Full Text in Pdf Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lake Huron Spawning

Thunder Bay River Assessment Appendix Pink salmon (Oncorhynchus gorbuscha) Habitat: feeding - large cold deep lakes - Lake Huron spawning - gravel substrate in rivers - female prepares and guards nest until death 0 5 10 Miles Alpena Hillman Atlanta Thunder Bay Lake Huron 98 Thunder Bay River Assessment Appendix Coho salmon (Oncorhynchus kisutch) Habitat: feeding - adults: Lake Huron - young: shallow gravel substrate in cold streams, later into pools spawning - cold streams and rivers - swifter water of shallow gravelly substrate 0 5 10 Miles Alpena Hillman Atlanta Thunder Bay Lake Huron 99 Thunder Bay River Assessment Appendix Rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) Habitat: feeding - cold clear water of rivers and Lake Huron - moderate current spawning - gravelly riffles above a pool - smaller tributaries 0 5 10 Miles Alpena Hillman Atlanta Thunder Bay Lake Huron 100 Thunder Bay River Assessment Appendix Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawyscha) Habitat: feeding - adults: Lake Huron - young: shallow gravel substrate in cool streams, later into pools spawning - gravelly substrate in cool streams 0 5 10 Miles Alpena Hillman Atlanta Thunder Bay Lake Huron 101 Thunder Bay River Assessment Appendix Round whitefish (Prosopium cylindraceum) Habitat: feeding - lakes, rivers, and streams spawning - shallows of lakes and rivers - gravel or rock substrate 0 5 10 Miles Alpena Hillman Atlanta Thunder Bay Lake Huron 102 Thunder Bay River Assessment Appendix Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) Habitat: feeding - young: gravel substrate streams - adults: Lake Huron -

Salmon Fact Sheet

THE WILD SALMON SEAFOOD MARKET’S GUIDE TO W I L D P A C I F I C S A L M O N Salmon Pacific Salmon occur from northern California along the Pacific Coast throughout the Pacific Ocean, Bering Sea and Arctic Ocean waters adjacent to Alaska. Salmon are anadromous, that is, they spawn in fresh water and the young migrate to the sea where they mature. The mature Salmon returns to the stream of their birth to spawn. Nutrition Few single foods bring as many valuable contributions to the table as Salmon. An excellent source of high-quality protein, containing all the essential amino acids. The fats in Salmon are predominately unsaturated. These fats are evidenced to reduce the risk of heart disease. Availability Although each species has a particular season, small fisheries of wild salmon occur periodically, making fresh salmon (often hard to find and expensive) available throughout the year. Your best values will come during peak salmon season, May through September. Frozen salmon (often frozen at sea) is available during the off season. Also known as Chinook Salmon. Also known as Silver Salmon. Highly desired for King The largest of the species and the most Coho both table use and smoking. Coho salmon offers prominent of the salmon known for its high oil firm meat with excellent flavor slightly milder than content and distinctive, rich flavor. King and Sockeye. Average size from 5 to 40 lbs. Average size from 4 - 9 lbs. Available May - September Available June - September Copper River & Yukon River King Also known as Chum Salmon. -

Imagine the Silver Beauty and the Fighting Spirit of Atlantic Salmon; The

Sakhalin Silver Text and Photos: Clemens Ratschan Imagine the silver beauty and the fighting spirit of Atlantic salmon; the complex, unpredictable life- history of sea trout and combine with the ferocious take and body mass of a predatory taimen. This will give you a glimpse of what fishing for Sakhalin taimen, the silver of the Russian Far East, is about. AM PLEASED TO introduce Siberian taimen, Hucho taimen. No this fish to the readers of wonder, scientists also erroneously Chasing Silver, because in related this far-eastern species to many respects it forms a the large-sized, non-anadromous missing link between the predators of the genus Hucho, which Ifishery for anadromous salmon and is a branch of the salmonoid tree for huchen, a big predatory non- that occurs exclusively in Eurasia. anadromous salmonoid in my home In Central Europe, Hucho hucho is country of Austria (‘Danube salmon’ restricted to the Danube System, in English. See article “Taimen” by where self-sustaining stocks are Wolfgang Hauer, issue 3/2010). presently only found in a handful of Sakhalin taimen is one of the rivers in Germany, Austria, Slovakia least-known salmonid species among and former Yugoslavia. Huchen is non-Russian fishermen; even many very closely related to the already- Russians tend to confuse it with the mentioned Siberian taimen. The latter | 62 | Chasing Silver Fly Fishing Magazine April’s Fav Five www.chasingsilvermagazine.com | 63 | Sakhalin Silver inhabits a distant, vast range from a habits. But one ecological feature expeditions to Japan. Later, the fish few places in European Russia to the is unique – all members of the true was assigned to the genus Parahucho, Lena and Amur rivers in the very far huchen live exclusively in fresh water, with regard to some obvious east of northern Asia. -

Variation in Salmonid Life Histories: Patterns and Perspectives

United States Department of Agriculture Variation in Salmonid Life Forest Service Histories: Patterns and Pacific Northwest Research Station Perspectives Research Paper PNW-RP-498 Mary F. Willson February 1997 Author MARY F. WILLSON is a research ecologist, Forestry Sciences Laboratory, 2770 Sherwood Lane, Juneau, AK 98801. Abstract Willson, Mary F. 1997. Variation in salmonid life histories: patterns and perspectives. Res. Pap. PNW-RP-498. Portland, OR: U.S. Department of Agriculture, Forest Service, Pacific Northwest Research Station. 50 p. Salmonid fishes differ in degree of anadromy, age of maturation, frequency of repro- duction, body size and fecundity, sexual dimorphism, breeding season, morphology, and, to a lesser degree, parental care. Patterns of variation and their possible signif- icance for ecology and evolution and for resource management are the focus of this review. Keywords: Salmon, char, Oncorhynchus, Salmo, Salvelinus, life history, sexual dimor- phism, age of maturation, semelparity, anadromy, phenology, phenotypic variation, parental care, speciation. Summary Salmonid fishes differ in degree of anadromy, age of maturation, frequency of reproduction, body size and fecundity, sexual dimorphism, breeding season, morphology, and to a lesser degree, parental care. The advantages of large body size in reproductive competition probably favored the evolution of ocean foraging, and the advantages of safe breeding sites probably favored freshwater spawning. Both long-distance migrations and reproductive competition may have favored the evolution of semelparity. Reproductive competition has favored the evolution of secondary sexual characters, alternative mating tactics, and probably nest-defense behavior. Salmonids provide good examples of character divergence in response to ecological release and of parallel evolution. The great phenotypic plasticity of these fishes may facilitate speciation. -

Attention California Ocean Salmon Anglers

Attention California Ocean Salmon Anglers Please check your catch! Coho salmon are frequently contacted in California’s ocean fisheries. Although some of these salmon may have originated from Oregon or Washington, many are California coastal coho salmon, which are protected under the Endangered Species Act. Thus the retention of coho salmon is PROHIBITED in all California ocean fisheries. Please take the time to correctly identify each salmon caught before removing it from the water. All coho must be released. *Photo by CDFW Warden Bob Aldrich Help avoid contacting coho salmon: Rig to fish deeper - coho are more often in the top 30 feet of water. Fish nearshore for Chinook - coho are usually more offshore. Use large lures that select for larger Chinook and reduce coho catch. For additional information, please check the CDFW website at www.dfg.ca.gov/marine/oceansalmon.asp or call the Ocean Salmon Hotline at (707) 576-3429 Note: A few pink salmon have been caught in past seasons, usually in odd numbered years. Pink salmon are generally smaller than Chinook and coho salmon and can be identified by the large, oval- shaped spots found on their back and on both lobes of the tail fin. Their scales are very small and number over 168 in the row above the lateral line. The minimum size limit in California for pink salmon is the same as Chinook. The daily bag/possession limit remains 2 salmon of any species except coho. . -

HOW to IDENTIFY the FIVE SALMON SPECIES Found in the KODIAK ISLAND/ALASKA PENINSULA AREA

HOW TO IDENTIFY the FIVE SALMON SPECIES found in the KODIAK ISLAND/ALASKA PENINSULA AREA KING (CHINOOK) SALMON: COHO (SILVER) SALMON: Greenish-blue Blue-gray back with silvery sides. Small, irregular- back with silvery sides. Small black spots on the back, shaped black spots on back, dorsal fi n, and usually on dorsal fi n, and both lobes of the tail. usually on Black mouth with white upper lobe gums at base of teeth on of tail lower jaw. only. Spawning coho salmon adults develop Black mouth with black gums greenish-black heads and dark brown to at base of teeth on lower jaw. maroon bodies. Salmon mouth illustrations courtesy of California Department Fish and Game SOCKEYE (RED) SALMON: Dark blue-black back with silvery sides. No distinct Spawning spots on back, king salmon dorsal fi n, adults lose their or tail. silvery bright color and take Spawning sockeye salmon adults develop dull on a maroon to olive brown color. green colored heads and brick-red to scarlet bodies. CHUM (DOG) SALMON: Dull gray back PINK SALMON (HUMPIES): with yellowish-silver sides. Very large spots on the back No distinct spots on back and large black oval blotches or tail. Large eye pupil— on both tail lobes. Very small covers nearly the entire eye. scales. Spawning adults take on a dull gray coloration on the back and Spawning adults develop olive green upper sides with a creamy white coloration on the back with maroon color below. Males develop a sides covered with irregular dull red pronounced hump. bars. Males exhibit many large canine- like teeth. -

Pink Salmon Chances for Survival: Very Poor 1 Oncorhynchus Gorbuscha

Pink Salmon chances for survival: very poor 1 Oncorhynchus gorbuscha ink salmon are the smallest of the pacific salmon, with adults usually 18 disTriBuTion: spawning pink salmon ascend coastal StaTus 1: pink salmon are considered extirpated from 1 2 3 4 5 SALMON streams of northern asia, from Korea and Japan, and along California, except for occasional strays. however, recent to 25 inches in length. spawning males have a pronounced hump (and the coast of North america south to California. in California, reports of a spawning run in the Garcia river suggest that are often called humpback salmon) with a snout that is greatly enlarged there are records from many coastal streams but spawning a small population may have been overlooked. it is highly in recent years has only been recorded in the Garcia, russian, likely that pink salmon will disappear completely from p Pink Salmon Distribution and hooked. the body color is dark purplish, especially on the head and back. and sacramento rivers, as well as redwood Creek. California streams in the future, although it is possible aBundanCe: pink salmon are extremely abundant in that these populations periodically go extinct and then spawning females resemble trout in general body shape and are paler in color. alaska and Canada and support major commercial fisheries re-establish when pink salmon are abundant elsewhere. ConservaTion reCommendaTions: Nothing is known about the genetic background of California pink salmon, but there. California is the southern edge of the species’ range so the first step they have never been common here. however, given that pink in conservation of pink salmon is to determine if there populations in Washington have spawning runs in odd years and are regarded as salmon spawn in the lower reaches of streams in autumn are any reproducing populations in California. -

Sockeye Salmon

Sockeye Salmon The sockeye salmon (Oncorhynchus nerka), often referred to as "red" or "blueback" salmon, occurs in the North Pacific and Arctic oceans and associated freshwater systems. This species ranges south as far as the Klamath River in California and northern Hokkaido in Japan, to as far north as far as Bathurst Inlet in the Canadian Arctic and the Anadyr River in Siberia. Aboriginal people considered sockeye salmon to be an important food source and either ate them fresh or dried them for winter use. Today sockeye salmon support one of the most important commercial fisheries on the Pacific coast of North America, are increasingly sought after in recreational fisheries, and remain an important mainstay of many subsistence users. General description: Sockeye salmon can be distinguished from Chinook, coho, and pink salmon by the lack of large, black spots and from chum salmon by the number and shape of gill rakers on the first gill arch. Sockeye salmon have 28 to 40 long, slender, rough or serrated closely set rakers on the first arch. Chum salmon have 19 to 26 short, stout, smooth rakers. Immature and prespawning sockeye salmon are elongate, fusiform, and somewhat laterally compressed. They are metallic green blue on the back and top of the head, iridescent silver on the sides, and white or silvery on the belly. Some fine black speckling may occur on the back, but large spots are absent. Juveniles, while in fresh water, have the same general coloration as immature sockeye salmon in the ocean, but are less iridescent. Juveniles also have dark, oval parr marks on their sides. -

Green River Juvenile Salmonid Production Evaluation: 2009-2010 Annual Report

STATE OF WASHINGTON January 2011 Green River Juvenile Salmonid Production Evaluation: 2009-2010 Annual Report by Pete Topping, and Mara Zimmerman Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Fish Program Science Division FPA 11-01 Green River Juvenile Salmonid Production Evaluation: 2009 and 2010 Annual Report Pete Topping Mara Zimmerman Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife Fish Program, Science Division January 2011 Acknowledgements Measuring juvenile salmon production from large river systems like the Green River involves a tremendous amount of work. Developing these estimates was possible due to the long hours of trap operation provided by our dedicated scientific technicians: Bob Green, Josh Weinheimer, Matt Pollack, Jeff Loveland and Paul Lorenz. Logistical support was provided by Wild Salmon Production Evaluation Unit biologist Mike Ackley. A number of other individuals and agencies contributed to this project. Bill Mosby, the adjacent landowner, provided access to the trap site. Mike Wilson, manager of the WDFW Soos Creek hatchery, provided logistical support and a secure staging site near the trap. Steve Foley and Darcy Wildermuth, WDFW Region 4, provided Chinook spawner survey data. The juvenile salmonid production study on the Green River was initiated in 2000. This study was funded by the Washington State legislature between 2000 and 2002, by the Washington Salmon Recovery Funding Board (SRFB) between 2002 and 2007, and by Tacoma Public Utilities, Water Division between 2008 and 2010. Green River Juvenile Salmonid Production -

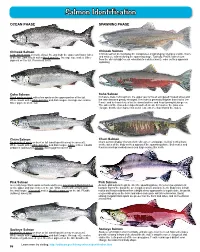

Salmon Identification

Salmon Identification OCEAN PHASE SPAWNING PHASE Chinook Salmon Chinook Salmon Large black spots on back, dorsal fin, and both the upper and lower lobes Chinook salmon do not display the conspicuous morphological changes of pink, chum, of the tail. Dark mouth with a black gum line. Average size scales. Silver and sockeye salmon during the spawning stage. Typically, Pacific salmon turn pigment on the tail. Prominent teeth. from the silvery bright ocean coloration to a darker bronze color as they approach spawning. Coho Salmon Coho Salmon Black spots on back with a few spots on the upper portion of the tail. In mature male coho salmon, the upper jaw forms an elongated hooked snout and White mouth with a white gum line and dark tongue. Average size scales. the teeth become greatly enlarged. The male is generally brighter than that of the Silver pigment on the tail. female and is characterized by the dorsal surface and head turning bluish-green. The sides of the males develop a broad red streak. In females, the jaws also elongate but the development is much less extreme than that of the males. Chum Salmon Chum Salmon No prominent spots on back or tail (small speckles may be present). Chum salmon display characteristic olive-green and purple (calico) vertical bars White mouth with a white gum line and dark tongue. Large scales. Caudal on the sides of the body as they approach the spawning phase. Both males and peduncle (tail base) is slender. Silver pigment on the tail. females develop hooked noses and large canine-like teeth Pink Salmon Pink Salmon Generally large black spots on back and heavy oval shaped black blotches As male pink salmon begin to enter the spawning phase, they develop a prominent on the upper and lower lobes of the tail. -

I {Ik'$- Tt Do 'R"--- F:F';; I!, F a // Rlws "I,;L"; Ltr/ Trp'',.R.,1$\\ , A,/ Lt F-2{- L6pzo- Zo 70

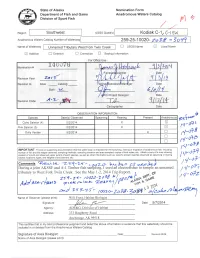

State of Alaska Nomination Form Department of Fish and Game Anadromous Waters Gatalog Division of Sport Fish rfiq Region Southwest USGS Quad(s) Anadromous Waters Catalog Number of Wut"*"V g Name of Waterway Unnamed Tributary West Fork Twin Creek n USGS Name Local Name E Addition I Deletion fl Correction n Backup Information For Office Use OBSERVATION I N FORMATION Fe-$n"* (!-O?t Pink Salmon (5) fl-&6 N-,Y+O IMPORTANT: Provide all supporting documentation that this water body is important for the spawning, rearing or migration of anadromous fish, including: lq-o7:, number of fish and life stages observed; sampling methods, sampling duration and area sampled; copies of field notes; elc. Attach a copy of a map showing location of mouth and observed upper elitent of each species, as well as other information such as: specific stream reaches observed as spawning or rearing /v4+7 habitat; locations, types, and heights of any barriers; etc. tRei,t{.- / !'ol' Comments a-S:1-at- r;o7p h.,r)e. OS tqlb) During a joint AKSSF and A-1 Timber fish sdrfr"pling, I used afi electrofisher to sample an unnamed / ./-o+; tributary to West Fork Twin Creek. See the May 1-2,20l4Trip Report. r - at / g- o7z i {ik'$- tt do 'r"--- f:f';; i!, f A // rlws "i,;L"; ltr/ trp'',.r.,1$\\ , a,/ Lt f-2{- l6pzo- zo 70. gd#1 u'}ifi., Trlt Name of Observer (please print): Habitat Bi Signature: Date: 51712014 Agency: ADF&G, Division of Habitat Address: 333 Raspberry Road Anchorage, AK 99518 This certifies that in my best professional judgment and belief the above information is evidence that this waterbody should be included in or deleted from the Anadromous Waters Catalog. -

Migratory Behaviors in Masu Salmon (Oncorhynchus Masou) and the Influence of Endocrinological Factors

Aqua-BioScience Monographs, Vol. 5, No. 2, pp. 29–65 (2012) www.terrapub.co.jp/onlinemonographs/absm/ Migratory Behaviors in Masu Salmon (Oncorhynchus masou) and the Influence of Endocrinological Factors Arimune Munakata Department of Biology Miyagi University of Education Aoba-ku, Sendai, Miyagi 980-0845, Japan e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Received on April 1, 2011 In the freshwater phase of their lifecycle, masu salmon (Oncorhynchus masou) comprise Accepted on September 22, 2011 two different phenotypes. A portion of the juveniles (migratory form) exhibit downstream Online published on November 20, 2012 migratory behavior after smoltification. However, some masu salmon (non-migratory form) such as precociously mature males live continuously in their natal rivers throughout their Keywords lifetime. The coexistence of migratory and non-migratory forms within the species indi- • cortisol cates that this salmon can be effectively used as a model fish to illuminate both inhibitory • downstream migration and stimulatory physiological control mechanisms of migratory behaviors. In masu salmon, • masu salmon it was found that sex steroid hormones inhibit the occurrence of downstream swimming • Oncorhynchus masou behavior, the initial step in seaward migration. Moreover, after the commencement of • Pacific salmon • sex steroid hormone downstream migration, sex steroid hormones induced the upstream swimming and subse- • spawning quent spawning behaviors. These findings indicate that sex steroid hormones influence • testosterone the occurrence of the downstream and upstream swimming behavior in the resulting rheo- • upstream migration taxis fashion (negative and positive, respectively). In contrast to sex steroid hormones, it was also found that cortisol, which is involved substantially in smoltification, stimulates the downstream swimming behavior.