Bioerosion of Experimental Substrates on High Islands and on Atoll Lagoons (French Polynesia) After Two Years of Exposure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Répartition De La Population En Polynésie Française En 2017

Répartition de la population en Polynésie française en 2017 PIRAE ARUE Paopao Teavaro Hatiheu PAPEETE Papetoai A r c h MAHINA i p e l d FAA'A HITIAA O TE RA e s NUKU HIVA M a UA HUKA r q PUNAAUIA u HIVA OA i TAIARAPU-EST UA POU s Taiohae Taipivai e PAEA TA HUATA s NUKU HIVA Haapiti Afareaitu FATU HIVA Atuona PAPARA TEVA I UTA MOO REA TAIARAPU-OUEST A r c h i p e l d Puamau TAHITI e s T MANIHI u a HIVA OA Hipu RA NGIROA m Iripau TA KAROA PUKA P UKA o NA PUKA Hakahau Faaaha t u Tapuamu d e l a S o c i é MAKEMO FANGATA U - p e l t é h i BORA BORA G c a Haamene r MAUPITI Ruutia A TA HA A ARUTUA m HUAHINE FAKARAVA b TATAKOTO i Niua Vaitoare RAIATEA e TAHITI r TAHAA ANAA RE AO Hakamaii MOORE A - HIK UE RU Fare Maeva MAIAO UA POU Faie HA O NUKUTAVAKE Fitii Apataki Tefarerii Maroe TUREIA Haapu Parea RIMATARA RURUTU A r c h Arutua HUAHINE i p e TUBUAI l d e s GAMBIE R Faanui Anau RA IVAVAE A u s Kaukura t r Nombre a l AR UTUA d'individus e s Taahuaia Moerai Mataura Nunue 20 000 Mataiva RA PA BOR A B OR A 10 000 Avera Tikehau 7 000 Rangiroa Hauti 3 500 Mahu Makatea 1 000 RURUT U TUBUAI RANGIROA ´ 0 110 Km So u r c e : Re c en se m en t d e la p o p u la ti o n 2 0 1 7 - IS P F -I N SE E Répartition de la population aux Îles Du Vent en 2017 TAHITI MAHINA Paopao Papetoai ARUE PAPEETE PIRAE HITIAA O TE RA FAAA Teavaro Tiarei Mahaena Haapiti PUNAAUIA Afareaitu Hitiaa Papenoo MOOREA 0 2 Km Faaone PAEA Papeari TAIARAPU-EST Mataiea Afaahiti Pueu Toahotu Nombre PAPARA d'individus TEVA I UTA Tautira 20 000 Vairao 15 000 13 000 Teahupoo 10 000 TAIARAPU-OUEST -

How Do Upwelling and El Niño Impact Coral Reef Growth? a Guided, Inquiry-Based Lesson

OceTHE OFFICIALa MAGAZINEn ogOF THE OCEANOGRAPHYra SOCIETYphy CITATION Gravinese, P.M., L.T. Toth, C.J. Randall, and R.B. Aronson. 2018. How do upwelling and El Niño impact coral reef growth? A guided, inquiry-based lesson. Oceanography 31(4):184–188, https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2018.424. DOI https://doi.org/10.5670/oceanog.2018.424 PERMISSIONS Oceanography (ISSN 1042-8275) is published by The Oceanography Society, 1 Research Court, Suite 450, Rockville, MD 20850 USA. ©2018 The Oceanography Society, Inc. Permission is granted for individuals to read, download, copy, distribute, print, search, and link to the full texts of Oceanography articles. Figures, tables, and short quotes from the magazine may be republished in scientific books and journals, on websites, and in PhD dissertations at no charge, but the materi- als must be cited appropriately (e.g., authors, Oceanography, volume number, issue number, page number[s], figure number[s], and DOI for the article). Republication, systemic reproduction, or collective redistribution of any material in Oceanography is permitted only with the approval of The Oceanography Society. Please contact Jennifer Ramarui at [email protected]. Permission is granted to authors to post their final pdfs, provided byOceanography , on their personal or institutional websites, to deposit those files in their institutional archives, and to share the pdfs on open-access research sharing sites such as ResearchGate and Academia.edu. DOWNLOADED FROM HTTPS://TOS.ORG/OCEANOGRAPHY HANDS-ON OCEANOGRAPHY How Do Upwelling and El Niño Impact Coral Reef Growth? A GUIDED, INQUIRY-BASED LESSON By Philip M. Gravinese, Lauren T. Toth, Carly J. -

The Roles of Endolithic Fungi in Bioerosion and Disease in Marine Ecosystems. II. Potential Facultatively Parasitic Anamorphic A

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Dundee Online Publications University of Dundee The roles of endolithic fungi in bioerosion and disease in marine ecosystems. II. Potential facultatively parasitic anamorphic ascomycetes can cause disease in corals and molluscs Gleason, Frank H.; Gadd, Geoffrey M.; Pitt, John I.; Larkum, Anthony W.D. Published in: Mycology DOI: 10.1080/21501203.2017.1371802 Publication date: 2017 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Gleason, F. H., Gadd, G. M., Pitt, J. I., & Larkum, A. W. D. (2017). The roles of endolithic fungi in bioerosion and disease in marine ecosystems. II. Potential facultatively parasitic anamorphic ascomycetes can cause disease in corals and molluscs. Mycology, 8(3), 216-227. https://doi.org/10.1080/21501203.2017.1371802 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Mycology An International Journal on Fungal Biology ISSN: 2150-1203 (Print) 2150-1211 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tmyc20 The roles of endolithic fungi in bioerosion and disease in marine ecosystems. -

Developing the Exploitation of <I>Trochus Niloticus</I> Stock on the Tahiti Reefs

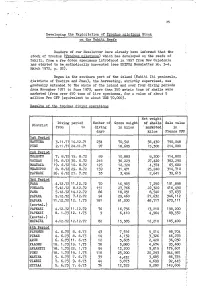

35 Developing the Exploitation of Trochu3 niloticus Stock onithe_Ta'hiti Reefs Readers of our Newsletter have already been informed that the stock of trochus (Trochug niloticus) which has developed on the reefs of Tahiti, from a few dozen specimens introduced in 1957 from Hew Caledonia has started to be methodically harvested (see SPIPDA Newsletter ITo. 3-4, March 1972, p. 32). Begun in the southern part of the island (Tahiti Iti peninsula, districts of Tautira and Pueu), the harvesting, strictly supervised, was gradually extended to the whole of the island and over four diving periods fjrom November 1971 to June 1973? more than 350 metric tons of shells were marketed (from over 450 tons of live specimens, for a value of about 5 million Frs CTP (equivalent to about US$ 70,000). Results of .the trochus. diving operations Net weight Diving period Number of Gross weight of shells Sale value District from to diving in kilos ' marketed in days kilos Francs CPP 1st Period TAUTIRA 3-11.71 I4.l2.7i 234 70,541 56,430 790,048 .. PUEU 2.11 .71 24.11.71 97 18,605 ... 15,300 214,000 2nd Period TOAHOTU 7. 8.72 15. 8,72 89 10r883 8,200 114,800 : VAIRAO 15. 8.72 30. 8.72 216 36J229 27,420 362,290 , MAATAIA. 19. 6.72 10. 8o72 125 12,724 4,374 65,600 TEAHUPOO 8. 8.72 29. 8.72 159 31,471 25,240' 314,710 PAPEARI 26. 6.72 27. 7.72 35 3,456 2,641 39,615 ; 3rd Period FAAA 4.12,72 11.12.72 70 16,983 7,250 101,898 PIMAAUA 5.12.72 8,12.72 151 27,766 .22,320 416,490 PAEA 5.12.72 14*12.72 86 18,051 8, 540 97,633 PAPARA 5.12.72 7.12.72 94 29,460 21,632 346,112 PAPARA 11.12.72 12. -

Innovations in Animal-Substrate Interactions Through Geologic Time

The other biodiversity record: Innovations in animal-substrate interactions through geologic time Luis A. Buatois, Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 114 Science Place, Saskatoon SK S7N 5E2, Canada, luis. [email protected]; and M. Gabriela Mángano, Dept. of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, 114 Science Place, Saskatoon SK S7N 5E2, Canada, [email protected] ABSTRACT 1979; Bambach, 1977; Sepkoski, 1978, 1979, and Droser, 2004; Mángano and Buatois, Tracking biodiversity changes based on 1984, 1997). However, this has been marked 2014; Buatois et al., 2016a), rather than on body fossils through geologic time became by controversies regarding the nature of the whole Phanerozoic. In this study we diversity trajectories and their potential one of the main objectives of paleontology tackle this issue based on a systematic and biases (e.g., Sepkoski et al., 1981; Alroy, in the 1980s. Trace fossils represent an alter- global compilation of trace-fossil data 2010; Crampton et al., 2003; Holland, 2010; native record to evaluate secular changes in in the stratigraphic record. We show that Bush and Bambach, 2015). In these studies, diversity. A quantitative ichnologic analysis, quantitative ichnologic analysis indicates diversity has been invariably assessed based based on a comprehensive and global data that the three main marine evolutionary on body fossils. set, has been undertaken in order to evaluate radiations inferred from body fossils, namely Trace fossils represent an alternative temporal trends in diversity of bioturbation the Cambrian Explosion, Great Ordovician record to assess secular changes in bio- and bioerosion structures. The results of this Biodiversification Event, and Mesozoic diversity. Trace-fossil data were given less study indicate that the three main marine Marine Revolution, are also expressed in the attention and were considered briefly in evolutionary radiations (Cambrian Explo- trace-fossil record. -

Boring Bivalve Traces in Modern Reef and Deeper-Water Macroid and Rhodolith Beds

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Previously Published Works Title Boring bivalve traces in modern reef and deeper-water macroid and rhodolith beds Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7rj146x4 Journal Progress in Earth and Planetary Science, 7(1) ISSN 2197-4284 Authors Bassi, D Braga, JC Owada, M et al. Publication Date 2020-12-01 DOI 10.1186/s40645-020-00356-w Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Bassi et al. Progress in Earth and Planetary Science (2020) 7:41 Progress in Earth and https://doi.org/10.1186/s40645-020-00356-w Planetary Science RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Boring bivalve traces in modern reef and deeper-water macroid and rhodolith beds Davide Bassi1* , Juan C. Braga2, Masato Owada3, Julio Aguirre2, Jere H. Lipps4, Hideko Takayanagi5 and Yasufumi Iryu5 Abstract Macroids and rhodoliths, made by encrusting acervulinid foraminifera and coralline algae, are widely recognized as bioengineers providing relatively stable microhabitats and increasing biodiversity for other species. Macroid and rhodolith beds occur in different depositional settings at various localities and bathymetries worldwide. Six case studies of macroid/rhodolith beds from 0 to 117 m water depth in the Pacific Ocean (northern Central Ryukyu Islands, French Polynesia), eastern Australia (Fraser Island, One Tree Reef, Lizard Island), and the Mediterranean Sea (southeastern Spain) show that nodules in the beds are perforated by small-sized boring bivalve traces (Gastrochanolites). On average, boring bivalve shells (gastrochaenids and mytilids) are more slender and smaller than those living inside shallow-water rocky substrates. In the Pacific, Gastrochaena cuneiformis, Gastrochaena sp., Leiosolenus malaccanus, L. -

Liste Des Labellisés CLCE Au 30 Novembre 2017 Arue Faaa

Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 TAHITI Arue ➢ DOMOTEC Contact : CHOUGUES Gilles 87 78 15 35 40 45 34 07 [email protected] Courrier : BP 14717 – 98701 ARUE Faaa 1 ➢ 987 ELEC Contact : WATANABE Otis 87 78 43 22 : 40 82 30 71 [email protected] Courrier : BP 61609 – 98702FAA’A ➢ ARESO Contact : MOUSSET Laurent 87 70 73 42 [email protected] Courrier : BP 61781 – 98704 FAA’A Centre ➢ ELEC 220 Contact : HERLEMME Mickael 87 74 73 09 [email protected] Courrier : BP 3341 – 98717 Punaauia Association Centre Label et Contrôle Electrique Téléphone : 40 47 27 72 Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 ➢ TEARATAI UIRA Contact : KONG YEK FHAN Christian 87 72 59 21 [email protected] Courrier : BP 6129 – 98704 FAA’A ➢ TECHNO FROID Contact : LANVIN Jérôme 40 80 04 05 40 80 04 09 [email protected] Courrier : BP 50354 – 98716 PIRAE Contact : TEHURITAUA Marc ➢ TEHURITAUA & FILS 2 87 77 36 21 [email protected] Courrier : BP 6276 – 98702 FAA’A Mahina ➢ A.E.S ELECTRICITE Contact : MICHON Nicolas 87 34 34 87 [email protected] Courrier : BP 90124 Motu Uta – 98715 Papeete ➢ POLY RESEAUX CONCEPT Contact : OPUTU John 87 34 63 24 [email protected] Association Centre Label et Contrôle Electrique Téléphone : 40 47 27 72 Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 Paea ➢ ELECTRICITE ET RESEAUX DE Contact : LALANDEC Patrick TAHITI (ERDT) 87 77 09 83 / 87 78 75 31 40 50 79 41 [email protected] Courrier : BP 50131 – 98716 PIRAE ➢ WES ELEC Contact : BUTSCHER Wesley 89 72 78 31 / 87 75 08 15 40 81 34 66 [email protected] / [email protected] -

Decoupled Evolution of Soft and Hard Substrate Communities During the Cambrian Explosion and Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event

Decoupled evolution of soft and hard substrate communities during the Cambrian Explosion and Great Ordovician Biodiversification Event Luis A. Buatoisa,1, Maria G. Mánganoa, Ricardo A. Oleab, and Mark A. Wilsonc aDepartment of Geological Sciences, University of Saskatchewan, Saskatoon, SK, Canada S7N 5E2; bEastern Energy Resources Science Center, US Geological Survey, Reston, VA 20192; and cDepartment of Geology, The College of Wooster, Wooster, OH 44691 Edited by Steven M. Holland, University of Georgia, Athens, GA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member David Jablonski May 6, 2016 (received for review November 21, 2015) Contrasts between the Cambrian Explosion (CE) and the Great shed light on the natures of both radiations. Because there is still Ordovician Biodiversification Event (GOBE) have long been recog- controversy regarding Sepkoski’s nonstandardized curves of nized. Whereas the vast majority of body plans were established Phanerozoic taxonomic diversity (13–15), a rarefaction analysis as a result of the CE, taxonomic increases during the GOBE were was performed in an attempt to standardize diversity data. The manifested at lower taxonomic levels. Assessing changes of ichno- aims of this paper are to document the contrasting ichnodiversity diversity and ichnodisparity as a result of these two evolutionary and ichnodisparity trajectories in soft and hard substrate com- events may shed light on the dynamics of both radiations. The early munities during these two evolutionary events and to discuss the Cambrian (series 1 and 2) displayed a dramatic increase in ichnodi- possible underlying causes of this decoupled evolution. versity and ichnodisparity in softground communities. In contrast to this evolutionary explosion in bioturbation structures, only a few Results Cambrian bioerosion structures are known. -

Marine Bioerosion 1 21.08.01

Marine Bioerosion 1 21.08.01 VL Marine Bioerosion VL 807.191 gelesen von / lecture given by dr. Karl Kleemann (Script zusammengestellt von / compiled by: P.Madl) Universität Wien Univerisity of Vienna Teil I Definitionen................................................................................ 2 Teil II Endolithische Bioerosion (ohne Bivalvia).................................. 6 Mikrobohrer (Bakteria, Fungi, Algae)........................................ 7 Porifera (Boring Sponges).......................................................... 9 Polychaeta (Annelids)................................................................. 11 Arthropoda (Crustaceans: Iso-, Decapods, Cirripeds)................ 11 Sipunculidae............................................................................... 12 Teil III Epilithische Bioerosion (incl. endolithish aktive Bivalvia)........ 13 Mollusca - (Käferschnecken und Bivalvia)................................ 14 Echinodermata (Urchins)............................................................ 18 Scaridae (Parrotfish)................................................................... 20 Pomacentridae (Damselfish)....................................................... 22 Teil IV Faktoren und Variationen der Bioerosion.................................. 23 Teil V Korallenkrankheiten................................................................... 24 Teil VI Literatur...................................................................................... 25 http://www.sbg.ac.at/ipk/avstudio/pierofun/funpage.htm -

Echinoid Community Structure and Rates of Herbivory and Bioerosion on Exposed and Sheltered Reefs

Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology 456 (2014) 8–17 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Experimental Marine Biology and Ecology journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jembe Echinoid community structure and rates of herbivory and bioerosion on exposed and sheltered reefs Omri Bronstein ⁎,YossiLoya Department of Zoology, The George S. Wise Faculty of Life Sciences, Tel-Aviv University, Tel-Aviv 69978, Israel article info abstract Article history: Echinoid–habitat relations are complex and bi-directional. Echinoid community structure is affected by the hab- Received 19 September 2013 itat structural and environmental conditions; while at the same time, echinoids may also act as ‘reef engineers’, Received in revised form 24 January 2014 able to alter marine environments on a wide geographic scale. In particular, echinoids play a major role in Accepted 9 March 2014 bioerosion and herbivory on coral reefs. Through feeding, echinoids reduce algal cover, enabling settlement Available online xxxx and coral growth. However, at the same time, they also remove large parts of the reef hard substrata, gradually Keywords: leading to reef degradation. Here, we compared coral and macroalgal abundance, echinoid community structure fi Bioerosion and species-speci c rates of echinoid herbivory and bioerosion on reefs subjected to different intensities of oce- Coral reefs anic exposure. Spatio-temporal variations in coral and macroalgal cover were monitored, and populations of the Herbivory four most abundant echinoid species on the coral reefs of Zanzibar – Diadema setosum (Leske), Diadema savignyi MPAs (Michelin), Echinometra mathaei (de Blainville) and Echinothrix diadema (Linnaeus) – were compared between Sea urchins the Island's eastern exposed reefs and western sheltered ones. -

Echinoderm Ichnology: Bioturbation, Bioerosion and Related Processes

Journal of Paleontology, 91(4), 2017, p. 643–661 Copyright © 2017, The Paleontological Society 0022-3360/17/0088-0906 doi: 10.1017/jpa.2016.146 Echinoderm ichnology: bioturbation, bioerosion and related processes Zain Belaústegui,1 Fernando Muñiz,2 James H. Nebelsick,3 Rosa Domènech,1 and Jordi Martinell1 1IRBio (Biodiversity Research Institute) and Departamento de Dinàmica de la Terra i de l’Oceà, Universitat de Barcelona (UB), Martí Franquès s/n, E-08028 Barcelona, Spain 〈[email protected]; [email protected]; [email protected]〉 2Departamento de Cristalografía, Mineralogía y Química Agrícola, Universidad de Sevilla (US), Avda. Reina Mercedes 6, E-41012 Sevilla, Spain 〈[email protected]〉 3Department of Geosciences, Hölderlinstrasse 12, 72074 Tübingen, Germany 〈[email protected]〉 Abstract.—Among invertebrates and both in modern and ancient marine environments, certain echinoderms have been and are some of the most active and widespread bioturbators and bioeroders. Bioturbation and/or bioerosion of regular and irregular echinoids, starfish, brittle stars, sea cucumbers and crinoids are known from modern settings, and some of the resulting traces have their counterparts in the fossil record. By contrast, surficial trails or trackways produced by other modern echinoderms, e.g., sand dollars, exhibit a lower preservation rate and have not yet been identified in the fossil record. In addition, the unique features of the echinoderm skeleton (e.g., composition, rapid growth, multi-element architecture, etc.) may promote the production of related traces produced by the reutilization of echinoderm ossicles (e.g., burrow lining), predation (e.g., borings), or parasitism (e.g., swellings or cysts). Finally, the skeletal robustness of some echinoids may promote their post mortum use as benthic islands for the settlement of hard-substrate dwellers. -

Effects of Ocean Acidification and Global Warming on Reef Bioerosion—Lessons from a Clionaid Sponge

Vol. 19: 111–127, 2013 AQUATIC BIOLOGY Published online September 24 doi: 10.3354/ab00527 Aquat Biol OPEN ACCESS Effects of ocean acidification and global warming on reef bioerosion—lessons from a clionaid sponge Max Wisshak1,*, Christine H. L. Schönberg2, Armin Form3, André Freiwald1 1Senckenberg am Meer, Marine Research Department, 26382 Wilhelmshaven, Germany 2Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS), University of Western Australia, Crawley, Western Australia 9006, Australia 3GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, Marine Biogeochemistry, 24105 Kiel, Germany ABSTRACT: Coral reefs are under threat, exerted by a number of interacting effects inherent to the present climate change, including ocean acidification and global warming. Bioerosion drives reef degradation by recycling carbonate skeletal material and is an important but understudied factor in this context. Twelve different combinations of pCO2 and temperature were applied to elu- cidate the consequences of ocean acidification and global warming on the physiological response and bioerosion rates of the zooxanthellate sponge Cliona orientalis—one of the most abundant and effective bioeroders on the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Our results confirm a significant amplifi- cation of the sponges’ bioerosion capacity with increasing pCO2, which is expressed by more car- bonate being chemically dissolved by etching. The health of the sponges and their photosymbionts was not affected by changes in pCO2, in contrast to temperature, which had significant negative impacts at higher levels. However, we could not conclusively explain the relationship between temperature and bioerosion rates, which were slightly reduced at both colder as well as warmer temperatures than ambient. The present findings on the effects of ocean acidification on chemical bioerosion, however, will have significant implications for predicting future reef carbonate budgets, as sponges often contribute the lion’s share of internal bioerosion on coral reefs.