The Pacific Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Répartition De La Population En Polynésie Française En 2017

Répartition de la population en Polynésie française en 2017 PIRAE ARUE Paopao Teavaro Hatiheu PAPEETE Papetoai A r c h MAHINA i p e l d FAA'A HITIAA O TE RA e s NUKU HIVA M a UA HUKA r q PUNAAUIA u HIVA OA i TAIARAPU-EST UA POU s Taiohae Taipivai e PAEA TA HUATA s NUKU HIVA Haapiti Afareaitu FATU HIVA Atuona PAPARA TEVA I UTA MOO REA TAIARAPU-OUEST A r c h i p e l d Puamau TAHITI e s T MANIHI u a HIVA OA Hipu RA NGIROA m Iripau TA KAROA PUKA P UKA o NA PUKA Hakahau Faaaha t u Tapuamu d e l a S o c i é MAKEMO FANGATA U - p e l t é h i BORA BORA G c a Haamene r MAUPITI Ruutia A TA HA A ARUTUA m HUAHINE FAKARAVA b TATAKOTO i Niua Vaitoare RAIATEA e TAHITI r TAHAA ANAA RE AO Hakamaii MOORE A - HIK UE RU Fare Maeva MAIAO UA POU Faie HA O NUKUTAVAKE Fitii Apataki Tefarerii Maroe TUREIA Haapu Parea RIMATARA RURUTU A r c h Arutua HUAHINE i p e TUBUAI l d e s GAMBIE R Faanui Anau RA IVAVAE A u s Kaukura t r Nombre a l AR UTUA d'individus e s Taahuaia Moerai Mataura Nunue 20 000 Mataiva RA PA BOR A B OR A 10 000 Avera Tikehau 7 000 Rangiroa Hauti 3 500 Mahu Makatea 1 000 RURUT U TUBUAI RANGIROA ´ 0 110 Km So u r c e : Re c en se m en t d e la p o p u la ti o n 2 0 1 7 - IS P F -I N SE E Répartition de la population aux Îles Du Vent en 2017 TAHITI MAHINA Paopao Papetoai ARUE PAPEETE PIRAE HITIAA O TE RA FAAA Teavaro Tiarei Mahaena Haapiti PUNAAUIA Afareaitu Hitiaa Papenoo MOOREA 0 2 Km Faaone PAEA Papeari TAIARAPU-EST Mataiea Afaahiti Pueu Toahotu Nombre PAPARA d'individus TEVA I UTA Tautira 20 000 Vairao 15 000 13 000 Teahupoo 10 000 TAIARAPU-OUEST -

Uncharted Seas: European-Polynesian Encounters in the Age of Discoveries

Uncharted Seas: European-Polynesian Encounters in the Age of Discoveries Antony Adler y the mid 18th century, Europeans had explored many of the world's oceans. Only the vast expanse of the Pacific, covering a third of the globe, remained largely uncharted. With the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, England and France once again devoted their efforts to territorial expansion and exploration. Government funded expeditions set off for the South Pacific, in misguided belief that the continents of the northern hemisphere were balanced by a large land mass in the southern hemisphere. Instead of finding the sought after southern continent, however, these expeditions came into contact with what 20th-century ethnologist Douglas Oliver has identified as a society "of surprising richness, complexity, vital- ity, and sophistication."! These encounters would lead Europeans and Polynesians to develop new interpretations of the "Other:' and change their understandings of themselves. Too often in the post-colonial world, historical accounts of first contacts have glossed them as simple matters of domination and subjugation of native peoples carried out in the course of European expansion. Yet, as the historian Charles H. Long writes in his critical overview of the commonly-used term transcu!turation: It is clear that since the fifteenth century, the entire globe has become the site of hundreds of contact zones. These zones were the loci of new forms of language and knowledge, new understandings of the nature of human rela- Published by Maney Publishing (c) The Soceity for the History of Discoveries tions, and the creation and production of new forms of human community. -

(A) No Person Or Corporation May Publish Or Reproduce in Any Manner., Without the Consent of the Committee on Research And-Graduate

RULES ADOPTED BY THE BOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII NOV 8 1955 WITH REGARD TO THE REPRODUCTION OF MASTERS THESES (a) No person or corporation may publish or reproduce in any manner., without the consent of the Committee on Research and-Graduate. Study, a. thesis which has been submitted to the University in partial fulfillment of the require ments for an advanced degree, {b ) No individual or corporation or other organization may publish quota tions or excerpts from a graduate thesis without the consent of the author and of the Committee on Research and Graduate Study. UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII LIBRARY A STUDY CF SOCIO-ECONOMIC VALUES OF SAMOAN INTERMEDIATE u SCHOOL STUDENTS IN HAWAII A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAII IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT CF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS JUNE 1956 Susan E. Hirsh Hawn. CB 5 H3 n o .345 co°“5 1 TABLE OP CONTENTS LIST GF TABUS ............................... iv CHAPTER. I. STATEMENT CP THE PROBLEM ........ 1 Introduction •••••••••••.•••••• 1 Th« Problem •••.••••••••••••••• 3 Methodology . »*••*«* i «#*•**• t * » 5 II. CONTEMPORARY SAMOA* THE CULTURE CP ORIGIN........ 10 Socio-Economic Structure 12 Soeic-Eoonosdo Chong« ••••••«.#•••«• 15 Socio-Economic Values? •••••••••••».. 17 Conclusions 18 U I . TBE SAIOAIS IN HAWAII» PEARL HARBOR AND LAXE . 20 Peerl Harbor 21 Lala ......... 24 Sumaary 28 IV. SELECTED BACKGROUND CHARACTERISTICS OP SAMOAN AND NON-SAMOAN INTERMEDIATE SCHOOL STUDENTS IN HAWAII . 29 Location of Residences of Students ••••••• -

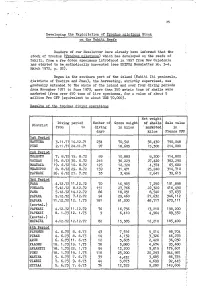

Developing the Exploitation of <I>Trochus Niloticus</I> Stock on the Tahiti Reefs

35 Developing the Exploitation of Trochu3 niloticus Stock onithe_Ta'hiti Reefs Readers of our Newsletter have already been informed that the stock of trochus (Trochug niloticus) which has developed on the reefs of Tahiti, from a few dozen specimens introduced in 1957 from Hew Caledonia has started to be methodically harvested (see SPIPDA Newsletter ITo. 3-4, March 1972, p. 32). Begun in the southern part of the island (Tahiti Iti peninsula, districts of Tautira and Pueu), the harvesting, strictly supervised, was gradually extended to the whole of the island and over four diving periods fjrom November 1971 to June 1973? more than 350 metric tons of shells were marketed (from over 450 tons of live specimens, for a value of about 5 million Frs CTP (equivalent to about US$ 70,000). Results of .the trochus. diving operations Net weight Diving period Number of Gross weight of shells Sale value District from to diving in kilos ' marketed in days kilos Francs CPP 1st Period TAUTIRA 3-11.71 I4.l2.7i 234 70,541 56,430 790,048 .. PUEU 2.11 .71 24.11.71 97 18,605 ... 15,300 214,000 2nd Period TOAHOTU 7. 8.72 15. 8,72 89 10r883 8,200 114,800 : VAIRAO 15. 8.72 30. 8.72 216 36J229 27,420 362,290 , MAATAIA. 19. 6.72 10. 8o72 125 12,724 4,374 65,600 TEAHUPOO 8. 8.72 29. 8.72 159 31,471 25,240' 314,710 PAPEARI 26. 6.72 27. 7.72 35 3,456 2,641 39,615 ; 3rd Period FAAA 4.12,72 11.12.72 70 16,983 7,250 101,898 PIMAAUA 5.12.72 8,12.72 151 27,766 .22,320 416,490 PAEA 5.12.72 14*12.72 86 18,051 8, 540 97,633 PAPARA 5.12.72 7.12.72 94 29,460 21,632 346,112 PAPARA 11.12.72 12. -

Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change

The I and the We: Individuality, Collectivity, and Samoan Artistic Responses to Cultural Change April K Henderson That the Samoan sense of self is relational, based on socio-spatial rela- tionships within larger collectives, is something of a truism—a statement of such obvious apparent truth that it is taken as a given. Tui Atua Tupua Tamasese Taisi Efi, a former prime minister and current head of state of independent Sāmoa as well as an influential intellectual and essayist, has explained this Samoan relational identity: “I am not an individual; I am an integral part of the cosmos. I share divinity with my ancestors, the land, the seas and the skies. I am not an individual, because I share a ‘tofi’ (an inheritance) with my family, my village and my nation. I belong to my family and my family belongs to me. I belong to my village and my village belongs to me. I belong to my nation and my nation belongs to me. This is the essence of my sense of belonging” (Tui Atua 2003, 51). Elaborations of this relational self are consistent across the different political and geographical entities that Samoans currently inhabit. Par- ticipants in an Aotearoa/New Zealand–based project gathering Samoan perspectives on mental health similarly described “the Samoan self . as having meaning only in relationship with other people, not as an individ- ual. This self could not be separated from the ‘va’ or relational space that occurs between an individual and parents, siblings, grandparents, aunts, uncles and other extended family and community members” (Tamasese and others 2005, 303). -

O Le Fogavaʻa E Tasi: Claiming Indigeneity Through Western Choral Practice in the Sāmoan Church

O Le Fogavaʻa e Tasi: Claiming Indigeneity through Western Choral practice in the Sāmoan Church Jace Saplan University of Hawai‘i, Mānoa Abstract Indigenous performance of Native Sāmoa has been constructed through colonized and decolonized systems since the arrival of western missionaries. Today, the western choral tradition is considered a cultural practice of Sāmoan Indigeniety that exists through intersections of Indigenous protocol and eurocentric performance practice. This paper will explore these intersections through an analysis of Native Sāmoan understandings of gender, Indigenous understandings and prioritizations of western vocal pedagogy, and the Indigenization of western choral culture. Introduction Communal singing plays a significant role in Sāmoan society. Much like in the greater sphere of Polynesia, contemporary Sāmoan communities are codified and bound together through song. In Sāmoa, sa (evening devotions), Sunday church services, and inter-village festivals add to the vibrant propagation of communal music making. These practices exemplify the Sāmoan values of aiga (family) and lotu (church). Thus, the communal nature of these activities contributes to the cultural value of community (Anae, 1998). European missionaries introduced hymn singing and Christian theology in the 1800s; this is acknowledged as a significant influence on the paralleled values of Indigenous thought, as both facets illustrate the importance of community (McLean, 1986). Today, the church continues to amplify the cultural importance of community, and singing remains an important activity to propagate these values. In Sāmoa, singing is a universal activity. The vast majority of Native Sāmoans grow up singing in the church choir, and many Indigenous schools require students to participate in the school choir. -

Origins of Sweet Potato and Bottle Gourd in Polynesia: Pre-European Contacts with South America?

Seminar Origins of sweet potato and bottle gourd in Polynesia: pre-European contacts with South America? Dr. Andrew Clarke Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution, Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland, New Zealand Wednesday, April 15th – 3:00 pm. Phureja Room This presentation will be delivered in English, but the slides will be in Spanish. Abstract: It has been suggested that both the sweetpotato (camote) and bottle gourd (calabaza) were introduced into the Pacific by Polynesian voyagers who sailed to South America around AD 1100, collected both species, and returned to Eastern Polynesia. For the sweetpotato, this hypothesis is well supported by archaeological, linguistic and biological evidence, but using molecular genetic techniques we are able to address more specific questions: Where in South America did Polynesians make landfall? What were the dispersal routes of the sweetpotato within Polynesia? What was the influence of the Spanish and Portuguese sweetpotato introductions to the western Pacific in the 16th century? By analysing over 300 varieties of sweet potato from the Yen Sweet Potato Collection in Tsukuba, Japan using high-resolution DNA fingerprinting techniques we are beginning to elucidate specific patterns of sweetpotato dispersal. This presentation will also include discussion of the Polynesian bottle gourd, and our efforts to determine whether it is of South American or Asian origin. Understanding dispersal patterns of both the sweetpotato and bottle gourd is adding to our knowledge of human movement in the Pacific. It also shows how germplasm collections such as those maintained by the International Potato Center can be used to answer important anthropological questions. -

Introduction Navigating Spatial Relationships in Oceania

INTRODUCTION NAVIGATING SPATIAL RELATIONSHIPS IN OCEANIA Richard Feinberg Department of Anthropology Kent State University Kent OH USA [email protected] Cathleen Conboy Pyrek Independent Scholar Rineyville, KY [email protected] Alex Mawyer Center for Pacific Island Studies University of Hawai’i at Mānoa Honolulu, HI USA [email protected] Recent decades have seen a revival of interest in traditional voyaging equipment and techniques among Pacific Islanders. At key points, the Oceanic voyaging revival came together with anthropological interests in cognition. This special issue explores that intersection as it is expressed in cognitive models of space, both at sea and on land. These include techniques for “wave piloting” in the Marshall Islands, wind compasses and their utilization as part of an inclusive navigational tool kit in the Vaeakau-Taumako region of the Solomon Islands; notions of ‘front’ and ‘back’ on Taumako and in Samoa, ideas of ‘above’ and ‘below’ in the Bougainville region of Papua New Guinea, spaces associated with the living and the dead in the Trobriand Islands, and the understanding of navi- gation in terms of neuroscience and physics. Keywords: cognition, navigation, Oceania "1 Recent decades have seen a revival of interest in traditional voyaging equipment and techniques among Pacific Islanders. That resurgence was inspired largely by the exploits of the Polynesian Voyaging Society and its series of successful expeditions, beginning with the 1976 journey of Hōkūle‘a, a performance-accurate replica of an early Hawaiian voyaging canoe, from Hawai‘i to Tahiti (Finney 1979, 1994; Kyselka 1987). Hōkūle‘a (which translates as ‘Glad Star’, the Hawaiian name for Arcturus) has, over the ensuing decades, sailed throughout the Polynesian Triangle and beyond. -

Bioerosion of Experimental Substrates on High Islands and on Atoll Lagoons (French Polynesia) After Two Years of Exposure

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 166: 119-130,1998 Published May 28 Mar Ecol Prog Ser -- l Bioerosion of experimental substrates on high islands and on atoll lagoons (French Polynesia) after two years of exposure 'Centre d'oceanologie de Marseille, UMR CNRS 6540, Universite de la Mediterranee, Station Marine d'Endoume, rue de la Batterie des Lions, F-13007 Marseille, France 2Centre de Sedimentologie et Paleontologie. UPRESA CNRS 6019. Universite de Provence, Aix-Marseille I, case 67, F-13331 Marseille cedex 03. France 3The Australian Museum, 6-8 College Street, 2000 Sydney, New South Wales, Australia "epartment of Biology, Boston University, Boston, Massachusetts 02215, USA ABSTRACT: Rates of bioerosion by grazing and boring were studied in lagoons of 2 high islands (3 sites) and 2 atolls (2 sites each) In French Polynesia using experimental carbonate substrates (blocks of Porites lutea skeleton). The substrate loss versus accretion was measured after 6 and 24 mo of exposure. The results show significant differences between pristine environments on atolls and envi- ronments on high islands sub!ected to different levels of eutrophication and pollution due to human activities. Whereas experimental substrates on the atolls maintain a balance between accretion and erosion or exhibit net gains from accretion (positive budget), only 1 site on a high island exhibits sig- nificant loss of substrate by net erosion (negative budget). The erosional patterns set within the first 6 rno of exposure were largely maintained throughout the entire duration of the expeiiment. The inten- sity of bioerosion by grazing increases dramatically when reefs are exposed to pollution from harbour waters; this is shown at one of the Tahiti sites, where the highest average bioerosional loss, up to 25 kg m-2 yr-' (6.9 kg m-' yr-I on a single isolated block), of carbonate substrate was recorded. -

Melanesia and Polynesia

Community Conserved Areas: A review of status & needs in Melanesia and Polynesia Hugh Govan With Alifereti Tawake, Kesaia Tabunakawai, Aaron Jenkins, Antoine Lasgorceix, Erika Techera, Hugo Tafea, Jeff Kinch, Jess Feehely, Pulea Ifopo, Roy Hills, Semese Alefaio, Semisi Meo, Shauna Troniak, Siola’a Malimali, Sylvia George, Talavou Tauaefa, Tevi Obed. February 2009 Acknowledgments Gratitude for interviews and correspondence is due to: Aliti Vunisea, Ana Tiraa, Allan Bero, Anne-Maree Schwarz, Bill Aalbersberg, Bruno Manele, Caroline Vieux, Delvene Notere, Daniel Afzal, Barry Lally, Bob Gillett, Brendon Pasisi, Christopher Bartlett, Christophe Chevillon, Christopher Bartlett, Dave Fisk, David Malick, Eroni Tulala Rasalato, Helen Sykes, Hugh Walton, Etika Rupeni, Francis Mamou, Franck Magron, Grazia Borrini-Feyerabend, Helen Perks, Hugh Walton, Isoa Korovulavula, James Comley, Jackie Thomas, Jacqueline Evans, Jane Mogina, Jo Axford, Johann Bell, John Parks, John Pita, Jointly Sisiolo, Julie Petit, Louise Heaps, Paul Anderson, Pip Cohen, Kiribati Taniera, Kori Raumea, Luanne Losi, Lucy Fish, Ludwig Kumoru, Magali Verducci, Malama Momoemausu, Manuai Matawai, Meghan Gombos, Modi Pontio, Mona Matepi, Olofa Tuaopepe, Pam Seeto, Paul Lokani, Peter Ramohia, Polangu Kusunan, Potuku Chantong, Rebecca Samuel, Ron Vave, Richard Hamilton, Seini Tawakelevu, Selaina Vaitautolu, Selarn Kaluwin, Shankar Aswani, Silverio Wale, Simon Foale, Simon Tiller, Stuart Chape, Sue Taei, Susan Ewen, Suzie Kukuian, Tamlong Tabb, Tanya O’Garra, Victor Bonito, Web Kanawi, -

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project

Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project Gary T. Kubota Hawaii Stories of Change Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project by Gary T. Kubota Copyright © 2018, Stories of Change – Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project The Kokua Hawaii Oral History interviews are the property of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project, and are published with the permission of the interviewees for scholarly and educational purposes as determined by Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. This material shall not be used for commercial purposes without the express written consent of the Kokua Hawaii Oral History Project. With brief quotations and proper attribution, and other uses as permitted under U.S. copyright law are allowed. Otherwise, all rights are reserved. For permission to reproduce any content, please contact Gary T. Kubota at [email protected] or Lawrence Kamakawiwoole at [email protected]. Cover photo: The cover photograph was taken by Ed Greevy at the Hawaii State Capitol in 1971. ISBN 978-0-9799467-2-1 Table of Contents Foreword by Larry Kamakawiwoole ................................... 3 George Cooper. 5 Gov. John Waihee. 9 Edwina Moanikeala Akaka ......................................... 18 Raymond Catania ................................................ 29 Lori Treschuk. 46 Mary Whang Choy ............................................... 52 Clyde Maurice Kalani Ohelo ........................................ 67 Wallace Fukunaga .............................................. -

Liste Des Labellisés CLCE Au 30 Novembre 2017 Arue Faaa

Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 TAHITI Arue ➢ DOMOTEC Contact : CHOUGUES Gilles 87 78 15 35 40 45 34 07 [email protected] Courrier : BP 14717 – 98701 ARUE Faaa 1 ➢ 987 ELEC Contact : WATANABE Otis 87 78 43 22 : 40 82 30 71 [email protected] Courrier : BP 61609 – 98702FAA’A ➢ ARESO Contact : MOUSSET Laurent 87 70 73 42 [email protected] Courrier : BP 61781 – 98704 FAA’A Centre ➢ ELEC 220 Contact : HERLEMME Mickael 87 74 73 09 [email protected] Courrier : BP 3341 – 98717 Punaauia Association Centre Label et Contrôle Electrique Téléphone : 40 47 27 72 Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 ➢ TEARATAI UIRA Contact : KONG YEK FHAN Christian 87 72 59 21 [email protected] Courrier : BP 6129 – 98704 FAA’A ➢ TECHNO FROID Contact : LANVIN Jérôme 40 80 04 05 40 80 04 09 [email protected] Courrier : BP 50354 – 98716 PIRAE Contact : TEHURITAUA Marc ➢ TEHURITAUA & FILS 2 87 77 36 21 [email protected] Courrier : BP 6276 – 98702 FAA’A Mahina ➢ A.E.S ELECTRICITE Contact : MICHON Nicolas 87 34 34 87 [email protected] Courrier : BP 90124 Motu Uta – 98715 Papeete ➢ POLY RESEAUX CONCEPT Contact : OPUTU John 87 34 63 24 [email protected] Association Centre Label et Contrôle Electrique Téléphone : 40 47 27 72 Liste des Labellisés CLCE au 30 novembre 2017 Paea ➢ ELECTRICITE ET RESEAUX DE Contact : LALANDEC Patrick TAHITI (ERDT) 87 77 09 83 / 87 78 75 31 40 50 79 41 [email protected] Courrier : BP 50131 – 98716 PIRAE ➢ WES ELEC Contact : BUTSCHER Wesley 89 72 78 31 / 87 75 08 15 40 81 34 66 [email protected] / [email protected]