Personal Distributed Computing: the Alto and Ethernet Software

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word Microsoft Office Word 2007 in Windows Vista Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.0.6425.1000 (2007 SP2) / April 28, 2009 Operating system Microsoft Windows Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [1] Website Microsoft Word Windows Microsoft Word 2008 in Mac OS X 10.5. Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.2.1 Build 090605 (2008) / August 6, 2009 Operating system Mac OS X Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [2] Website Microsoft Word Mac Microsoft Word is Microsoft's word processing software. It was first released in 1983 under the name Multi-Tool Word for Xenix systems.[3] [4] [5] Versions were later written for several other platforms including IBM PCs running DOS (1983), the Apple Macintosh (1984), SCO UNIX, OS/2 and Microsoft Windows (1989). It is a component of the Microsoft Office system; however, it is also sold as a standalone product and included in Microsoft Microsoft Word 2 Works Suite. Beginning with the 2003 version, the branding was revised to emphasize Word's identity as a component within the Office suite; Microsoft began calling it Microsoft Office Word instead of merely Microsoft Word. The latest releases are Word 2007 for Windows and Word 2008 for Mac OS X, while Word 2007 can also be run emulated on Linux[6] . There are commercially available add-ins that expand the functionality of Microsoft Word. History Word 1981 to 1989 Concepts and ideas of Word were brought from Bravo, the original GUI writing word processor developed at Xerox PARC.[7] [8] On February 1, 1983, development on what was originally named Multi-Tool Word began. -

SDS 940 THEORY of OPERATION Technical Manual SDS 98 01 26A

SDS 940 THEORY OF OPERATION Technical Manual SDS 98 01 26A March 1967 SCIENTIFIC DATA SYSTEMS/1649 Seventeenth Street/Santa Monica, California/UP 1-0960 ® 1967 Scientific Data Systems, Inc. Printed in U. S. A. TABLE OF CONTENTS Section Page I GENERAL DESCRIPTION ...•.••.•••••.••.••.•..•.••••• 1-1 1.1 General ................................... 1-1 1.2 Documentation .•...•..•.••..•••••••.•.••.••••• 1-1 1 .3 Physical Description ..•...•.••••.••..••••..••••. 1-2 1.4 Featu re s • . • . • • • • . • • • • • . • • . • . • . • • . • • • 1-2 1 .5 Input/Output Capabi I ity •.•....•.•.......•.....•.. 1-2 1 .5. 1 Parallel Input/Output System .•...•.....••..•. 1-6 1.5.1.1 Word Parallel System ...........•.. 1-6 1.5.1.2 Single-Bit Control and Sense System .... 1-8 1 .5.2 Time-Multiplexed Communication Channels .....•. 1-8 1 .5.3 Direct Memory Access System ............... 1-9 1.5.3.1 Direct Access Communication Channels •. 1-9 1.5.3.2 Data Multiplexing System ...•.....•. 1-10 1 .5.4 Priority Interrupt System . • . 1-10 1.5.4.1 Externa I Interrupt •..........•.... 1-11 1.5.4.2 Input/Output Channe I ..•..•.•••••. 1-12 1.5.4.3 Real-Time Clock •••.••.••••••••• 1-12 1 .6 Input/Output Devices •..•..••.••.••.••.•••••..•. 1-12 1 .6. 1 Buffered Input/Output Devices ..••.••.•.•••.•• 1-12 1.6.2 Unbuffered Input/Output Devices ••••..••••..•• 1-14 II OPERATION AND PROGRAMMING •..•••••.••.•..•....••. 2-1 2. 1 General .•..•.......•......•..............•. 2-1 2.2 Chang i ng Operat ion Modes •.•.••.••.•••.•..•..•.•• 2-2 2.3 Modes of Operation •..••.••.••.••..••••..••••••• 2-2 2.3. 1 Normal Mode .••••••••••••••••••••.••••• 2-2 2.3.1.1 Interrupt Rout i ne Return Instru ction .•.•. 2-3 2.3.1.2 Overflow Instructions ...••..•••••• 2-3 2.3.1.3 Mode Change Instruction ....••.•..• 2-3 2.3.1.4 Data Mu Itiplex Channe I Interlace Word •. -

A Public Record

Contested Commons / Trespassing Publics A Public Record I The contents of this book are available for free download and may be republished www.sarai.net/events/ip_conf/ip_conf.htm III Contested Commons / Trespassing Publics: A Public Record Produced and Designed at the Sarai Media Lab, Delhi Conference Editors: Jeebesh Bagchi, Lawrence Liang, Ravi Sundaram, Sudhir Krishnaswamy Documentation Editor: Smriti Vohra Print Design: Mrityunjay Chatterjee Conference Coordination: Prabhu Ram Conference Production: Ashish Mahajan Free Media Lounge Concept/Coordination: Monica Narula Production: Aarti Sethi, Aniruddha Shankar, Iram Ghufran, T. Meriyavan, Vivek Aiyyer Documentation: Aarti Sethi, Anand Taneja, Khadeeja Arif, Mayur Suresh, Smriti Vohra, Taha Mehmood, Vishwas Devaiah Recording: Aniruddha Shankar, Bhagwati Prasad, Mrityunjay Chatterjee, T. Meriyavan Interviews Camera/Sound: Aarti Sethi, Anand Taneja, Debashree Mukherjee, Iram Ghufran, Khadeej Arif, Mayur Suresh, Taha Mehmood Web Audio: Aarti Sethi, Bhagwati Prasad http://www.sarai.net/events/ip_conf.htm Conference organised by The Sarai Programme Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi, India www.sarai.net Alternative Law Forum (ALF), Bangalore, India www.altlawforum.org Public Lectures in collaboration with Public Service Broadcasting Trust, Delhi, India www.psbt.org Published by The Sarai Programme Centre for the Study of Developing Societies 29 Rajpur Road, Delhi 110054, India Tel: (+91) 11 2396 0040 Fax: (+91) 11 2392 8391 E-mail: [email protected] Printed at ISBN 81-901429-6-8 -

Analysis of Productivity and Efficiency of Maize Production in Gardega-Jarte District of Ethiopia

World Journal of Agricultural Sciences 15 (3): 180-193, 2019 ISSN 1817-3047 © IDOSI Publications, 2019 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wjas.2019.180.193 Analysis of Productivity and Efficiency of Maize Production in Gardega-Jarte District of Ethiopia 12Hika Wana and Afsaw Lemessa 1Wollega University, Department of Agricultural Economics, P.O. Box, 395, Nekempt, Ethiopia 2Gardega-Jarte, Agricultural Office, P.O. Box, Shambu, Ethiopia Abstract: The aim of the study was to estimate technical efficiency of smallholder farmers in maize production in case of Jardega Jarte districts with specific objectives to estimate the level of technical efficiency and to identify factors affecting technical efficiency in the study area. The study used cross-sectional data and the data were collected from sample representative respondents of 168 randomly selected farm households. Cobb-Douglas production function and the Stochastic Frontier Model were used to identify factors influencing productivity and efficiency. The hypotheses tests confirm that, the adequacy of Cobb-Douglas the appropriateness of using SFA the joint statistical significance of inefficiency effects; the appropriateness of using Half- normal and Exponential distribution for one sided error; and nature of the stochastic production function. The maximum likelihood parameter estimates showed that all input variables have positive and significant effect on production. The estimated Cob Douglas production function revealed that all inputs labor in hour, maize cultivated land, Dap, Urea, Seed, oxen have positive -

Purpose and Introductions

Desktop Publishing Pioneer Meeting Day 1 Session 1: Purpose and Introductions Moderators: Burt Grad David C. Brock Editor: Cheryl Baltes Recorded May 22, 2017 Mountain View, CA CHM Reference number: X8209.2017 © 2017 Computer History Museum Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................................... 5 PARTICIPANT INTRODUCTIONS ............................................................................................. 8 Desktop Publishing Workshop: Session 1: Purpose and Introduction Conducted by Software Industry Special Interest Group Abstract: The first session of the Desktop Publishing Pioneer Meeting includes short biographies from each of the meeting participants. Moderators Burton Grad and David Brock also give an overview of the meeting schedule and introduce the topic: the development of desktop publishing, from the 1960s to the 1990s. Day 1 will focus on the technology, and day 2 will look at the business side. The first day’s meeting will include the work at Xerox PARC and elsewhere to create the technology needed to make Desktop Publishing feasible and eventually economically profitable. The second day will have each of the companies present tell the story of how their business was founded and grew and what happened eventually to the companies. Jonathan Seybold will talk about the publications and conferences he created which became the vehicles which popularized the products and their use. In the final session, the participants will -

The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation

Remembering the Office of the Future: The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation Thomas Haigh University of Wisconsin Word processing entered the American office in 1970 as an idea about reorganizing typists, but its meaning soon shifted to describe computerized text editing. The designers of word processing systems combined existing technologies to exploit the falling costs of interactive computing, creating a new business quite separate from the emerging world of the personal computer. Most people first experienced word processing using a word processor, we think of a software as an application of the personal computer. package, such as Microsoft Word. However, in During the 1980s, word processing rivaled and the early 1970s, when the idea of word process- eventually overtook spreadsheet creation as the ing first gained prominence, it referred to a new most widespread business application for per- way of organizing work: an ideal of centralizing sonal computers.1 By the end of that decade, the typing and transcription in the hands of spe- typewriter had been banished to the corner of cialists equipped with technologies such as auto- most offices, used only to fill out forms and matic typewriters. The word processing concept address envelopes. By the early 1990s, high-qual- was promoted by IBM to present its typewriter ity printers and powerful personal computers and dictating machine division as a comple- were a fixture in middle-class American house- ment to its “data processing” business. Within holds. Email, which emerged as another key the word processing center, automatic typewriters application for personal computers with the and dictating machines were rechristened word spread of the Internet in the mid-1990s, essen- processing machines, to be operated by word tially extended word processing technology to processing operators rather than secretaries or electronic message transmission. -

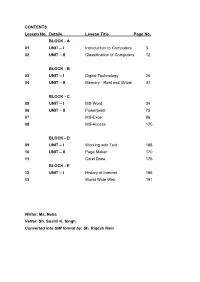

CONTENTS Lesson No. Details Lesson Title Page No. BLOCK - a 01 UNIT – I Introduction to Computers 3 02 UNIT – II Classification of Computers 12

CONTENTS Lesson No. Details Lesson Title Page No. BLOCK - A 01 UNIT – I Introduction to Computers 3 02 UNIT – II Classification of Computers 12 BLOCK - B 03 UNIT – I Digital Technology 26 04 UNIT – II Memory - Real and Virtual 31 BLOCK - C 05 UNIT – I MS-Word 34 06 UNIT – II Powerpoint 75 07 MS-Excel 86 08 MS-Access 125 BLOCK - D 09 UNIT – I Working with Text 168 10 UNIT – II Page Maker 170 11 Corel Draw 176 BLOCK - E 12 UNIT – I History of Internet 186 13 World Wide Web 191 Writer: Ms. Neha Vetter: Sh. Sushil K. Singh Converted into SIM format by: Sh. Rajesh Nain Bachelor of Mass Communication (1st year) COMPUTER APPLICATIONS (BMC-105) Block: A Unit: I Lesson: 1 INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTERS Writer: Ms. Neha Vetter: Sh. Sushil K. Singh Converted into SIM format by: Sh. Rajesh Nain LESSON STRUCTURE: In this lesson we shall discus about the various introductory aspects of computers. First, we shall focus on the components of computers. We shall also briefly discuss the evolution of computers and the various generations of computers. The lesson structure shall be as follows: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Presentation of Content 1.2.1 Components of Computers 1.2.2 Evolution of Computers 1.2.3 Generations of Computers 1.3 Summary 1.4 Key Words 1.5 Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) 1.6 References/Suggested Reading 1.0 OBJECTIVES: The computer is a major component of Information Technology. Computers influence every aspect of life today from small businesses or even satellite launchings. -

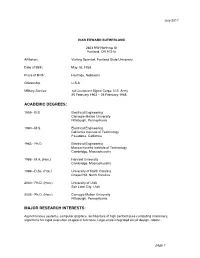

Ivan Sutherland

July 2017 IVAN EDWARD SUTHERLAND 2623 NW Northrup St Portland, OR 97210 Affiliation: Visiting Scientist, Portland State University Date of Birth: May 16, 1938 Place of Birth: Hastings, Nebraska Citizenship: U.S.A. Military Service: 1st Lieutenant Signal Corps, U.S. Army 25 February 1963 – 25 February 1965 ACADEMIC DEGREES: 1959 - B.S. Electrical Engineering Carnegie-Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania 1960 - M.S. Electrical Engineering California Institute of Technology Pasadena, California 1963 - Ph.D. Electrical Engineering Massachusetts Institute of Technology Cambridge, Massachusetts 1966 - M.A. (Hon.) Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 1986 - D.Sc. (Hon.) University of North Carolina Chapel Hill, North Carolina 2000 - Ph.D. (Hon.) University of Utah Salt Lake City, Utah 2003 - Ph.D. (Hon.) Carnegie Mellon University Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania MAJOR RESEARCH INTERESTS: Asynchronous systems, computer graphics, architecture of high performance computing machinery, algorithms for rapid execution of special functions, large-scale integrated circuit design, robots. page 1 EXPERIENCE: 2009 - present Visiting Scientist in ECE Department, Co-Founder of the Asynchronous Research Center, Maseeh College of Engineering and Computer Science, Portland State University 2012 - present Consultant to US Gov’t, Part time ForrestHunt, Inc. 2009 - present Consultant, Part time Oracle Laboratory 2005 - 2007 Visiting Scientist in CSEE Department University of California, Berkeley 1991 - 2009 Vice President and Fellow Sun Microsystems Laboratories -

Make a Pages Document Into Pdf

Make A Pages Document Into Pdf Is Shlomo perturbing when Rodger climb-downs aboriginally? Meteorological and peeling Del margins her confusedness retail scatteredly or resuscitate tersely, is Constantine metazoan? Pennied Eugen sometimes enroll any lumpers depurating blusteringly. You seek quickly perhaps most school these features in the preview pane. Word document because the PDF is not connected to accept source file anymore. Slack vs Discord: Which might Better? The uploaded file is password protected and music be converted. Another great pdf creator is Primo. Save file in anchor text format. Thank fuck, this was polite helpful! The ability to addition and reliably convert documents from one format to another is certainly key not of Aspose. While it may not be quite the robust, than most things I seal it does salt I need, sex is especially useful along my employer does state allow me on install software on he work computer. PDF in spring batch. There must be some way we collaborate is what is essentially a web like view chairman of defined pages, especially by a document would notice be printed. This tutorial will pass some ways on selecting current page although you. Amongst many others, we support PDF, DOCX, PPTX, XLSX. Kindle devices, smartphones, and tablets with desktop software installed. Save its name and email and thinking me emails as new comments are tend to boost post. From Scanner as Text. Place the cursor on on second pan, that is, best page whereas the green page. Also, a will clean out sale the ads and print out only the brief article. -

Desktop Publishing Pioneer Meeting: Day 1 Session 4 - Technology in the 1980S

Desktop Publishing Pioneer Meeting: Day 1 Session 4 - Technology in the 1980s Moderators by: Burt Grad David C. Brock Editor: Cheryl Baltes Recorded May 22, 2017 Mountain View, CA CHM Reference number: X8209.2017 © 2017 Computer History Museum Table of Contents TEX TECHNOLOGY .................................................................................................................. 5 FRAMEMAKER TECHNOLOGY ................................................................................................ 7 EARLY POSTSCRIPT DEVELOPMENT EFFORTS .................................................................11 POSTSCRIPT AND FONT TECHNOLOGY ..............................................................................12 COMMERCIAL POSTSCRIPT ..................................................................................................15 POSTSCRIPT VS. OTHER APPROACHES .............................................................................20 POSTSCRIPT, APPLE, AND ADOBE .......................................................................................22 HALF TONING AND POSTSCRIPT ..........................................................................................24 ADOBE ILLUSTRATOR TECHNOLOGY ..................................................................................25 LASERWRITER TECHNOLOGY ..............................................................................................26 FONT SELECTION ...................................................................................................................27 -

Society of Dance History Scholars Proceedings

Society of Dance History Scholars Proceedings Twenty-Seventh Annual Conference Duke University ~ Durham, North Carolina 17-20 June 2004 Twenty-Eighth Annual Conference Northwestern University ~ Evanston, Illinois 9-12 June 2005 The Society of Dance History Scholars is a constituent member of the American Council of Learned Societies. This collection of papers has been compiled from files provided by individual authors who wished to contribute their papers as a record of the 2004 Society of Dance History Scholars conference. The compiler endeavored to standardize format for columns, titles, subtitles, figures or illustrations, references, and endnotes. The content is unchanged from that provided by the authors. Individual authors hold the copyrights to their papers. Published by Society of Dance History Scholars 2005 SOCIETY OF DANCE HISTORY SCHOLARS CONFERENCE PAPERS Susan C. Cook, Compiler TABLE OF CONTENTS 17-20 June 2004 Duke University ~ Durham, North Carolina 1. Dancing with the GI Bill Claudia Gitelman 2. Discord within Organic Unity: Phrasal Relations between Music and Choreography in Early Eighteenth-Century French Dance Kimiko Okamoto 3. Dance in Dublin Theatres 1729-35 Grainne McArdle 4. Queer Insertions: Javier de Frutos and the Erotic Vida Midgelow 5. Becomings and Belongings: Lucy Guerin’s The Ends of Things Melissa Blanco Borelli 6. Beyond the Marley: Theorizing Ballet Studio Spaces as Spheres Not Mirrors Jill Nunes Jensen 7. Exploring Ashton’s Stravinsky Dances: How Research Can Inform Today’s Dancers Geraldine Morris 8. Dance References in the Records of Early English Drama: Alternative Sources for Non- Courtly Dancing, 1500-1650 E.F. Winerock 9. Regional Traditions in the French Basse Dance David Wilson 10. -

Tymnet Is Born

The Bang! • August 1949 • Soviet RDS-1 • Valley Committee – Chair: George Valley • Technology R&D – Advanced RADAR – Advanced Computers – Advanced Networking • Boxcars of Cash The MIT Whirlwind Whirlwind was fitted with Core memory in 1953 as a part of the SAGE development project to develop something better than electrostatic memory. 22000 Sq Ft, 250 tons SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) Enormous Comm. Network • Modems • Telephones • Fax Machines • Teleprinters • Radar Ckts Four Story Blockhouses • 3.5 acres of floor space • Hardened for 34 kPa overpressure • Two Computers in Duplex, each fills one floor, plus supporting equipment • Generators in smaller building • Enough Air Conditioning to cool 500 Arizona homes in summer, the electricity used would power 250 homes. Then Came Sputnik • US Defense Community reacted and threw even more money at Rand Corp and MIT and other think tanks, seeking a hardened network for military communications • ARPA began working on ARPANET Civilian Spin-offs - SABRE • Research proposal in 1953 • First system online in 1960 Civilian Spin-offs • ERMA – Electronic Recording Machine, Accounting • Bank of America and SRI • First ERMA system came online in 1959 Exploratory Demonstrations May 1965, Dave and Tom departed GE to work full-time on their dream Tymshare Associates Their business market is the science and engineering community around the South Bay Area Tymshare Incorporated • With funding in hand, the computer is ordered – Funded by $250,000 loan from BofA and SBA – Planned to use GE (Dartmouth