Post-Conflict Belfast ‘Sliced and Diced’: the Case of the Gaeltacht Quarter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glas Le Fás 2 Glas Le Fás 3

GLAS LE FÁS 2 GLAS LE FÁS 3 EALAÍN CHLÚDAIGH COVER ART: AODÁN MONAGHAN 4 GLAS LE FÁS 5 Cruthaíonn Áras na bhFál an spreagadh do chomhrath. Mar gheall ar an spreagadh seo tá an gealltanas go n-athlonnófar postanna Faoin Leabhrán Seo About this booklet earnála poiblí sa Cheathrú Ghaeltachta. The Broadway Development creates a pulse for common prosperity. Tá an smaoineamh chun tosaigh go smior sa nádúr againn, ach Thinking ahead is very much part of our nature, but our With it comes the promise of the relocation of public sector jobs to the caithfidh obair s’againne díriú ar an chur i gcrích agus ar an chur i work must continue to be about implementation and Gaeltacht Quarter. bhfeidhm. Mar chaomhnóirí na Gaeilge agus an chultúir delivery. As custodians of the Irish Language and Ghaelaigh, caithfidh muid fosta bheith freagrach as na culture we must also account for the resources we use hacmhainní a úsáideann muid tríd an tairbhe do agus an tionchar by demonstrating clear community benefit and positive dhearfach shoiléir ar an phobal dá bharr a léiriú. Ach tá sin ina impact. But that is an equal challenge across chomhdhúshlán trasna an rialtais. Caithfidh an rialtais cruthú, Government. In allocating its resources it must agus é ag dáileadh acmhainní go bhfuil sé á dhéanamh le demonstrate equity in a manner that facilitates comhionannas a léiriú agus ar bhealach a ligeann do gach pobal achievement in all our communities. The Gaeltacht an chuid is fearr a bhaint amach ina áit féin. Is í triail litmis na Quarter is a litmus test of that commitment coimitminte seo ná an Cheathrú Ghaeltachta. -

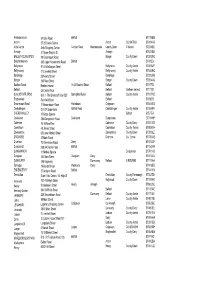

Copy of Nipx List 16 Nov 07

Andersonstown 57 Glen Road Belfast BT11 8BB Antrim 27-28 Castle Centre Antrim CO ANTRIM BT41 4AR Ards Centre Ards Shopping Centre Circular Road Newtownards County Down N Ireland BT23 4EU Armagh 31 Upper English St. Armagh BT61 7BA BALLEYHOLME SPSO 99 Groomsport Road Bangor County Down BT20 5NG Ballyhackamore 342 Upper Newtonards Road Belfast BT4 3EX Ballymena 51-63 Wellington Street Ballymena County Antrim BT43 6JP Ballymoney 11 Linenhall Street Ballymoney County Antrim BT53 6RQ Banbridge 26 Newry Street Banbridge BT32 3HB Bangor 143 Main Street Bangor County Down BT20 4AQ Bedford Street Bedford House 16-22 Bedford Street Belfast BT2 7FD Belfast 25 Castle Place Belfast Northern Ireland BT1 1BB BLACKSTAFF SPSO Unit 1- The Blackstaff Stop 520 Springfield Road Belfast County Antrim BT12 7AE Brackenvale Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 8EU Brownstown Road 11 Brownstown Road Portadown Craigavon BT62 4EB Carrickfergus CO-OP Superstore Belfast Road Carrickfergus County Antrim BT38 8PH CHERRYVALLEY 15 Kings Square Belfast BT5 7EA Coalisland 28A Dungannon Road Coalisland Dungannon BT71 4HP Coleraine 16-18 New Row Coleraine County Derry BT52 1RX Cookstown 49 James Street Cookstown County Tyrone BT80 8XH Downpatrick 65 Lower Market Street Downpatrick County Down BT30 6LZ DROMORE 37 Main Street Dromore Co. Tyrone BT78 3AE Drumhoe 73 Glenshane Raod Derry BT47 3SF Duncairn St 238-240 Antrim road Belfast BT15 2AR DUNGANNON 11 Market Square Dungannon BT70 1AB Dungiven 144 Main Street Dungiven Derry BT47 4LG DUNMURRY 148 Kingsway Dunmurray Belfast N IRELAND -

The Irish Language in Education in Northern Ireland 2Nd Edition

Irish The Irish language in education in Northern Ireland 2nd edition This document was published by Mercator-Education with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the European Commission (DG XXII: Education, Training and Youth) ISSN: 1570-1239 © Mercator-Education, 2004 The contents of this publication may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to Mercator- Education: European network for regional or minority languages and education. Mercator-Education P.O. Box 54 8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands tel. +31- 58-2131414 fax: + 31 - 58-2131409 e-mail: [email protected] website://www.mercator-education.org This regional dossier was originally compiled by Aodán Mac Póilin from Ultach Trust/Iontaobhas Ultach and Mercator Education in 1997. It has been updated by Róise Ní Bhaoill from Ultach Trust/Iontaobhas Ultach in 2004. Very helpful comments have been supplied by Dr. Lelia Murtagh, Department of Psycholinguistics, Institúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann (ITE), Dublin. Unless stated otherwise the data reflect the situation in 2003. Acknowledgment: Mo bhuíochas do mo chomhghleacaithe in Iontaobhas ULTACH, do Liz Curtis, agus do Sheán Ó Coinn, Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta as a dtacaíocht agus a gcuidiú agus mé i mbun na hoibre seo, agus don Roinn Oideachas agus an Roinn Fostaíochta agus Foghlama as an eolas a cuireadh ar fáil. Tsjerk Bottema has been responsible for the publication of the Mercator regional dossiers series from January 2004 onwards. Contents Foreword ..................................................1 1. Introduction .........................................2 2. Pre-school education .................................13 3. Primary education ...................................16 4. Secondary education .................................19 5. Further education ...................................22 6. -

Travelling with Translink

Belfast Bus Map - Metro Services Showing High Frequency Corridors within the Metro Network Monkstown Main Corridors within Metro Network 1E Roughfort Milewater 1D Mossley Monkstown (Devenish Drive) Road From every From every Drive 5-10 mins 15-30 mins Carnmoney / Fairview Ballyhenry 2C/D/E 2C/D/E/G Jordanstown 1 Antrim Road Ballyearl Road 1A/C Road 2 Shore Road Drive 1B 14/A/B/C 13/A/B/C 3 Holywood Road Travelling with 13C, 14C 1A/C 2G New Manse 2A/B 1A/C Monkstown Forthill 13/A/B Avenue 4 Upper Newtownards Rd Mossley Way Drive 13B Circular Road 5 Castlereagh Road 2C/D/E 14B 1B/C/D/G Manse 2B Carnmoney Ballyduff 6 Cregagh Road Road Road Station Hydepark Doagh Ormeau Road Road Road 7 14/A/B/C 2H 8 Malone Road 13/A/B/C Cloughfern 2A Rathfern 9 Lisburn Road Translink 13C, 14C 1G 14A Ballyhenry 10 Falls Road Road 1B/C/D Derrycoole East 2D/E/H 14/C Antrim 11 Shankill Road 13/A/B/C Northcott Institute Rathmore 12 Oldpark Road Shopping 2B Carnmoney Drive 13/C 13A 14/A/B/C Centre Road A guide to using passenger transport in Northern Ireland 1B/C Doagh Sandyknowes 1A 16 Other Routes 1D Road 2C Antrim Terminus P Park & Ride 13 City Express 1E Road Glengormley 2E/H 1F 1B/C/F/G 13/A/B y Single direction routes indicated by arrows 13C, 14C M2 Motorway 1E/J 2A/B a w Church Braden r Inbound Outbound Circular Route o Road Park t o Mallusk Bellevue 2D M 1J 14/A/B Industrial M2 Estate Royal Abbey- M5 Mo 1F Mail 1E/J torwcentre 64 Belfast Zoo 2A/B 2B 14/A/C Blackrock Hightown a 2B/D Square y 64 Arthur 13C Belfast Castle Road 12C Whitewell 13/A/B 2B/C/D/E/G/H -

Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space

2011 Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Belfast Interface Project 2011 Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space First published November 2011 Belfast Interface Project Third Floor 109-113 Royal Avenue Belfast BT1 1FF Tel: +44 (0)28 9024 2828 Email: [email protected] Web: www.belfastinterfaceproject.org ISBN: 0-9548819-2-3 Cover image: Jenny Young 2011 Maps reproduced with permission of Land & Property Services under permit number 110101. Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Contents page Acknowledgements Preface Abbreviations Introduction Section 1: Overview of Defensive Architecture Categories and Locations of Barriers: Clusters Ownership Date of Construction Blighted Space Changes Since Last Classification Section 2: Listing of Identified Structures and Spaces Cluster 1: Suffolk - Lenadoon Cluster 2: Upper Springfield Road Cluster 3: Falls - Shankill Cluster 4: The Village - Westlink Cluster 5: Inner Ring Cluster 6: Duncairn Gardens Cluster 7: Limestone Road - Alexandra Park Cluster 8: Lower Oldpark - Manor Street Cluster 9: Crumlin Road - Ardoyne - Glenbryn Cluster 10: Ligoniel Cluster 11: Whitewell Road - Longlands Cluster 12: Short Strand - Inner East Cluster 13: Ormeau Road and the Markets 5 Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the support of Belfast Community Safety partnership / Belfast City Council / Good relations Unit, the Community Relations Council, and the Northern Ireland Housing Executive in funding the production of this publication. We also thank Neil Jarman at the Institute for Conflict Research for carrying out the research and writing a report on their key findings, and note our gratitude to Jenny Young for helping to draft and edit the final document. -

CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach Agus an Rùnaire No A' Bhan- Ritnaire Aige, a Dhol Limcheall Air an Roinn I R ^ » Eòrpa Air Sgath Nan Cànain Bheaga

No. 105 Spring 1999 £2.00 • Gaelic in the Scottish Parliament • Diwan Pressing on • The Challenge of the Assembly for Wales • League Secretary General in South Armagh • Matearn? Drew Manmn Hedna? • Building Inter-Celtic Links - An Opportunity through Sport for Mannin ALBA: C O M U N N B r e i z h CEILTEACH • BREIZH: KEVRE KELTIEK • CYMRU: UNDEB CELTAIDD • EIRE: CONRADH CEILTEACH • KERNOW: KESUNYANS KELTEK • MANNIN: CEÜCIC LEAGUE COMMEEYS CELTIAGH Danmhairceach agus an rùnaire no a' bhan- ritnaire aige, a dhol limcheall air an Roinn i r ^ » Eòrpa air sgath nan cànain bheaga... Chunnaic sibh iomadh uair agus bha sibh scachd sgith dhen Phàrlamaid agus cr 1 3 a sliopadh sibh a-mach gu aighcaraeh air lorg obair sna cuirtean-lagha. Chan eil neach i____ ____ ii nas freagarraiche na sibh p-fhèin feadh Dainmheag uile gu leir! “Ach an aontaich luchd na Pàrlamaid?” “Aontaichidh iad, gun teagamh... nach Hans Skaggemk, do chord iad an òraid agaibh mu cor na cànain againn ann an Schleswig-Holstein! Abair gun robh Hans lan de Ball Vàidaojaid dh’aoibhneas. Dhèanadh a dhicheall air sgath nan cànain beaga san Roinn Eòrpa direach mar a rinn e airson na Daineis ann atha airchoireiginn, fhuair Rinn Skagerrak a dhicheall a an Schieswig-I lolstein! Skaggerak ]¡l¡r ori dio-uglm ami an mhinicheadh nach robh e ach na neo-ncach “Ach tha an obair seo ro chunnartach," LSchlesvvig-Molstein. De thuirt e sa Phàrlamaid. Ach cha do thuig a cho- arsa bodach na Pàrlamaid gu trom- innte ach:- ogha idir. chridheach. “Posda?” arsa esan. -

Irish Medium.Indd

PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Review of IRISH-MEDIUM EDUCATION REPORT ReviewReview ofof Irish-mediumIrish-medium EducationEducation ReportReport PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES Ministerial Foreword PHOTO REDACTED DUE TO THIRD PARTY RIGHTS OR OTHER LEGAL ISSUES I want to welcome this Review from the Irish-medium Review Board, and acknowledge the on-going work of the Irish-medium sector in the north of Ireland. The Irish Language sector is a bold, dynamic and thriving one; the Irish Education sector is a key component of that sector. In terms of the consultation, it must share that same vision, that same dynamism. All stakeholders, enthusiasts and educationalists from across Ireland have a key role to play in this consultation and I encourage them to contribute to the Review. The Irish language is an integral component of our rich and shared heritage; as a sector it is thriving, educationally, socially and economically. More than ever students passing through the Irish Education sector have the opportunity to continue their education, set up home and choose a career all through the medium of Irish. Organisations across the Island, such as TG4, Ráidió Fáilte, and Forbairt Feirste are thriving and offering very real opportunities for growth and employment to students within the Irish-medium sector. The public sector, and other bodies such as Foras na Gaeilge and the GAA, work in many areas to develop employment and participation opportunities for increasing numbers of people. i Review of Irish-medium Education Report Gaelscoileanna are producing confi dent, capable, productive, dynamic and bi-lingual students every year and this is a wonderful contribution to our society. -

Licences Issued Under Delegated Authority Date

LICENSING COMMITTEE Subject: Licences Issued Under Delegated Authority Date: 12th December, 2018 Reporting Officer: Stephen Hewitt, Building Control Manager, ext. 2435 Contact Officer: James Cunningham, Regulatory Services Manager, Ext 3375 Restricted Reports Is this report restricted? Yes No X If Yes, when will the report become unrestricted? After Committee Decision After Council Decision Some time in the future Never Call-in Is the decision eligible for Call-in? Yes No X 1.0 Purpose of Report or Summary of main Issues 1.1 Under the Scheme of Delegation, the Director of Planning and Building Control is responsible for exercising all powers in relation to the issue, but not refusal, of permits and licences, excluding provisions relating to the issue of Entertainments Licences where adverse representations have been made. Those applications which were dealt with under the Scheme are listed below. 2.0 Recommendations 2.1 The Committee is requested to note the applications that have been issued under the Scheme of Delegation. 3.0 Main report Key Issues 3.1 Under the terms of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 the following Entertainments Licences were issued since your last meeting. Type of Premises and Location Hours Licensed Applicant Application Mr Robert Davis, Alibi, 23-31 Bradbury Sun: 12.30 - 01.00 Renewal Regency Hotel Place, Belfast, BT7 1RR. Mon - Sat: 11.30 - 03.00 (NI) Ltd Belfast Boat Club, Sun: 12.30 - 22.00 12 Lockview Road, Renewal Mr Andrew Gault Mon - Sat: 11.30 - 23.00 Belfast, BT9 5FJ. City Hall, Donegall Belfast City Square, Renewal Sun - Sat: 08.00 - 01.00 Council Belfast, BT1 5GS. -

Entering Catholic West Belfast

Chapter 1 A Walk of Life Entering Catholic West Belfast n a Friday afternoon in September 2004, shortly before returning home from Omy ethnographic fieldwork, I took my video camera and filmed a walk from the city centre into Catholic West Belfast up to the Beechmount area, where I had lived and conducted much of my research. I had come to Catholic West Belfast fourteen months prior with the intention of learning about locally prevailing senses of ethnic identity. Yet I soon found out that virtually every local Catholic I talked to seemed to see him- or herself as ‘Irish’, and apparently expected other locals to do the same. My open questions such as ‘What ethnic or national identity do you have?’ at times even irritated my interlocutors, not so much, as I figured out, because they felt like I was contesting their sense of identity but, to the contrary, because the answer ‘Irish’ seemed so obvious. ‘What else could I be?’ was a rhetorical question I often encountered in such conversations, indicating to me that, for many, Irish identity went without saying. If that was the case, then what did being Irish mean to these people? What made somebody Irish, and where were local senses of Irishness to be found? Questions like these became the focus of my investigations and constitute the overall subject of this book. One obvious entry point for addressing such questions consisted in attending to the ways in which Irishness was locally represented. Listening to how locals talked about their Irishness, keeping an eye on public representations by organizations and the media, and explicitly asking people about their Irishness in informal conversations and formal interviews all constituted ways of approaching this topic. -

DPS028 Urban Capacity Study

DPS028 Belfast City Council Urban Capacity Study Final | 20 March 2018 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 255403-00 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd Bedford House 3rd Floor 16-22 Bedford Street Belfast BT2 7FD Northern Ireland www.arup.com Document Verification Job title Urban Capacity Study Job number 255403-00 Document title File reference Document ref Revision Date Filename Methodology Report 1st Draft.docx Draft 1 29 May Description First draft for discussion on 21.06.2017 2017 Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Kieran Carlin Wayne Dyer Wayne Dyer Signature Draft 2 27.10.20 Filename Urban Capacity Study 1st Draft 17 Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Kieran Carlin Signature Draft 3 04.12.20 Filename Revised following detailed comments from BCC 17 Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Kieran Carlin Signature Filename Description Prepared by Checked by Approved by Name Signature Issue Document Verification with Document | Final | 20 March 2018 \\GLOBAL\EUROPE\BELFAST\JOBS\255000\255403-00\4_INTERNAL_PROJECT_DATA\4-50_REPORTS\BELFAST UCS FINAL\FINAL VERSION ISSUED 19.04.2018\URBAN CAPACITY STUDY FINAL REPORT V5 20.03.2018.DOCX Belfast City Council Urban Capacity Study DPS028 Contents Page Introduction 6 Policy Context 6 2.1 The Regional Development Strategy 2035 7 2.2 Strategic Planning Policy Statement (SPPS) 8 2.3 -

POP022 Topic Paper: Transportation

POP022 Belfast LOCAL DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2020-2035 Transportation Topic Paper December 2016 Executive Summary Context A good transportation system helps people get to where they need to go quickly and easily and makes our towns and cities better places to live. In Northern Ireland, there is a history of heavy reliance on the private car as a means of travel. However, in recent years Belfast has witnessed many improvements in the city’s transportation system, in terms of roads, public transport and walking and cycling. As Belfast continues to grow and modernise, continued developments and major enhancements to our transport infrastructure are still required. The need to integrate transportation and land use to maximise development around quality sustainable transport networks is an essential element of the local development plan. The responsibility for transport policies and initiatives lies with the Department for Infrastructure (DfI) (formerly Department for Regional Development (DRD)). During the plan-making process the Council will be required to work closely with DfI to incorporate transport policy and initiatives into the Plan. The Local Development Plan (LDP) will need to be consistent with the objectives of the Regional Development Strategy (RDS) 2035 and relevant Transport Plans. Regional guidance outlines the need to deliver a balanced approach to transport infrastructure, support the growth of the economy, enhance quality of life for all and reduce the environmental impact of transport. POP022 Evidence base Social, Economic & Environmental -

La04/2019/0218/F

Development Management Report Committee Application Summary Committee Meeting Date: Tuesday 17 September 2019 Application ID: LA04/2019/0218/F Proposal: Location: Environmental and ecological improvements Springfield Dam and Park works comprising upgrades to existing Springfield Road entrances, provision of a new entrance, Belfast rearrangement of existing car parking, BT12 7DN enhancements to existing paths including a proposed circular pathway and landscaping. Installation of a causeway bridge, modular classroom, fishing stands, floating habitat islands, fencing, lighting and additional street furniture. Referral Route: Major Application Recommendation: Approval Applicant Name and Address: Agent Name and Address: Belfast City Council Richard Martin 9 Adelaide Street 2 Clarence Street West Belfast Belfast Executive Summary: The application seeks full permission for the environmental and ecological improvements works within Springfield Park and Dam comprising upgrades to existing entrances, provision of a new entrance, rearrangement of existing car parking, enhancements to existing paths including a proposed circular pathway and landscaping. Installation of a causeway bridge, modular classroom, fishing stands, floating habitat islands, fencing, lighting and additional street furniture. The key issues are: - principle of use on the site - design and layout - impact on natural heritage - access, movement, parking and transportation, including road safety - impact on built heritage - flood risk - landscaping - other environmental matters The site displays a dam, green spaces, pathways with large mature trees. The site is within a local landscape policy area (LLPA), Springfield Park and Dam, BT 134, and site of local nature conservation importance (SLNCI), Springfield Pond BT 084/26, as designated within (Draft) Belfast Metropolitan Area Plan (BMAP) 2015. The site is unzoned within the Belfast Urban Area Plan 2001 (BUAP).