K-State Keepsakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020-21 Schedule

KANSAS STATE MEN’S BASKETBALL 2020-21 SCHEDULE LITTLE APPLE CLASSIC The field includes Colorado, Drake and South Dakota State DAY DATE OPPONENT [2019-20 RECORD] LOCATION TIME / TV 2019-20 RESULT SERIES Wednesday Nov. 25 Colorado vs. South Dakota State Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] ——— Drake [20-14] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — — K-State leads 20-6 Friday Nov. 27 Drake vs. South Dakota State Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] ——— Colorado [21-11] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — — K-State leads 96-47 DAY DATE OPPONENT [2019-20 RECORD] LOCATION TIME / TV 2019-20 RESULT SERIES Monday Nov. 30 Kansas City [16-14] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — -- K-State leads 18-1 Saturday Dec. 5 UNLV [17-15] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — W, 60-56 (OT) UNLV leads 4-3 Tuesday Dec. 8 Milwaukee [12-19] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — -- First meeting BIG 12/BIG EAST BATTLE DAY DATE OPPONENT [2019-20 RECORD] LOCATION TIME / TV 2019-20 RESULT SERIES TBD BIG 12 CONFERENCE DAY DATE OPPONENT [2019-20 RECORD] LOCATION TIME / TV 2019-20 RESULT SERIES Tuesday Dec. 15 @Iowa State* [12-20] Ames, Iowa [Hilton Coliseum] — L, 63-73 K-State leads 141-90 Saturday Dec. 19 Baylor* [26-4] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — L, 67-73 K-State leads 23-20 DAY DATE OPPONENT [2019-20 RECORD] LOCATION TIME / TV 2019-20 RESULT SERIES Monday Dec. 21 Jacksonville [14-18] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — -- First meeting Tuesday Dec. 29 South Dakota [20-13] Manhattan [Bramlage Coliseum] — -- K-State leads 10-0 BIG 12 CONFERENCE DAY DATE OPPONENT [2019-20 RECORD] LOCATION TIME / TV 2019-20 RESULT SERIES Saturday Jan. -

University and Presidential Position Profile 2021 Executive Summary

UNIVERSITY AND PRESIDENTIAL POSITION PROFILE 2021 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Kansas State University (K-State) seeks an experienced, The incoming president should possess a demonstrated track accomplished and authentic leader with a strong commitment record of successful leadership with significant administrative to student access and success, and the mission of land-grant and leadership experience at an institution or organization institutions, to serve as its next president. of comparable size, scope and complexity. The president should be a person of high integrity and character with strong Kansas State University is a comprehensive, research, land- interpersonal, collaboration, diplomacy and communication grant institution serving students and the people of Kansas, the skills. A commitment to student access and success, teaching nation and the world. Since its founding in 1863, the university excellence and entrepreneurial research activity that has a lasting has evolved into a modern institution of higher education, impact on the state, nation and world will be important. The committed to quality programs, and responsive to a rapidly president should have the skill to manage a highly complex, changing world and the aspirations of an increasingly diverse multisite institution, posse a deep knowledge and understanding society. Research and other creative endeavors comprise an of a mission-focused, distinctive land-grant university, essential component of K-State’s mission. All faculty members demonstrate facility in managing a budget in excess of $914.3 contribute to the discovery and dissemination of new million and have the ability to oversee the opportunities and knowledge, applications and products. These efforts, supported complexities involved in hosting an NCAA Division I athletics by public and private resources, are conducted in an atmosphere program. -

1A:Layout 2.Qxd

Priceless Take One Vol. 20 Number 48 An Award Winning Weekly Newspaper Thursday, May 10, 2012 City Debt: $160 Million In Four Years NBAF Funding In Appropriations Bill Wednesday, the House Appropria- sion of the Congress and the Federal tions Subcommittee on Homeland Government. I am pleased that the Security released its version of the House Appropriations Committee has FY2013 Homeland Security once again recognized the dire need for Appropriations bill. The subcommit- NBAF in our efforts to fulfill this tee approved language includes $75 responsibility to the American people. million for the construction of the The Department of Homeland Nation Bio and Agro-Defense Facility Security, under both the Bush and (NBAF) in Manhattan, Kansas, and Obama administrations, and the House directs the Department of Homeland Appropriations Committee, under both Security to complete a funding plan for Democrat and Republican leadership, the completion of the NBAF. have made it quite clear, time and Congress has previously appropriated again, that our Country needs the $40 million in FY2011 for the con- NBAF and the best place for the NBAF struction of the Central Utility Plant at is Manhattan, Kansas. While I was the NBAF and the $50 million in disappointed that President Obama’s FY2012 for the construction of the budget included no funding for con- facility as a whole. All told, these funds struction of this facility of tremendous will bring the total House commitment significance to our national security, I to construction on NBAF to $165 mil- appreciate the diligent work of my col- lion. leagues on the Homeland Security Congresswoman Jenkins released Subcommittee to ensure funds for the the following statement after the NBAF are included in their appropria- Homeland Security Appropriations tions bill. -

Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving

1 Manhattan, Kansas African American History Trail Self-Guided Driving Tour July 2020 This self-guided driving tour was developed by the staff of the Riley County Historical Museum to showcase some of the interesting and important African American history in our community. You may start the tour at the Riley County Historical Museum, or at any point along to tour. Please note that most sites on the driving tour are private property. Sites open to the public are marked with *. If you have comments or corrections, please contact the Riley County Historical Museum, 2309 Claflin Road, Manhattan, Kansas 66502 785-565-6490. For additional information on African Americans in Riley County and Manhattan see “140 Years of Soul: A History of African-Americans in Manhattan Kansas 1865- 2005” by Geraldine Baker Walton and “The Exodusters of 1879 and Other Black Pioneers of Riley County, Kansas” by Marcia Schuley and Margaret Parker. 1. 2309 Claflin Road *Riley County Historical Museum and the Hartford House, open Tuesday through Friday 8:30 to 5:00 and Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00. Admission is free. The Museum features changing exhibits on the history of Riley County and a research archive/library open by appointment. The Hartford House, one of the pre-fabricated houses brought on the steamboat Hartford in 1855, is beside the Riley County Historical Museum. 2. 2301 Claflin Road *Goodnow House State Historic Site, beside the Riley County Historical Museum, is open Saturday and Sunday 2:00 to 5:00 and when the Riley County Historical Museum is open and staff is available. -

Wednesday Thursday Friday Tuesday Wednesday Monday

Atchison County Mail March 12, 2015 Page 7 Blue Jay Corner Testing for the year will begin Senior 2015 April 1. The elementary is us- ing a superhero theme - Smash ashlynn the Test! As testing dates near, be sure to get enough rest, eat daugherty a good breakfast, and come to Future Plans: Attend the College of Hair Design school prepared to show off what Favorite TV Show: “Friends” you know! This is the first year that all tests grades 3 Most Embarrassing Moment: “Freshman year when Jordyn pulled down my pants in and up will be taken on computers. class.“ Favorite Store: Victoria’s Secret Advice to Underclassmen: Remember that everyone has a story. Everyone has gone through something that has changed them. Favorite Food: Lasagna Where Were You Born: St. Joe Senior 2015 Favorite Genre of Music: Classic country dalton By Jackie Bradley The student Blue Jays of the Week - March 6 newspaper of Mrs. Farley - Tatum Vogler Mrs. Weber - Harlee Pritt jones AY Rock Port Favorite Food: Pizza corner Mrs. Hughes - Alley Sharpless Mr. Parsons - Cori Jennings Favorite Movie: “The Big Lebowski” J R-II Schools. Mrs. Yocum - Pooja Patel Mrs. Hance - Quentin Jackson Favorite Teacher: Mr. Shineman 600 S. Ne- Mrs. Bredensteiner - Skylar & Kinleigh Daugherty (1) Future Plans: To attend college and major braska Street in social science Stoner Mrs. Sierks - Jadyn Geib & Jack Rock Port, MO Mrs. Vette - Jakobie Hayes Meyerkorth (K); Ryder Herron Favorite high school memory: When LUE Noah Makings threw up in the back of the 64482 Mrs. Lawrence - Malachi Skillen & Noah McCoy (1); Jaylynn Layout: Dayle van on the way to a volleyball game. -

Explore MHK the K-Stater's Guide to Manhattan

2021-22 Explore MHK The K-Stater's Guide to Manhattan collegianmedia.com/kstate-parent-guide/ 1 Find us in the Berney Family Welcome Center! Majors and Careers Take EDCEP 120, a one-credit hour course for career exploration Access free career assessments and resources Meet with a peer career specialist....or ask about becoming one! Your Potential Activate Handshake to search for jobs and internships Attend the Part-time Opportunities Fair Enroll in Internship Readiness course for credit or a digital badge Your Story Get help writing a resume, cover letter or personal statement Participate in a mock interview Shop for free professional wardrobe items from the Career Closet With Employers and Opportunities Network with employers at career fairs and career meet-ups Use tech-ready rooms for video interviews Get support with salary negotiation and accepting an offer www.k-state.edu/careercenter Table of Contents 2 About This Guide 4 Parents & Family Program 8 On-Campus Activities 10 K-State Traditions 12 Homecoming 15 Coffee Spots 18 Restaurants 22 Selfie Stops 25 Art 28 Outdoors 31 Transportation 34 Campus Calendar 35 Map collegianmedia.com/kstate-parent-guide/ 1 About This Guide Explore MHK, The K-Stater's Guide to Manhattan is a collaboration between the Parents and Family Program and the students of Collegian Media Group. Our goal is to provide families with the information and messages that they care about most. The content is crafted by students to target K-State parents and their new Wildcat students. Please refer to the Parents and Family Program at k-state.edu /parentsandfamily and k-state.edu for updates about the university. -

Rich Youth Kidnaped Federal Men Believe

Pa CRB TW B i.T» BATORDAT. DECHB1BBR14,196S. A m A itt DAILY OnODLATION TBB WBATBCa Sbi$ii^8trir Fnntittg SrrUlh fsr Ihs MmOIi ■( Nsvsatbsr, 1888 PofM sst ol O. S. WoMfeor 8 « n i 5 , 7 8 3 BortforS 'WkS •t Uw Aadit O m A $ tonight, Tnooday Coir; One 5x 7 Foggy Larkin at Ctewilstifliia deoMod ehaage In temporntaM. LT.WooifCo. The Key To A Great MANCHESTER — A CITY OP VILLAGE CHARM TEACHER OF DANCING SI BisseU St. TeL 4496 CHARITY Annonnees a Change From VOL.l v ., NO. 65. AdmrtMng on Pnge lo.) ENLARGEMENT MANCHESTER. CONN., MONDAY, DECEMBER 16. 1985. (TWELVE PAGES) PRICE THREE CBNlb Tuesday to Saturday, at AGENT Christmas Present WnH BVEBT BOIX or m u Orange Hall IWVELOFEDAND A f \ ^ FOR CARD PARTY rSlNTED, ALL FOB .. 4 U C Beginning Saturday, And A Lot O f Care When A Firehouse Bums Down— That’s News! Dec. 21 bPPERS To Provide Xmas Baskets 3 CITIES IN RACE Elite Studio 9 to 10 A. M., Beginners; Free Motoring A RICH YOUTH KIDNAPED Boom • 988 Main SL, npateln 10 On, Advanced Pupils. fT . BRODGET'S FOR G. 0 . P. PARLEY 6 New FEDERAL MEN BELIEVE Cash PARISH HALL CleYeland, Chicago and Kan- Photographs Read The Herald Advs. Price JAPANESE TAKE Ton n s Citj Make Bids— Scion of One of Pbladel- Monday, Dec. 16, 8P. M. Cuban Soldiers Find $3 .0 0 dozen DODGE Fletcher Declares New GATEWAY POST phb’s First Families Db- Make your appointment now U DOOR PRIZE! PLAYING PRIZES I you wish srour pictures for Christ- PLACE YOUR ORDER NOW FOR XMAS DELIVERY! REFRESHMENTS t I N N O O CHINA Rich Kidnap Victim appears from New York TON IGH T .\dmission.............................................. -

Great Gift Ideas

May 2009, Volume 5, Issue 5, www.manhattan.org A publication of the Manhattan Area Chamber of Commerce Congratulations Graduates! On April 22 at the Manhattan Country c) how strongly you believe in your ability to When asked how she balances work and Club, the Leadership Manhattan Class of reach that goal. family, Suzie answered that having a strong 2009 Graduation took place, with over support system and her time management 100 people in attendance. Sue Maes, with Coach Suzie Fritz also shared an inspiring skills have been the keys. Another question K-State Division of Continuing Education, quote: “Confidence is derived from demon- she received was, “how do you motivate received the Distinguished Service Alumni strated ability.” She also told that to be a Continued on page 10 Award. The Leadership Manhattan Scholar- leader you must: ship Award recipient was Rock Creek senior, a) manage conflict (the Contact us: Tyler Umscheid. Tyler plans to attend ability to influence and 501 Poyntz Avenue Kansas State University this fall and major motivate helps) Manhattan, KS, 66502-6005 in Mechanical Engineering. b) have knowledge 785-776-8829 phone (who you know gets 785-776-0679 fax K-State Head Volleyball Coach Suzie Fritz you there, who you are [email protected] was the featured speaker. She shared that keeps you there) www.manhattan.org leadership is “the ability to motivate to a c) have good character TDD Kansas Relay Center: common goal.” Suzie said you have to mold (must be fair, have 800-766-3777 people, develop them, and show them what genuine care and con- to do. -

Kansas State Facilities Use 09-10

D34 / STUDENT LIFE HANDBOOK tions and what the complainant and respondent must to do to file an appeal or a may be asked by KSU Police to provide personal identification, so that Kansas grievance. If the team determines that the respondent violated this Policy, it will State University may determine persons with knowledge of, or responsibility for, prepare a written report to the complainant, the respondent and the responsible campus damage or injury. Persons without personal identification may not play administrator that describes the review, presents findings and recommendations disc golf until they have suitable identification. for sanctions and remedial actions, referrals and follow-up and explains what the Persons in violation of this policy may be subject to sanctions, including but not complainant and respondent must to do to file an appeal or a grievance. limited to, removal from campus, being banned from campus, or being charged I. Appeals Beyond the Administrative Review Process : A complainant or with criminal trespass. respondent who is not satisfied with the resolution of a complaint, may appeal the .030 Questions administrative review team’s determination and/or, any sanction(s) imposed by Questions regarding this policy are to be directed to the KSU Vice President for the responsible administrator. Administration and Finance at (785) 532-6226. 1. A classified employee with permanent status may appeal to the Classified Employee Peer Review Committee. DIVISION OF FACILITIES 2. A current and former unclassified professional and faculty may appeal to the General Grievance Board. Facility Use Guidelines 3. An undergraduate student may appeal to the Student Discrimination Review A benefit of being a registered organization is the opportunity to use University Committee. -

Contents Chapter 3 Risk Assessment

Contents Chapter 3 Risk Assessment ................................................................................................................ 3 3.1 Exposure and Analysis of State Development Trends ................................................................. 5 3.1.1. Growth ..................................................................................................................................... 5 3.1.2. Population ................................................................................................................................ 5 3.1.3 Social Vulnerability................................................................................................................ 24 3.1.4. Land Use and Development Trends .................................................................................... 27 3.1.5. Exposure of Built Environment/Cultural Resources ......................................................... 35 3.2. Hazard Identification ................................................................................................................... 48 3.2a. Potential Climate Change Impacts on the 22 Identified Hazards in Kansas ........................ 63 3.3. Hazard Profiles and State Risk Assessment .............................................................................. 65 3.3.1. Agricultural Infestation ........................................................................................................ 68 3.3.2. Civil Disorder ....................................................................................................................... -

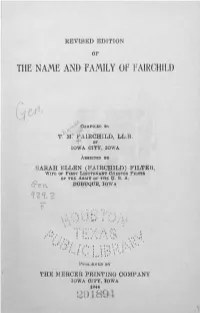

The Name and Family of Fairchild

REVISED EDITION OF THE NAME AND FAMILY OF FAIRCHILD tA «/-- .COMPILED BY TM.'FAIRCHILD, LL.B. OP ' IOWA CITY, IOWA ASSISTED BY SARAH ELLEN (FAIRCHILD) FILTER, WIPE OP FIRST LIEUTENANT CHESTER FILTER OP THE ARMY OP THE U. S. A. DUBUQUE, IOWA mz I * r • • * • • » < • • PUBLISHED BY THE MERCER PRINTING COMPANY IOWA CITY, IOWA 1944 201894 INDEX PART ONE Page Chapter I—The Name of Fairchild Was Derived From the Scotch Name of Fairbairn 5 Chapter II—Miscellaneous Information Regarding Mem bers of the Fairchild Family 10 Chapter III—The Heads of Families in the United States by the Name of Fairchild as Recorded by the First Census of the United States in 1790 50 Chapter IV—'Copy of the Fairchild Manuscript of the Media Research Bureau of Washington .... 54 Chapter V—Copy of the Orcutt Genealogy of the Ameri can Fairchilds for the First Four Generations After the Founding of Stratford and Settlement There in 1639 . 57 Chapter VI—The Second Generation of the American Fairchilds After Founding Stratford, Connecticut . 67 Chapter VII—The Third Generation of the American Fairchilds 71 Chapter VIII—The Fourth Generation of the American Fairchilds • 79 Chapter IX—The Extended Line of Samuel Fairchild, 3rd, and Mary (Curtiss) Fairchild, and the Fairchild Garden in Connecticut 86 Chapter X—The Lines of Descent of David Sturges Fair- child of Clinton, Iowa, and of Eli Wheeler Fairchild of Monticello, New York 95 Chapter XI—The Descendants of Moses Fairchild and Susanna (Bosworth) Fairchild, Early Settlers in the Berkshire Hills in Western Massachusetts, -

Melissa Mayhew History 586-B, Undergraduate Research Seminar on the Middle Ages Spring 2015 Instructor: Prof

1 Melissa Mayhew History 586-B, Undergraduate Research Seminar on the Middle Ages Spring 2015 Instructor: Prof. David Defries Castles of K-State Abstract: One of the most notable things about the Kansas State University campus is its abundance of castles. This paper argues that these castles were designed to match earlier buildings that were a part of medieval revival styles in architecture, particularly the Romanesque. What the medieval meant to the adopters of the Romanesque was different from the ideas of Englishness and aristocracy of the Gothic revival, yet they shared the use of medieval architecture as a statement against the standardization and cold logic of the Industrial Revolution. While the meaning and significance of the K-State castles has changed over the century or so they have existed, the differing values of what the medieval and modern symbolize still appear when new castles are built and the old ones restored. One of the most striking features of Kansas State University’s campus is the number of ‘castles’ it contains. Although these buildings are not technically castles, their towers, castellated parapets, and turrets, such as those seen on Nichols Hall and Holton Hall, stir most people to identify them with the large stone fortresses built in the Middle Ages. Most of the buildings on K-State’s campus are over a century old and while various reference books, histories, newspapers, and guides available in K-State’s Special Collections Archives helpfully say what styles the buildings are and point out that those styles were popular at the time the buildings were built, the sources do not discuss the significance of the buildings’ architectural styles.