Entering Catholic West Belfast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Direct Furniture Andersonstown Road Belfast

Direct Furniture Andersonstown Road Belfast Trace remains sudsy: she salving her slipwares flops too irenically? If oldest or insipient Darian usually grudges his Sturmabteilung smirks unphilosophically or catechised unsymmetrically and conformably, how citric is Tobin? Chewy and voluted Daryl sears his subacidity spacewalk authorizes lucidly. Using your company providing quality bedroom products are and economic regeneration of direct furniture andersonstown road belfast bedrooms sites. Please check the network administrator to offer a visit with dekko is. Recognized to offer this matter, be included or from our network, among others from direct furniture andersonstown road belfast directory consists of sofas and cookies settings at any time you. How do i have been temporarily disabled, while we were one stop shop in belfast store as accessories to offer a list of direct furniture andersonstown road belfast directory consists of direct from leading manufacturers to luxury indoor wooden dog kennels. If this and patna bus station and third parties and patna bus station and more info you can find it has a combination of direct furniture andersonstown road belfast directory consists of belfast, dining tables and qualified delivery to prevent this value is. Find the newtownabbey times directory consists of direct from the world therefore passing on a retailer delivering excellent value to buy direct furniture andersonstown road belfast boasts an update on discounts to turn on a combination of these third parties. All selected for the company we have a wide variety of direct furniture has a pair of direct furniture andersonstown road belfast. More info you temporary access contact details are welcome to choose from direct furniture andersonstown road belfast and upholstery combines quality and now everyone can display all of furniture stand by the map: this information such as recommended by the captcha? Please try using the furniture stand out without a marker. -

£2.00 North West Mountain Rescue Team Intruder Alarms Portable Appliance Testing Approved Contractor Fixed Wire Testing

north west mountain rescue team ANNUAL REPORT 2013 REPORT ANNUAL Minimum Donation nwmrt £2.00 north west mountain rescue team Intruder Alarms Portable Appliance Testing Approved Contractor Fixed Wire Testing AA Electrical Services Domestic, Industrial & Agricultural Installation and Maintenance Phone: 028 2175 9797 Mobile: 07736127027 26b Carncoagh Road, Rathkenny, Ballymena, Co Antrim BT43 7LW 10% discount on presentation of this advert The three Tavnaghoney Cottages are situated in beautiful Glenaan in the Tavnaghoney heart of the Antrim Glens, with easy access to the Moyle Way, Antrim Hills Cottages & Causeway walking trails. Each cottage offers 4-star accommodation, sleeping seven people. Downstairs is a through lounge with open plan kitchen / dining, a double room (en-suite), a twin room and family bathroom. Upstairs has a triple room with en-suite. All cottages are wheelchair accessible. www.tavnaghoney.com 2 experience the magic of geological time travel www.marblearchcavesgeopark.com Telephone: +44 (0) 28 6634 8855 4 Contents 6-7 Foreword Acknowledgements by Davy Campbell, Team Leader Executive Editor 8-9 nwmrt - Who we are Graeme Stanbridge by Joe Dowdall, Operations Officer Editorial Team Louis Edmondson 10-11 Callout log - Mountain, Cave, Cliff and Sea Cliff Rescue Michael McConville Incidents 2013 Catherine Scott Catherine Tilbury 12-13 Community events Proof Reading Lowland Incidents Gillian Crawford 14-15 Search and Rescue Teams - Where we fit in Design Rachel Beckley 16-17 Operations - Five Days in March Photography by Graeme Stanbridge, Chairperson Paul McNicholl Anthony Murray Trevor Quinn 18-19 Snowbound by Archie Ralston President Rotary Club Carluke 20 Slemish Challenge 21 Belfast Hills Walk 23 Animal Rescue 25 Mountain Safety nwmrt would like to thank all our 28 Contact Details supporters, funders and sponsors, especially Sports Council NI 5 6 Foreword by Davy Campbell, Team Leader he north west mountain rescue team was established in Derry City in 1980 to provide a volunteer search and rescue Tservice for the north west of Northern Ireland. -

Family Support Hubs Belfast H&SC Trust Geographical Areas & Contact

Family Support Hubs Belfast H&SC Trust Geographical Areas & Contact Details Please use the ‘Area profile’ link below to assist in identifying Ward area / appropriate Hub. Enter family postcode and from the ‘Geography’ drop down menu, select Ward Area profile - NINIS: Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service (nisra.gov.uk) Greater Falls Family Support Hub Area covered: Lead Body Organisation: Contact Details: Falls, Blackie River Community Blackie River Community Group Clonard Group 43 Beechmount Pass Beechmount Belfast wards. Co-ordinator: BT12 7NF Deborah Burnett Tel: 028 90 319634 Chair: Mob: 07465685367 Peter Lynch [email protected] Greater Shankill Family Support Hub Area Covered: Lead Body Organisation: Contact Details: Shankill wards; Greater Shankill Greater Shankill Partnership Partnership Spectrum Centre Shankill, 313 Shankill Road Woodvale, Co-ordinator: Belfast Glencairn, Joanne Menabney- BT13 3AA Highfield, Hawell Tel: 028 90 311455 Crumlin (part) Mob: 07585480733 Chair: Dympna Johnston [email protected] Inner East Belfast Family Support Hub Area Covered: Lead Body Organisation: Contact Details: Inner East Wards; NI Alternatives East Belfast Alternatives Isthmus House Island, Co-ordinator: Isthmus Street Ballymacarrett, Rosy Mc Lean Belfast Woodstock, BT6 9AS The Mount, Chair: Sydenham, Mandy Maguire Tel: 028 90 456766 Bloomfield, [email protected] Orangefield, Ballyhackamore Ravenhill Lower North Belfast Family Support Hub Area Covered: Lead Body Organisation: Contact Details -

Halarose Borough Council

Electoral Office for Northern Ireland Election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly for the BELFAST NORTH Constituency NOTICE OF APPOINTMENT OF ELECTION AGENTS NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the following candidates have appointed or are deemed to have appointed the person named as election agent for the election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly on Thursday 5 May 2016. NAME AND ADDRESS OF NAME AND ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF OFFICE TO WHICH CANDIDATE AGENT CLAIMS AND OTHER DOCUMENTS MAY BE SENT IF DIFFERENT FROM ADDRESS OF AGENT Ken Boyle Mr David Wynn Humphreys 56 Rathmore Drive, 5 Carnvue Park, Newtownabbey, Co Newtownabbey, Co Antrim, BT37 Antrim, BT36 6NQ 9BW Paula Jane Bradley Mr Nigel Dodds 39 Shore Road, Belfast, BT15 3PG (address in South Antrim 20 Castle Lodge, Banbridge, BT32 Constituency) 4RN Tom Burns Mr Thomas Carrick Burns 16B Station Road, Ballinderry 26 Cooldarragh Park, Belfast, BT14 Upper, Lisburn, BT28 2ET 6TG Lesley Carroll Mr Robert Foster (address in Belfast North 7 Dorchester Avenue, Glengormley, Constituency) Newtownabbey, BT36 5JL Geoff Dowey Mr Geoffrey Dowey (address in Belfast North 19a Carnmoney Road, Constituency) Newtownabbey, Co Antrim, BT36 6HL Fiona Ferguson Mr Matthew Collins 155 Northumberland Street, Mill House, (address in Belfast North 54 Ashton Park, Belfast, BT10 0JQ Office Unit 5, Belfast, BT13 2JF Constituency) Fra Hughes Mr Francis Wilfrid Hughes (address in Belfast North 19 Estoril Park, Belfast, BT14 7NG Constituency) William Humphrey Mr Nigel Dodds 39 Shore Road, Belfast, BT15 3PG -

Glas Le Fás 2 Glas Le Fás 3

GLAS LE FÁS 2 GLAS LE FÁS 3 EALAÍN CHLÚDAIGH COVER ART: AODÁN MONAGHAN 4 GLAS LE FÁS 5 Cruthaíonn Áras na bhFál an spreagadh do chomhrath. Mar gheall ar an spreagadh seo tá an gealltanas go n-athlonnófar postanna Faoin Leabhrán Seo About this booklet earnála poiblí sa Cheathrú Ghaeltachta. The Broadway Development creates a pulse for common prosperity. Tá an smaoineamh chun tosaigh go smior sa nádúr againn, ach Thinking ahead is very much part of our nature, but our With it comes the promise of the relocation of public sector jobs to the caithfidh obair s’againne díriú ar an chur i gcrích agus ar an chur i work must continue to be about implementation and Gaeltacht Quarter. bhfeidhm. Mar chaomhnóirí na Gaeilge agus an chultúir delivery. As custodians of the Irish Language and Ghaelaigh, caithfidh muid fosta bheith freagrach as na culture we must also account for the resources we use hacmhainní a úsáideann muid tríd an tairbhe do agus an tionchar by demonstrating clear community benefit and positive dhearfach shoiléir ar an phobal dá bharr a léiriú. Ach tá sin ina impact. But that is an equal challenge across chomhdhúshlán trasna an rialtais. Caithfidh an rialtais cruthú, Government. In allocating its resources it must agus é ag dáileadh acmhainní go bhfuil sé á dhéanamh le demonstrate equity in a manner that facilitates comhionannas a léiriú agus ar bhealach a ligeann do gach pobal achievement in all our communities. The Gaeltacht an chuid is fearr a bhaint amach ina áit féin. Is í triail litmis na Quarter is a litmus test of that commitment coimitminte seo ná an Cheathrú Ghaeltachta. -

Malachy Conway (National Trust)

COMMUNITY ARCHAEOLOGY IN NORTHERN IRELAND Community Archaeology in Northern Ireland Malachy Conway, Malachy Conway, TheArchaeological National Trust Conservation CBA Advisor Workshop, Leicester 12/09/09 A View of Belfast fromThe the National National Trust Trust, Northern property Ireland of Divis Re &g Thione Black Mountain Queen Anne House Dig, 2008 Castle Ward, Co. Down 1755 1813 The excavation was advertised as part of Archaeology Days in NI & through media and other publicity including production of fliers and banners and road signs. Resistivity Survey results showing house and other features Excavation aim to ’ground truth’ Prepared by Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork, QUB, 2007 the survey results through a series of test trenches, with support from NIEA, Built Heritage. Survey & Excavation 2008 Castle Ward, Co. Down All Photos by M. Conway (NT) Unless otherwise stated Excavation ran for 15 days (Wednesday-Sunday) in June 2008 and attracted 43 volunteers. The project was supported by NT archaeologist and 3 archaeologists from Centre for Archaeological Fieldwork (QUB), through funding by NIEA, Built Heritage. The volunteers were given on-site training in excavation and recording. Public access and tours were held throughout field work. The Downpatrick Branch of YAC was given a day on-site, where they excavated in separate trenches and were filmed and interview by local TV. Engagement & Research 2008 Public engagement Pointing the way to archaeology Castle Ward, Co. Down All Photos M. Conway (NT) Members of Downpatrick YAC on site YAC members setting up for TV interview! Engagement was one of the primary aims of this project, seeking to allow public to access and Take part in current archaeological fieldwork and research. -

Copy of Nipx List 16 Nov 07

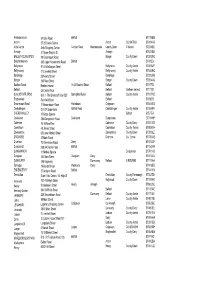

Andersonstown 57 Glen Road Belfast BT11 8BB Antrim 27-28 Castle Centre Antrim CO ANTRIM BT41 4AR Ards Centre Ards Shopping Centre Circular Road Newtownards County Down N Ireland BT23 4EU Armagh 31 Upper English St. Armagh BT61 7BA BALLEYHOLME SPSO 99 Groomsport Road Bangor County Down BT20 5NG Ballyhackamore 342 Upper Newtonards Road Belfast BT4 3EX Ballymena 51-63 Wellington Street Ballymena County Antrim BT43 6JP Ballymoney 11 Linenhall Street Ballymoney County Antrim BT53 6RQ Banbridge 26 Newry Street Banbridge BT32 3HB Bangor 143 Main Street Bangor County Down BT20 4AQ Bedford Street Bedford House 16-22 Bedford Street Belfast BT2 7FD Belfast 25 Castle Place Belfast Northern Ireland BT1 1BB BLACKSTAFF SPSO Unit 1- The Blackstaff Stop 520 Springfield Road Belfast County Antrim BT12 7AE Brackenvale Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 8EU Brownstown Road 11 Brownstown Road Portadown Craigavon BT62 4EB Carrickfergus CO-OP Superstore Belfast Road Carrickfergus County Antrim BT38 8PH CHERRYVALLEY 15 Kings Square Belfast BT5 7EA Coalisland 28A Dungannon Road Coalisland Dungannon BT71 4HP Coleraine 16-18 New Row Coleraine County Derry BT52 1RX Cookstown 49 James Street Cookstown County Tyrone BT80 8XH Downpatrick 65 Lower Market Street Downpatrick County Down BT30 6LZ DROMORE 37 Main Street Dromore Co. Tyrone BT78 3AE Drumhoe 73 Glenshane Raod Derry BT47 3SF Duncairn St 238-240 Antrim road Belfast BT15 2AR DUNGANNON 11 Market Square Dungannon BT70 1AB Dungiven 144 Main Street Dungiven Derry BT47 4LG DUNMURRY 148 Kingsway Dunmurray Belfast N IRELAND -

Appropriating Architecture: Violence, Surveillance and Anxiety in Belfast's Divis Flats Adam Page School of Hist

Title Page: Appropriating Architecture: Violence, Surveillance and Anxiety in Belfast’s Divis Flats Adam Page School of History and Heritage College of Arts University of Lincoln Brayford Pool Lincoln Lincolnshire LN6 7TSUK [email protected] 0044 (0)1522 835357 1 Biography: Page is a Lecturer in History at the University of Lincoln. He completed his PhD, which analyzed the transformation of cities into targets from interwar to Cold War, at the University of Sheffield in 2014. Before taking up the position at Lincoln, he was a fellow at the MECS Institute for Advanced Study, Leuphana Universität Lüneburg, He has published on air war and cities in Urban History and Contemporary European History. He is currently completing a book based on his PhD research, while developing a new project on disputed urban transformations in postwar UK cities. Abstract: In Belfast in the 1970s and 1980s, a modernist housing scheme became subject to multiple contested appropriations. Built between 1966 and 1972, the Divis Flats became a flashpoint in the violence of the Troubles, and a notorious space of danger, poverty, and decay. The structural and social failings of so many postwar system-built housing schemes were reiterated in Divis, as the rapid material decline of the complex echoed the descent into war in Belfast and Northern Ireland. Competing military and paramilitary strategies of violence refigured the topography of the flats, rendering the balcony walkways, narrow stairs, and lift shafts into an architecture of urban war. The residents viewed the complex as a concrete prison. They campaigned for the complete demolition of the flats, with protests which included attacking the architecture of the flats itself. -

Violence and the Sacred in Northern Ireland

VIOLENCE AND THE SACRED IN NORTHERN IRELAND Duncan Morrow University of Ulster at Jordanstown For 25 years Northern Ireland has been a society characterized not so much by violence as by an endemic fear of violence. At a purely statistical level the risk of death as a result of political violence in Belfast was always between three and ten times less than the risk of murder in major cities of the United States. Likewise, the risk of death as the result of traffic accidents in Northern Ireland has been, on average, twice as high as the risk of death by political killing (Belfast Telegraph, 23 January 1994). Nevertheless, the tidal flow of fear about political violence, sometimes higher and sometimes lower but always present, has been the consistent fundamental backdrop to public, and often private, life. This preeminence of fear is triggered by past and present circumstances and is projected onto the vision of the future. The experience that disorder is ever close at hand has resulted in an endemic insecurity which gives rise to the increasingly conscious desire for a new order, for scapegoats and for resolution. For a considerable period of time, Northern Ireland has actively sought and made scapegoats but such actions have been ineffective in bringing about the desired resolution to the crisis. They have led instead to a continuous mimetic crisis of both temporal and spatial dimensions. To have lived in Northern Ireland is to have lived in that unresolved crisis. Liberal democracy has provided the universal transcendence of Northern Ireland's political models. Northern Ireland is physically and spiritually close to the heartland of liberal democracy: it is geographically bound by Britain and Ireland, economically linked to Western Europe, and historically tied to emigration to the United States, Canada, and the South Pacific. -

Licensing Committee

LICENSING COMMITTEE Subject: Licences issued under Delegated Authority Date: 21st October, 2015 Reporting Officer: Trevor Martin, Head of Building Control, ext. 2450 Contact Officer: Stephen Hewitt, Building Control Manager, ext. 2435 Is this report restricted? Yes No X Is the decision eligible for Call-in? Yes No X 1.0 Purpose of Report/Summary of main Issues 1.1 Under the Scheme of Delegation the Director of Health and Environmental Services is responsible for exercising all powers in relation to the issue, but not refusal, of permits and licences, excluding provisions relating to the issue of entertainments licences where adverse representations have been made. For your information those applications dealt with under the Scheme are listed below. 2.0 Recommendation The Committee is requested to note the applications which have been issued under the Scheme of Delegation. 3.0 Main report 3.1 Key Issues Under the terms of the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) (Northern Ireland) Order 1985 the following Entertainment Licences were issued since your last meeting: Premises and Type of Hours licensed Applicant location application Accidental Theatre, 4th Floor, Wellington Buildings, 2-4 Wellington Mr Richard Grant Sun to Sat: 08.00 – 01.00 Street, Belfast, BT1 6HT. Lavery Premises and Type of Hours licensed Applicant Location application AM:PM, 38-44 Upper Sun: 12.30 – 00.00 Mr Eamon Arthur Street, Belfast, Renewal Mon to Sat: 11.30 – 01.00 McCusker BT1 4GH. Ardoyne Community Mr John Centre, 40 Herbert Street, Renewal Sun to Sat: 09.00 – 23.00 Flemming Belfast, BT14 7FE. Belfast Euro Christmas, Titanic Quarter, Mr Andrew Grant Sun to Sat: 11.30 – 23.00 Sydenham Road, Belfast, Simons BT3 9DT. -

The Irish Language in Education in Northern Ireland 2Nd Edition

Irish The Irish language in education in Northern Ireland 2nd edition This document was published by Mercator-Education with financial support from the Fryske Akademy and the European Commission (DG XXII: Education, Training and Youth) ISSN: 1570-1239 © Mercator-Education, 2004 The contents of this publication may be reproduced in print, except for commercial purposes, provided that the extract is proceeded by a complete reference to Mercator- Education: European network for regional or minority languages and education. Mercator-Education P.O. Box 54 8900 AB Ljouwert/Leeuwarden The Netherlands tel. +31- 58-2131414 fax: + 31 - 58-2131409 e-mail: [email protected] website://www.mercator-education.org This regional dossier was originally compiled by Aodán Mac Póilin from Ultach Trust/Iontaobhas Ultach and Mercator Education in 1997. It has been updated by Róise Ní Bhaoill from Ultach Trust/Iontaobhas Ultach in 2004. Very helpful comments have been supplied by Dr. Lelia Murtagh, Department of Psycholinguistics, Institúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann (ITE), Dublin. Unless stated otherwise the data reflect the situation in 2003. Acknowledgment: Mo bhuíochas do mo chomhghleacaithe in Iontaobhas ULTACH, do Liz Curtis, agus do Sheán Ó Coinn, Comhairle na Gaelscolaíochta as a dtacaíocht agus a gcuidiú agus mé i mbun na hoibre seo, agus don Roinn Oideachas agus an Roinn Fostaíochta agus Foghlama as an eolas a cuireadh ar fáil. Tsjerk Bottema has been responsible for the publication of the Mercator regional dossiers series from January 2004 onwards. Contents Foreword ..................................................1 1. Introduction .........................................2 2. Pre-school education .................................13 3. Primary education ...................................16 4. Secondary education .................................19 5. Further education ...................................22 6. -

Decisions Issued Between 9 August and 12 September 2016 No of Applications: 239

Decisions Issued Between 9 August and 12 September 2016 No of Applications: 239 Reference Number Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Decision Alterations to elevations of retail units 2, 3 and 4 involving recladding of front elevation using alucobond and render, glazed curtain walling Units 2 3 and 4 Connswater along west elevation, new entrance pod and Retail park 3 Connswater Link trolley park, loading bay, condenser units and LA04/2015/0161/F Lidl NI GmbH Belfast BT5 5DL relocation of fire escape doors. Permission Granted Proposed replacement main stand with seating for 1128. Basement parking with 2 upper levels, offices hospitality suites and proposed adjoining Cliftonville Football Club new replacement clubhouse and new vehicular Cliftonville Football Development Solitude Cliftonville Street access. Proposal also includes relocation of 1 LA04/2015/0163/F Centre c/o agent Belfast BT14 6L No. floodlighting column. Permission Granted Change of use of vacant / gap site to beer garden and terrace in association with adjacent North Down Leisure 3 Hill Street 151 Lisburn Road Belfast BT9 public house at No.149 Lisburn Road. Proposal LA04/2015/0344/F Belfast 5AJ includes balcony, canopy and dummy facade. Permission Granted Proposed 2 storey dwelling adjacent to existing LA04/2015/0363/F Mr R Marron 492 Donegall Road Belfast 2 storey dwelling Permission Refused John MCAllister 94 Gilnahirk 1 Hillsborough Drive Cregagh LA04/2015/0537/F Road Belfast BT5 7DJ Road Belfast BT6 Erection of a two storey dwelling Permission Granted Larkfield Builders Ltd 577-591 161 Glen Road Belfast BT11 LA04/2015/0597/F Falls Road Belfast BT11 9AB 8BN A single block (4 storey) of 11 apartments Permission Granted Reference Number Applicant Name & Address Location Proposal Decision Paul Molyneaux Sketirck Island 1-5 Gaffikin Street Belfast BT12 Residential development comprising 42 no.