Arxiv:1907.02434V1 [Cs.CY] 4 Jul 2019 1 Introduction

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

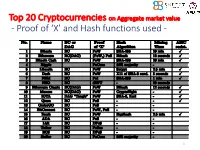

Proof of 'X' and Hash Functions Used

Top 20 Cryptocurrencies on Aggregate market value - Proof of ‘X’ and Hash functions used - 1 ISI Kolkata BlockChain Workshop, Nov 30th, 2017 CRYPTOGRAPHY with BlockChain - Hash Functions, Signatures and Anonymization - Hiroaki ANADA*1, Kouichi SAKURAI*2 *1: University of Nagasaki, *2: Kyushu University Acknowledgements: This work is supported by: Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research of Japan Society for the Promotion of Science; Research Project Number: JP15H02711 Top 20 Cryptocurrencies on Aggregate market value - Proof of ‘X’ and Hash functions used - 3 Table of Contents 1. Cryptographic Primitives in Blockchains 2. Hash Functions a. Roles b. Various Hash functions used for Proof of ‘X’ 3. Signatures a. Standard Signatures (ECDSA) b. Ring Signatures c. One-Time Signatures (Winternitz) 4. Anonymization Techniques a. Mixing (CoinJoin) b. Zero-Knowledge proofs (zk-SNARK) 5. Conclusion 4 Brief History of Proof of ‘X’ 1992: “Pricing via Processing or Combatting Junk Mail” Dwork, C. and Naor, M., CRYPTO ’92 Pricing Functions 2003: “Moderately Hard Functions: From Complexity to Spam Fighting” Naor, M., Foundations of Soft. Tech. and Theoretical Comp. Sci. 2008: “Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system” Nakamoto, S. Proof of Work 5 Brief History of Proof of ‘X’ 2008: “Bitcoin: A peer-to-peer electronic cash system” Nakamoto, S. Proof of Work 2012: “Peercoin” Proof of Stake (& Proof of Work) ~ : Delegated Proof of Stake, Proof of Storage, Proof of Importance, Proof of Reserves, Proof of Consensus, ... 6 Proofs of ‘X’ 1. Proof of Work 2. Proof of Stake Hash-based Proof of ‘X’ 3. Delegated Proof of Stake 4. Proof of Importance 5. -

A Regulatory System for Optimal Legal Transaction Throughput in Cryptocurrency Blockchains

A Regulatory System for Optimal Legal Transaction Throughput in Cryptocurrency Blockchains Aditya Ahuja Vinay J. Ribeiro Ranjan Pal Indian Institute of Technology Indian Institute of Technology University of Michigan Delhi Bombay Ann Arbor, USA New Delhi, India Mumbai, India [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT correctness of the underlying computational principles, which are a Permissionless blockchain consensus protocols have been designed basis of the efficacy of these economies. More specifically, in order primarily for defining decentralized economies for the commercial to sustain these cryptocurrency based decentralized economies, trade of assets, both virtual and physical, using cryptocurrencies. blockchain consensus protocols serve as a technical foundation. In most instances, the assets being traded are regulated, which man- Existing blockchain protocols for cryptocurrencies address one dates that the legal right to their trade and their trade value are of (or any combination of) the following system goals: speed, se- determined by the governmental regulator of the jurisdiction in curity and decentralization. Unfortunately, these system goals are which the trade occurs. Unfortunately, existing blockchains do not necessary but insufficient. Illegal activities propelled through the formally recognise proposal of legal cryptocurrency transactions, as strategic use of blockchain based cryptocurrencies, is a serious part of the execution of their respective consensus protocols, result- problem staring at the face of many world governments today ing in rampant illegal activities in the associated crypto-economies. [47]. These illegal activities exploit the permissionless nature of In this contribution, we motivate the need for regulated blockchain the blockchain networks for illegal trade, to strategically defeat consensus protocols with a case study of the illegal, cryptocurrency regulation by obfuscating the jurisdictions of the blockchain users based, Silk Road darknet market. -

Incentives in Ethereum's Hybrid Casper Protocol

Incentives in Ethereum’s Hybrid Casper Protocol Vitalik Buterin∗, Daniel¨ Reijsbergeny, Stefanos Leonardosy, Georgios Piliourasy ∗Ethereum Foundation ySingapore University of Technology and Design Abstract We present an overview of hybrid Casper the Friendly Finality Gadget (FFG): a Proof-of-Stake checkpointing protocol overlaid onto Ethereum’s Proof-of-Work blockchain. We describe its core functionalities and reward scheme, and explore its properties. Our findings indicate that Casper’s implemented incentives mechanism ensures liveness, while providing safety guarantees that improve over standard Proof-of-Work protocols. Based on a minimal-impact implementation of the protocol as a smart contract on the blockchain, we discuss additional issues related to parametrisation, funding, throughput and network overhead and detect potential limitations. Index Terms Proof of Stake, Ethereum, Consensus I. INTRODUCTION In 2008, the seminal Bitcoin paper by Satoshi Nakamoto [50] introduced the blockchain as a means for an open network to extend and reach consensus about a distributed ledger of digital token transfers. The main innovation of Ethereum [16] was to use the blockchain to maintain a history of code creation and execution. As such, Ethereum functions as a global computer that executes code uploaded by users in the form of smart contracts. Like Bitcoin [31], [32], Ethereum’s block proposal mechanism is based on the concept of Proof-of-Work (PoW). In PoW, network participants utilise computational power to win the right to add blocks to the blockchain. However, the alarming global energy consumption of PoW-based blockchains has made the concept increasingly controversial [22], [45], [65]. One of the main alternatives to PoW is virtual mining or Proof-of-Stake (PoS) [1], [5], [46], [55]. -

Building Applications on the Ethereum Blockchain

Building Applications on the Ethereum Blockchain Eoin Woods Endava @eoinwoodz licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License 1 Agenda • Blockchain Recap • Ethereum • Application Design • Development • (Solidity – Ethereum’s Language) • Summary 3 Blockchain Recap 4 What is Blockchain? • Enabling technology of Bitcoin, Ethereum, … • Distributed database without a controlling authority • Auditable database with provable lineage • A way to collaborate with parties without direct trust • Architectural component for highly distributed Internet-scale systems 5 Architectural Characteristics of a Blockchain • P2P distributed • (Very) eventual consistency • Append only “ledger” • Computationally expensive • Cryptographic security • Limited query model (key only) (integrity & non-repudiation) • Lack of privacy (often) • Eventual consistency • low throughput scalability • Smart contracts (generally – 10s txn/sec) • Fault tolerant reliability 6 What Makes a Good Blockchain Application? • Multi-organisational • No complex query requirement • No trusted intermediary • Multiple untrusted writers • Need shared source of state • Latency insensitive (e.g. transactions, identity) • Relatively low throughput • Need for immutability (e.g. proof • Need for resiliency of existence) • Transaction interactions • Fairly small data size “If your requirements are fulfilled by today’s relational databases, you’d be insane to use a blockchain” – Gideon Greenspan 7 What is Blockchain being Used For? digital ledger that tracks and derivatives post- verifiable supply chains supply chain efficiency protects valuable assets trade processing Keybase Georgia government Identity management verified data post-trade processing records 8 Public and Permissioned Blockchains Public Permissioned Throughput Low Medium Latency High Medium # Readers High High # Writers High Low Centrally Managed No Yes Transaction Cost High “Free” Based on: Do you need a Blockchain? Karl Wüst, Arthur Gervaisy IACR Cryptology ePrint Archive, 2017, p.375. -

Algorand: Scaling Byzantine Agreements for Cryptocurrencies Yossi Gilad, Rotem Hemo, Silvio Micali, Georgios Vlachos, Nickolai Zeldovich MIT CSAIL

Algorand: Scaling Byzantine Agreements for Cryptocurrencies Yossi Gilad, Rotem Hemo, Silvio Micali, Georgios Vlachos, Nickolai Zeldovich MIT CSAIL ABSTRACT open setting: since anyone can participate, an adversary can create an arbitrary number of pseudonyms (“Sybils”) [21], Algorand is a new cryptocurrency that confirms transactions making it infeasible to rely on traditional consensus proto- with latency on the order of a minute while scaling to many cols [15] that require a fraction of honest users. users. Algorand ensures that users never have divergent views of confirmed transactions, even if some of the users Bitcoin [41] and other cryptocurrencies [23, 53] address are malicious and the network is temporarily partitioned. this problem using proof-of-work (PoW), where users must In contrast, existing cryptocurrencies allow for temporary repeatedly compute hashes to grow the blockchain, and forks and therefore require a long time, on the order of an the longest chain is considered authoritative. PoW ensures hour, to confirm transactions with high confidence. that an adversary does not gain any advantage by creating Algorand uses a new Byzantine Agreement (BA) protocol pseudonyms. However, PoW allows the possibility of forks, to reach consensus among users on the next set of trans- where two different blockchains have the same length, and actions. To scale the consensus to many users, Algorand neither one supersedes the other. Mitigating forks requires uses a novel mechanism based on Verifiable Random Func- two unfortunate sacrifices: the time to grow the chain byone tions that allows users to privately check whether they are block must be reasonably high (e.g., 10 minutes in Bitcoin), selected to participate in the BA to agree on the next set and applications must wait for several blocks in order to of transactions, and to include a proof of their selection in ensure their transaction remains on the authoritative chain their network messages. -

Blockchain Consensus: an Analysis of Proof-Of-Work and Its Applications. Amitai Porat1, Avneesh Pratap2, Parth Shah3, and Vinit Adkar4

Blockchain Consensus: An analysis of Proof-of-Work and its applications. Amitai Porat1, Avneesh Pratap2, Parth Shah3, and Vinit Adkar4 [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT Blockchain Technology, having been around since 2008, has recently taken the world by storm. Industries are beginning to implement blockchain solutions for real world services. In our project, we build a Proof of Work based Blockchain consensus protocol and evauluate how major applications can run on the underlying platform. We also explore how varying network conditions vary the outcome of consensus among nodes. Furthermore, to demonstrate some of its capabilities we created our own application built on the Ethereum blockchain platform. While Bitcoin is by and far the first major cryptocurrency, it is limited in the capabilities of its blockchain as a peer-to-peer currency exchange. Therefore, Ethereum blockchain was the right choice for application development since it caters itself specifically to building decentralized applications that seek rapid deployment and security. 1 Introduction Blockchain technology challenges traditional shared architectures which require forms of centralized governance to assure the integrity of internet applications. It is the first truly democratized, universally accessible, shared and secure asset control architecture. The first blockchain technology was founded shortly after the US financial collapse in 2008, the idea was a decentralized peer-to-peer currency transfer network that people can rely on when the traditional financial system fails. As a result, blockchain largely took off and made its way into large public interest. We chose to investigate the power of blockchain consensus algorithms, primarily Proof of Work. -

Survey on Surging Technology: Cryptocurrency

International Journal of Engineering &Technology, 7 (3.12) (2018) 296-299 International Journal of Engineering & Technology Website: www.sciencepubco.com/index.php/IJET Research paper Survey on Surging Technology: Cryptocurrency Swathi Singh1, Suguna R2, Divya Satish3, Ranjith Kumar MV4 1Research Scholar, 2, 3Professor, 4Assistant Professor 1,2,3,4Department of Computer Science and Engineering, 1,3SKR Engineering College, Chennai, India, 2Vel Tech Rangarajan Dr.Sagunthala Institute of Science and Technology, Chennai, India 4SRM Institute of Science and Technology, Kattankulathur, Chennai. *Corresponding Author Email: [email protected] Abstract The paper gives an insight on cryptography within digital money used in electronic commerce. The combination of digital currencies with cryptography is named as cryptocurrencies or cryptocoins. Though this technique came into existence years ago, it is bound to have a great future due to its flexibility and very less or nil transaction costs. The concept of cryptocurrency is not new in digital world and is already gaining subtle importance in electronic commerce market. This technology can bring down various risks that may have occurred in usage of physical currencies. The transaction of cryptocurrencies are protected with strong cryptographic hash functions that ensure the safe sending and receiving of assets within the transaction chain or blockchain in a Peer-to-Peer network. The paper discusses the merits and demerits of this technology with a wide range of applications that use cryptocurrency. Index Terms: Blockchain, Cryptocurrency. However, the first implementation of Bitcoin protocol routed 1. Introduction many other cryptocurrencies to exist. Bitcoin is a self-regulatory system that is not supported by government or any organization. -

Robust Proof of Stake: a New Consensus Protocol for Sustainable Blockchain Systems

sustainability Article Robust Proof of Stake: A New Consensus Protocol for Sustainable Blockchain Systems Aiya Li 1, Xianhua Wei 1 and Zhou He 1,2,* 1 School of Economics and Management, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China; [email protected] (A.L.); [email protected] (X.W.) 2 Key Laboratory of Big Data Mining and Knowledge Management, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing 100190, China * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 1 March 2020; Accepted: 31 March 2020; Published: 2 April 2020 Abstract: In the digital economy era, the development of a distributed robust economy system has become increasingly important. The blockchain technology can be used to build such a system, but current mainstream consensus protocols are vulnerable to attack, making blockchain systems unsustainable. In this paper, we propose a new Robust Proof of Stake (RPoS) consensus protocol, which uses the amount of coins to select miners and limits the maximum value of the coin age to effectively avoid coin age accumulation attack and Nothing-at-Stake (N@S) attack. Under a comparison framework, we show that the RPoS equals or outperforms Proof of Work (PoW) protocol and Proof of Stake (PoS) protocol in three dimensions: energy consumption, robustness, and transaction processing speed. To compare the three consensus protocols in terms of trade efficiency, we built an agent-based model and find that RPoS protocol has greater or similar trade request-satisfied ratio than PoW and PoS. Hence, we suggest that RPoS is very suitable for building a robust digital economy distributed system. Keywords: distributed digital economy system; blockchain; robust; consensus protocol; agent-based model 1. -

Research and Applied Perspective to Blockchain Technology: a Comprehensive Survey

applied sciences Review Research and Applied Perspective to Blockchain Technology: A Comprehensive Survey Sumaira Johar 1,* , Naveed Ahmad 1, Warda Asher 1, Haitham Cruickshank 2 and Amad Durrani 1 1 Department of Computer Science, University of Peshawar, Peshawar 25000, Pakistan; [email protected] (N.A.); [email protected] (W.A.); [email protected] (A.D.) 2 Institute of Communication Systems, University of Surrey, Guildford GU2 7JP, UK; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Blockchain being a leading technology in the 21st century is revolutionizing each sector of life. Services are being provided and upgraded using its salient features and fruitful characteristics. Businesses are being enhanced by using this technology. Countries are shifting towards digital cur- rencies i.e., an initial application of blockchain application. It omits the need of central authority by its distributed ledger functionality. This distributed ledger is achieved by using a consensus mechanism in blockchain. A consensus algorithm plays a core role in the implementation of blockchain. Any application implementing blockchain uses consensus algorithms to achieve its desired task. In this paper, we focus on provisioning of a comparative analysis of blockchain’s consensus algorithms with respect to the type of application. Furthermore, we discuss the development platforms as well as technologies of blockchain. The aim of the paper is to provide knowledge from basic to extensive from blockchain architecture to consensus methods, from applications to development platform, from challenges and issues to blockchain research gaps in various areas. Citation: Johar, S.; Ahmad, N.; Keywords: blockchain; applications; consensus mechanisms Asher, W.; Cruickshank, H.; Durrani, A. -

A Survey on Consensus Mechanisms and Mining Strategy Management

1 A Survey on Consensus Mechanisms and Mining Strategy Management in Blockchain Networks Wenbo Wang, Member, IEEE, Dinh Thai Hoang, Member, IEEE, Peizhao Hu, Member, IEEE, Zehui Xiong, Student Member, IEEE, Dusit Niyato, Fellow, IEEE, Ping Wang, Senior Member, IEEE Yonggang Wen, Senior Member, IEEE and Dong In Kim, Fellow, IEEE Abstract—The past decade has witnessed the rapid evolution digital tokens between Peer-to-Peer (P2P) users. Blockchain in blockchain technologies, which has attracted tremendous networks, especially those adopting open-access policies, are interests from both the research communities and industries. The distinguished by their inherent characteristics of disinterme- blockchain network was originated from the Internet financial sector as a decentralized, immutable ledger system for transac- diation, public accessibility of network functionalities (e.g., tional data ordering. Nowadays, it is envisioned as a powerful data transparency) and tamper-resilience [2]. Therefore, they backbone/framework for decentralized data processing and data- have been hailed as the foundation of various spotlight Fin- driven self-organization in flat, open-access networks. In partic- Tech applications that impose critical requirement on data ular, the plausible characteristics of decentralization, immutabil- security and integrity (e.g., cryptocurrencies [3], [4]). Further- ity and self-organization are primarily owing to the unique decentralized consensus mechanisms introduced by blockchain more, with the distributed consensus provided by blockchain networks. This survey is motivated by the lack of a comprehensive networks, blockchains are fundamental to orchestrating the literature review on the development of decentralized consensus global state machine1 for general-purpose bytecode execution. mechanisms in blockchain networks. In this survey, we provide a Therefore, blockchains are also envisaged as the backbone systematic vision of the organization of blockchain networks. -

Paycrypto: Proof-Of-Stake Vs Proof-Of-Work

Turkish Journal of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation; 32(3) ISSN 2651-4451 | e-ISSN 2651-446X PAYCRYPTO: PROOF-OF-STAKE VS PROOF-OF-WORK Ms. S Durga Devi1, Mrs. G K Sandhia2 1SRM Institute of Science and Technology, [email protected] 2SRM Institute of Science and Technology, [email protected] ABSTRACT Proof-of-work has been the mechanism used to validate transactions on a blockchain for a long period of time. The security of the chain however lies on the computational complexity of the puzzle and thus the energy consumption to solve the problem. Proof-of-stake is an alternate mechanism that could reward participants to deposit their coins. This stake is used as a factor to validate transactions thus finding a energy viable way to approve transactions without compromising security levels of the chain I. INTRODUCTION Since the conception of cryptocurrencies(Bitcoin 2008), proof-of-work has been the primary mechanism used to achieve consensus on blockchain networks. The idea of proof-of-work has been the key factor in deciding the security and minting model of Bitcoin. In recent times, due to the inception of an idea called coinage, a different mechanism called proof-of-stake has been proposed. Proof-of-stake since then, has been formalized to build a secure model of peer-to-peer cryptocurrency and minting process. The proof-of-stake concept tries to find a viable mechanism for the future of cryptocurrencies where security of a chain does not depend upon on energy consumption II. BACKGROUND Exchange of money on the internet relies entirely around financial institutions acting as trusted third parties to facilitate transactions. -

Design and Implementation of a Proof-Of-Stake Consensus Algorithm for Blockchain

Design and Implementation of a Proof-of-Stake Consensus Algorithm for Blockchain Final degree thesis By Eric Garcia Ribera January 2018 Director: Albert Cabellos Co-Director: Jordi Paillissé Specialization: Information Technologies 2 Abstract There is a great deal of talk about Bitcoin[1] and the blockchain among a lot of sectors in the security community as the system works without a central repository or a single administrator and without the use of digital certificates. Blockchain technology is said to be a new solution to a well-know problem in fault-tolerant distributed systems, the Byzantine Generals problem. This document analyzes and describes a consensus algorithm implementation that will be a core part of a blockchain prototype whose main purpose is to allocate, delegate and bind IP addresses in a decentralized and secure way. The objective of the algorithm is to allow the prototype determine which par- ticipants are able to add new blocks on the blockchain in a totally random and unpredictable manner. 1 Resumen Últimamente se esta hablando mucho de Bitcoin[1] y la tecnología que utiliza, llamada blockchain o cadena de bloques, en distintos sectores relacionados con la seguridad de la red, ya que dicha tecnología proporciona una descentralización total de los sistemas y además, ofrece un funcionamiento seguro sin la necesi- dad de usar certificados digitales. De echo, se cree que la tecnología blockchain proporciona soluciones al problema de los generales bizantinos en sistemas dis- tribuidos. Este documento analiza y describe la implementación de un algoritmo de con- senso que será una parte fundamental en un prototipo de blockchain cuyo prin- cipal objetivo es el de asignar, delegar y vincular direcciones IP de un modo descentralizado y seguro.