Is a Fence the Best Defence? a Comparative Case-Study on the Influence of the Peace Lines on the Sense of Place and Identity of Residents in West-Belfast

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Halarose Borough Council

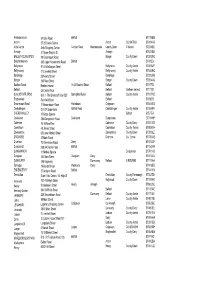

Electoral Office for Northern Ireland Election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly for the BELFAST NORTH Constituency NOTICE OF APPOINTMENT OF ELECTION AGENTS NOTICE IS HEREBY GIVEN that the following candidates have appointed or are deemed to have appointed the person named as election agent for the election of Members of the Northern Ireland Assembly on Thursday 5 May 2016. NAME AND ADDRESS OF NAME AND ADDRESS OF ADDRESS OF OFFICE TO WHICH CANDIDATE AGENT CLAIMS AND OTHER DOCUMENTS MAY BE SENT IF DIFFERENT FROM ADDRESS OF AGENT Ken Boyle Mr David Wynn Humphreys 56 Rathmore Drive, 5 Carnvue Park, Newtownabbey, Co Newtownabbey, Co Antrim, BT37 Antrim, BT36 6NQ 9BW Paula Jane Bradley Mr Nigel Dodds 39 Shore Road, Belfast, BT15 3PG (address in South Antrim 20 Castle Lodge, Banbridge, BT32 Constituency) 4RN Tom Burns Mr Thomas Carrick Burns 16B Station Road, Ballinderry 26 Cooldarragh Park, Belfast, BT14 Upper, Lisburn, BT28 2ET 6TG Lesley Carroll Mr Robert Foster (address in Belfast North 7 Dorchester Avenue, Glengormley, Constituency) Newtownabbey, BT36 5JL Geoff Dowey Mr Geoffrey Dowey (address in Belfast North 19a Carnmoney Road, Constituency) Newtownabbey, Co Antrim, BT36 6HL Fiona Ferguson Mr Matthew Collins 155 Northumberland Street, Mill House, (address in Belfast North 54 Ashton Park, Belfast, BT10 0JQ Office Unit 5, Belfast, BT13 2JF Constituency) Fra Hughes Mr Francis Wilfrid Hughes (address in Belfast North 19 Estoril Park, Belfast, BT14 7NG Constituency) William Humphrey Mr Nigel Dodds 39 Shore Road, Belfast, BT15 3PG -

Copy of Nipx List 16 Nov 07

Andersonstown 57 Glen Road Belfast BT11 8BB Antrim 27-28 Castle Centre Antrim CO ANTRIM BT41 4AR Ards Centre Ards Shopping Centre Circular Road Newtownards County Down N Ireland BT23 4EU Armagh 31 Upper English St. Armagh BT61 7BA BALLEYHOLME SPSO 99 Groomsport Road Bangor County Down BT20 5NG Ballyhackamore 342 Upper Newtonards Road Belfast BT4 3EX Ballymena 51-63 Wellington Street Ballymena County Antrim BT43 6JP Ballymoney 11 Linenhall Street Ballymoney County Antrim BT53 6RQ Banbridge 26 Newry Street Banbridge BT32 3HB Bangor 143 Main Street Bangor County Down BT20 4AQ Bedford Street Bedford House 16-22 Bedford Street Belfast BT2 7FD Belfast 25 Castle Place Belfast Northern Ireland BT1 1BB BLACKSTAFF SPSO Unit 1- The Blackstaff Stop 520 Springfield Road Belfast County Antrim BT12 7AE Brackenvale Saintfield Road Belfast BT8 8EU Brownstown Road 11 Brownstown Road Portadown Craigavon BT62 4EB Carrickfergus CO-OP Superstore Belfast Road Carrickfergus County Antrim BT38 8PH CHERRYVALLEY 15 Kings Square Belfast BT5 7EA Coalisland 28A Dungannon Road Coalisland Dungannon BT71 4HP Coleraine 16-18 New Row Coleraine County Derry BT52 1RX Cookstown 49 James Street Cookstown County Tyrone BT80 8XH Downpatrick 65 Lower Market Street Downpatrick County Down BT30 6LZ DROMORE 37 Main Street Dromore Co. Tyrone BT78 3AE Drumhoe 73 Glenshane Raod Derry BT47 3SF Duncairn St 238-240 Antrim road Belfast BT15 2AR DUNGANNON 11 Market Square Dungannon BT70 1AB Dungiven 144 Main Street Dungiven Derry BT47 4LG DUNMURRY 148 Kingsway Dunmurray Belfast N IRELAND -

Terrorism Knows No Borders

TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM TERRORISM KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS KNOWS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS NO BORDERS October 2019 his is a special initiative for SEFF to be associated with, it is one part of a three part overall Project which includes; the production of a Book and DVD Twhich captures the testimonies and experiences of well over 20 innocent victims and survivors of terrorism from across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland. The Project title; ‘Terrorism knows NO Borders’ aptly illustrates the broader point that we are seeking to make through our involvement in this work, namely that in the context of Northern Ireland terrorism and criminal violence was not curtailed to Northern Ireland alone but rather that individuals, families and communities experienced its’ impacts across the United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland and beyond these islands. This Memorial Quilt Project does not claim to represent the totality of lives lost across Great Britain and The Republic of Ireland but rather seeks to provide some understanding of the sacrifices paid by communities, families and individuals who have been victimised by ‘Republican’ or ‘Loyalist’ terrorism. SEFF’s ethos means that we are not purely concerned with victims/survivors who live within south Fermanagh or indeed the broader County. -

Walking the Street: No More Motorways for Belfast

Walking the Street: No more motorways for Belfast Martire, A. (2017). Walking the Street: No more motorways for Belfast. Spaces and Flows, 8(3), 35-61. https://doi.org/10.18848/2154-8676/CGP/v08i03/35-61 Published in: Spaces and Flows Document Version: Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Queen's University Belfast - Research Portal: Link to publication record in Queen's University Belfast Research Portal Publisher rights Copyright 2018 the authors. This is an open access article published under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/), which permits distribution and reproduction for non-commercial purposes, provided the author and source are cited. General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Queen's University Belfast Research Portal is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The Research Portal is Queen's institutional repository that provides access to Queen's research output. Every effort has been made to ensure that content in the Research Portal does not infringe any person's rights, or applicable UK laws. If you discover content in the Research Portal that you believe breaches copyright or violates any law, please contact [email protected]. Download date:27. Sep. 2021 VOLUME 8 ISSUE 3 Spaces and Flows: An International Journal of Urban and ExtraUrban -

For Sale/To Let

Instinctive Excellence in Property. For Sale/To Let Impressive Mixed Use Development Units ranging from 900sq ft to 3,300 sq ft 6 no. Shop Units Available Whitehall Square Sandy Row/Donegall Road Belfast BT12 5EU RETAIL/OFFICE For Sale/To Let Location The subject retail units are located on the busy Donegall Road, at the junction of Sandy Row. The units are located in Whitehall Square, which is a mixed use development consisting of apartments Retail/Office Premises and retail units. Whitehall Square Description Sandy Row/Donegall Road Belfast Ground floor retail units are completed to shell specification. They will be handed over to include electric roller shutters and polyester coated aluminium framed glazed shop front with main BT12 5EU services brought to a distribution point. Units are suitable for a variety of uses such as CTN, hairdressers, beauty salon or office space (subject to any necessary planning consent). RETAIL/OFFICE Accommodation Unit Sq Ft Sq M Price EPC—C53 Unit 1 1,329 124 £75,000 Unit 2 990 92 £60,000 Unit 3A 897 83 £55,000 Unit 3B 897 83 £55,000 Units 4 & 5 3,302 307 £185,000 Lease Terms Term: Negotiable CHRIS SWEENEY Repairs/Insurance: Full repairing and insuring basis. M: 07931 422 381 [email protected] Tenure Osborne King We assume that the property is held in Freehold or Long Leasehold, subject to a The Metro Building nominal ground rent. 6-9 Donegall Square South Belfast, BT1 5JA T: 028 9027 0000 VAT E: [email protected] All prices, rentals and outgoings are quoted exclusive of, but may be liable to VAT. -

Development Brief For

284-296 SHANKILL ROAD, BELFAST DEVELOPMENT BRIEF The Department for Social Development invites proposals for the development of 284-296 Shankill Road, Belfast. September 2015 CONTENTS 1 Introduction and Strategic Context 2 The Site 3 Vision Statement 4 Design Brief 5 Conditions of Development and Disposal of Site 6 Submission of Proposals 7 Selection of a Developer 8 Urban Development Grant 9 Disclaimer 10 Further Queries Appendix A 1. INTRODUCTION AND STRATEGIC CONTEXT 1.1 The Department for Social Development (the Department) invites proposals for the development of 284-296 Shankill Road, Belfast. Proposals should be submitted by not later than 12 noon on 10th December 2015. 1.2 The overall objective of the competition is to promote sustainable urban regeneration by selecting a high quality development proposal that also meets the Department’s regeneration objectives for the local area. In seeking to work in partnership with the private sector, the Department recognizes the contribution that this sector can make to urban regeneration in terms of innovative, high quality design, professional expertise and financing. 1.3 The Department plays the lead role in promoting and co-ordinating the implementation of urban regeneration programmes and schemes in towns and city centres throughout Northern Ireland. Belfast Regeneration Directorate carries out this role in areas of Belfast outside the City Centre. 1.4 The Department’s statutory regeneration authority derives from: . The Planning (NI) Order 1991 which provides the legislative basis for comprehensive development schemes, land acquisition and disposal of land, and the extinguishment of public rights of way; and, . The Social Need (NI) Order 1986 which provides the statutory basis for granting financial assistance to projects in areas of special social need and undertaking environmental improvement schemes. -

Northern Irish Society in the Wake of Brexit

Northern Irish Society in the Wake of Brexit By Agnès Maillot Since the 2016 referendum, Brexit has dominated the political conversation in Northern Ireland, launching a debate on the Irish reunification and exacerbating communitarian tensions within Northern Irish society. What are the social and economic roots of these conflicts, and what is at stake for Northern Ireland’s future? “No Irish sea border”, “EU out of Ulster”, “NI Protocol makes GFA null and void”. These are some of the graffiti that have appeared on the walls of some Northern Irish communities in recent weeks. They all express Loyalist1 frustration, and sometimes anger, towards the terms of the Withdrawal Agreement reached in 2019 between the UK and the EU, which includes a specific section on Northern Ireland.2 While the message behind these phrases might seem cryptic to the outsider, it is a language that most of the Irish, and more specifically Northern Irish, can speak fluently. For the last four years, Brexit has regularly been making the news headlines and has dominated political conversations. More importantly, it has introduced a new dimension in the way in which the future of the UK province is discussed, prompting a debate on the reunification of the island and exacerbating a crisis within Unionism. Brexit has destabilised the Unionist community, whose sense of identity had already been tested over the last twenty years by the Peace process, by the 1 In Northern Ireland, the two main political families are Unionism (those bent on maintaining the Union with the2 The UK) withdrawal and Nationalis agreementm, wh wasich reached strives into Octoberachieve 2019a United and subsequentlyIreland. -

Belfast on the Move: Transport Masterplan for Belfast City Centre

Belfast on the Move: Transport Masterplan for Belfast City Centre The South Belfast Partnership Board are supportive of the overall aims of the proposed Masterplan, particularly the need to improve the ease and safety for pedestrians and cyclists accessing and moving around the city centre, improving public transport services, reducing the impact of traffic and maximizing opportunities to create a high quality public realm within the city centre. We are committed to supporting the key principles within the Belfast Metropolitan Transport Plan 2015, which we believe are adequately embedded within the draft Masterplan. Within this context, we would like to take this opportunity to make a number of comments in relation to both the Sustainable Transport Enabling Measures and the longer-term proposals for delivering a high quality transport system for the City Centre. Sustainable Transport Enabling Measures We understand that the Sustainable Transport Enabling Measures are part of a longer terms strategy to improve the pedestrian environment and public transport services within the City Centre. However, whilst we would welcome most of the changes proposed, which we believe will help to improve cycling and walking and the reliability of bus services, we would wish to raise concerns regarding the proposed traffic management to the west side of the City Centre. Firstly, it is unclear from the proposals whether the lower section of Sandy Row, from Hope Street to Grosvenor Road, will remain two-way or be converted to a one- way street. Assuming that it remains as it currently is, we would have concerns that the existing road lacks the capacity to carry the increased traffic flow that is likely to result from the proposals. -

The Agreed Truth & the Real Truth

14 | VARIANT 29 | SUMMER 2007 The Agreed Truth & The Real Truth: The New Northern Ireland Liam O’Ruairc The ‘historic’ restoration of devolution in Northern UK national average of 100.8 The province is on Notes Ireland, on 8 May 2007, has been hailed by the life support from the British government: in a 1 Gerry Moriarty and Deaglán de media as marking the symbolic end of the conflict recent editorial, The Economist characterised the Bréadún, ‘Stormont ceremony there.1 Like most aspects of the peace process, North as a “subsidy junkie” that receives every marks end of Northern conflict’, Irish Times, 8 May 2007 the opening of the Assembly was “carefully stage year from Westminster £5bn more than is raised managed to present a positive and progressive locally in taxation.9 Compared to the 720,000 at 2 Colm Heatley, ‘United Fronts as parties vie for success’, Sunday 2 image.” This is in line with news reports about work, there are 530,000 ‘economically inactive’ in Business Post, 6 May 2007 the North being dominated by the ‘success the workforce (the term ‘economically inactive’ 3 Editorial, ‘Ulster moves forward’, story’ of the ‘New Northern Ireland’. “There is covers anyone neither employed nor receiving The Times, 5 October 2006. See an optimism and realism in Northern Ireland unemployment-related benefits, including the also Editorial, ‘A sign of rising today that is dissolving ancient prejudices and long-term sick and disabled, students, carers confidence’, The Independent, 3 boosting business confidence, the essential and the retired. In Northern Ireland, only 8% of February 2007 underpinning for growth and prosperity. -

“Methinks I See Grim Slavery's Gorgon Form”: Abolitionism in Belfast, 1775

“Methinks I see grim Slavery’s Gorgon form”: Abolitionism in Belfast, 1775-1865 By Krysta Beggs-McCormick (BA Hons, MRes) Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences of Ulster University A Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) October 2018 I confirm that the word count of this thesis is less than 100,000 words. Contents Acknowledgements ………………………………………………………………………… I Illustration I …………………………………………………………………………...…… II Abstract ……………………………………………………………………………………. III Introduction ………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Chapter One – “That horrible degradation of human nature”: Abolitionism in late eighteenth-century Belfast ……………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 22 Chapter Two – “Go ruthless Avarice”: Abolitionism in nineteenth century Georgian Belfast ………………………………………………………………………................................... 54 Chapter Three – “The atrocious system should come to an end”: Abolitionism in Early Victorian Belfast, 1837-1857 ……………………………………………………………... 99 Chapter Four - “Whether freedom or slavery should be the grand characteristic of the United States”: Belfast Abolitionism and the American Civil War……………………..………. 175 Conclusion ……………………………………………………………………………….. 206 Bibliography ……………………………………………………………………………... 214 Appendix 1: Table ……………………………………………………………………….. 257 Appendix 2: Belfast Newspapers .…………….…………………………………………. 258 I Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been possible without the help and guidance of many people to whom I am greatly indebted. I owe my greatest thanks to my supervisory team: Professor -

Legacies of the Troubles and the Holy Cross Girls Primary School Dispute

Glencree Journal 2021 “IS IT ALWAYS GOING BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Eimear Rosato 198 Glencree Journal 2021 Legacy of the Troubles and the Holy Cross School dispute “IS IT ALWAYS GOING TO BE THIS WAY?”: LEGACIES OF THE TROUBLES AND THE HOLY CROSS GIRLS PRIMARY SCHOOL DISPUTE Abstract This article examines the embedded nature of memory and identity within place through a case study of the Holy Cross Girls Primary School ‘incident’ in North Belfast. In 2001, whilst walking to and from school, the pupils of this primary school aged between 4-11 years old, faced daily hostile mobs of unionist/loyalists protesters. These protesters threw stones, bottles, balloons filled with urine, fireworks and other projectiles including a blast bomb (Chris Gilligan 2009, 32). The ‘incident’ derived from a culmination of long- term sectarian tensions across the interface between nationalist/republican Ardoyne and unionist/loyalist Glenbryn. Utilising oral history interviews conducted in 2016–2017 with twelve young people from the Ardoyne community, it will explore their personal experiences and how this event has shaped their identities, memory, understanding of the conflict and approaches to reconciliation. KEY WORDS: Oral history, Northern Ireland, intergenerational memory, reconciliation Introduction Legacies and memories of the past are engrained within territorial boundaries, sites of memory and cultural artefacts. Maurice Halbwachs (1992), the founding father of memory studies, believed that individuals as a group remember, collectively or socially, with the past being understood through ritualism and symbols. Pierre Nora’s (1989) research builds and expands on Halbwachs, arguing that memory ‘crystallises’ itself in certain sites where a sense of historical continuity persists. -

Travelling with Translink

Belfast Bus Map - Metro Services Showing High Frequency Corridors within the Metro Network Monkstown Main Corridors within Metro Network 1E Roughfort Milewater 1D Mossley Monkstown (Devenish Drive) Road From every From every Drive 5-10 mins 15-30 mins Carnmoney / Fairview Ballyhenry 2C/D/E 2C/D/E/G Jordanstown 1 Antrim Road Ballyearl Road 1A/C Road 2 Shore Road Drive 1B 14/A/B/C 13/A/B/C 3 Holywood Road Travelling with 13C, 14C 1A/C 2G New Manse 2A/B 1A/C Monkstown Forthill 13/A/B Avenue 4 Upper Newtownards Rd Mossley Way Drive 13B Circular Road 5 Castlereagh Road 2C/D/E 14B 1B/C/D/G Manse 2B Carnmoney Ballyduff 6 Cregagh Road Road Road Station Hydepark Doagh Ormeau Road Road Road 7 14/A/B/C 2H 8 Malone Road 13/A/B/C Cloughfern 2A Rathfern 9 Lisburn Road Translink 13C, 14C 1G 14A Ballyhenry 10 Falls Road Road 1B/C/D Derrycoole East 2D/E/H 14/C Antrim 11 Shankill Road 13/A/B/C Northcott Institute Rathmore 12 Oldpark Road Shopping 2B Carnmoney Drive 13/C 13A 14/A/B/C Centre Road A guide to using passenger transport in Northern Ireland 1B/C Doagh Sandyknowes 1A 16 Other Routes 1D Road 2C Antrim Terminus P Park & Ride 13 City Express 1E Road Glengormley 2E/H 1F 1B/C/F/G 13/A/B y Single direction routes indicated by arrows 13C, 14C M2 Motorway 1E/J 2A/B a w Church Braden r Inbound Outbound Circular Route o Road Park t o Mallusk Bellevue 2D M 1J 14/A/B Industrial M2 Estate Royal Abbey- M5 Mo 1F Mail 1E/J torwcentre 64 Belfast Zoo 2A/B 2B 14/A/C Blackrock Hightown a 2B/D Square y 64 Arthur 13C Belfast Castle Road 12C Whitewell 13/A/B 2B/C/D/E/G/H