty was nothing less than the “great prin- ciple of self-government” itself. He had equated the two before and would do so again. EPopular sovereignty, as one historian has pointed out, “rested on a historic, enduring, and deeply held belief in the capacity of the American people not only to govern themselves but to do what Nicole Etcheson is an associate professor of history at the University of Texas–El Paso. Her research has examined Bleeding Kansas, the various factions of the antislavery and proslavery movements, and the subject of popular sovereignty. -

Aggieville Historic Resources Inventory Survey Report

KANSAS HISTORIC RESOURCES INVENTORY SURVEY REPORT Aggieville Commercial District Historic Survey May 2020 K-State parade in Aggieville, 1939 Royal Purple Brenda R. Spencer Prepared for the Michelle Spencer 10150 Onaga Road City of Manhattan Wamego, KS 66547 May 2020 [email protected] The survey report and inventory forms, which are the subject of this project, have been financed in part with federal funds from the National Park Service, a division of the United States Department of the Interior, and administered by the Kansas State Historical Society. The City of Manhattan received a Historic Preservation Fund Grant through the Kansas State Historical Society for the project. Aggieville Commercial District HISTORIC SURVEY REPORT MAY 2020 I. OVERVIEW Brenda R. Spencer 10150 Onaga Road The Aggieville Community Vision was adopted in the spring of 2017. Lead by the Wamego, KS 66547 Brenda@SpencerPreservation public input of over 4,200 participants, stakeholders, and Manhattan citizens, it identifies several redevelopment and public improvement opportunities in the district. The plan included a recommendation to preserve the historic character of Aggieville’s historic core and this survey project resulted in part from that commitment. The plan's implementation is now underway including construction of a hotel and planning for a parking garage. The City of Manhattan was awarded a Historic Preservation Fund Grant by the Kansas State Historical Society in May 2019. Spencer Preservation was hired by the Historic Preservation Fund Grant City of Manhattan through a competitive bid process in November 2019 to conduct a 2019-05 historic resource survey of the Aggieville Commercial District. -

K-State Keepsakes

Kansas State University Libraries New Prairie Press NPP eBooks Monographs 1-28-2015 K-State Keepsakes Anthony R. Crawford Kansas State University Follow this and additional works at: https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks Part of the American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Digital Humanities Commons, and the Higher Education Commons Recommended Citation Crawford, Anthony R., "K-State Keepsakes" (2015). NPP eBooks. 3. https://newprairiepress.org/ebooks/3 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Monographs at New Prairie Press. It has been accepted for inclusion in NPP eBooks by an authorized administrator of New Prairie Press. For more information, please contact [email protected]. K-State Keepsakes Anthony R. Crawford Copyright © 2015 Anthony R. Crawford New Prairie Press Kansas State University Libraries Manhattan, Kansas Cover design by: Kansas State University Libraries Electronic edition available online at: http://newprairiepress.org/monographs/ This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ ISBN: 0991548221 ISBN-13: 978-0-9915482-2-4 Contents Introduction ................................................................................................................................................... i Julia R. Pearce, K-State’s First Librarian ........................................................................................................ 1 Basketball Madness .....................................................................................................................................