Anatolii Lunacharskii and the Soviet Theater

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

TAPE SUBJECT LOG NAMELIST Chronological Review Boldface = Deceased Revised 8 December 2003

NIXON PRESIDENTIAL MATERIALS STAFF TAPE SUBJECT LOG NAMELIST Chronological Review Boldface = deceased Revised 8 December 2003 A Prince [AAge] of Denmark: 806 Aaron, Henry L. (“Hank”): 55, 476, 488, 797 Aaronson, J. Hugo: 581 Abad, Francis L.: 602 Abate, Joseph: 453 Abbitt, Watkins M.: 15, 581 Abbott, Samuel A. (“Sammy”): 249 Abdulla, Abdul R.: 116 Abdnor, E. James: 744 Abel, I[lorwith] W[ilbur]: 15, 21, 63, 64, 72, 79, 81, 110, 111, 120, 128, 146, 269, 301, 336, 337, 479, 530, 531, 532, 534, 540, 541, 551, 553, 587, 591, 599, 610, 622, 623, 640, 679, 698, 706, 794 Abernathy, Ralph: 539 Abernethy, Robert G.: 27, 575, 754 Abernethy, Thomas G.: 6, 55, 134, 492, 581 Ablard, Charles D.: 102 Ablum, Floyd: 1 Abourezk, James: 486 Abplanalp, Robert H.: 11, 17, 24, 31, 42, 137, 140, 190, 220, 251, 274, 285, 311, 330, 339, 344, 347, 353, 450, 455, 462, 464, 466, 513, 518, 520, 571, 576, 584, 597, 599, 649, 653, 660, 662, 666, 695, 702, 705, 722, 724, 725, 734, 739, 745, 747, 759, 760, 798 Abrahams, Albert E.: 82, 96, 376, 571 Abrams, Gen. Creighton W., Jr.: 1, 4, 19, 20, 22, 23, 24, 31, 32, 50, 61, 62, 131, 133, 149, 151, 181, 189, 191, 246, 255, 298, 299, 317, 329, 330, 331, 332, 333, 334, 335, 336, 337, 338, 339, 354, 367, 368, 371, 374, 449, 451, 456, 457, 458, 459, 462, 464, 465, 467, 468, 470, 471, 472, 474, 476, 477, 478, 481, 482, 484, 498, 500, 504, 505, 507, 508, 511, 518, 520, 522, 529, 540, 543, 547, 548, 549, 558, 571, 574, 575, 635, 647, 648, 652, 655, 665, 673, 681, 685, 700, 701, 702, 703, 705, 706, 707, 708, 709, 710, 711, 713, 715, -

Crowds and Democracy

Crowds and Democracy THE IDEA AND IMAGE OF THE MASSES FROM REVOLUTION TO FASCISM Stefan Jonsson Columbia University Press yf New York CONTENTS List of Illustrations xi Preface xv 1. Introducing the Masses: Vienna, 15 July 1927 1 (ELIAS CANETTI—ALFRED VIERKANDT— HANMAH ARENDT — KARL KRAUS—HEIMITO VON DODERER) 1. Shooting Psychosis 1 2. Not a Word About the Bastille 6 3. Explaining the Crowd 16 4. Representing Social Passions 23 5. A Work of Madness 28 6. Invincibles 33 7. Mirror for Princes 37 8. Workers on the Run 41 9. Lashing 47 Vlll LVJINlLiNIO 2. Authority Versus Anarchy: Allegories of the Mass in Sociology and Literature 51 (GEORG SIMMEL— WERNER SOMBART— FRITZ LANG — LEOPOLD VON WIESE— WILHELM VLEUGELS— GERHARD COLM— MAX WEBER—THEODOR GEIGER—AUGUST SAWDER- HERMANN BROCH —ERNST TOLLER— RAINER MARIA RILKE) 10. The Missing Chapter 51 11. Georg Simmel's Masses 54 12. In Metropolis 61 13. The Architecture of Society 67 14. Steak Tartare 73 15. Delta Formations 80 16. Alarm Bells of History 84 17. Sleepwalkers 92 18.1 Am Mass 105 19. Rilke in the Revolution 115 3. The Revolving Nature of the Social: Primal Hordes and Crowds Without Qualities 119 (SIGMUND FREUD —HANS KELSEN—THEODOR ADORNO — WILHELM REICH —SIEGFRIED KRACAUER —BE11TOLT HRECHT — ALFRED DOBLIN —GEORG GROSZ—ROBERT Ml SIL) 20. Sigmund Freud Between Individual and Society 119 21. Masses Inside 122 22. In Love with Many 126 23. Primal Hordes 131 24. Masses and Myths 139 25. The Destruction of the Person 142 26. The Flaneur—Medium of Modernity 146 27. Ornaments of the People 152 28. -

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907)

Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2013 © 2013 BuYun Chen All rights reserved ABSTRACT Dressing for the Times: Fashion in Tang Dynasty China (618-907) BuYun Chen During the Tang dynasty, an increased capacity for change created a new value system predicated on the accumulation of wealth and the obsolescence of things that is best understood as fashion. Increased wealth among Tang elites was paralleled by a greater investment in clothes, which imbued clothes with new meaning. Intellectuals, who viewed heightened commercial activity and social mobility as symptomatic of an unstable society, found such profound changes in the vestimentary landscape unsettling. For them, a range of troubling developments, including crisis in the central government, deep suspicion of the newly empowered military and professional class, and anxiety about waste and obsolescence were all subsumed under the trope of fashionable dressing. The clamor of these intellectuals about the widespread desire to be “current” reveals the significant space fashion inhabited in the empire – a space that was repeatedly gendered female. This dissertation considers fashion as a system of social practices that is governed by material relations – a system that is also embroiled in the politics of the gendered self and the body. I demonstrate that this notion of fashion is the best way to understand the process through which competition for status and self-identification among elites gradually broke away from the imperial court and its system of official ranks. -

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-Century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London P

The Ideal of Ensemble Practice in Twentieth-century British Theatre, 1900-1968 Philippa Burt Goldsmiths, University of London PhD January 2015 1 I hereby declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own and has not been and will not be submitted, in whole or in part, to any other university for the award of any other degree. Philippa Burt 2 Acknowledgements This thesis benefitted from the help, support and advice of a great number of people. First and foremost, I would like to thank Professor Maria Shevtsova for her tireless encouragement, support, faith, humour and wise counsel. Words cannot begin to express the depth of my gratitude to her. She has shaped my view of the theatre and my view of the world, and she has shown me the importance of maintaining one’s integrity at all costs. She has been an indispensable and inspirational guide throughout this process, and I am truly honoured to have her as a mentor, walking by my side on my journey into academia. The archival research at the centre of this thesis was made possible by the assistance, co-operation and generosity of staff at several libraries and institutions, including the V&A Archive at Blythe House, the Shakespeare Centre Library and Archive, the National Archives in Kew, the Fabian Archives at the London School of Economics, the National Theatre Archive and the Clive Barker Archive at Rose Bruford College. Dale Stinchcomb and Michael Gilmore were particularly helpful in providing me with remote access to invaluable material held at the Houghton Library, Harvard and the Harry Ransom Center at the University of Texas, Austin, respectively. -

Xerox University Microfilms 300 North Zaab Road Ann Arbor, Michigan 46106 I I

INFORMATION TO USERS This material was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. Thefollowing explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page ($)''. If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. Whan an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that die photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You w ill find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections w ith a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

Specialist Collectors' Sale , Tue, 13 July 2021 9:00

Specialist Collectors' Sale , Tue, 13 July 2021 9:00 1 9ct gold charm bracelet with various novelty gold 17 Victorian silver vase of tapered cylindrical form and yellow metal charms £180-220 with embossed and pierced decoration on 2 9ct yellow and white gold bracelet with five white circular foot (lacking glass liner), by James gold double rope twist panels and yellow gold Dixon & Sons, Sheffield 1896. 11.5cm high £60- fittings. 20cm long £150-200 100 3 9ct gold circular open work ‘Ruth’ pendant on 18 Silver cigarette case with engine turned 9ct gold curb link chain. £250-300 decoration. Birmingham 1956 £60-100 4 Yellow and white metal Star of David pendant on 19 Victorian silver cased pocket watch with white 9ct gold chain £200-300 enamel dial, Roman numeral markers and subsidiary seconds dial, on silver watch chain 5 9ct gold Jewish heart shaped pendant on 18ct £40-60 gold chain £120-180 20 9ct gold flat curb link chain, 45.5cm long £150- 6 18ct gold diamond set black onyx plaque ring, 200 size L and 18ct gold signet ring, size R £80-120 21 9ct gold ball and fancy link chain, 59.5cm long 7 14ct gold wedding ring (stamped 585). Size Q £120-180 £40-60 22 Pair 9ct gold cufflinks, each oval panel engraved 8 9ct gold opal and ruby cluster ring, size N and with B and G £60-100 9ct gold emerald and opal flower head ring, size L½ £40-60 23 9ct gold heart pendant on 9ct gold chain, one other 9ct gold chain and 9ct gold watch bracelet 9 Two ladies' 9ct gold vintage wristwatches - parts £200-300 Accurist and Centaur, both on 9ct gold bracelets -

DRAWING and PAINTING FINAL PROJECT Mrs. J. Spadaro DUE MAY 11, 2016

DRAWING AND PAINTING FINAL PROJECT Mrs. J. Spadaro DUE MAY 11, 2016 Select an Art Movement: Classical Realism, Impressionism, Post Impressionism, Fauvism Select a Topic: A STILL LIFE FEATURING A COLLECTION OF OBJECTS: Choose ONE: 1. Sweet treats - candies, desserts, fruits – arranged in an interesting composition or looked upon from an unusual point of view 2. Natural objects – shells, pinecones, plant materials, etc arranged in an interesting composition OR A SELF PORTRAIT featuring yourself on an interesting background – a map that can showcase your heritage, the place you live now or a place that holds a special meaning to you; sheet music of a favorite song; newspaper with a meaningful article, etc. OR A well developed LANDSCAPE showcasing a particular season and including an interesting foreground, middle ground and background – no sunsets, simple beach scenes Refer to your text for reference… Pay close attention to your total work: drawing, composition, design elements, technique and color usage if applicable… remember, it is your final exam and will be graded as such. YOU MAY NOT WORK FROM PHOTOS UNLESS THEY ARE YOUR OWN REFERENCE. Draw or paint your subject influenced by the styles and artists in your selected movement. You may focus on one or more artists within that movement. Decide how you will treat color – achromatic or chromatic – perhaps a monochromatic study, or a color triad, perhaps neutral colors with the addition of one color, etc. Minimum size is 11” x 14 “ but keep your work stock size so that matting and framing is easy. THESE DRAWINGS MUST BE FULLY DEVELOPED, COMPLETED WORKS OF ART – not just quick sketches. -

Glitter Text

All That Glitters – Spark and Dazzle from the Permananent Collection co-curated by Janine LeBlanc and Roger Manley Randy and Susan Woodson Gallery January 23 – July 12, 2020 Through the ages, every human society has demonstrated a fascination with shiny objects. Necklaces made of glossy marine snail shells have been dated back nearly 135,000 years, while shiny crystals have been found in prehistoric burials, suggesting the allure they once held for their original owners. The pageantry of nearly every religion has long been enhanced by dazzling displays, from the gilded statues of Buddhist temples and the gleaming mosaics of Muslim mosques and Byzantine churches, to the bejeweled altarpieces and reliquaries of Gothic cathedrals. As both kings and gods, Hawaiian and Andean royalty alike donned garments entirely covered with brilliant feathers to proclaim their significance, while their counterparts in other cultures wore crowns of gold and gems. High status and desirability have always been signaled by the transformative effects of reflected light. Recent research indicates that our brains may be hard-wired to associate glossy surfaces with water (tinyurl.com/glossy-as-water). If so, the impulse drawing us toward them may have evolved as a survival mechanism. There may also be subconscious associations with other survival necessities. Gold has been linked to fire or the sun, the source of heat, light, and plant growth. The glitter of beads or sequins may evoke nighttime stars needed for finding one’s way. The flash of jewels may recall an instinctive association with eyes. In jungles as well as open grasslands, both prey and predator can be so well camouflaged that only the glint of an eye might reveal a lurking presence. -

The Duel Conrad, Joseph

The Duel Conrad, Joseph Published: 1908 Categorie(s): Fiction, Short Stories, War & Military Source: http://www.gutenberg.org 1 About Conrad: Joseph Conrad (born Teodor Józef Konrad Korzeniowski, 3 December 1857 – 3 August 1924) was a Polish-born novelist. Some of his works have been labelled romantic: Conrad's sup- posed "romanticism" is heavily imbued with irony and a fine sense of man's capacity for self-deception. Many critics regard Conrad as an important forerunner of Modernist literature. Conrad's narrative style and anti-heroic characters have influ- enced many writers, including Ernest Hemingway, D.H. Lawrence, Graham Greene, Joseph Heller and Jerzy Kosiński, as well as inspiring such films as Apocalypse Now (which was drawn from Conrad's Heart of Darkness). Source: Wikipedia Also available on Feedbooks for Conrad: • Heart of Darkness (1902) • Lord Jim (1900) • The Secret Agent (1907) • A Personal Record (1912) • Nostromo: A Tale of the Seaboard (1904) • The Nigger of the 'Narcissus' (1897) • An Outpost of Progress (1896) • The Lagoon (1897) • The Informer (1906) • Under Western Eyes (1911) Copyright: This work is available for countries where copy- right is Life+70 and in the USA. Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks http://www.feedbooks.com Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes. 2 Chapter 1 Napoleon I., whose career had the quality of a duel against the whole of Europe, disliked duelling between the officers of his army. The great military emperor was not a swashbuckler, and had little respect for tradition. Nevertheless, a story of duelling, which became a legend in the army, runs through the epic of imperial wars. -

The Poet Takes Himself Apart on Stage: Vladimir Mayakovsky's

The Poet Takes Himself Apart on Stage: Vladimir Mayakovsky’s Poetic Personae in Vladimir Mayakovsky: Tragediia and Misteriia-buff By Jasmine Trinks Senior Honors Thesis Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill March 2015 Approved: ____________________________ Kevin Reese, Thesis Advisor Radislav Lapushin, Reader CONTENTS INTRODUCTION………………………………………………1 CHAPTER I: Mayakovsky’s Superfluous Sacrifice: The Poetic Persona in Vladimir Mayakovsky: Tragediia………………….....4 CHAPTER II: The Poet-Prophet Confronts the Collective: The Poetic Persona in Two Versions of Misteriia-buff………………25 CONCLUSION…………………………………………………47 BIBLIOGRAPHY………………………………………………50 ii INTRODUCTION In his biography of Vladimir Mayakovsky, Edward J. Brown describes the poet’s body of work as a “regular alternation of lyric with political or historical themes,” noting that Mayakovsky’s long lyric poems, like Человек [Man, 1916] and Про это [About That, 1923] are followed by the propagandistic Мистерия-буфф [Mystery-Bouffe, 1918] and Владимир Ильич Ленин [Vladimir Il’ich Lenin, 1924], respectively (Brown 109). While Brown’s assessment of Mayakovsky’s work is correct in general, it does not allow for adequate consideration of the development of his poetic persona over the course of his career, which is difficult to pinpoint, due in part to the complex interplay of the lyrical and historical in his poetry. In order to investigate the problem of Mayakovsky’s ever-changing and contradictory poetic persona, I have chosen to examine two of his plays: Владимир Маяковский: Трагедия [Vladimir Mayakovsky: A Tragedy, 1913] and both the 1918 and 1921 versions of Mystery- Bouffe. My decision to focus on Mayakovsky's plays arose from my desire to examine what I termed the “spectacle-ization” of the poet’s ego—that is, the representation of the poetic persona in a physical form alive and on stage. -

F2D for This Year

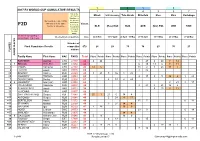

1 1 1 1 2017 F2 WORLD CUP CUMULATIVE RESULTS 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Not on the FAI Licence Minsk St Petersburg Tula Alexin Bitterfeld Kiev Kiev Karlskoga Database, or Not counted - lesser of the the Licence has expired two scores in the same Venue: F2D for this year. country or time zone. Results not BLR (Rus) KAZ RUS GER (Ukr) POL UKR SWE included in the total points. Tie broken by counting 4 24 scheduled competitions Date: 24-26 Feb 14-17 April 28 April - 01 May 29-30 April 18-19 May 20-21 May 27-28 May competitions. Top 3 only. Number of Final Cumulative Results competitor 678 24 29 76 34 23 35 23 entries: PLACED JUNIOR PLACED Family Name First Name NAC FAI ID Total Place Points Place Points Place Points Place Points Place Points Place Points Place Points 1 RASTENIS Audrius LTU 27189 84 2 24 1 28 2 24 7 14 2 1 REDIUK Illia (Jnr) UKR 84050 84 6 15 13 6 7 14 3 CYZAS Vaclovas LTU 27188 80 13 5 18 2 1 28 13 7 4 LUTSYK Andrii UKR 99795 69 2 24 =5 BELIAEV Andrey RUS 22468 65 3 21 5 16 1 28 =5 CHORNYY Stanislav UKR 84048 65 4 17 8 11 16 2 1 28 7 DUSCHENKO Dmitry RUS 22505 61 6 13 2 24 8 2 CHORNYY Ivan (Jnr) UKR 84058 60 3 21 4 17 9 CULACHKIN Stanislav ROU 94098 59 3 21 3 21 16 2 10 STEBNYTSKYI Andrii UKR 84051 54 5 15 9 11 11 YUVENKO Vasyl UKR 91957 52 12 SHTERBATHENKO Sergey BUL 72048 49 20 1 21 0 14 4 =13 ANTONOV Sergey RUS 21644 48 2 24 4 17 =13 BERTELSEN André DEN 17272 48 11 7 6 14 =13 EPISHKIN Mikhail RUS 22493 48 3 21 14 4 16 MAZURIN Igor BLR 85432 47 1 28 36 0 =17 NORD Lennart SWE 24753 44 23 0 6 14 =17 SHALAEV Aleksander RUS 21905 44 14 4 -

Title: Joseph Conrad's a Personal Record: an Anti-Confessional Autobiography

Title: Joseph Conrad's A Personal Record: An Anti-confessional Autobiography Author: Agnieszka Adamowicz-Pośpiech Citation style: Adamowicz-Pośpiech Agnieszka. (2008). Joseph Conrad's A Personal Record: An Anti-confessional Autobiography. W: W. Kalaga, M. Kubisz, J. Mydla (eds.), "Repetition and recycling in literary and cultural dialogues" (S. 87-98). Częstochowa: Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Lingwistycznej. Agnieszka Adamowicz-Pośpiech University of Silesia JOSEPH CONRAD’S A PERSONAL RECORD'. AN ANTI-CONFESSIONAL AUTOBIOGRAPHY? Joseph Conrad, as a well-known novelist, commencing to pen reminis cences about the beginnings of his nautical career and his first steps as an English writer, faced an essential dilemma.1 On one hand, the need to order and make meaningful the decisions and events from his past was so com pelling that it urged the writer to create his memoirs; on the other, Conrad’s distrust of direct confession, unequivocal externalization of his intimate “self’ made him choose the literary form of loose remembrances based on apparently chaotic associations referring to people and events from the past. The result was a collection of seemingly disconnected vignettes portraying different episodes from the author’s days of yore. The aim of this paper is firstly, to establish to what extent Conrad’s volume, A Personal Record, is an autobiography, secondly, to consider whether it is possible to create an anti confessional autobiography, and last but not least, to disclose the techniques that Conrad uses to reduce the confessional