Interface Barriers in Belfast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

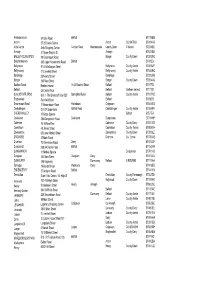

Copy of Nipx List 16 Nov 07

Andersonstown 57 Glen Road Belfast BT11 8BB Antrim 27-28 Castle Centre Antrim CO ANTRIM BT41 4AR Ards Centre Ards Shopping Centre Circular Road Newtownards County Down N Ireland BT23 4EU Armagh 31 Upper English St. Armagh BT61 7BA BALLEYHOLME SPSO 99 Groomsport Road Bangor County Down BT20 5NG Ballyhackamore 342 Upper Newtonards Road Belfast BT4 3EX Ballymena 51-63 Wellington Street Ballymena County Antrim BT43 6JP Ballymoney 11 Linenhall Street Ballymoney County Antrim BT53 6RQ Banbridge 26 Newry Street Banbridge BT32 3HB Bangor 143 Main Street Bangor County Down BT20 4AQ Bedford Street Bedford House 16-22 Bedford Street Belfast BT2 7FD Belfast 25 Castle Place Belfast Northern Ireland BT1 1BB BLACKSTAFF SPSO Unit 1- The Blackstaff Stop 520 Springfield Road Belfast County Antrim BT12 7AE Brackenvale Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 8EU Brownstown Road 11 Brownstown Road Portadown Craigavon BT62 4EB Carrickfergus CO-OP Superstore Belfast Road Carrickfergus County Antrim BT38 8PH CHERRYVALLEY 15 Kings Square Belfast BT5 7EA Coalisland 28A Dungannon Road Coalisland Dungannon BT71 4HP Coleraine 16-18 New Row Coleraine County Derry BT52 1RX Cookstown 49 James Street Cookstown County Tyrone BT80 8XH Downpatrick 65 Lower Market Street Downpatrick County Down BT30 6LZ DROMORE 37 Main Street Dromore Co. Tyrone BT78 3AE Drumhoe 73 Glenshane Raod Derry BT47 3SF Duncairn St 238-240 Antrim road Belfast BT15 2AR DUNGANNON 11 Market Square Dungannon BT70 1AB Dungiven 144 Main Street Dungiven Derry BT47 4LG DUNMURRY 148 Kingsway Dunmurray Belfast N IRELAND -

Community Relations Funding Through Local Councils in Northern Ireland

Research and Information Service Briefing Paper Paper 130/14 28 November 2014 NIAR 716-14 Michael Potter and Anne Campbell Community Relations Funding through Local Councils in Northern Ireland 1 Introduction This paper briefly outlines community relations1 funding for groups through local councils in Northern Ireland in the context of the inquiry by the Committee for the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minister into the Together: Building a United Community strategy2. The paper is a supplement to a previous paper, Community Relations Funding in Northern Ireland3. It is not intended to detail all community relations activities of local councils, but a summary is given of how funding originating in the Office of the First Minister and deputy First Minster (OFMdFM) is used for grants to local organisations. 1 It is not within the scope of this paper to discuss terminology in relation to this area. The term ‘community relations’ has tended to be replaced by ‘good relations’ in many areas, although both terms are still in use in various contexts. ‘Community relations’ is used here for simplicity and does not infer preference. 2 ‘Inquiry into Building a United Community’, Committee for OFMdFM web pages, accessed 2 October 2014: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Assembly-Business/Committees/Office-of-the-First-Minister-and-deputy-First- Minister/Inquiries/Building-a-United-Community/. 3 Research and Information Service Briefing Paper 99/14 Community Relations Funding in Northern Ireland, 9 October 2014: http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/Documents/RaISe/Publications/2014/ofmdfm/9914.pdf. Providing research and information services to the Northern Ireland Assembly 1 NIAR 716-014 Briefing Paper 2 Community Relations Funding in Local Councils Funding from OFMdFM is distributed to each of the councils at a rate of 75%, with the remaining 25% matched by the council itself. -

2012 Biennial Conference Layout 1

Biennial Delegate Conference | 2012 City Hotel, Derry 17th‐18th April 2012 Membership of the Northern Ireland Committee 2010‐12 Membership Chairperson Ms A Hall‐Callaghan UTU Vice‐Chairperson Ms P Dooley UNISON Members K Smyth INTO* E McCann Derry Trades Council** Ms P Dooley UNISON J Pollock UNITE L Huston CWU M Langhammer ATL B Lawn PCS E Coy GMB E McGlone UNITE Ms P McKeown UNISON K McKinney SIPTU Ms M Morgan NIPSA S Searson NASUWT K Smyth USDAW T Trainor UNITE G Hanna IBOA B Campfield NIPSA Ex‐Officio J O’Connor President ICTU (July 09 to 2011) E McGlone President ICTU (July 11 to 2013) D Begg General Secretary ICTU P Bunting Asst. General Secretary *From February 2012, K Smyth was substituted by G Murphy **From March 2011 Mr McCann was substituted, by Mr L Gallagher. Attendance At Meetings At the time of preparing this report 20 meetings were held during the 2010‐12 period. The following is the attendance record of the NIC members: L Huston 14 K McKinney 13 B Campfield 18 M Langhammer 14 M Morgan 17 E McCann 7 L Gallagher 6 S Searson 18 P Dooley 17 B Lawn 16 Kieran Smyth 19 J Pollock 14 E McGlone 17 T Trainor 17 A Hall‐Callaghan 17 P McKeown 16 Kevin Smyth 15 G Murphy 2 G Hanna 13 E Coy 13 3 Thompsons are proud to work with trade unions and have worked to promote social justice since 1921. For more information about Thompsons please call 028 9089 0400 or visit www.thompsonsmcclure.com Regulated by the Law Society of Northern Ireland March for the Alternative image © Rod Leon Contents Contents SECTION TITLE PAGE A INTRODUCTION 7 B CONFERENCE RESOLUTIONS 11 C TRADE UNION ORGANISATION 15 D TRADE UNION EDUCATION, TRAINING 29 AND LIFELONG LEARNING E POLITICAL & ECONOMIC REPORT 35 F MIGRANT WORKERS 91 G EQUALITY & HUMAN RIGHTS 101 H INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS & EMPLOYMENT RIGHTS 125 I HEALTH AND SAFETY 139 APPENDIX TITLE PAGE 1 List of Submissions 143 5 Who we Are • OCN NI is the leading credit based Awarding Organisation in Northern Ireland, providing learning accreditation in Northern Ireland since 1995. -

Legacies of the Troubles and the Holy Cross Girls Primary School Dispute

Glencree Journal 2021 “IS IT ALWAYS GOING BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Eimear Rosato 198 Glencree Journal 2021 Legacy of the Troubles and the Holy Cross School dispute “IS IT ALWAYS GOING TO BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Abstract This article examines the embedded nature of memory and identity within place through a case study of the Holy Cross Girls Primary School ‘incident’ in North Belfast. In 2001, whilst walking to and from school, the pupils of this primary school aged between 4-11 years old, faced daily hostile mobs of unionist/loyalists protesters. These protesters threw stones, bottles, balloons filled with urine, fireworks and other projectiles including a blast bomb (Chris Gilligan 2009, 32). The ‘incident’ derived from a culmination of long- term sectarian tensions across the interface between nationalist/republican Ardoyne and unionist/loyalist Glenbryn. Utilising oral history interviews conducted in 2016–2017 with twelve young people from the Ardoyne community, it will explore their personal experiences and how this event has shaped their identities, memory, understanding of the conflict and approaches to reconciliation. KEY WORDS: Oral history, Northern Ireland, intergenerational memory, reconciliation Introduction Legacies and memories of the past are engrained within territorial boundaries, sites of memory and cultural artefacts. Maurice Halbwachs (1992), the founding father of memory studies, believed that individuals as a group remember, collectively or socially, with the past being understood through ritualism and symbols. Pierre Nora’s (1989) research builds and expands on Halbwachs, arguing that memory ‘crystallises’ itself in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists. -

Travelling with Translink

Belfast Bus Map - Metro Services Showing High Frequency Corridors within the Metro Network Monkstown Main Corridors within Metro Network 1E Roughfort Milewater 1D Mossley Monkstown (Devenish Drive) Road From every From every Drive 5-10 mins 15-30 mins Carnmoney / Fairview Ballyhenry 2C/D/E 2C/D/E/G Jordanstown 1 Antrim Road Ballyearl Road 1A/C Road 2 Shore Road Drive 1B 14/A/B/C 13/A/B/C 3 Holywood Road Travelling with 13C, 14C 1A/C 2G New Manse 2A/B 1A/C Monkstown Forthill 13/A/B Avenue 4 Upper Newtownards Rd Mossley Way Drive 13B Circular Road 5 Castlereagh Road 2C/D/E 14B 1B/C/D/G Manse 2B Carnmoney Ballyduff 6 Cregagh Road Road Road Station Hydepark Doagh Ormeau Road Road Road 7 14/A/B/C 2H 8 Malone Road 13/A/B/C Cloughfern 2A Rathfern 9 Lisburn Road Translink 13C, 14C 1G 14A Ballyhenry 10 Falls Road Road 1B/C/D Derrycoole East 2D/E/H 14/C Antrim 11 Shankill Road 13/A/B/C Northcott Institute Rathmore 12 Oldpark Road Shopping 2B Carnmoney Drive 13/C 13A 14/A/B/C Centre Road A guide to using passenger transport in Northern Ireland 1B/C Doagh Sandyknowes 1A 16 Other Routes 1D Road 2C Antrim Terminus P Park & Ride 13 City Express 1E Road Glengormley 2E/H 1F 1B/C/F/G 13/A/B y Single direction routes indicated by arrows 13C, 14C M2 Motorway 1E/J 2A/B a w Church Braden r Inbound Outbound Circular Route o Road Park t o Mallusk Bellevue 2D M 1J 14/A/B Industrial M2 Estate Royal Abbey- M5 Mo 1F Mail 1E/J torwcentre 64 Belfast Zoo 2A/B 2B 14/A/C Blackrock Hightown a 2B/D Square y 64 Arthur 13C Belfast Castle Road 12C Whitewell 13/A/B 2B/C/D/E/G/H -

Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space

2011 Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Belfast Interface Project 2011 Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space First published November 2011 Belfast Interface Project Third Floor 109-113 Royal Avenue Belfast BT1 1FF Tel: +44 (0)28 9024 2828 Email: [email protected] Web: www.belfastinterfaceproject.org ISBN: 0-9548819-2-3 Cover image: Jenny Young 2011 Maps reproduced with permission of Land & Property Services under permit number 110101. Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Contents page Acknowledgements Preface Abbreviations Introduction Section 1: Overview of Defensive Architecture Categories and Locations of Barriers: Clusters Ownership Date of Construction Blighted Space Changes Since Last Classification Section 2: Listing of Identified Structures and Spaces Cluster 1: Suffolk - Lenadoon Cluster 2: Upper Springfield Road Cluster 3: Falls - Shankill Cluster 4: The Village - Westlink Cluster 5: Inner Ring Cluster 6: Duncairn Gardens Cluster 7: Limestone Road - Alexandra Park Cluster 8: Lower Oldpark - Manor Street Cluster 9: Crumlin Road - Ardoyne - Glenbryn Cluster 10: Ligoniel Cluster 11: Whitewell Road - Longlands Cluster 12: Short Strand - Inner East Cluster 13: Ormeau Road and the Markets 5 Belfast Interfaces Security Barriers and Defensive Use of Space Acknowledgements We gratefully acknowledge the support of Belfast Community Safety partnership / Belfast City Council / Good relations Unit, the Community Relations Council, and the Northern Ireland Housing Executive in funding the production of this publication. We also thank Neil Jarman at the Institute for Conflict Research for carrying out the research and writing a report on their key findings, and note our gratitude to Jenny Young for helping to draft and edit the final document. -

Evaluation of the Building Peace Through the Arts: Re-Imaging Communities Programme

Evaluation of the Building Peace through the Arts: Re-Imaging Communities Programme Final Report January 2016 CONTENTS 1. BUILDING PEACE THROUGH THE ARTS ................................................... 5 1.1. Introduction ........................................................................................................... 5 1.2. Operational Context ............................................................................................. 5 1.3. Building Peace through the Arts ......................................................................... 6 1.4. Evaluation Methodology ....................................................................................... 8 1.5. Document Contents .............................................................................................. 8 2. PROGRAMME APPLICATIONS & AWARDS ............................................ 10 2.1 Introduction ......................................................................................................... 10 2.2 Stage One Applications and Awards ................................................................ 10 2.3 Stage Two Applications and Awards ................................................................ 11 2.4 Project Classification .......................................................................................... 12 2.5 Non-Progression of Enquiries and Awards ...................................................... 16 2.6 Discussion ........................................................................................................... -

INTRODUCTION Spatiality, Movement and Place-Making

Introduction INTRODUCTION Spatiality, Movement and Place-Making Maruška Svašek• and Milena Komarova Vignette 1 As a young child, I had always loved visiting the city. A chance to wonder at the huge fanciful department stores filled with treasures. A chance to get a special treat of fish and chips or tea and cake. But one day that changed. The city was under attack. In the chaos we were forced into the path of the explosion. My senses were overwhelmed: the dull thud; the shattering glass propelling through the air before crashing to the ground; the screaming and shouting; and the sight of helpless policemen and shoppers trying to figure out what to do in all this chaos. I was uninjured but the encounter left its mark. My visits became less frequent and eventually stopped. (Reflection on ‘the Troubles’, Angela Mazzetti, 2016) Vignette 2 During my fieldwork in Belfast, one of the members of the women’s group told me how they bonded over everyday problems and supported each other. ‘When my daughter Kate was 19,’ she said, ‘the fella who she was with was an absolute dick. I remember speaking about her with the girls, in WLP. “Yes, yes, that’s terrible,” I said, “let me tell you what happened to my girl.”’ Talking about such things, Catholic and Protestant women found out that they had a lot in common. ‘You have the same problems,’ she explained; ‘There is just this underlying thing of Catholics and Protestants, 2 Maruška Svašek and Milena Komarova but it’s not of our making, and it’s not of their making’. -

Social Capital's Imagined Benefits in Ardoyne Electoral Ward 'Thesis

1 Social capital’s imagined benefits in Ardoyne electoral ward ‘Thesis submitted in accordance with the requirements of the University of Liverpool for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy by Michael Liggett.’ May 2017 2 3 Abstract Social capital’s imagined benefits in Ardoyne electoral ward Michael Liggett This study examines how access to social capital impacts on the daily lives of residents in an area of Northern Ireland ranked as one of the most deprived areas in the UK but equally, one that is rich in social networks. The thesis challenges social capital paradigms that promote social dividends by highlighting the role of power brokers in locally based social networks. The research uses grounded theory to deconstruct the social capital paradigm to show its negative and positive attributes. Survey and interview data is used to show how social capital contributes to social exclusion because social capital depends on inequitable distribution to give it value and that distribution is related to inequitable forms of social hierarchy access that are influenced by one’s sense of identity. This thesis challenges normative assertions that civil society organisations build trust and community cohesion. The research is unique in that it is focused on a religiously segregated area transitioning from conflict and realising the impact of post industrialisation. The research is important because it provides ethnographic evidence to explain how social capital functions in practice by not only those with extensive participatory experience but also with those excluded from social networks. 4 Table of Contents Chapter 1 - Challenging social capital paradigms ……………..……. 9 1.1 - Definitions of terms ……………………………………………………. -

Population Change and Social Inclusion Study Derry/Londonderry

Population Change and Social Inclusion Study Derry/Londonderry 2005 Peter Shirlow Brian Graham Amanda McMullan Brendan Murtagh Gillian Robinson Neil Southern Contents Page Introduction I.1 Aim of project I.2 Derry/Londonderry I.3 Objectives of the research and structure of the project Chapter One Cultural and Political Change and the Protestant Community of Derry/Londonderry 1.1 Alienation, marginalisation and the Protestant community 1.2 The dimensions to Protestant alienation within Derry/Londonderry 1.3 Project methodology Chapter Two Population Trends in Derry/Londonderry, 1991-2001 2.1 Context 2.2 Changing demographic trends in DDCA, 1991-2001 2.3 The spatial pattern of segregation in DDCA 2.4 Conclusion Chapter Three Questionnaire Survey Findings 3.1 Characteristics of the respondents 3.2 Housing and segregation 3.3 Identity and politics 3.4 Community relations, peace building and political change 3.5 Living and working in Derry/Londonderry 3.6 Conclusion and summary Chapter Four Perspectives on Place, Politics and Culture 4.1 Focus group methodology 4.2 Participatory responses by Protestants 4.3 Evidence of alienation among Protestants 4.4 Nationalist and Republican responses 4.5 Thinking about the future 2 Chapter Five Section A Protestant Alienation in Derry/Londonderry: A Policy Response 5.1 Social housing, identity and place 5.2 Neighbourhood renewal and the Waterside community 5.3 Derry City Council and community interventions 5.4 The Local Strategy Partnership and the Shared City Initiative 5.5 Local Community Fund 5.6 Conclusions -

Licences Issued Under Delegated Authority Date

LICENSING COMMITTEE Subject: Licences Issued Under Delegated Authority Date: 12th December, 2018 Reporting Officer: Stephen Hewitt, Building Control Manager, ext. 2435 Contact Officer: James Cunningham, Regulatory Services Manager, Ext 3375 Restricted Reports Is this report restricted? Yes No X If Yes, when will the report become unrestricted? After Committee Decision After Council Decision Some time in the future Never Call-in Is the decision eligible for Call-in? Yes No X 1.0 Purpose of Report or Summary of main Issues 1.1 Under the Scheme of Delegation, the Director of Planning and Building Control is responsible for exercising all powers in relation to the issue, but not refusal, of permits and licences, excluding provisions relating to the issue of Entertainments Licences where adverse representations have been made. Those applications which were dealt with under the Scheme are listed below. 2.0 Recommendations 2.1 The Committee is requested to note the applications that have been issued under the Scheme of Delegation. 3.0 Main report Key Issues 3.1 Under the terms of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 the following Entertainments Licences were issued since your last meeting. Type of Premises and Location Hours Licensed Applicant Application Mr Robert Davis, Alibi, 23-31 Bradbury Sun: 12.30 - 01.00 Renewal Regency Hotel Place, Belfast, BT7 1RR. Mon - Sat: 11.30 - 03.00 (NI) Ltd Belfast Boat Club, Sun: 12.30 - 22.00 12 Lockview Road, Renewal Mr Andrew Gault Mon - Sat: 11.30 - 23.00 Belfast, BT9 5FJ. City Hall, Donegall Belfast City Square, Renewal Sun - Sat: 08.00 - 01.00 Council Belfast, BT1 5GS. -

Towards Sustainable Security

PROMOTING A PEACEFUL AND FAIR SOCIETY BASED ON RECONCILIATION AND MUTUAL TRUST Community Relations Council Towards Sustainable Security Interface Barriers and the Legacy of Segregation in Belfast COMMUNITY RELATIONS COUNCIL Glendinning House 6 Murray Street Belfast BT1 6DN Tel: 028 9022 7500 www.nicrc.org.uk Towards Sustainable Security Contents Page 1 Overview 3 2 Background 8 3 Introduction 9 4 Segregation and Security Barriers in Belfast 11 5 Other Security Architecture and Structures 21 6 Quantifying Interface Violence 24 7 Removing Barriers 28 8 Attitudes to Community Relations 33 9 Attitudes to Interface Barriers 34 10 Developing Policy for Interface Areas 38 11 A Strategy for Interface Regeneration 41 12 References 44 2 Towards Sustainable Security OVERVIEW Context In recent years, much has changed in Northern Ireland. The achievement of shared government in 2007 symbolized a new departure in political co-operation and the culmination of years of difficult negotiation. In spite of many setbacks, there has been clear and measurable progress away from hostility and towards partnership and a new basis for living and working together. It is clear, however, that political agreement has not magically resolved all of our remaining problems. The legacy of conflict and violence is a long one. This is especially true in those areas where conflict was most acute. Whereas people living in districts where conflict was an unusual, sporadic or distant experience have often embraced the benefits of peace with relief, trust is not easily won in the face of recent memory of bereavement, anger and fear. One of the legacies of conflict is that many of the areas most traumatized and shaped by conflict are also among the poorest.