A History of the Hort Department at KSU COVER.Pub

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving

1 Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving Tour July 2020 This self-guided driving tour was developed by the staff of the Riley County Historical Museum to showcase some of the interesting and important African American history in our community. You may start the tour at the Riley County Historical Museum, or at any point along to tour. Please note that most sites on the driving tour are private property. Sites open to the public are marked with *. If you have comments or corrections, please contact the Riley County Historical Museum, 2309 Claflin Road, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 785-565-6490. For additional information on African Americans in Riley County and Manhattan see “140 Years of Soul: A History of African-Americans in Manhattan Kansas 1865- 2005” by Geraldine Baker Walton and “The Exodusters of 1879 and Other Black Pioneers of Riley County, Kansas” by Marcia Schuley and Margaret Parker. 1. 2309 Claflin Road *Riley County Historical Museum and the Hartford House, open Tuesday through Friday 8:30 to 5:00 and Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00. Admission is free. The Museum features changing exhibits on the history of Riley County and a research archive/library open by appointment. The Hartford House, one of the pre-fabricated houses brought on the steamboat Hartford in 1855, is beside the Riley County Historical Museum. 2. 2301 Claflin Road *Goodnow House State Historic Site, beside the Riley County Historical Museum, is open Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00 and when the Riley County Historical Museum is open and staff is available. -

The Name and Family of Fairchild

REVISED EDITION OF THE NAME AND FAMILY OF FAIRCHILD tA «/-- .COMPILED BY TM.'FAIRCHILD, LL.B. OP ' IOWA CITY, IOWA ASSISTED BY SARAH ELLEN (FAIRCHILD) FILTER, WIPE OP FIRST LIEUTENANT CHESTER FILTER OP THE ARMY OP THE U. S. A. DUBUQUE, IOWA mz I * r • • * • • » < • • PUBLISHED BY THE MERCER PRINTING COMPANY IOWA CITY, IOWA 1944 201894 INDEX PART ONE Page Chapter I—The Name of Fairchild Was Derived From the Scotch Name of Fairbairn 5 Chapter II—Miscellaneous Information Regarding Mem bers of the Fairchild Family 10 Chapter III—The Heads of Families in the United States by the Name of Fairchild as Recorded by the First Census of the United States in 1790 50 Chapter IV—'Copy of the Fairchild Manuscript of the Media Research Bureau of Washington .... 54 Chapter V—Copy of the Orcutt Genealogy of the Ameri can Fairchilds for the First Four Generations After the Founding of Stratford and Settlement There in 1639 . 57 Chapter VI—The Second Generation of the American Fairchilds After Founding Stratford, Connecticut . 67 Chapter VII—The Third Generation of the American Fairchilds 71 Chapter VIII—The Fourth Generation of the American Fairchilds • 79 Chapter IX—The Extended Line of Samuel Fairchild, 3rd, and Mary (Curtiss) Fairchild, and the Fairchild Garden in Connecticut 86 Chapter X—The Lines of Descent of David Sturges Fair- child of Clinton, Iowa, and of Eli Wheeler Fairchild of Monticello, New York 95 Chapter XI—The Descendants of Moses Fairchild and Susanna (Bosworth) Fairchild, Early Settlers in the Berkshire Hills in Western Massachusetts, -

A Self Guided Driving Tour of Manhattan, Kansas Developed by the Riley County Historical Society and Museum November 2018

1 “Where the Adventure Began: Touring the Home Town of the Food Explorers” A self guided driving tour of Manhattan, Kansas Developed by the Riley County Historical Society and Museum November 2018 (This is a work in progress. If you have corrections or suggestions, please contact the Riley County Historical Museum.) This self-guided driving tour was developed for the 2018 Kansas State University K-State Science Communication Week activities to coordinate with the events sponsored by the Kansas State University Global Food Systems Initiative around the book “The Food Explorer: The True Adventures of the Globe-Trotting Botanist Who Transformed What America Eats” by Daniel Stone. The tour primarily focuses on the Manhattan places between 1864, when the Marlatt family returned to Manhattan from a short stay in the Kansas City area, and 1897, when the Fairchild family left Manhattan. That period in Manhattan would been part of the lives of David Fairchild, the “Globe-Trotting Botanist Who Transformed What America Eats” and two of his childhood friends and colleagues, Charles L. Marlatt, and Walter T. Swingle. In 1880 Manhattan had a population of 2,105 and Kansas State Agricultural College had an enrollment of 267. In 1890 Manhattan had a population of 3,004 and Kansas State Agricultural College had an enrollment of 593. David G. Fairchild (1869 – 1954) was the son of Kansas State Agricultural College President George T. Fairchild and Charlotte Halsted Fairchild. His family came to Manhattan in 1879, when his father took the job as KSAC President. David graduated from KSAC in 1888 and began a long, adventurous, and productive career as a “food explorer” for the Office of Seed and Plant Introduction of the U.S. -

MAN of DOUGLAS, MAN of LINCOLN: the POLITICAL ODYSSEY of JAMES HENRY LANE Ian Michael Spurgeon University of Southern Mississippi

The University of Southern Mississippi The Aquila Digital Community Dissertations Summer 8-2007 MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE Ian Michael Spurgeon University of Southern Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations Part of the Military History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Spurgeon, Ian Michael, "MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE" (2007). Dissertations. 1293. https://aquila.usm.edu/dissertations/1293 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The University of Southern Mississippi MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE by Ian Michael Spurgeon A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Approved: August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. COPYRIGHT BY IAN MICHAEL SPURGEON 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. The University of Southern Mississippi MAN OF DOUGLAS, MAN OF LINCOLN: THE POLITICAL ODYSSEY OF JAMES HENRY LANE by Ian Michael Spurgeon Abstract of a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Studies Office of The University of Southern Mississippi in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. -

The FBI Relied on the Unverified Steele Dossier

Free Take One 31 VOLUME 27, NUMBER 8 Thursday, July 26, 2018 Our Twenty Seventh Year of Bring Manhattan Local, State, And National News FISA Applications Confirm: The FBI Relied on the Unverified Steele Dossier A salacious Clinton- represented that it had “re- corroborating the dossier alle- stead, they used the dossier be- campaign product was viewed this verified application gations against Mr. Page. cause, as McCabe told the for accuracy.” But did the bu- The senators went on to re- House Intelligence Committee, the driving force be- reau truly ensure that the infor- count the concession by former without it they would have had hind the Trump–Rus- mation had been “thoroughly FBI director James Comey that no chance of persuading a judge sia investigation. vetted and confirmed”? Re- the bureau had relied on the that Page was a clandestine member, we are talking here credibility of Steele (who had agent. By Andrew C. McCarthy about serious, traitorous allega- previously assisted the bureau Whatever is in the redactions National Review tions against an American citi- in another investigation), not cannot change that. On a sleepy summer Satur- zen and, derivatively, an the verification of Steele’s There Is No Vicarious Credi- day, after months of American presidential cam- sources. In June 2017 testi- bility stonewalling, the FBI dumped paign. mony, Comey described infor- To repeat what we’ve long 412 pages of documents related When the FBI averred that it mation in the Steele dossier as said here, there is no vicarious to the Carter Page FISA surveil- had verified for accuracy the “salacious and unverified.” credibility in investigations. -

Andrew Mccabe Fired for Cause Free

City, RCPD, District 383 Payrolls are on pages 4, 5........ part 4 Free Take One 31 VOLUME 26, NUMBER 46 Thursday, April 19, 2018 Bringing you the News in Print, Facebook and in 3D on the internet. Inspector General Report: Andrew McCabe Fired For Cause WASHINGTON (AP) — Andrew tacks on McCabe, a longtime target of congressional hearing soon after his McCabe, the fired FBI deputy director, the president’s ire, especially because firing. He could be an important wit- misled investigators and his own boss of revelations that his wife, during a ness for Mueller, who is investigating about his role in a news media disclo- failed state Senate run, had accepted Trump for possible obstruction of jus- sure about Hillary Clinton just days campaign contributions in 2015 from tice, including his motivation for firing before the 2016 presidential election the political action committee of then- Comey last May. and authorized the release of informa- Virginia Gov. Terry McAuliffe, a close Yet the report makes clear that the tion to “advance his personal inter- Clinton ally. McCabe and Comey were at odds over ests,” according to a Justice The president has made a concerted, how the conversations with the re- Department watchdog report. Twitter-driven effort to impugn Mc- porter unfolded and exactly how it had President Donald Trump, already Cabe as a partisan hack, accusing him been approved. furious over a forthcoming book from of covering up unspecified “lies and fired FBI Director James Comey, corruption” at the FBI and calling his McCabe told the -

Upk Olson.Indd

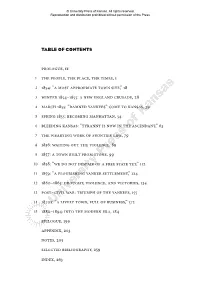

© University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. table oF ContentS prologue, ix 1 the people, the place, the times, 1 2 1854: “a most appropriate town site,” 18 3 winter 1854–1855: a new england crusade, 28 4 march 1855: “damned yankees” come to kansas, 39 5 spring 1855: becoming manhattan, 54 6 bleeding kansas: “tyranny is now in the ascendant,” 63 7 the wearying work of frontier life, 79 8 1856: waiting out the violence, 89 9 1857: a town built from stone, 99 10 1858: “we do not despair of a free state yet,” 112 11 1859: “a flourishing yankee settlement,” 124 12 1860–1865: drought, violence, and victories, 134 13 post–civil war: triumph of the yankees, 155 14 1870s: “a lively town, full of business,” 172 15 1880–1894: into the modern era, 184 epilogue, 199 appendix, 203 notes, 205 selected bibliography, 259 index, 263 © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. © University Press of Kansas. All rights reserved. Reproduction and distribution prohibited without permission of the Press. ProloGUe On a frosty afternoon in Kansas Territory on March 27, 1855, a stern Rhode Island abolitionist named Isaac Goodnow and five other New Englanders wrestled a bulky canvas tent into shape in a tallgrass prairie at the junction of the Kansas and Big Blue rivers. The prairie was colder than Goodnow had imagined it would be in late March. But he and his party were in good spirits as they moved mattresses and supplies from the wagon into their campsite: the men had finally reached their destination after a three-week trip from Boston, covering 1,500 miles, capped by a struggle to get their overburdened covered wagon through the snowstorms and icy riv- ers of Kansas Territory. -

An Ethnographic Study of the Kansas Historical Society's

FACE, SPACE, AND ANXIETY: AN ETHNOGRAPHIC STUDY OF THE KANSAS HISTORICAL SOCIETY’S SOCIAL MEDIA USAGE by SJOBOR HAMMER Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Cognitive Linguistics CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis of Sjobor Hammer candidate for the degree of Master of Arts *. Committee Chair Todd Oakley Committee Member William Deal Committee Member Mark Turner Date of Defense March 17, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. To Mom, Dad, and Nathan TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES ......................................................................................................................... 5 ABSTRACT .................................................................................................................................... 7 INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1 LITERATURE REVIEW ............................................................................................................. 1 AN INTRODUCTION TO THE KANSAS HISTORICAL SOCIETY .................................. 14 METHODOLOGY ...................................................................................................................... 19 ANALYSIS .................................................................................................................................. -

Etcheson Layout

“Labouring for the Freedom of This Territory” Free-State Kansas Women in the 1850s by Nicole Etcheson n 1855 Harriet Goodnow refused her husband William’s pleas to join him in Kansas. The Goodnow brothers, Isaac and William, had arrived in March and settled along Wild Cat Creek, having chosen a site on the outskirts of what is now Manhattan, Kansas. IIsaac, who had been an educator in Rhode Island, became one of the founders of Manhattan and later of what would become Kansas State University. In the manner common in settling the frontier, Isaac and William came on ahead of their wives to establish a claim, build a cabin, and put in the first year’s crop. Within four months, Isaac’s wife, Ellen, followed him to Kansas. William’s wife, Harriet, refused to come to Kansas, and instead remained in New England. The tale of the Goodnow women, and that of other eastern women who moved to Kansas, relates the un- usual interplay of politics, domesticity, and western settlement in the lives of nineteenth-century women. As did many of the New Englanders who migrated to Kansas in the 1850s, the Goodnows responded to the call to save Kansas for freedom. The Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 had repealed the prohibition against slavery in the northern part of the Louisiana Purchase out of which Kansas Territory was formed. Kansas thus had its origins in the national struggle over slavery extension. The New England settlements there experienced first threats and then civil war with Missourians resentful of free-state intrusion onto their borders. -

A Historical Look at the Development of 17Th Street

A HISTORICAL LOOK AT THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE 17TH STREET CORRIDOR THROUGH THE KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY CAMPUS by TOMOYA SUZUKI A REPORT submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree MASTER OF REGIONAL AND COMMUNITY PLANNING Department of Landscape Architecture/Regional and Community Planning College of Architecture, Planning and Design KANSAS STATE UNIVERSITY Manhattan, Kansas 2010 Approved by: Major Professor Ray Weisenburger Copyright TOMOYA SUZUKI 2010 Abstract This report examines how 17th Street on the Kansas State University campus, initially a service road on the west edge of the campus, has become a major point of public campus access while retaining its function as a service road. In addition, this report conducts interviews with 10 persons with various backgrounds and experiences involving 17th Street to understand public impressions and interests regarding 17th Street. Finally, this report reviews future development scenarios of 17th Street that allow 17th Street to be a contributor with a distinctive character to the university. When Kansas State University was transferred from old Bluemont Central College to its current location in 1875, 17th Street, which now crosses the middle of the campus on a North-South axis, was outside of the campus’ core facility areas. As various university programs have grown throughout the late 20th Century, the campus of Kansas State University has expanded toward the west. As a result, the relative proximity of 17th Street to the center of campus has changed. Now, 17th Street is recognized as one of the major entrances to campus from the south; yet because of the street’s initial and ongoing service function and its service- related facilities, there are parts of the corridor that are not attractive. -

Late 19Th Century and Early 20Th Century Residential Resources in Manhattan, Kansas

NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section E Page 1 Late Nineteenth Century and Early Twentieth Century Residential Resources in Manhattan, Kansas Riley County, Kansas DEVELOPMENT OF MANHATTAN, KANSAS: 1855-1945 Manhattan, Kansas is located in the north-central region of the state and is the county seat of Riley County. It is located in a bowl-shaped valley immediately north of the Kansas River near its confluence with the Big Blue River. Riley County received its name directly from the military post named after General Benjamin Riley1 located approximately twelve miles southwest of Manhattan’s original settlement area. FIGURE 1: MANHATTAN, KANSAS LOCATION MAP Map Courtesy of World Sites Atlas N 1 In July 1852, Colonel T. T. Fauntleroy of the First Dragoons recommended the establishment of a military post near a point on the Kansas River where it merged with the Republican Fork River. In May 1853, a commission elected the present site of Fort Riley and construction began soon thereafter. On July 26, 1858, the U.S. Army formally designated the military installation as Fort Riley. NPS Form 10-900-a OMB No. 1024-0018 (8-86) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section E Page 2 Late Nineteenth Century and Early Twentieth Century Residential Resources in Manhattan, Kansas Riley County, Kansas TERRITORIAL PERIOD (1850-1861) Founded between 1854 and 1855 by three groups of Anglo-American settlers from New England and Ohio who jointly platted the town, the community of Manhattan is in Riley County, the westernmost county organized by the Kansas Territorial Legislature of 1855. -

Enter Or Copy the Title of the Article Here

This is a student project that received either a grand prize or an honorable mention for the Kirmser Undergraduate Research Award. Education in the 'right' sense of the word: The quest for a balanced education at the Kansas State Agricultural College Colin T. Halpin Date Submitted: May 11, 2015 Kirmser Award Kirmser Undergraduate Research Award – Individual Non-Freshman category, grand prize How to cite this manuscript If you make reference to this paper, use the citation: Halpin, C. T. (2015). Education in the „right‟ sense of the word: The quest for a balanced education at the Kansas State Agricultural College. Retrieved from http://krex.ksu.edu Abstract & Keywords After the establishment of the Kansas State Agriculture College in accordance with the Morrill Act, there was significant disapproval for the scope of education at the school, in favor of a more “practical” agricultural education which came under the leadership of President Anderson. Although Anderson made significant efforts in advancing education, his moves were too radical, and the final direction of the college was determined when President George Fairchild successfully combined the practical and classical structures to provide a broad curriculum that did not ignore the importance of hands-on training, and in doing so, he built a model agricultural college for the nation. Keywords: Kansas State Agricultural College, President George Fairchild, Education, Reform Course Information School: Kansas State University Semester: Spring 2015 Course Title: Advanced Seminar in History Course Number: HIST 586 Instructor: Dr. Charles Sanders This item was retrieved from the K-State Research Exchange (K-REx), the institutional repository of Kansas State University.