The Origins of Word Processing and Office Automation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Wang Laboratories 2200 Series

C21-908-101 Programmable Terminals Wang Laboratories 2200 Series MANAGEMENT SUMMARY A series of five minicomputer systems that Wang Laboratories' 2200 Series product line currently offer both batch and interactive communica consists of the 2200VP, 2200MVP, 2200LVP and tions capabilities. 2200SVP processors, all of which are multi-user or multi user upgradeable systems. The 2200 Series product line Emulation packages are provided for standard also includes the 2200 PCS-I1I, a packaged system which Teletype communications; IBM 2741 emula is single-user oriented. tion; IBM 2780, 3780, and 3741 batch terminal communications; and IBM 3270 The CPU and floppy disk drive are packaged together interactive communications. with appropriate cables and a cabinet to produce an integrated system. The 2200 PCS-I1I includes the CPU, A basic 2200PCS-1II with 32K bytes of user CRT, keyboard and single-sided double density memory, a CRT display, and a minidiskette minidiskette drive in a standard CRT-size enclosure as drive is priced at $6,500. Prices range well as an optional disk multiplexer controller. The upward to $21,000 for a 2200MVP proc number of peripherals that can be attached to a given essor with 256K bytes of user memory, system depends on the number of I/O slots that are excluding peripherals. Leases and rental plans available, with most peripherals requiring one slot. In all are also available. 2200 Series CPUs, highly efficient use of memory is achieved through the use of separate control memory to store the BASIC-2 interpreter and operating system. CHARACTERISTICS Wang began marketing the original 2200 Series in the VENDOR: Wang Laboratories,lnc., One Industrial Avenue, Spring of 1973. -

Word Processing Tool

WORD PROCESSING 3 TOOL Objectives I like the computer because it keeps giving you After completing this Chapter, the options. What if I do this? You try it, and if you student will be able to: don't like it you undo it. The original can always be resurrected. It raises the idea of working on • work with any word processing program, one painting your whole life, saving it and working on it again and again. • create, save and open a Elliott Green document using a word Research Associate and Tutorial Fellow, Oxford University processor, • format a document inserting bullets/numbering, tables, pictures, etc., Introduction • set custom tabs and apply styles, We have to submit a project as part of our course • prepare a document for printing, evaluation. We will perhaps take a chart paper • enhance the features of the and design the project, write a report and submit document inserting graphics, it to our teacher. That’s the way we have done it tables, pictures, charts, etc., and all along? Have we ever thought of typing the entire using different formatting styles, project report using a computer and submitting it • modify document using various in a nicely designed printed form? Ever reflected editing and formatting features on getting information from the Internet and within or across documents, presenting it neatly for the project? Now that’s • produce documents for various the way things are being done! And if we are already purposes and thinking of it, it’s time to discover some document creation software, i.e., word processing tool to get • apply mail merge facility to send a document to different the job done. -

Exploring Users' Perceptions and Expectations of Security

Cloudy with a Chance of Misconceptions: Exploring Users’ Perceptions and Expectations of Security and Privacy in Cloud Office Suites Dominik Wermke, Nicolas Huaman, Christian Stransky, Niklas Busch, Yasemin Acar, and Sascha Fahl, Leibniz University Hannover https://www.usenix.org/conference/soups2020/presentation/wermke This paper is included in the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security. August 10–11, 2020 978-1-939133-16-8 Open access to the Proceedings of the Sixteenth Symposium on Usable Privacy and Security is sponsored by USENIX. Cloudy with a Chance of Misconceptions: Exploring Users’ Perceptions and Expectations of Security and Privacy in Cloud Office Suites Dominik Wermke Nicolas Huaman Christian Stransky Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Niklas Busch Yasemin Acar Sascha Fahl Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Leibniz University Hannover Abstract respective systems. These dedicated office tools helped the Cloud Office suites such as Google Docs or Microsoft Office adoption of personal computers over more dedicated or me- 365 are widely used and introduce security and privacy risks chanical systems for word processing. In recent years, another to documents and sensitive user information. Users may not major shift is happening in the world of office applications. know how, where and by whom their documents are accessible With Microsoft Office 365, Google Drive, and projects like and stored, and it is currently unclear how they understand and LibreOffice Online, most major office suites have moved to mitigate risks. We conduct surveys with 200 cloud office users provide some sort of cloud platform that allows for collabo- from the U.S. -

8000 Plus Magazine Issue 17

THE BEST SELLIINIG IVI A<3 AZI INI E EOF=t THE AMSTRAD PCW Ten copies ofMin^g/jf^^ Office Professional to be ISSUE 17 • FEBRUARY 1988* £1.50 Could AMS's new desktop publishing package be the best yet? f PLUS: Complete buyer's guide to word processing, accounts, utilities and DTP software jgl- ) MASTERFILE 8000 FOR ALL AMSTRAD PCW COMPUTERS MASTERFILE 8000, the subject of so many Any file can make RELATIONAL references to up enquiries, is now available. to EIGHT read-only keyed files, the linkage being effected purely by the use of matching file and MASTERFILE 8000 is a totally new database data names. product. While drawing on the best features of the CPC versions, it has been designed specifically for You can import/merge ASCII files (e.g. from the PCW range. The resulting combination of MASTERFILE III), or export any data (e.g. to a control and power is a delight to use. word-processor), and merge files. For keyed files this is a true merge, not just an append operation. Other products offer a choice between fast but By virtue of export and re-import you can make a limited-capacity RAM files, and large-capacity but copy of a file in another key sequence. New data cumbersome fixed-length, direct-access disc files. fields can be added at any time. MASTERFILE 8000 and the PCW RAM disc combine to offer high capacity with fast access to File searches combine flexibility with speed. variable-length data. File capacity is limited only (MASTERFILE 8000 usually waits for you, not by the size of your RAM disc. -

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word

Microsoft Word 1 Microsoft Word Microsoft Office Word 2007 in Windows Vista Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.0.6425.1000 (2007 SP2) / April 28, 2009 Operating system Microsoft Windows Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [1] Website Microsoft Word Windows Microsoft Word 2008 in Mac OS X 10.5. Developer(s) Microsoft Stable release 12.2.1 Build 090605 (2008) / August 6, 2009 Operating system Mac OS X Type Word processor License Proprietary EULA [2] Website Microsoft Word Mac Microsoft Word is Microsoft's word processing software. It was first released in 1983 under the name Multi-Tool Word for Xenix systems.[3] [4] [5] Versions were later written for several other platforms including IBM PCs running DOS (1983), the Apple Macintosh (1984), SCO UNIX, OS/2 and Microsoft Windows (1989). It is a component of the Microsoft Office system; however, it is also sold as a standalone product and included in Microsoft Microsoft Word 2 Works Suite. Beginning with the 2003 version, the branding was revised to emphasize Word's identity as a component within the Office suite; Microsoft began calling it Microsoft Office Word instead of merely Microsoft Word. The latest releases are Word 2007 for Windows and Word 2008 for Mac OS X, while Word 2007 can also be run emulated on Linux[6] . There are commercially available add-ins that expand the functionality of Microsoft Word. History Word 1981 to 1989 Concepts and ideas of Word were brought from Bravo, the original GUI writing word processor developed at Xerox PARC.[7] [8] On February 1, 1983, development on what was originally named Multi-Tool Word began. -

A Public Record

Contested Commons / Trespassing Publics A Public Record I The contents of this book are available for free download and may be republished www.sarai.net/events/ip_conf/ip_conf.htm III Contested Commons / Trespassing Publics: A Public Record Produced and Designed at the Sarai Media Lab, Delhi Conference Editors: Jeebesh Bagchi, Lawrence Liang, Ravi Sundaram, Sudhir Krishnaswamy Documentation Editor: Smriti Vohra Print Design: Mrityunjay Chatterjee Conference Coordination: Prabhu Ram Conference Production: Ashish Mahajan Free Media Lounge Concept/Coordination: Monica Narula Production: Aarti Sethi, Aniruddha Shankar, Iram Ghufran, T. Meriyavan, Vivek Aiyyer Documentation: Aarti Sethi, Anand Taneja, Khadeeja Arif, Mayur Suresh, Smriti Vohra, Taha Mehmood, Vishwas Devaiah Recording: Aniruddha Shankar, Bhagwati Prasad, Mrityunjay Chatterjee, T. Meriyavan Interviews Camera/Sound: Aarti Sethi, Anand Taneja, Debashree Mukherjee, Iram Ghufran, Khadeej Arif, Mayur Suresh, Taha Mehmood Web Audio: Aarti Sethi, Bhagwati Prasad http://www.sarai.net/events/ip_conf.htm Conference organised by The Sarai Programme Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, Delhi, India www.sarai.net Alternative Law Forum (ALF), Bangalore, India www.altlawforum.org Public Lectures in collaboration with Public Service Broadcasting Trust, Delhi, India www.psbt.org Published by The Sarai Programme Centre for the Study of Developing Societies 29 Rajpur Road, Delhi 110054, India Tel: (+91) 11 2396 0040 Fax: (+91) 11 2392 8391 E-mail: [email protected] Printed at ISBN 81-901429-6-8 -

Analysis of Productivity and Efficiency of Maize Production in Gardega-Jarte District of Ethiopia

World Journal of Agricultural Sciences 15 (3): 180-193, 2019 ISSN 1817-3047 © IDOSI Publications, 2019 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.wjas.2019.180.193 Analysis of Productivity and Efficiency of Maize Production in Gardega-Jarte District of Ethiopia 12Hika Wana and Afsaw Lemessa 1Wollega University, Department of Agricultural Economics, P.O. Box, 395, Nekempt, Ethiopia 2Gardega-Jarte, Agricultural Office, P.O. Box, Shambu, Ethiopia Abstract: The aim of the study was to estimate technical efficiency of smallholder farmers in maize production in case of Jardega Jarte districts with specific objectives to estimate the level of technical efficiency and to identify factors affecting technical efficiency in the study area. The study used cross-sectional data and the data were collected from sample representative respondents of 168 randomly selected farm households. Cobb-Douglas production function and the Stochastic Frontier Model were used to identify factors influencing productivity and efficiency. The hypotheses tests confirm that, the adequacy of Cobb-Douglas the appropriateness of using SFA the joint statistical significance of inefficiency effects; the appropriateness of using Half- normal and Exponential distribution for one sided error; and nature of the stochastic production function. The maximum likelihood parameter estimates showed that all input variables have positive and significant effect on production. The estimated Cob Douglas production function revealed that all inputs labor in hour, maize cultivated land, Dap, Urea, Seed, oxen have positive -

IBM PC Club IBM PC Club

San Jose PC CI ub Newsletter Document Number SJPCN03 May 4, 1982 Edited by Bonnie Lamb F98/142 San Jose 8 + 276-3653 VM(SJEVMl/LAMB) IBM PC Club IBM PC Club CONTENTS IBM SAN JOSE PC NEWSLETTER 1 Errata 1 April Meeting . 2 Special Interest Groups (SIG) 3 Survey Results ....... 3 San Jose PC Club Profile 5 Tips and Techniques 6 Programming notes 8 Electrohome 1302 Color Monitor with the PC 11 VOLKSWRITER Comparison to EASYWRITER 12 PC Puzzler 14 I nstall Notes 16 PC Club Program Library Directory 17 PC Add-Ons .... 19 SORT Comparisons 20 Help Wanted/Help Offered 21 Classified 22 PC Newsletter Articles 23 ii SJPCN03 05/04/82 IBM PC Club IBM SAN JOSE PC NEWSLETTER This month's newsletter has some survey results, sort performance information, a crossword puzzle (don't peek at the answers), and other good stuff. Time is short, we should have gone to press yesterday, so I'll close with next month's activity schedule: DATE DAY TIME LOCATION EVENT May 11 Tue. 5 p.m. STL Cafeteria PC Club Meeting May 12 Wed. 7:30p.m. DYSAN Santa Clara SVCC May 18 Tue. 5 p.m. STL K210 Phototypsetting SIG May 25 Tue. 5 p.m. STL K210 Visiclub (SIG) Meeting June 1 Tue. 5 p.m. STL K210 Advisory Meeting ERRATA The Silicon Valley Computer Club (SVCC) has found a bug in the BIOS modification that was printed in SJPCNOI to allow double-sided floppies. Details of symptoms and a possible fix are in the works. Look in next month's newsletter for this in formation. -

E^SEBHC to Meet at HUGCON'87

2J Saving Onr HEATH Eight-Bit Machines! > Volume 1, Number 11 *2.50 a copy, *15.00 a rear June-July, 1987 E^SEBHC To Meet At HUGCON’87 =12 Full Two 1 SEBHC JOURNAL Volume 1, Number 11, Page 2 The Details The First Annual General Meeting of the Society of Heath Eight-Bit Com- puterists will be held at the Chicago O’Hare Hyatt Regency hotel some time during Friday, 21 August, 1987. Exact time and location will be displayed from noon, Friday on the hotel lobby information terminals. The Society presently is informal—no officers or committees—and the only "official office holder" is L.E. Geisler, editor and publisher of the SEBHC JOURNAL. In the remote possibility that some SEBHC members want to establish a formal society, we advise them to send a proposed outline of same to the SEBHC JOURNAL. We will publish all those received before 5- Aug-87 in issue number 12 (August, 1987). The August JOURNAL issue will be available in the meeting room from about 13:00, Friday. Interested members can read what others have proposed in this issue, and may then discuss the proposals with other members also attending. If desired, they can draft a formal proposal for establishing a government, constitution and bylaws for the Society BEFORE meeting and acting on Lhe proposal. Note: This meeting will be quite brief, as most members are expecting to attend HUGCON-VI, and we don’t want them missing that. Subscribers visiting the meeting room may pick up their Aug-87 copy of the SEBHC JOURNAL there. -

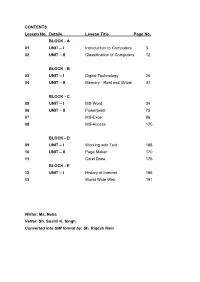

CONTENTS Lesson No. Details Lesson Title Page No. BLOCK - a 01 UNIT – I Introduction to Computers 3 02 UNIT – II Classification of Computers 12

CONTENTS Lesson No. Details Lesson Title Page No. BLOCK - A 01 UNIT – I Introduction to Computers 3 02 UNIT – II Classification of Computers 12 BLOCK - B 03 UNIT – I Digital Technology 26 04 UNIT – II Memory - Real and Virtual 31 BLOCK - C 05 UNIT – I MS-Word 34 06 UNIT – II Powerpoint 75 07 MS-Excel 86 08 MS-Access 125 BLOCK - D 09 UNIT – I Working with Text 168 10 UNIT – II Page Maker 170 11 Corel Draw 176 BLOCK - E 12 UNIT – I History of Internet 186 13 World Wide Web 191 Writer: Ms. Neha Vetter: Sh. Sushil K. Singh Converted into SIM format by: Sh. Rajesh Nain Bachelor of Mass Communication (1st year) COMPUTER APPLICATIONS (BMC-105) Block: A Unit: I Lesson: 1 INTRODUCTION TO COMPUTERS Writer: Ms. Neha Vetter: Sh. Sushil K. Singh Converted into SIM format by: Sh. Rajesh Nain LESSON STRUCTURE: In this lesson we shall discus about the various introductory aspects of computers. First, we shall focus on the components of computers. We shall also briefly discuss the evolution of computers and the various generations of computers. The lesson structure shall be as follows: 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Presentation of Content 1.2.1 Components of Computers 1.2.2 Evolution of Computers 1.2.3 Generations of Computers 1.3 Summary 1.4 Key Words 1.5 Self-Assessment Questions (SAQs) 1.6 References/Suggested Reading 1.0 OBJECTIVES: The computer is a major component of Information Technology. Computers influence every aspect of life today from small businesses or even satellite launchings. -

Published In: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, Vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), Pp

Published in: Encyclopedia of Library and Information Science, vol. 49 (New York: Dekker, 1992), pp. 268-78 Author’s address: [email protected] WORD PROCESSING (HISTORY OF). Definition. The term and concept of “word processing” are by now so widely used that most readers will be already familiar with them. The term, created on the model of “data processing,” is more vague than commonly believed. A human editor, for example, obviously pro- cesses words, but is not what is meant by a “word proces- sor.” A number of software programs process words in one way or another--a concordance or indexing program, for example--but are not understood to be word processing programs.’ The term “word processor” means a facility that records keystrokes from a typewriter-like keyboard, and prints the output onto paper in a separate operation. In the meantime the data is stored, usually in memory or mag- netic media. A word processor also can make improve- ments in the stream of words before they are printed. At their most basic these include the ability to arrange words into lines. An “editor,” such as the infamous EDLINE distributed with the Microsoft Disk Operating System (MS-DOS), lacks the ability to structure lines. Commonly a word processor is understood to be a software program, and in the 1980s and 1990s it usually meant a program written for a microcomputer. However, preceding this period and continuing through it there have been hardware word processors. These are pieces of equip- ment sold for the sole purpose of word processing, con- taining in one package a keyboard, printer, recording and playback device, and in all recent examples a video or liquid crystal display screen. -

Instructions to the Students: Outlines: Understanding Word Processing Program

Karary University – Dr. Abdeldime Mohamed Salih – Lecture Note College of Medicine Lecture Two Title: Dealing With Word Processing Programs Instructions to the Students: By the end of this lecture readers will be familiar with Microsoft word usages. Before start: You need to use your own computer to practice the following skills The following note is prepared to understanding how to deal with the computer in general. Further information can be found at the reference given in the content of the subject. Also you can find more information in the internet. The content is prepared in such way that suits the pharmacy college students to help them dealing with Microsoft word. Also you contact the instructor in his office any time between 12:00 to 2:00 Word processing programs are constantly evolving. Try to keep as up-to-date as possible by reading computer-related news, blogs, RSS feeds, newsletters, forums, and following computer people on social networking sites. Micrsoft word is a very good tool for word processing and editing documents and has many properties that would help and you need to practice, practice, and practice! Outlines: 1. Understanding word processing Program 2. Word Processing Programs 3. Microsoft word 4. Some tips for saving time when using Microsoft word 5. Some exercises Understanding word processing Program In the past, the word processor was a device that provides for formatting and output of text, often with some additional features. Early word processors were stand-alone devices dedicated to this function, but current word processors are word processor programs running on general purpose computers to input, editing, formatting text.