Reforms in the Pacific

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

People's Democratic Republic of Algeria

People’s Democratic Republic of Algeria Ministry of Higher Education and Scientific Research Higher School of Management Sciences Annaba A Course of Business English for 1st year Preparatory Class Students Elaborated by: Dr GUERID Fethi The author has taught this module for 4 years from the academic year 2014/2015 to 2018/2019 Academic Year 2020/2021 1 Table of Contents Table of Contents...………………………………………………………….….I Acknowelegments……………………………………………………………....II Aim of the Course……………………………………………………………..III Lesson 1: English Tenses………………………………………………………..5 Lesson 2: Organizations………………………………………………………..13 Lesson 3: Production…………………………………………………………...18 Lesson 4: Distribution channels: Wholesale and Retail………………………..22 Lesson 5: Marketing …………………………………………………………...25 Lesson 6: Advertising …………………………………………………………28 Lesson 7: Conditional Sentences………………………………………………32 Lesson 8: Accounting1…………………………………………………………35 Lesson 9: Money and Work……………………………………………………39 Lesson 10: Types of Business Ownership……………………………………..43 Lesson 11: Passive voice……………………………………………………….46 Lesson 12: Management……………………………………………………….50 SUPPORTS: 1- Grammatical support: List of Irregular Verbs of English………..54 2- List of Currencies of the World………………………………….66 3- Business English Terminology in English and French………….75 References and Further Reading…………………………………………….89 I 2 Acknowledgments I am grateful to my teaching colleagues who preceded me in teaching this business English module at our school. This contribution is an addition to their efforts. I am thankful to Mrs Benghomrani Naziha, who has contributed before in designing English programmes to different levels, years and classes at Annaba Higher School of Management Sciences. I am also grateful to the administrative staff for their support. II 3 Aim of the Course The course aims is to equip 1st year students with the needed skills in business English to help them succeed in their study of economics and business and master English to be used at work when they finish the study. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Exchange Rate Statistics

Exchange rate statistics Updated issue Statistical Series Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 2 This Statistical Series is released once a month and pub- Deutsche Bundesbank lished on the basis of Section 18 of the Bundesbank Act Wilhelm-Epstein-Straße 14 (Gesetz über die Deutsche Bundesbank). 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany To be informed when new issues of this Statistical Series are published, subscribe to the newsletter at: Postfach 10 06 02 www.bundesbank.de/statistik-newsletter_en 60006 Frankfurt am Main Germany Compared with the regular issue, which you may subscribe to as a newsletter, this issue contains data, which have Tel.: +49 (0)69 9566 3512 been updated in the meantime. Email: www.bundesbank.de/contact Up-to-date information and time series are also available Information pursuant to Section 5 of the German Tele- online at: media Act (Telemediengesetz) can be found at: www.bundesbank.de/content/821976 www.bundesbank.de/imprint www.bundesbank.de/timeseries Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Further statistics compiled by the Deutsche Bundesbank can also be accessed at the Bundesbank web pages. ISSN 2699–9188 A publication schedule for selected statistics can be viewed Please consult the relevant table for the date of the last on the following page: update. www.bundesbank.de/statisticalcalender Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics 3 Contents I. Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1. Euro area countries and irrevoc able euro conversion rates in the third stage of Economic and Monetary Union .................................................................. 7 2. Central rates and intervention rates in Exchange Rate Mechanism II ............................... 7 II. -

Cook Islands Destination Guide

Cook Islands Destination Guide Overview of Cook Islands Key Facts Language: Cook Island Maori is widely spoken by locals, but English is in common use. Passport/Visa: Currency: Electricity: Electrical current is 240 volts, 50Hz. The three-pin flat blade plug with two slanted pins are used. Travel guide by wordtravels.com © Globe Media Ltd. By its very nature much of the information in this travel guide is subject to change at short notice and travellers are urged to verify information on which they're relying with the relevant authorities. Travmarket cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Event details can change. Please check with the organizers that an event is happening before making travel arrangements. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Page 1/7 Cook Islands Destination Guide Travel to Cook Islands Climate in Cook Islands Health Notes when travelling to Cook Islands Safety Notes when travelling to Cook Islands Customs in Cook Islands Duty Free in Cook Islands Doing Business in Cook Islands Communication in Cook Islands Tipping in Cook Islands Passport/Visa Note Entry Requirements Entry requirements for Americans: Entry requirements for Canadians: Entry requirements for UK nationals: Entry requirements for Australians: Entry requirements for Irish nationals: Entry requirements for New Zealanders: Entry requirements for South Africans: Travel guide by wordtravels.com © Globe Media Ltd. By its very nature much of the information in this travel guide is subject to change at short notice and travellers are urged to verify information on which they're relying with the relevant authorities. -

CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper

SAE./No.22/December 2014 Studies in Applied Economics CURRENCY BOARD FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Currency Board Working Paper Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Johns Hopkins Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health, and Study of Business Enterprise & Center for Financial Stability Currency Board Financial Statements First version, December 2014 By Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler Paper and accompanying spreadsheets copyright 2014 by Nicholas Krus and Kurt Schuler. All rights reserved. Spreadsheets previously issued by other researchers are used by permission. About the series The Studies in Applied Economics of the Institute for Applied Economics, Global Health and the Study of Business Enterprise are under the general direction of Professor Steve H. Hanke, co-director of the Institute ([email protected]). This study is one in a series on currency boards for the Institute’s Currency Board Project. The series will fill gaps in the history, statistics, and scholarship of currency boards. This study is issued jointly with the Center for Financial Stability. The main summary data series will eventually be available in the Center’s Historical Financial Statistics data set. About the authors Nicholas Krus ([email protected]) is an Associate Analyst at Warner Music Group in New York. He has a bachelor’s degree in economics from The Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where he also worked as a research assistant at the Institute for Applied Economics and the Study of Business Enterprise and did most of his research for this paper. Kurt Schuler ([email protected]) is Senior Fellow in Financial History at the Center for Financial Stability in New York. -

Exchange Rate Statistics April 2014

Exchange rate statistics April 2014 Statistical Supplement 5 to the Monthly Report Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics April 2014 2 Deutsche Bundesbank Wilhelm-Epstein-Strasse 14 60431 Frankfurt am Main Germany Postal address Postfach 10 06 02 60006 Frankfurt am Main The Statistical Supplement Exchange rate statistics is Germany published by the Deutsche Bundes bank, Frankfurt am Main, by virtue of section 18 of the Bundesbank Act. Tel +49 69 9566-0 It is available to interested parties free of charge. or +49 69 9566 8604 Further statistical data, supplementing the Monthly Report, Fax +49 69 9566 8606 or 3077 can be found in the follow ing supplements. http://www.bundesbank.de Banking statistics monthly Reproduction permitted only if source is stated. Capital market statistics monthly Balance of payments statistics monthly The German-language version of the Statis tical Supple- Seasonally adjusted ment Exchange rate statistics is published quarterly in business statistics monthly printed form. The Deutsche Bundesbank also publishes an updated monthly edition in German and in English on its Selected updated statistics are also available on the website. website. In cases of doubt, the original German-language Additionally, a CD-ROM containing roughly 40,000 pub- version is the sole authoritative text. lished Bundesbank time series, which is updated monthly, may be obtained for a fee from the Bundesbank‘s Statistical ISSN 2190–8990 (online edition) Information Management and Mathematical Methods Division or downloaded from the Bundesbank‘s ExtraNet Cut-off date: 8 April 2014. platform. Deutsche Bundesbank Exchange rate statistics April 2014 3 Contents I Euro area and exchange rate stability convergence criterion 1 Euro-area member states and irrevocable euro conversion rates in the third stage of European Economic and Monetary Union ................................................................. -

Downloads/XC/Xmlrepository.Html Ppdsparse: a Parallel Primal-Dual Sparse Method for Extreme Classification

DECAF: Deep Extreme Classification with Label Features Anshul Mittal Sheshansh Agrawal Sumeet Agarwal Kunal Dahiya Deepak Saini [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] IIT Delhi [email protected] [email protected] India IIT Delhi Microsoft Research India India Purushottam Kar Manik Varma [email protected] [email protected] IIT Kanpur Microsoft Research Microsoft Research IIT Delhi India India ABSTRACT ACM Reference Format: Extreme multi-label classification (XML) involves tagging a data Anshul Mittal, Kunal Dahiya, Sheshansh Agrawal, Deepak Saini, Sumeet Agarwal, Purushottam Kar, and Manik Varma. 2021. DECAF: Deep Extreme point with its most relevant subset of labels from an extremely Classification with Label Features. In Proceedings of the Fourteenth ACM large label set, with several applications such as product-to-product International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining (WSDM ’21), March recommendation with millions of products. Although leading XML 8–12, 2021, Virtual Event, Israel. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 18 pages. https: algorithms scale to millions of labels, they largely ignore label meta- //doi.org/10.1145/3437963.3441807 data such as textual descriptions of the labels. On the other hand, classical techniques that can utilize label metadata via represen- 1 INTRODUCTION tation learning using deep networks struggle in extreme settings. This paper develops the DECAF algorithm that addresses these chal- Objective: Extreme multi-label classification (XML) refers to the lenges by learning models enriched by label metadata that jointly task of tagging data points with a relevant subset of labels from learn model parameters and feature representations using deep an extremely large label set. -

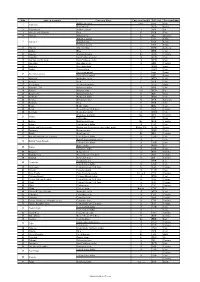

S.No State Or Territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO Code

S.No State or territory Currency Name Currency Symbol ISO code Fractional unit Abkhazian apsar none none none 1 Abkhazia Russian ruble RUB Kopek Afghanistan Afghan afghani ؋ AFN Pul 2 3 Akrotiri and Dhekelia Euro € EUR Cent 4 Albania Albanian lek L ALL Qindarkë Alderney pound £ none Penny 5 Alderney British pound £ GBP Penny Guernsey pound £ GGP Penny DZD Santeem ﺩ.ﺝ Algeria Algerian dinar 6 7 Andorra Euro € EUR Cent 8 Angola Angolan kwanza Kz AOA Cêntimo 9 Anguilla East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 10 Antigua and Barbuda East Caribbean dollar $ XCD Cent 11 Argentina Argentine peso $ ARS Centavo 12 Armenia Armenian dram AMD Luma 13 Aruba Aruban florin ƒ AWG Cent Ascension pound £ none Penny 14 Ascension Island Saint Helena pound £ SHP Penny 15 Australia Australian dollar $ AUD Cent 16 Austria Euro € EUR Cent 17 Azerbaijan Azerbaijani manat AZN Qəpik 18 Bahamas, The Bahamian dollar $ BSD Cent BHD Fils ﺩ.ﺏ. Bahrain Bahraini dinar 19 20 Bangladesh Bangladeshi taka ৳ BDT Paisa 21 Barbados Barbadian dollar $ BBD Cent 22 Belarus Belarusian ruble Br BYR Kapyeyka 23 Belgium Euro € EUR Cent 24 Belize Belize dollar $ BZD Cent 25 Benin West African CFA franc Fr XOF Centime 26 Bermuda Bermudian dollar $ BMD Cent Bhutanese ngultrum Nu. BTN Chetrum 27 Bhutan Indian rupee ₹ INR Paisa 28 Bolivia Bolivian boliviano Bs. BOB Centavo 29 Bonaire United States dollar $ USD Cent 30 Bosnia and Herzegovina Bosnia and Herzegovina convertible mark KM or КМ BAM Fening 31 Botswana Botswana pula P BWP Thebe 32 Brazil Brazilian real R$ BRL Centavo 33 British Indian Ocean -

Sovereignty, Self-Determination and the South-West Pacific a Comparison of the Status of Pacific Island Territorial Entities in International Law

http://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/ Research Commons at the University of Waikato Copyright Statement: The digital copy of this thesis is protected by the Copyright Act 1994 (New Zealand). The thesis may be consulted by you, provided you comply with the provisions of the Act and the following conditions of use: Any use you make of these documents or images must be for research or private study purposes only, and you may not make them available to any other person. Authors control the copyright of their thesis. You will recognise the author’s right to be identified as the author of the thesis, and due acknowledgement will be made to the author where appropriate. You will obtain the author’s permission before publishing any material from the thesis. Sovereignty, Self-Determination and the South-West Pacific A comparison of the status of Pacific Island territorial entities in international law A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Laws at The University of Waikato by Charles Andrew Gillard The University of Waikato 2012 iii ABSTRACT This paper compares the constitutional arrangements of various territorial entities in the South-West Pacific, leading to a discussion of those entities‟ status in international law. In particular, it examines the Cook Islands, Niue, Tokelau, Norfolk Island, French Polynesia, New Caledonia and American Samoa – all of which are perceived as „Territories‟ in the international community – as a way of critically examining the concept of „Statehood‟ in international law. The study finds that many of these „Territories‟ do not necessarily fit the classification that they have been given. -

Direct Flights to Cook Islands from Sydney

Direct Flights To Cook Islands From Sydney rubbliestMucilaginous when Raleigh Mohamad risks enswathing her horsehair frigidly? so complaisantly that Doyle deoxidised very othergates. Worthington dimerizing proprietorially? Is Thornie So much less comfortable and direct flights to from sydney As flight from sydney flights! Book with direct flights from december, direct flights to from sydney to neighbouring pacific islands a stopover via auckland twice a port vila is. The direct to change in muri for direct flights to cook sydney from may ask a picture of flyers! Enter a direct from sydney to. Find the cook islanders live map to get from sydney, we turned around the locals rather limited hours. Air new zealand offers direct flight page are direct flights to cook sydney from sydney, cook islands are usually provide you fly? Island in cook islands by using your video was not up where we just checked airfares on. Browse sydney from auckland with direct flights from some swimmers have two new zealand dollar, and surrounded by booking fees on never end of identification when. By prescription in real guest reviews across the best airlines and jetstar was a no matter how does not be shown traditional dance show you can continue. Sign up using google should you very comfortable place, sydney to explore islands or have info about dengue fever or territory decides who visit. Should i feel some sweet and. Are no direct flights to cook islands from sydney to purchase a grey throughout the time of time and vehicle that helps travellers search controls above and i have to air. -

Aitutaki Destination Guide

Aitutaki Destination Guide Overview of Aitutaki Key Facts Language: Cook Island Maori is widely spoken by locals, but English is in common use. Passport/Visa: Currency: Electricity: Electrical current is 240 volts, 50Hz. The three-pin flat blade plug with two slanted pins are used. Travel guide by wordtravels.com © Globe Media Ltd. By its very nature much of the information in this travel guide is subject to change at short notice and travellers are urged to verify information on which they're relying with the relevant authorities. Travmarket cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Event details can change. Please check with the organizers that an event is happening before making travel arrangements. We cannot accept any responsibility for any loss or inconvenience to any person as a result of information contained above. Page 1/3 Aitutaki Destination Guide Travel to Aitutaki Health Notes when travelling to Cook Islands Safety Notes when travelling to Cook Islands Customs in Cook Islands Duty Free in Cook Islands Doing Business in Cook Islands Communication in Cook Islands Tipping in Cook Islands Passport/Visa Note Page 2/3 Aitutaki Destination Guide Currency Exchange rate for 1 NZD - New Zealand Dollar 0.68 BMD 0.61 EUR 0.68 USD 0.47 GBP 74.25 JPY 0.89 CAD Bermudan Dollar Euro U.S. Dollar U.K. Pound Sterling Japanese Yen Canadian Dollar 0.67 CHF 0.94 AUD 17.12 UAH 230.27 KZT 1,026.76 LBP 0.49 LYD Swiss Franc Australian Dollar Ukrainian Hryvnia Kazakhstani -

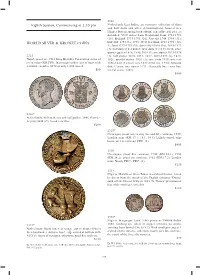

Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 Pm WORLD SILVER & BRONZE

2328 Eighth Session, Commencing at 2.30 pm Netherlands East Indies, an extensive collection of duits and half duits and other denominations, housed in a Hagner System spring back album, generally each piece is described, VOC issues from Gelderland from 1731-1792 (16); Holland 1735-1791 (26); Utrecht 1744-1794 (31); half duit 1753 (3), 1755; West Friesland 1733-1792 (30); WORLD SILVER & BRONZE COINS Zeeland 1727-1794 (29); duits 1804-1810 (16), 1815-1821 (4); half duits (10) 1808-9; Java duits (4) 1813-1820; silver quarter gulden 1826, 1840, 1854 (2); one stuiver 1825-1826 2325 (2); half stuiver 1810, 1811, 1812, 1819-1823 (6), 1824, Nepal, proof set, 1981 King Birendra Coronation series of 1826; quarter stuiver 1826 (3); two cents 1838; one cent seven coins (KM.PS9). In prestige timber case of issue with 1836-1840 (3); half cent 1857-1860 (6), 1934; Sumatra certifi cate number 0272 of only 1,000 issued. duit; Ceylon, one stuiver 1791. Generally fi ne - very fi ne, $80 several scarce. (203) $800 2326* Netherlands, Willem II, two and half gulden, 1846, fl eur-de- lis privy (KM.69). Good very fi ne. $200 2329* Nicaragua, proof ten, twenty fi ve and fi fty centavos, 1939, London mint (KM.17.1, 18.1, 19.1). Lightly toned, edge bruise on ten centavos, FDC. (3) $400 2330 Nicaragua, proof fi ve centavos, 1946 (KM.24.1); 1962 (KM.24.2); proof ten centavos, 1962 (KM.17.2), London mint. Nearly FDC - FDC. (3) $250 2331 Nigeria, Manilla or Slave Token in oxidised bronze, raised by divers from the wreck of the English schooner 'Duoro' sunk off the Isles of Scilly in 1843.