A Linguistic Study of the French Press's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sénat Proposition De Résolution

N° 428 SÉNAT SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 2008-2009 Annexe au procès-verbal de la séance du 20 mai 2009 PROPOSITION DE RÉSOLUTION tendant à modifier le Règlement du Sénat pour mettre en œuvre la révision constitutionnelle, conforter le pluralisme sénatorial et rénover les méthodes de travail du Sénat, TEXTE DE LA COMMISSION DES LOIS CONSTITUTIONNELLES, DE LÉGISLATION, DU SUFFRAGE UNIVERSEL, DU RÈGLEMENT ET D’ADMINISTRATION GÉNÉRALE (1), (1) Cette commission est composée de : M. Jean-Jacques Hyest, président ; M. Nicolas Alfonsi, Mme Nicole Borvo Cohen-Seat, MM. Patrice Gélard, Jean-René Lecerf, Jean-Claude Peyronnet, Jean-Pierre Sueur, Mme Catherine Troendle, M. François Zocchetto, vice-présidents ; MM. Laurent Béteille, Christian Cointat, Charles Gautier, Jacques Mahéas, secrétaires ; M. Alain Anziani, Mmes Éliane Assassi, Nicole Bonnefoy, Alima Boumediene-Thiery, MM. Elie Brun, François-Noël Buffet, Pierre-Yves Collombat, Jean-Patrick Courtois, Mme Marie-Hélène Des Esgaulx, M. Yves Détraigne, Mme Anne-Marie Escoffier, MM. Pierre Fauchon, Louis-Constant Fleming, Gaston Flosse, Christophe-André Frassa, Bernard Frimat, René Garrec, Jean-Claude Gaudin, Mmes Jacqueline Gourault, Virginie Klès, MM. Antoine Lefèvre, Dominique de Legge, Mme Josiane Mathon-Poinat, MM. Jacques Mézard, Jean-Pierre Michel, François Pillet, Hugues Portelli, Roland Povinelli, Bernard Saugey, Simon Sutour, Richard Tuheiava, Alex Türk, Jean-Pierre Vial, Jean-Paul Virapoullé, Richard Yung. Voir le(s) numéro(s) : Sénat : 377 et 427 (2008-2009) - 3 - PROPOSITION DE RÉSOLUTION TENDANT À MODIFIER LE RÈGLEMENT DU SÉNAT POUR METTRE EN ŒUVRE LA RÉVISION CONSTITUTIONNELLE, CONFORTER LE PLURALISME SÉNATORIAL ET RÉNOVER LES MÉTHODES DE TRAVAIL DU SÉNAT Article 1er Composition du Bureau du Sénat I. -

Du Premier Au Second Gouvernement Temaru: Une Annee De Crise Politique Et Institutionnelle

1 DU PREMIER AU SECOND GOUVERNEMENT TEMARU: UNE ANNEE DE CRISE POLITIQUE ET INSTITUTIONNELLE EmmanuelPie Guiselin * Il arrive parfois que le temps politique s’accélère. Pour la Polynésie française, une page clef de l’histoire vient de s’écrire avec le retour au pouvoir de l’Union pour la démocratie (UPLD) et de son leader Oscar Temaru. Ce retour est intervenu à la faveur des élections partielles du 13 février 2005, moins de cinq mois après que le premier gouvernement Temaru ait été renversé par une motion de censure. Entre l’UPLD et le Tahoeraa Huiraatira, entre Oscar Temaru et Gaston Flosse, le cadre statutaire et le mode de scrutin ont constitué la toile de fond d’un combat plus profond mettant aux prises légalité et légitimité. Sometimes the political tempo of a country speeds up. In the case of French Polynesia, a major chapter in its history was written with the return to power of the Union for Democracy party (UPLD) and its leader Oscar Temaru. This came about as a result of the partial elections of 13 February 2005, that is less than 5 months after the first Temaru government had been ousted by a censure motion. Between UPLD and Tahoeraa Hiuraatira, between Oscar Temaru and Gaston Flosse, the legal framework and the voting system created the backdrop for a significant battle concerning legality and legitimacy. 27 février 2004, 7 mars 2005 1. Un peu plus de douze mois séparent ces deux dates, la première marquant la promulgation de la loi organique relative au nouveau statut d’autonomie de la Polynésie française 2, la seconde portant présentation du second gouvernement constitué par Oscar Temaru. -

Format Acrobat

N° 130 SÉNAT SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 2008-2009 Annexe au procès-verbal de la séance du 10 décembre 2008 RAPPORT D’INFORMATION FAIT au nom de la commission des Lois constitutionnelles, de législation, du suffrage universel, du Règlement et d'administration générale (1) à la suite d’une mission d’information effectuée en Polynésie française du 21 avril au 2 mai 2008, Par MM. Christian COINTAT et Bernard FRIMAT, Sénateurs. (1) Cette commission est composée de : M. Jean-Jacques Hyest, président ; M. Nicolas Alfonsi, Mme Nicole Borvo Cohen-Seat, MM. Patrice Gélard, Jean-René Lecerf, Jean-Claude Peyronnet, Jean-Pierre Sueur, Mme Catherine Troendle, M. François Zocchetto, vice-présidents ; MM. Laurent Béteille, Christian Cointat, Charles Gautier, Jacques Mahéas, secrétaires ; M. Alain Anziani, Mmes Éliane Assassi, Nicole Bonnefoy, Alima Boumediene-Thiery, MM. Elie Brun, François-Noël Buffet, Pierre-Yves Collombat, Jean-Patrick Courtois, Mme Marie-Hélène Des Esgaulx, M. Yves Détraigne, Mme Anne-Marie Escoffier, MM. Pierre Fauchon, Louis-Constant Fleming, Gaston Flosse, Christophe-André Frassa, Bernard Frimat, René Garrec, Jean-Claude Gaudin, Mmes Jacqueline Gourault, Virginie Klès, MM. Antoine Lefèvre, Dominique de Legge, Mme Josiane Mathon-Poinat, MM. Jacques Mézard, Jean-Pierre Michel, François Pillet, Hugues Portelli, Roland Povinelli, Bernard Saugey, Simon Sutour, Richard Tuheiava, Alex Türk, Jean-Pierre Vial, Jean-Paul Virapoullé, Richard Yung. - 3 - SOMMAIRE Pages EXAMEN EN COMMISSION..................................................................................................... -

2. Post-Colonial Political Institutions in the South Pacific Islands: a Survey

2. Post-Colonial Political Institutions in the South Pacific Islands: A Survey Jon Fraenkel Vue d’ensemble des Institutions politiques postcoloniales dans le Pacifique Sud insulaire A partir du milieu des années 80 et jusqu’à la fin des années 90, les nouveaux pays du Pacifique sortaient d’une période postcoloniale marquée au début par l’optimisme et dominée par une génération de dirigeants nationaux à la tête d’un régime autoritaire pour connaître par la suite une période marquée par les difficultés et l’instabilité et qui a connu le coup d’Etat de Fidji de 1987, la guerre civile à Bougainville, le conflit néo-calédonien et l’instabilité gouvernementale au Vanuatu et ailleurs. Dans les pays de la Mélanésie occidentale, cette instabilité a été exacerbée par des pressions exercées par des sociétés minières et des sociétés forestières étrangères. Cette étude retrace l’évolution et explore les complexités des diverses institutions politiques postcoloniales dans le Pacifique Sud à la fois au sein de ces institutions et dans leurs relations entre elles ; elle montre que les questions de science politique classique ont été abordées de façons extrêmement différentes dans la région. On y trouve une gamme de systèmes électoraux comprenant à la fois des régimes présidentiels et des régimes parlementaires ainsi que des situations de forte intégration d’un certain nombre de territoires au sein de puissances métropolitaines. Entre les deux extrêmes de l’indépendance totale et de l’intégration, les îles du Pacifique sont le lieu où l’on trouve un éventail d’arrangements politiques hybrides entre les territoires insulaires et les anciennes puissances coloniales. -

Political Reviews

Political Reviews Micronesia in Review: Issues and Events, 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 john r haglelgam, david w kupferman, kelly g marsh, samuel f mcphetres, donald r shuster, tyrone j taitano Polynesia in Review: Issues and Events, 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 lorenz gonschor, hapakuke pierre leleivai, margaret mutu, forrest wade young © 2012 by University of Hawai‘i Press 135 Polynesia in Review: Issues and Events, 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 Reviews of American Sëmoa, Cook claimed Tahoeraa to be an opposition Islands, Hawai‘i, Niue, Tokelau, party. During a budgetary debate on Tonga, and Tuvalu are not included in 2 August, Tahoeraa representatives this issue. charged Tong Sang with incompetency to lead the country and called on him French Polynesia to resign (tp, 2 Aug 2010). The period under review was not par- Tahoeraa’s confusing attitude of ticularly rich in new events. While no attacking the president and demand- economic recovery was in sight, local ing his resignation, while at the same politicians, fed by French subsidies, time allowing its members to keep continued their games of making and their cabinet portfolios, can only be unmaking majorities in the Assembly understood by looking at the pecu- of French Polynesia, culminating in liarities of French Polynesia’s political the eleventh change of government system. As long as Tong Sang did not since 2004. The only possibly inter- resign, he could only be overthrown esting development is that the new by a constructive vote of no confi- pro-independence majority now wants dence, which would require an overall to internationalize the country’s prob- majority and entail the automatic lems and get it out of the grip of Paris. -

RCT Le Vote Final Du Senat

NOTE N°29 : ADELS/UNADEL L’ultime lecture devant le Sénat à partir du texte de la Commission Mixte Paritaire ( 9 novembre 2010). Première partie Le vote final. Le Sénat a adopté définitivement le texte de la réforme des collectivités territoriales, le 9 novembre 2010, par 167 voix pour et 163 voix contre. Les 24 sénateurs communistes et apparentés ont voté contre. Sur les 17 sénateurs du Rassemblement Démocratique et Social Européen, 4 ont voté pour et 13 contre. Les 116 sénateurs socialistes ont voté contre. Les 29 sénateurs de l’Union Centriste se sont divisés : 14 ont voté pour, 6 ont voté contre (Didier Borotra, Marcel Deneux, Jean-Léonce Dupont, Jacqueline Gourault, Jean-Jacques Jégou et Jean-Marie Vanlerenberghe), 7 se sont abstenus (Jean Arthuis, Daniel Dubois, Françoise Féret, Pierre Jarlier, Hervé Maurey, Catherine Morin- Desailly et François Zoccheto). Les sénateurs UMP sont 149. 146 ont voté pour, 2 se sont abstenus (Sylvie Goy-Chavant et Louis Pinton), 1 n’a pas pris part au vote (Mireille Oudit). Sur les 7 non inscrits, 3 ont voté pour (Sylvie Desmurescaux, Gaston Flosse, Alex Türk), 4 ont voté contre. Le vote final de l’Assemblée Nationale aura lieu dans les jours qui viennent. Il n’est qu’une formalité, puisque les députés UMP sont majoritaires à eux seuls. Quelques extraits du débat général Jean-Patrick Courtois (rapporteur pour le Sénat de la Commission Mixte Paritaire). « Composé de trois volets principaux, ce texte vise respectivement à mettre en place des conseillers territoriaux, moyen d’améliorer la coordination entre départements et régions, sans remettre en cause les spécificités de chacune de ces collectivités territoriales, à améliorer le fonctionnement de l’intercommunalité et à clarifier les principes encadrant la répartition des compétences ». -

Sénateurs Département Email M

Sénateurs Département Email M. Jacques BERTHOU Ain [email protected] M. Rachel MAZUIR Ain [email protected] Mme Sylvie GOY-CHAVENT Ain [email protected] M. Antoine LEFÈVRE Aisne [email protected] M. Pierre ANDRÉ Aisne [email protected] M. Yves DAUDIGNY Aisne [email protected] M. Gérard DÉRIOT Allier [email protected] Mme Mireille SCHURCH Allier [email protected] M. Claude DOMEIZEL Alpes de Haute-Provence [email protected] M. Jean-Pierre LELEUX Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. Louis NÈGRE Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. Marc DAUNIS Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. René VESTRI Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] Mme Colette GIUDICELLI Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. Michel TESTON Ardèche [email protected] M. Yves CHASTAN Ardèche [email protected] M. Benoît HURÉ Ardennes [email protected] M. Marc LAMÉNIE Ardennes [email protected] M. Jean-Pierre BEL Ariège [email protected] M. Philippe ADNOT Aube [email protected] M. Yann GAILLARD Aube [email protected] M. Marcel RAINAUD Aude [email protected] M. Roland COURTEAU Aude [email protected] M. Stéphane MAZARS Aveyron [email protected] M. Alain FAUCONNIER Aveyron [email protected] M. André REICHARDT Bas-Rhin [email protected] M. Francis GRIGNON Bas-Rhin [email protected] M. Roland RIES Bas-Rhin [email protected] Mme Esther SITTLER Bas-Rhin [email protected] Mme Fabienne KELLER Bas-Rhin [email protected] M. -

Élections Sénatoriales

Lundi 29 septembre 2014 DIRECTION DE LA SÉANCE ÉLECTIONS SÉNATORIALES SCRUTIN DU 28 SEPTEMBRE 2014 SÉRIE 2 R É SUL TA TS OFFICIELS DU MINISTÈRE DE L’INTÉRIEUR 2 LISTE DES ABRÉVIATIONS UTILISÉES Nuances politiques individuelles des candidats LIBELLÉ SIGNIFICATION EXG Extrême gauche FG Front de gauche PG Parti de gauche COM Parti Communiste Français SOC Parti Socialiste RDG Parti Radical de Gauche DVG Divers gauche VEC Europe Ecologie Les Verts ECO Ecologiste REG Régionaliste DIV Divers MDM Mouvement démocrate UDI Union des démocrates et indépendants UMP Union pour un Mouvement Populaire DLR Debout la République DVD Divers droite FN Front National EXD Extrême droite 3 LISTE DES ABRÉVIATIONS UTILISÉES Nuances politiques des listes LIBELLÉ SIGNIFICATION LEXG Liste d'extrême gauche LFG Liste présentée par le Front de gauche LCOM Liste présentée par le PCF, hors Front de gauche LPG Liste du Parti de gauche, hors Front de gauche LSOC Liste du Parti Socialiste LVEC Liste présentée par Europe Ecologie Les Verts LRDG Liste présentée par le Parti Radical de Gauche LDVG Liste divers gauche LUG Liste d'union de la gauche LDIV Autre liste LREG Liste régionaliste LMDM Liste présentée par le MoDem LUDI Liste présentée par l'UDI LCEN Liste d'union du centre LUD Liste d'union de la droite et du centre LUMP Liste de l'UMP LDLR Liste Debout la République LDVD Liste divers droite LFN Liste du Front National LEXD Liste d'extrême droite 4 I. – FRANCE MÉTROPOLITAINE 5 01 - AIN Sénateurs sortants : 3 3 sièges à pourvoir M. Jacques BERTHOU (App. Soc.) Représentation proportionnelle Mme Sylvie GOY-CHAVENT (UDI-UC) M. -

Multilingualism in French Polynesia: Past and Future

Section VI Multilingualism in French Polynesia: Past and future Multilingualism is in its very essence unstable, as it make it possible to perceive major tendencies for involves living languages whose dynamics depend the next 20 to 30 years, with regard to multi- above all on extra-linguistic factors. This funda- lingualism in French Polynesia. The future of lan- mental instability renders virtually impossible any guages in the country as a whole can only be un- prediction beyond two generations. derstood through an analysis archipelago-by- However, the six years of field research that archipelago, and language-by-language. As we will Jean-Michel Charpentier has just carried out in see, knowledge of the recent history of each region French Polynesia in over twenty different locations will enable us to draw up their future perspectives. The Marquesas In the Marquesas Islands, Marquesan remains the As for the third island, Ua Huka, it was essen- daily language for the majority of islanders. The tially depopulated in the 19th century, before being existence of two dialects, with their lexical and repopulated by both northern and southern Mar- phonetic specificities for each island, does not quesans. This is why the island itself is known un- hinder this fundamental linguistic unity. der two different names, Ua Huka (with a /k/ The 2012 census (ISPF 2012) gave a population typical of the northern dialect) and Ua Huna (with of 9,261 for the archipelago, among which two an /n/ typical of southern Marquesan).63 thirds lived in the Northern Marquesas (Nuku Hiva 2,967; Ua Pou 2,175; Ua Huka 621), and one third The island of Hiva Oa, in southern Marquesas, (3,498 inhabitants) lived in the southern part. -

Au Cœur De L'océan Mon Pays

IOTA PRODUCTION PRÉSENTE | PRESENTS MA’OHI NUI AU CŒUR DE L’OCÉAN MON PAYS IN THE HEART OF THE OCEAN MY COUNTRY LIES UN FILM DE | A FILM BY ANNICK GHIJZELINGS PRESSKIT Tahiti, French Polynesia. Between the runway of the International airport and a small mound of earth lies a district called the Flamboyant. Over there, one says "district" as not to say "shantytown". French colonial history and thirty years of nuclear tests have filled these districts with an alienated and « SOMETHING SURVIVES, tired people. Like the radioactivity that one cannot feel or see, SOMETHING TENUOUS, HIDDEN, but that persists for hundreds of thousands of years, the ALMOST INVISIBLE, WHICH RESISTS ERASURE » contamination of minds has slowly and permanently installed itself. Today the Ma'ohi people are a subordinate people who have forgotten their language, ignored their history and have lost their connection to their land and their relationship to the world. Yet within this neighbourhood of coloured sheds, something survives, something tenuous, hidden, almost invisible, which resists erasure. By confronting the Ma'ohi spirit with its history of nuclear tests and its fractured existence, the film shows the face of contemporary colonisation and the vital impetus of a people trying not to forget themselves and who, silently, are seeking the path of independence. ! 1 CONTEXT FRENCH POLYNESIA Located in the South Pacific, 20.000 kilometres away from Paris, French Polynesia is an overseas territory of the French Republic. It is composed of 118 islands of which only 67 are inhabited. Despite the relative autonomy granted by France, a large number of institutions remain under the supervision of the French State: justice, army, education and health. -

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics

France in the South Pacific Power and Politics France in the South Pacific Power and Politics Denise Fisher Published by ANU E Press The Australian National University Canberra ACT 0200, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://epress.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Fisher, Denise, author. Title: France in the South Pacific : power and politics / Denise Fisher. ISBN: 9781922144942 (paperback) 9781922144959 (eBook) Notes: Includes bibliographical references. Subjects: France--Foreign relations--Oceania. Oceania--Foreign relations--France. France--Foreign relations--New Caledonia. New Caledonia--Foreign relations--France. Dewey Number: 327.44095 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU E Press Printed by Griffin Press This edition © 2013 ANU E Press Contents Acknowledgements . vii List of maps, figures and tables . ix Glossary and acronyms . xi Maps . xix Introduction . 1 Part I — France in the Pacific to the 1990s 1. The French Pacific presence to World War II . 13 2. France manages independence demands and nuclear testing 1945–1990s . 47 3 . Regional diplomatic offensive 1980s–1990s . 89 Part II — France in the Pacific: 1990s to present 4. New Caledonia: Implementation of the Noumea Accord and political evolution from 1998 . 99 5. French Polynesia: Autonomy or independence? . 179 6. France’s engagement in the region from the 1990s: France, its collectivities, the European Union and the region . -

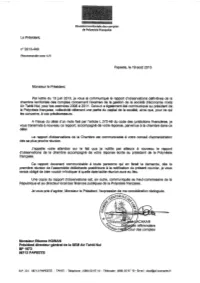

Rapport De La CTC ATN.Pdf

RAPPORT D’OBSERVATIONS DEFINITIVES SEML AIR TAHITI NUI Exercices 2008 à 2011 RAPPEL DE LA PROCEDURE Dans le cadre de son programme de travail pour 2012, la chambre territoriale des comptes de la Polynésie française a procédé à l’examen de la gestion de la société d’économie mixte Air Tahiti Nui sur les exercices 2008 à 2011. Après avoir recueilli l’avis du Ministère Public près la chambre sur sa compétence pour le contrôle de la société, le président de la chambre territoriale des comptes de Polynésie française a informé, par lettre du 12 avril 2012, de l’ouverture du contrôle le président de la société en fonctions, M. Etienne HOWAN, et ses prédécesseurs, MM. Cédric PASTOUR, Michel RISPAL, Christian VERNAUDON, et Geffry SALMON. L’entretien préalable facultatif prévu par l’article L.272-46 du code des juridictions financières a eu lieu le 20 novembre 2012 avec M. Etienne HOWAN, le 26 octobre 2012 avec M. Michel RISPAL, le 14 novembre 2012 avec M. Geffry SALMON, et le 22 novembre avec MM. Christian VERNAUDON et Cédric PASTOUR. Lors de sa séance du 17 janvier 2013, la chambre avait décidé l’envoi d’un rapport d’observations provisoires. Le 7 février 2013, le rapport a été notifié aux dirigeants successifs de la société, MM. Etienne HOWAN, Michel RISPAL, Geffry SALMON, Christian VERNAUDON, Cédric PASTOUR, et à M. Oscar TEMARU, président de la Polynésie française en fonctions. Après avoir examiné les réponses écrites produites par MM. Etienne HOWAN et Oscar, TEMARU, la Chambre, lors de sa séance du 31 mai 2013, a arrêté ses observations définitives reproduites ci-après.