Power Switching and Renewal in French Polynesian Politics 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Répartition De La Population En Polynésie Française En 2017

Répartition de la population en Polynésie française en 2017 PIRAE ARUE Paopao Teavaro Hatiheu PAPEETE Papetoai A r c h MAHINA i p e l d FAA'A HITIAA O TE RA e s NUKU HIVA M a UA HUKA r q PUNAAUIA u HIVA OA i TAIARAPU-EST UA POU s Taiohae Taipivai e PAEA TA HUATA s NUKU HIVA Haapiti Afareaitu FATU HIVA Atuona PAPARA TEVA I UTA MOO REA TAIARAPU-OUEST A r c h i p e l d Puamau TAHITI e s T MANIHI u a HIVA OA Hipu RA NGIROA m Iripau TA KAROA PUKA P UKA o NA PUKA Hakahau Faaaha t u Tapuamu d e l a S o c i é MAKEMO FANGATA U - p e l t é h i BORA BORA G c a Haamene r MAUPITI Ruutia A TA HA A ARUTUA m HUAHINE FAKARAVA b TATAKOTO i Niua Vaitoare RAIATEA e TAHITI r TAHAA ANAA RE AO Hakamaii MOORE A - HIK UE RU Fare Maeva MAIAO UA POU Faie HA O NUKUTAVAKE Fitii Apataki Tefarerii Maroe TUREIA Haapu Parea RIMATARA RURUTU A r c h Arutua HUAHINE i p e TUBUAI l d e s GAMBIE R Faanui Anau RA IVAVAE A u s Kaukura t r Nombre a l AR UTUA d'individus e s Taahuaia Moerai Mataura Nunue 20 000 Mataiva RA PA BOR A B OR A 10 000 Avera Tikehau 7 000 Rangiroa Hauti 3 500 Mahu Makatea 1 000 RURUT U TUBUAI RANGIROA ´ 0 110 Km So u r c e : Re c en se m en t d e la p o p u la ti o n 2 0 1 7 - IS P F -I N SE E Répartition de la population aux Îles Du Vent en 2017 TAHITI MAHINA Paopao Papetoai ARUE PAPEETE PIRAE HITIAA O TE RA FAAA Teavaro Tiarei Mahaena Haapiti PUNAAUIA Afareaitu Hitiaa Papenoo MOOREA 0 2 Km Faaone PAEA Papeari TAIARAPU-EST Mataiea Afaahiti Pueu Toahotu Nombre PAPARA d'individus TEVA I UTA Tautira 20 000 Vairao 15 000 13 000 Teahupoo 10 000 TAIARAPU-OUEST -

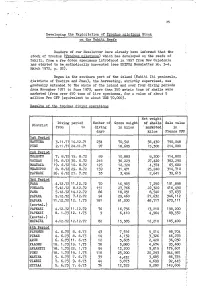

Developing the Exploitation of <I>Trochus Niloticus</I> Stock on the Tahiti Reefs

35 Developing the Exploitation of Trochu3 niloticus Stock onithe_Ta'hiti Reefs Readers of our Newsletter have already been informed that the stock of trochus (Trochug niloticus) which has developed on the reefs of Tahiti, from a few dozen specimens introduced in 1957 from Hew Caledonia has started to be methodically harvested (see SPIPDA Newsletter ITo. 3-4, March 1972, p. 32). Begun in the southern part of the island (Tahiti Iti peninsula, districts of Tautira and Pueu), the harvesting, strictly supervised, was gradually extended to the whole of the island and over four diving periods fjrom November 1971 to June 1973? more than 350 metric tons of shells were marketed (from over 450 tons of live specimens, for a value of about 5 million Frs CTP (equivalent to about US$ 70,000). Results of .the trochus. diving operations Net weight Diving period Number of Gross weight of shells Sale value District from to diving in kilos ' marketed in days kilos Francs CPP 1st Period TAUTIRA 3-11.71 I4.l2.7i 234 70,541 56,430 790,048 .. PUEU 2.11 .71 24.11.71 97 18,605 ... 15,300 214,000 2nd Period TOAHOTU 7. 8.72 15. 8,72 89 10r883 8,200 114,800 : VAIRAO 15. 8.72 30. 8.72 216 36J229 27,420 362,290 , MAATAIA. 19. 6.72 10. 8o72 125 12,724 4,374 65,600 TEAHUPOO 8. 8.72 29. 8.72 159 31,471 25,240' 314,710 PAPEARI 26. 6.72 27. 7.72 35 3,456 2,641 39,615 ; 3rd Period FAAA 4.12,72 11.12.72 70 16,983 7,250 101,898 PIMAAUA 5.12.72 8,12.72 151 27,766 .22,320 416,490 PAEA 5.12.72 14*12.72 86 18,051 8, 540 97,633 PAPARA 5.12.72 7.12.72 94 29,460 21,632 346,112 PAPARA 11.12.72 12. -

Sénat Proposition De Résolution

N° 428 SÉNAT SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 2008-2009 Annexe au procès-verbal de la séance du 20 mai 2009 PROPOSITION DE RÉSOLUTION tendant à modifier le Règlement du Sénat pour mettre en œuvre la révision constitutionnelle, conforter le pluralisme sénatorial et rénover les méthodes de travail du Sénat, TEXTE DE LA COMMISSION DES LOIS CONSTITUTIONNELLES, DE LÉGISLATION, DU SUFFRAGE UNIVERSEL, DU RÈGLEMENT ET D’ADMINISTRATION GÉNÉRALE (1), (1) Cette commission est composée de : M. Jean-Jacques Hyest, président ; M. Nicolas Alfonsi, Mme Nicole Borvo Cohen-Seat, MM. Patrice Gélard, Jean-René Lecerf, Jean-Claude Peyronnet, Jean-Pierre Sueur, Mme Catherine Troendle, M. François Zocchetto, vice-présidents ; MM. Laurent Béteille, Christian Cointat, Charles Gautier, Jacques Mahéas, secrétaires ; M. Alain Anziani, Mmes Éliane Assassi, Nicole Bonnefoy, Alima Boumediene-Thiery, MM. Elie Brun, François-Noël Buffet, Pierre-Yves Collombat, Jean-Patrick Courtois, Mme Marie-Hélène Des Esgaulx, M. Yves Détraigne, Mme Anne-Marie Escoffier, MM. Pierre Fauchon, Louis-Constant Fleming, Gaston Flosse, Christophe-André Frassa, Bernard Frimat, René Garrec, Jean-Claude Gaudin, Mmes Jacqueline Gourault, Virginie Klès, MM. Antoine Lefèvre, Dominique de Legge, Mme Josiane Mathon-Poinat, MM. Jacques Mézard, Jean-Pierre Michel, François Pillet, Hugues Portelli, Roland Povinelli, Bernard Saugey, Simon Sutour, Richard Tuheiava, Alex Türk, Jean-Pierre Vial, Jean-Paul Virapoullé, Richard Yung. Voir le(s) numéro(s) : Sénat : 377 et 427 (2008-2009) - 3 - PROPOSITION DE RÉSOLUTION TENDANT À MODIFIER LE RÈGLEMENT DU SÉNAT POUR METTRE EN ŒUVRE LA RÉVISION CONSTITUTIONNELLE, CONFORTER LE PLURALISME SÉNATORIAL ET RÉNOVER LES MÉTHODES DE TRAVAIL DU SÉNAT Article 1er Composition du Bureau du Sénat I. -

Du Premier Au Second Gouvernement Temaru: Une Annee De Crise Politique Et Institutionnelle

1 DU PREMIER AU SECOND GOUVERNEMENT TEMARU: UNE ANNEE DE CRISE POLITIQUE ET INSTITUTIONNELLE EmmanuelPie Guiselin * Il arrive parfois que le temps politique s’accélère. Pour la Polynésie française, une page clef de l’histoire vient de s’écrire avec le retour au pouvoir de l’Union pour la démocratie (UPLD) et de son leader Oscar Temaru. Ce retour est intervenu à la faveur des élections partielles du 13 février 2005, moins de cinq mois après que le premier gouvernement Temaru ait été renversé par une motion de censure. Entre l’UPLD et le Tahoeraa Huiraatira, entre Oscar Temaru et Gaston Flosse, le cadre statutaire et le mode de scrutin ont constitué la toile de fond d’un combat plus profond mettant aux prises légalité et légitimité. Sometimes the political tempo of a country speeds up. In the case of French Polynesia, a major chapter in its history was written with the return to power of the Union for Democracy party (UPLD) and its leader Oscar Temaru. This came about as a result of the partial elections of 13 February 2005, that is less than 5 months after the first Temaru government had been ousted by a censure motion. Between UPLD and Tahoeraa Hiuraatira, between Oscar Temaru and Gaston Flosse, the legal framework and the voting system created the backdrop for a significant battle concerning legality and legitimacy. 27 février 2004, 7 mars 2005 1. Un peu plus de douze mois séparent ces deux dates, la première marquant la promulgation de la loi organique relative au nouveau statut d’autonomie de la Polynésie française 2, la seconde portant présentation du second gouvernement constitué par Oscar Temaru. -

Format Acrobat

N° 130 SÉNAT SESSION ORDINAIRE DE 2008-2009 Annexe au procès-verbal de la séance du 10 décembre 2008 RAPPORT D’INFORMATION FAIT au nom de la commission des Lois constitutionnelles, de législation, du suffrage universel, du Règlement et d'administration générale (1) à la suite d’une mission d’information effectuée en Polynésie française du 21 avril au 2 mai 2008, Par MM. Christian COINTAT et Bernard FRIMAT, Sénateurs. (1) Cette commission est composée de : M. Jean-Jacques Hyest, président ; M. Nicolas Alfonsi, Mme Nicole Borvo Cohen-Seat, MM. Patrice Gélard, Jean-René Lecerf, Jean-Claude Peyronnet, Jean-Pierre Sueur, Mme Catherine Troendle, M. François Zocchetto, vice-présidents ; MM. Laurent Béteille, Christian Cointat, Charles Gautier, Jacques Mahéas, secrétaires ; M. Alain Anziani, Mmes Éliane Assassi, Nicole Bonnefoy, Alima Boumediene-Thiery, MM. Elie Brun, François-Noël Buffet, Pierre-Yves Collombat, Jean-Patrick Courtois, Mme Marie-Hélène Des Esgaulx, M. Yves Détraigne, Mme Anne-Marie Escoffier, MM. Pierre Fauchon, Louis-Constant Fleming, Gaston Flosse, Christophe-André Frassa, Bernard Frimat, René Garrec, Jean-Claude Gaudin, Mmes Jacqueline Gourault, Virginie Klès, MM. Antoine Lefèvre, Dominique de Legge, Mme Josiane Mathon-Poinat, MM. Jacques Mézard, Jean-Pierre Michel, François Pillet, Hugues Portelli, Roland Povinelli, Bernard Saugey, Simon Sutour, Richard Tuheiava, Alex Türk, Jean-Pierre Vial, Jean-Paul Virapoullé, Richard Yung. - 3 - SOMMAIRE Pages EXAMEN EN COMMISSION..................................................................................................... -

2. Post-Colonial Political Institutions in the South Pacific Islands: a Survey

2. Post-Colonial Political Institutions in the South Pacific Islands: A Survey Jon Fraenkel Vue d’ensemble des Institutions politiques postcoloniales dans le Pacifique Sud insulaire A partir du milieu des années 80 et jusqu’à la fin des années 90, les nouveaux pays du Pacifique sortaient d’une période postcoloniale marquée au début par l’optimisme et dominée par une génération de dirigeants nationaux à la tête d’un régime autoritaire pour connaître par la suite une période marquée par les difficultés et l’instabilité et qui a connu le coup d’Etat de Fidji de 1987, la guerre civile à Bougainville, le conflit néo-calédonien et l’instabilité gouvernementale au Vanuatu et ailleurs. Dans les pays de la Mélanésie occidentale, cette instabilité a été exacerbée par des pressions exercées par des sociétés minières et des sociétés forestières étrangères. Cette étude retrace l’évolution et explore les complexités des diverses institutions politiques postcoloniales dans le Pacifique Sud à la fois au sein de ces institutions et dans leurs relations entre elles ; elle montre que les questions de science politique classique ont été abordées de façons extrêmement différentes dans la région. On y trouve une gamme de systèmes électoraux comprenant à la fois des régimes présidentiels et des régimes parlementaires ainsi que des situations de forte intégration d’un certain nombre de territoires au sein de puissances métropolitaines. Entre les deux extrêmes de l’indépendance totale et de l’intégration, les îles du Pacifique sont le lieu où l’on trouve un éventail d’arrangements politiques hybrides entre les territoires insulaires et les anciennes puissances coloniales. -

Political Reviews

Political Reviews Micronesia in Review: Issues and Events, 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 john r haglelgam, david w kupferman, kelly g marsh, samuel f mcphetres, donald r shuster, tyrone j taitano Polynesia in Review: Issues and Events, 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 lorenz gonschor, hapakuke pierre leleivai, margaret mutu, forrest wade young © 2012 by University of Hawai‘i Press 135 Polynesia in Review: Issues and Events, 1 July 2010 to 30 June 2011 Reviews of American Sëmoa, Cook claimed Tahoeraa to be an opposition Islands, Hawai‘i, Niue, Tokelau, party. During a budgetary debate on Tonga, and Tuvalu are not included in 2 August, Tahoeraa representatives this issue. charged Tong Sang with incompetency to lead the country and called on him French Polynesia to resign (tp, 2 Aug 2010). The period under review was not par- Tahoeraa’s confusing attitude of ticularly rich in new events. While no attacking the president and demand- economic recovery was in sight, local ing his resignation, while at the same politicians, fed by French subsidies, time allowing its members to keep continued their games of making and their cabinet portfolios, can only be unmaking majorities in the Assembly understood by looking at the pecu- of French Polynesia, culminating in liarities of French Polynesia’s political the eleventh change of government system. As long as Tong Sang did not since 2004. The only possibly inter- resign, he could only be overthrown esting development is that the new by a constructive vote of no confi- pro-independence majority now wants dence, which would require an overall to internationalize the country’s prob- majority and entail the automatic lems and get it out of the grip of Paris. -

Bioerosion of Experimental Substrates on High Islands and on Atoll Lagoons (French Polynesia) After Two Years of Exposure

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 166: 119-130,1998 Published May 28 Mar Ecol Prog Ser -- l Bioerosion of experimental substrates on high islands and on atoll lagoons (French Polynesia) after two years of exposure 'Centre d'oceanologie de Marseille, UMR CNRS 6540, Universite de la Mediterranee, Station Marine d'Endoume, rue de la Batterie des Lions, F-13007 Marseille, France 2Centre de Sedimentologie et Paleontologie. UPRESA CNRS 6019. Universite de Provence, Aix-Marseille I, case 67, F-13331 Marseille cedex 03. France 3The Australian Museum, 6-8 College Street, 2000 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia "epartment of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA ABSTRACT: Rates of bioerosion by grazing and boring were studied in lagoons of 2 high islands (3 sites) and 2 atolls (2 sites each) In French Polynesia using experimental carbonate substrates (blocks of Porites lutea skeleton). The substrate loss versus accretion was measured after 6 and 24 mo of exposure. The results show significant differences between pristine environments on atolls and envi- ronments on high islands sub!ected to different levels of eutrophication and pollution due to human activities. Whereas experimental substrates on the atolls maintain a balance between accretion and erosion or exhibit net gains from accretion (positive budget), only 1 site on a high island exhibits sig- nificant loss of substrate by net erosion (negative budget). The erosional patterns set within the first 6 rno of exposure were largely maintained throughout the entire duration of the expeiiment. The inten- sity of bioerosion by grazing increases dramatically when reefs are exposed to pollution from harbour waters; this is shown at one of the Tahiti sites, where the highest average bioerosional loss, up to 25 kg m-2 yr-' (6.9 kg m-' yr-I on a single isolated block), of carbonate substrate was recorded. -

RCT Le Vote Final Du Senat

NOTE N°29 : ADELS/UNADEL L’ultime lecture devant le Sénat à partir du texte de la Commission Mixte Paritaire ( 9 novembre 2010). Première partie Le vote final. Le Sénat a adopté définitivement le texte de la réforme des collectivités territoriales, le 9 novembre 2010, par 167 voix pour et 163 voix contre. Les 24 sénateurs communistes et apparentés ont voté contre. Sur les 17 sénateurs du Rassemblement Démocratique et Social Européen, 4 ont voté pour et 13 contre. Les 116 sénateurs socialistes ont voté contre. Les 29 sénateurs de l’Union Centriste se sont divisés : 14 ont voté pour, 6 ont voté contre (Didier Borotra, Marcel Deneux, Jean-Léonce Dupont, Jacqueline Gourault, Jean-Jacques Jégou et Jean-Marie Vanlerenberghe), 7 se sont abstenus (Jean Arthuis, Daniel Dubois, Françoise Féret, Pierre Jarlier, Hervé Maurey, Catherine Morin- Desailly et François Zoccheto). Les sénateurs UMP sont 149. 146 ont voté pour, 2 se sont abstenus (Sylvie Goy-Chavant et Louis Pinton), 1 n’a pas pris part au vote (Mireille Oudit). Sur les 7 non inscrits, 3 ont voté pour (Sylvie Desmurescaux, Gaston Flosse, Alex Türk), 4 ont voté contre. Le vote final de l’Assemblée Nationale aura lieu dans les jours qui viennent. Il n’est qu’une formalité, puisque les députés UMP sont majoritaires à eux seuls. Quelques extraits du débat général Jean-Patrick Courtois (rapporteur pour le Sénat de la Commission Mixte Paritaire). « Composé de trois volets principaux, ce texte vise respectivement à mettre en place des conseillers territoriaux, moyen d’améliorer la coordination entre départements et régions, sans remettre en cause les spécificités de chacune de ces collectivités territoriales, à améliorer le fonctionnement de l’intercommunalité et à clarifier les principes encadrant la répartition des compétences ». -

Liste Des Labellisés CLCE Au 30 Novembre 2017 Arue Faaa

Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 TAHITI Arue ➢ DOMOTEC Contact : CHOUGUES Gilles 87 78 15 35 40 45 34 07 [email protected] Courrier : BP 14717 – 98701 ARUE Faaa 1 ➢ 987 ELEC Contact : WATANABE Otis 87 78 43 22 : 40 82 30 71 [email protected] Courrier : BP 61609 – 98702FAA’A ➢ ARESO Contact : MOUSSET Laurent 87 70 73 42 [email protected] Courrier : BP 61781 – 98704 FAA’A Centre ➢ ELEC 220 Contact : HERLEMME Mickael 87 74 73 09 [email protected] Courrier : BP 3341 – 98717 Punaauia Association Centre Label et Contrôle Electrique Téléphone : 40 47 27 72 Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 ➢ TEARATAI UIRA Contact : KONG YEK FHAN Christian 87 72 59 21 [email protected] Courrier : BP 6129 – 98704 FAA’A ➢ TECHNO FROID Contact : LANVIN Jérôme 40 80 04 05 40 80 04 09 [email protected] Courrier : BP 50354 – 98716 PIRAE Contact : TEHURITAUA Marc ➢ TEHURITAUA & FILS 2 87 77 36 21 [email protected] Courrier : BP 6276 – 98702 FAA’A Mahina ➢ A.E.S ELECTRICITE Contact : MICHON Nicolas 87 34 34 87 [email protected] Courrier : BP 90124 Motu Uta – 98715 Papeete ➢ POLY RESEAUX CONCEPT Contact : OPUTU John 87 34 63 24 [email protected] Association Centre Label et Contrôle Electrique Téléphone : 40 47 27 72 Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 Paea ➢ ELECTRICITE ET RESEAUX DE Contact : LALANDEC Patrick TAHITI (ERDT) 87 77 09 83 / 87 78 75 31 40 50 79 41 [email protected] Courrier : BP 50131 – 98716 PIRAE ➢ WES ELEC Contact : BUTSCHER Wesley 89 72 78 31 / 87 75 08 15 40 81 34 66 [email protected] / [email protected] -

Sénateurs Département Email M

Sénateurs Département Email M. Jacques BERTHOU Ain [email protected] M. Rachel MAZUIR Ain [email protected] Mme Sylvie GOY-CHAVENT Ain [email protected] M. Antoine LEFÈVRE Aisne [email protected] M. Pierre ANDRÉ Aisne [email protected] M. Yves DAUDIGNY Aisne [email protected] M. Gérard DÉRIOT Allier [email protected] Mme Mireille SCHURCH Allier [email protected] M. Claude DOMEIZEL Alpes de Haute-Provence [email protected] M. Jean-Pierre LELEUX Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. Louis NÈGRE Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. Marc DAUNIS Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. René VESTRI Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] Mme Colette GIUDICELLI Alpes-Maritimes [email protected] M. Michel TESTON Ardèche [email protected] M. Yves CHASTAN Ardèche [email protected] M. Benoît HURÉ Ardennes [email protected] M. Marc LAMÉNIE Ardennes [email protected] M. Jean-Pierre BEL Ariège [email protected] M. Philippe ADNOT Aube [email protected] M. Yann GAILLARD Aube [email protected] M. Marcel RAINAUD Aude [email protected] M. Roland COURTEAU Aude [email protected] M. Stéphane MAZARS Aveyron [email protected] M. Alain FAUCONNIER Aveyron [email protected] M. André REICHARDT Bas-Rhin [email protected] M. Francis GRIGNON Bas-Rhin [email protected] M. Roland RIES Bas-Rhin [email protected] Mme Esther SITTLER Bas-Rhin [email protected] Mme Fabienne KELLER Bas-Rhin [email protected] M. -

General Assembly Distr.: General 8 January 2021 English Original: French

United Nations A/AC.109/2021/7 General Assembly Distr.: General 8 January 2021 English Original: French Special Committee on the Situation with regard to the Implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples French Polynesia Working paper prepared by the Secretariat Contents Page The Territory at a glance ......................................................... 3 I. Constitutional, political and legal issues ............................................ 5 II. Economic conditions ............................................................ 8 A. General ................................................................... 8 B. Agriculture, pearl farming, fisheries and aquaculture ............................. 9 C. Industry .................................................................. 9 D. Transport and communications ............................................... 10 E. Tourism .................................................................. 10 F. Environment .............................................................. 10 III. Social conditions ............................................................... 11 A. General ................................................................... 11 B. Employment .............................................................. 11 C. Education ................................................................. 12 D. Health care ................................................................ 12 IV. Relations with international organizations and