Levels of Dialect

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

New England Phonology*

New England phonology* Naomi Nagy and Julie Roberts 1. Introduction The six states that make up New England (NE) are Vermont (VT), New Hampshire (NH), Maine (ME), Massachusetts (MA), Connecticut (CT), and Rhode Island (RI). Cases where speakers in these states exhibit differences from other American speakers and from each other will be discussed in this chapter. The major sources of phonological information regarding NE dialects are the Linguistic Atlas of New England (LANE) (Kurath 1939-43), and Kurath (1961), representing speech pat- terns from the fi rst half of the 20th century; and Labov, Ash and Boberg, (fc); Boberg (2001); Nagy, Roberts and Boberg (2000); Cassidy (1985) and Thomas (2001) describing more recent stages of the dialects. There is a split between eastern and western NE, and a north-south split within eastern NE. Eastern New England (ENE) comprises Maine (ME), New Hamp- shire (NH), eastern Massachusetts (MA), eastern Connecticut (CT) and Rhode Is- land (RI). Western New England (WNE) is made up of Vermont, and western MA and CT. The lines of division are illustrated in fi gure 1. Two major New England shibboleths are the “dropping” of post-vocalic r (as in [ka:] car and [ba:n] barn) and the low central vowel [a] in the BATH class, words like aunt and glass (Carver 1987: 21). It is not surprising that these two features are among the most famous dialect phenomena in the region, as both are characteristic of the “Boston accent,” and Boston, as we discuss below, is the major urban center of the area. However, neither pattern is found across all of New England, nor are they all there is to the well-known dialect group. -

Variations in Language Use Across Gender: Biological Versus Sociological Theories

UC Merced Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society Title Variations in Language Use across Gender: Biological versus Sociological Theories Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/1q30w4z0 Journal Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Cognitive Science Society, 28(28) ISSN 1069-7977 Authors Bell, Courtney M. McCarthy, Philip M. McNamara, Danielle S. Publication Date 2006 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Variations in Language Use across Gender: Biological versus Sociological Theories Courtney M. Bell (cbell@ mail.psyc.memphis.edu Philip M. McCarthy ([email protected]) Danielle S. McNamara ([email protected]) Institute for Intelligent Systems University of Memphis Memphis, TN38152 Abstract West, 1975; West & Zimmerman, 1983) and overlap We examine gender differences in language use in light of women’s speech (Rosenblum, 1986) during conversations the biological and social construction theories of gender. than the reverse. On the other hand, other research The biological theory defines gender in terms of biological indicates no gender differences in interruptions (Aries, sex resulting in polarized and static language differences 1996; James & Clarke, 1993) or insignificant differences based on sex. The social constructionist theory of gender (Anderson & Leaper, 1998). However, potentially more assumes gender differences in language use depend on the context in which the interaction occurs. Gender is important than citing the differences, is positing possible contextually defined and fluid, predicting that males and explanations for why they might exist. We approach that females use a variety of linguistic strategies. We use a problem here by testing the biological and social qualitative linguistic approach to investigate gender constructionist theories (Bergvall, 1999; Coates & differences in language within a context of marital conflict. -

Contesting Regimes of Variation: Critical Groundwork for Pedagogies of Mobile Experience and Restorative Justice

Robert W. Train Sonoma State University, California CONTESTING REGIMES OF VARIATION: CRITICAL GROUNDWORK FOR PEDAGOGIES OF MOBILE EXPERIENCE AND RESTORATIVE JUSTICE Abstract: This paper examines from a critical transdisciplinary perspective the concept of variation and its fraught binary association with standard language as part of the conceptual toolbox and vocabulary for language educators and researchers. “Variation” is shown to be imbricated a historically-contingent metadiscursive regime in language study as scientific description and education supporting problematic speaker identities (e.g., “non/native”, “heritage”, “foreign”) around an ideology of reduction through which complex sociolinguistic and sociocultural spaces of diversity and variability have been reduced to the “problem” of governing people and spaces legitimated and embodied in idealized teachers and learners of languages invented as the “zero degree of observation” (Castro-Gómez 2005; Mignolo 2011) in ongoing contexts of Western modernity and coloniality. This paper explores how regimes of variation have been constructed in a “sociolinguistics of distribution” (Blommaert 2010) constituted around the delimitation of borders—linguistic, temporal, social and territorial—rather than a “sociolinguistics of mobility” focused on interrogating and problematizing the validity and relevance of those borders in a world characterized by diverse transcultural and translingual experiences of human flow and migration. This paper reframes “variation” as mobile modes-of-experiencing- the-world in order to expand the critical, historical, and ethical vocabularies and knowledge base of language educators and lay the groundwork for pedagogies of experience that impact human lives in the service of restorative social justice. Keywords: metadiscursive regimes w sociolinguistic variation w standard language w sociolinguistics of mobility w pedagogies of experience Train, Robert W. -

Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions

http://lexikos.journals.ac.za; https://doi.org/10.5788/30-1-1604 Normative Labels in Two Lexicographic Traditions: A Slovene–English Case Study Marjeta Vrbinc, Faculty of Arts, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Danko Šipka, School for International Letters and Cultures, Arizona State University, Tempe Campus, USA ([email protected]) and Alenka Vrbinc, School of Economics and Business, University of Ljubljana, Slovenia ([email protected]) Abstract: This article presents and discusses the findings of a study conducted with the users of Slovene and American monolingual dictionaries. The aim was to investigate how native speakers of Slovene and American English interpret select normative labels in monolingual dictionaries. The data were obtained by questionnaires developed to elicit monolingual dictionary users' attitudes toward normative labels and the effects the labels have on dictionary users. The results show that a higher level of prescriptivism in the Slovene linguistic culture is reflected in the Slovene respon- dents' perception of the labels (for example, a stronger effect of the normative labels, a higher approval for the claim about usefulness of the labels, a considerably lower general level of accep- tance for the standard language) when compared with the American respondents' perception, since the American linguistic culture tends to be more descriptive. However, users often seek answers to their linguistic questions in dictionaries, which means that they expect at least a certain degree of normativity. Therefore, a balance between descriptive and prescriptive approaches should be found, since both of them affect the users. Keywords: GENERAL MONOLINGUAL DICTIONARY, PRESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVITY, DESCRIPTIVISM, NORMATIVE LABELS, PRIMARY EXCLUSION LABELS, SECONDARY EXCLUSION LABELS, USE OF LABELS, USEFULNESS OF LABELS, (UN)LABELED ENTRIES Opsomming: Normatiewe etikette in twee leksikografiese tradisies: 'n Sloweens–Engelse gevallestudie. -

Intonation of Sicilian Among Southern Italo-Romance Dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano

Intonation of Sicilian among Southern Italo-romance dialects Valentina De Iacovo, Antonio Romano Laboratorio di Fonetica Sperimentale “A. Genre”, Univ. degli Studi di Torino, Italy [email protected] , [email protected] ABSTRACT At a second stage, we select the most frequent pattern found in the data for each modality (also closest to the Dialects of Italy are a good reference to show how description provided by [10]) and compare it with prosody plays a specific role in terms of diatopic other Southern Italo-romance varieties with the aim variation. Although previous experimental studies of verifying a potential similarity with other Southern have contributed to classify a selection of some and Upper Southern varieties. profiles on the basis of some Italian samples from this region and a detailed description is available for some 2. METHODOLOGY dialects, a reference framework is still missing. In this paper a collection of Southern Italo-romance varieties 2.1. Materials and speakers is presented: based on a dialectometrical approach, For the first experiment, data was part of a more we attempt to illustrate a more detailed classification extensive corpus available online which considers the prosodic proximity between (http://www.lfsag.unito.it/ark/trm_index.html, see Sicilian samples and other dialects belonging to the also [4]). We select 31 out of 40 recordings Upper Southern and Southern dialectal areas. The representing 21 Sicilian dialects (9 of them were results, based on the analysis of various corpora, discarded because their intonation was considered show the presence of different prosodic profiles either too close to Standard Italian or underspecified regarding the Sicilian area and a distinction among in terms of prosodic strength). -

12 English Dialect Input to the Caribbean

12 English dialect input to the Caribbean 1 Introduction There is no doubt that in the settlement of the Caribbean area by English speakers and in the rise of varieties of English there, the question of regional British input is of central importance (Rickford 1986; Harris 1986). But equally the two other sources of specific features in anglophone varieties there, early creolisation and independent developments, have been given continued attention by scholars. Opinions are still divided on the relative weight to be accorded to these sources. The purpose of the present chapter is not to offer a description of forms of English in the Caribbean – as this would lie outside the competence of the present author, see Holm (1994) for a resum´ e–b´ ut rather to present the arguments for regional British English input as the historical source of salient features of Caribbean formsofEnglish and consider these arguments in the light of recent research into both English in this region and historical varieties in the British Isles. This is done while explicitly acknowledging the role of West African input to forms of English in this region. This case has been argued eloquently and well, since at least Alleyne (1980) whose views are shared by many creolists, e.g. John Rickford. But the aim of the present volume, and specifically of the present chapter, is to consider overseas varieties of English in the light of possible continuity of input formsofEnglish from the British Isles. This concern does not seek to downplay West African input and general processes of creolisation, which of course need to be specified in detail,1 butrather tries to put the case for English input and so complement other views already available in the field. -

CHAPTER 2 Registers of Language

Duranti / Companion to Linguistic Anthropology Final 12.11.2003 1:28pm page 23 Registers of CHAPTER 2 Language Asif Agha 1INTRODUCTION Language users often employ labels like ‘‘polite language,’’ ‘‘informal speech,’’ ‘‘upper-class speech,’’ ‘‘women’s speech,’’ ‘‘literary usage,’’ ‘‘scientific term,’’ ‘‘reli- gious language,’’ ‘‘slang,’’ and others, to describe differences among speech forms. Metalinguistic labels of this kind link speech repertoires to enactable pragmatic effects, including images of the person speaking (woman, upper-class person), the relationship of speaker to interlocutor (formality, politeness), the conduct of social practices (religious, literary, or scientific activity); they hint at the existence of cultural models of speech – a metapragmatic classification of discourse types – linking speech repertoires to typifications of actor, relationship, and conduct. This is the space of register variation conceived in intuitive terms. Writers on language – linguists, anthropologists, literary critics – have long been interested in cultural models of this kind simply because they are of common concern to language users. Speakers of any language can intuitively assign speech differences to a space of classifications of the above kind and, correspondingly, can respond to others’ speech in ways sensitive to such distinctions. Competence in such models is an indispensable resource in social interaction. Yet many features of such models – their socially distributed existence, their ideological character, the way in which they motivate tropes of personhood and identity – have tended to puzzle writers on the subject of registers. I will be arguing below that a clarification of these issues – indeed the very study of registers – requires attention to reflexive social processes whereby such models are formulated and disseminated in social life and become available for use in interaction by individuals. -

Downloaded an Applet That Would Allow the Recordings to Be Collected Remotely

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report Title A Survey of English Vowel Spaces of Asian American Californians Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/4w84m8k4 Journal UC Berkeley PhonLab Annual Report, 12(1) ISSN 2768-5047 Author Cheng, Andrew Publication Date 2016 DOI 10.5070/P7121040736 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UC Berkeley Phonetics and Phonology Lab Annual Report (2016) A Survey of English Vowel Spaces of Asian American Californians Andrew Cheng∗ May 2016 Abstract A phonetic study of the vowel spaces of 535 young speakers of Californian English showed that participation in the California Vowel Shift, a sound change unique to the West Coast region of the United States, varied depending on the speaker's self- identified ethnicity. For example, the fronting of the pre-nasal hand vowel varied by ethnicity, with White speakers participating the most and Chinese and South Asian speakers participating less. In another example, Korean and South Asian speakers of Californian English had a more fronted foot vowel than the White speakers. Overall, the study confirms that CVS is present in almost all young speakers of Californian English, although the degree of participation for any individual speaker is variable on account of several interdependent social factors. 1 Introduction This is a study on the English spoken by Americans of Asian descent living in California. Specifically, it will look at differences in vowel qualities between English speakers of various ethnic -

Deciphering L33tspeak

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy Thesis Deciphering L33t5p34k Internet Slang on Message Boards Supervisor: Master Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of Prof. Anne-Marie Simon-Vandenbergen the requirements for the degree of ―Master in de Taal- en Letterkunde – Afstudeerrichting: Engels‖ By Eveline Flamand 2007-2008 i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my promoter, professor Anne-Marie Vandenbergen, for agreeing on supervising this perhaps unconventional thesis. Secondly I would like to mention my brother, who recently graduated as a computer engineer and who has helped me out when my knowledge on electronic technology did not suffice. Niels Cuelenaere also helped me out by providing me with some material and helping me with a Swedish translation. The people who came up to me and told me they would like to read my thesis, have encouraged me massively. In moments of doubt, they made me realize that there is an audience for this kind of research, which made me even more determined to finish this thesis successfully. Finally, I would also like to mention the members of the Filologica forum, who have been an inspiration for me. ii Index 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................... 1 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................... 1 2.1 4chan ............................................................................................................................... -

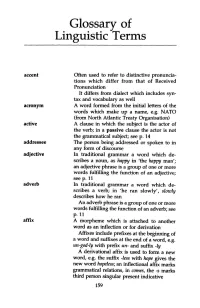

Glossary of Linguistic Terms

Glossary of Linguistic Terms accent Often used to refer to distinctive pronuncia tions which differ from that of Received Pronunciation It differs from dialect which includes syn tax and vocabulary as well acronym A word formed from the initial letters of the words which make up a name, e.g. NATO (from North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) active A clause in which the subject is the actor of the verb; in a passive clause the actor is not the grammatical subject; seep. 14 addressee The person being addressed or spoken to in any form of discourse adjective In traditional grammar a word which de scribes a noun, as happy in 'the happy man'; an adjective phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adjective; seep. 11 adverb In t:r:aditional grammar a word which de scribes a verb; in 'he ran slowly', slowly describes how he ran An adverb phrase is a group of one or more words fulfilling the function of an adverb; see p. 11 affix A morpheme which is attached to another word as an inflection or for derivation Affixes include prefixes at the beginning of a word and suffixes at the end of a word, e.g. un-god-ly with prefix un- and suffix -ly A derivational affix is used to form a new word, e.g. the suffix -less with hope gives the new word hopeless; an inflectional affix marks grammatical relations, in comes, the -s marks third person singular present indicative 159 160 Glossary alliteration The repetition of the same sound at the beginning of two or more words in close proximity, e.g. -

The Effect of Appalachian Regional Dialect on Performance Appraisal and Leadership Perceptions" (2014)

Eastern Kentucky University Encompass Online Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship January 2014 The ffecE t of Appalachian Regional Dialect on Performance Appraisal and Leadership Perceptions Amie Sparks Ball Eastern Kentucky University Follow this and additional works at: https://encompass.eku.edu/etd Part of the Cognitive Psychology Commons, and the Social Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Ball, Amie Sparks, "The Effect of Appalachian Regional Dialect on Performance Appraisal and Leadership Perceptions" (2014). Online Theses and Dissertations. 203. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/203 This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Encompass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Online Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Encompass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE EFFECT OF APPALACHIAN REGIONAL DIALECT ON PERFROMANCE APPRASAL AND LEADERSHIP PERCEPTIONS By Amie Sparks Ball Master of Science Eastern Kentucky University Richmond, Kentucky 2014 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Eastern Kentucky University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE May, 2014 Copyright © Amie Sparks Ball, 2014 All rights reserved ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my thesis chair, Dr. Catherine Clement, for her help and guidance. I would also like to thank my other committee members, Dr. Yoshie Nakai and Dr. Jonathan Gore, for their assistance over the past two years. I would like to express my thanks to my husband, Tyler, and my parents, John and Sheila, for their support and encouragement throughout this process. iii Abstract Speakers of Appalachian English face unique difficulties in the workplace. -

Attitudes Towards the Safeguarding of Minority Languages and Dialects in Modern Italy

ATTITUDES TOWARDS THE SAFEGUARDING OF MINORITY LANGUAGES AND DIALECTS IN MODERN ITALY: The Cases of Sardinia and Sicily Maria Chiara La Sala Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds Department of Italian September 2004 This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to assess attitudes of speakers towards their local or regional variety. Research in the field of sociolinguistics has shown that factors such as gender, age, place of residence, and social status affect linguistic behaviour and perception of local and regional varieties. This thesis consists of three main parts. In the first part the concept of language, minority language, and dialect is discussed; in the second part the official position towards local or regional varieties in Europe and in Italy is considered; in the third part attitudes of speakers towards actions aimed at safeguarding their local or regional varieties are analyzed. The conclusion offers a comparison of the results of the surveys and a discussion on how things may develop in the future. This thesis is carried out within the framework of the discipline of sociolinguistics. ii DEDICATION Ai miei figli Youcef e Amil che mi hanno distolto