The Impacts of Resettlement on Funeral Custom Among the San in New Xade, Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A

REPORT TO THE MINISTER FOR PRESIDENTIAL AFFAIRS, GOVERNANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ON THE 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS I REPORT Honourable Justice Abednego B. Tafa Mr. John Carr-Hartley Members of CHAIRMAN DEPUTY CHAIRMAN The Independent Electoral Commission Mrs. Agnes Setlhogile Mrs. Shaboyo Motsamai Dr. Molefe Phirinyane COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER Mrs. Martha J. Sayed Vacant COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A. Zuze Doreen L. Serumula SECRETARY DEPUTY SECRETARY Executive Management of the Secretariat Keolebogile M. Tshitlho Dintle S. Rapoo SENIOR MANAGER MANAGER CORPORATE SERVICES ELECTIONS AFFAIRS & FIELD OPERATIONS Obakeng B. Tlhaodi Uwoga H. Mandiwana CHIEF STATE COUNSEL MANAGER HUMAN RESOURCE & ADMINISTRATION 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT III Strategic Foundations ........................................................................................................................... I Members of The Independent Electoral Commission ................................................ II Executive Management of the Secretariat........................................................................... III Letter to The Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration ............................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................. 2 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... -

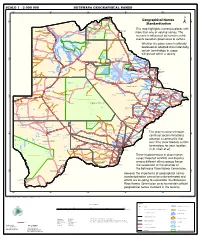

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

'Improving Their Lives.' State Policies and San Resistance in Botswana

Western University Scholarship@Western Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi) 2005 ‘Improving their lives.’ State policies and San resistance in Botswana Sidsel Saugestad Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Citation of this paper: Saugestad, Sidsel, "‘Improving their lives.’ State policies and San resistance in Botswana" (2005). Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi). 191. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/191 ‘Improving their lives.’ State policies and San resistance in Botswana Sidsel Saugestad Department of Social Anthropology, University of Tromso, N- 9037, Tromsø, Norway [email protected] Keywords San, Botswana, game reserve, relocation, indigenous peoples, land claim Abstract A court case raised by a group of San (former) hunter-gatherers, protesting against relocation from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, has attracted considerable international attention. The Government of Botswana argues that the relocation was done in order to ‘improve the lives’ of the residents, and that it was in their own best interest. The residents plead their right to stay in their traditional territories, a right increasingly acknowledged in international law, and claim that they did not relocate voluntarily. The case started in 2004 and will, due to long interspersed adjournments, go on into 2006. This article traces the events that led up to the case, and reports on its progress thus far. The case is seen as an arena for expressing and negotiating the relationship between an indigenous minority and the state in which they reside. -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117 -

Botswana: Trans-Kgalagadi Road Project

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP OPERATIONS EVALUATION DEPARTMENT (OPEV) Botswana: Trans-Kgalagadi Road Project PROJECT PERFORMANCE EVALUATION REPORT (PPER) PROJECT AND PROGRAM EVALUATION DIVISION (OPEV.1) May 2011 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 TRANS-KGALAGADI ROAD PROJECT .............................................................................................. 12 1.1 Country and Sector Context ...................................................................................................... 12 1.2 Project Formulation ................................................................................................................. 14 1.3 Objectives and Scope at Appraisal (Logical Framework) ............................................................. 14 1.4 Financing Arrangements – Bank and Others ............................................................................... 15 1.5 Evaluation Methodology and Approach ..................................................................................... 15 1.6 Key Performance Indicators and Availability of Baseline Data .................................................... 16 2 IMPLEMENTATION PERFORMANCE ................................................................................................ 16 2.1 Procurement and Contractors .................................................................................................... 16 2.2 Loan Effectiveness, Start-Up and Implementation ...................................................................... 16 2.3 Adherence to Project Time -

ASSESSMENT REPORT Complaint Regarding IFC's Investment In

ASSESSMENT REPORT Complaint Regarding IFC’s investment in Kalahari Diamonds Ltd, Botswana June 2005 Office of the Compliance Advisor/Ombudsman International Finance Corporation/ Multilateral Investment Guarantee Agency TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Acronyms …....................................................................................................................... ii Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 1 The Complaint………………. ........................................................................................................ 1 Background……............................................................................................................................ 2 Figure 1: Map Showing Prospecting Licenses Held by Sekaka Diamonds ….............................. 4 Assessment Findings……............................................................................................................. 5 Issue 1: Has IFC ensured that its client undertook proper consultation and complied with IFC’s policy pertaining to indigenous peoples? ..................................................................................... 5 CAO Findings……............................................................................................................. 7 CAO Recommendations…................................................................................................ 8 Issue 2: Was the pre-emptive dislocation of the San people from the -

The Challenges of Change: a Tracer Study of San Preschool Children in Botswana

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 463 848 PS 030 260 AUTHOR le Roux, Willemien TITLE The Challenges of Change: A Tracer Study of San Preschool Children in Botswana. Early Childhood Development: Practice and Reflections. Following Footsteps. INSTITUTION Bernard Van Leer Foundation, The Hague (Netherlands). REPORT NO No-15 ISBN ISBN-90-6195-062-7 ISSN ISSN-1382-4813 PUB DATE 2002-02-00 NOTE 115p.; Funding provided by UNICEF Botswana. For number 14 in this series, see ED 462 143. AVAILABLE FROM Bernard van Leer Foundation, P.O. Box 82334, 2508 EH, The Hague, Netherlands. Tel: 31-70-3512040; Fax: 31-70-3502373; e-mail: [email protected]; Web site: http://www.bernardvanleer.org. PUB TYPE Books (010)-- Reports Evaluative (142)-- Tests/Questionnaires (160) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC05 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Academic Achievement; Comparative Analysis; Corporal Punishment; *Culturally Relevant Education; Developing Nations; Dropouts; Followup Studies; Foreign Countries; Intervention; *Minority Groups; Outcomes of Education; Parent Attitudes; *Parents; *Primary Education; Program Descriptions; Social Change; Student Adjustment; Teacher Attitudes; *Young Children IDENTIFIERS Botswana; *San People ABSTRACT This report details findings of a study undertaken during 1993-1995 in the Ghanzi District of Botswana to ascertain the progress of the San children in primary school, comparing children who attended preschool to those who did not. The report also describes the Bokamoso Preschool Programme, started in 1986. Data for the study were collected through interviews with San parents and questionnaires and interviews with primary school teachers. Findings focus attention on the difficulties of the San people in responding to current demands that they earn a livelihood through agriculture rather than through traditional hunting and gathering practices. -

Report of the African Commission's Working Group on Indigenous

REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION’S WORKING GROUP ON INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS/COMMUNITIES MISSION TO THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA 15 – 23 June 2005 The African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights adopted this report at its 38th Ordinary Session, 21 November – 5 December 2005 2008 AFRICAN COMMISSION INTERNATIONAL ON HUMAN AND WORK GROUP FOR PEOPLES’ RIGHTS INDIGENOUS AFFAIRS REPORT OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION’S WORKING GROUP ON INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS/COMMUNITIES: MISSION TO THE REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA, 15 – 23 JUNE 2005 © Copyright: ACHPR and IWGIA Typesetting: Uldahl Graphix, Copenhagen, Denmark Prepress and Print: Litotryk, Copenhagen, Denmark ISBN: 9788791563294 Distribution in North America: Transaction Publishers 390 Campus Drive / Somerset, New Jersey 08873 www.transactionpub.com African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (ACHPR) Kairaba Avenue - P.O.Box 673, Banjul, The Gambia Tel: +220 4377 721/4377 723 - Fax: +220 4390 764 [email protected] - www.achpr.org International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs Classensgade 11 E, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark Tel: +45 35 27 05 00 - Fax: +45 35 27 05 07 [email protected] - www.iwgia.org This report has been produced with financial support from the Danish Ministry of Foreign Affairs TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS ...............................................................................................................................................6 - 7 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ............................................................................................................................... -

General Assembly Distr

UNITED NATIONS A General Assembly Distr. GENERAL A/HRC/15 22 February 2010 Original: ENGLISH HUMAN RIGHTS COUNCIL Fifteenth session Agenda item PROMOTION AND PROTECTION OF ALL HUMAN RIGHTS, CIVIL, POLITICAL, ECONOMIC, SOCIAL AND CULTURAL RIGHTS, INCLUDING THE RIGHT TO DEVELOPMENT Report by the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, James Anaya Addendum THE SITUATION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLES IN BOTSWANA ADVANCED UNEDITED VERSION A/HRC/15 page 2 Summary In this report, the Special Rapporteur on the situation of human rights and fundamental freedoms of indigenous people, Professor S. James Anaya, presents his observations and recommendations on the situation of indigenous peoples in Botswana, focusing on those groups that have been historically marginalized and remain non- dominant parts of society. This report arises out of an exchange of information with the Government, indigenous peoples, and other interested parties and follows the Special Rapporteur’s visit to Botswana between 19 and 27 March 2009. The Special Rapporteur acknowledges the initiatives undertaken by the Government of Botswana to address the conditions of disadvantaged indigenous peoples. The Special Rapporteur highlights, in particular, efforts aimed at addressing long-standing problems such as marginalization in political spheres and a history of under-development. Nonetheless, the Special Rapporteur notes that, while important, these initiatives still suffer from a variety of shortcomings and need to be designed and implemented in a manner that recognizes and respects cultural diversity and distinct indigenous or tribal identities. The Special Rapporteur notes that the Government of Botswana has developed a number of programmes aimed at preserving and celebrating the unique cultural attributes of the country’s many indigenous tribes. -

Ghanzi Sub District

GHANZI SUB DISTRICT VOL 10.0 GHANZI SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities 3 i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Ghanzi Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Ghanzi Sub District 3ii Table of Contents Preface 3 GHANZI SUB DISTRICT: Population and Housing Census 2011 1.0 Background and Commentary 7 Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities 1.1 Background to the Report 7 VOL 10.0 1.2 Importance of the Report 7 2.0 Total Population and growth 7 GHANZI/CENTRAL KALAHARI GAME RESERVE 3.0 Population Composition 8 3.1 Youth 8 Published by 3.2 The elderly 8 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 4.0 Population Growth 8 Phone: (267)3671300, 5.0 Population Projections 9 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 6.0 Orphan-hood 9 Website: www.cso.gov.bw 7.0 Literacy Levels 10 8.0 Disability 10 9.0 Religion 11 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 10.0 Marital Status 11 11.0 Labour Force and employment 12 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 12.0 Household Size 13 13.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 13 13.1 Access to Portable Water 13 13.2 Access to Improved Sanitation 14 ISBN: 978-99968-429-6-2 14.0 Source Energy for Lighting 14 14.1 Source of Energy for Cooking 14 14.2 Source of Energy for Heating 15 Annexes 16 1 iii 4 Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Ghanzi Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Ghanzi Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP FOR GHANZI DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

Government Gazette

REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA GOVERNMENT GAZETTE Vol. XXXVI, No. 69 GABORONE 31st December, 1998 CONTENTS Page Acting Appointment — : PermanentSecretary (Development), Office of the President — G.N. No. 471 Of 1998.....ccccccccccccccccccscecececesee 3736 Attorney-General — G.N. No. 472 of 1998.... 3736 Attorney-General — G.N. No. 473 of 1998..... 3736 Auditor-General — G.N. No. 474 Of 1998.00. eececccccsessessessesessessessesssesssscsusscssesscaversavssnsavareassusasatsreaanearens 3737 Administrative Secretary —G.N. No. 475 Of 1998......ccccccccessssssesssessesssecssesssessvssvessucssssevereserscssessuesisesesseseseeeses 3737 Secretary for Foreign Affairs — G.N. No. 476 of 1998..... 3737 Secretary for Foreign Affairs — G.N. No. 477 of 1998. 3738 Secretary for Foreign Affairs —G.N. No. 478 of 1998......c.ccccseeeeee 3738 PermanentSecretary, Ministry of Minerals, Energy and Water Affairs — G.N. No. 479 of 1998.. 3738 PermanentSecretary, Ministry of Labour and HomeAffairs — G.N. No. 480of 1998.........c:c0..+. 3739 PermanentSecretary, Ministry of Local Government, Lands and Housing —G.N. No.481 of 1998.....c:..ssse++. 3739 Application for Road Transport Permits—P—Permits — G.N. No. 482 of 1998 v...ccccceccssscssssessessseeseeeeees 3739—3740 Changein the Establishment of Schools — G.N. No. 483 Of 1998 .....cccccsscssscsssessesssessessvessessesssessesstessessussvessecsvessees 3740 Unclaimed Motor Vehicles — G.N. No. 484 of 1998 (First Publication) .......ccccccccccssssecsecesesssesesesessesesveseeceveseeeeees 3741 Public Notices ........c.ccccccess cess ess esssessesseesessecsnsesnessssssesuesssesssessearersscssesseesrssicsssesseesesessseses »-3742—3777 The following Supplementsare published with this issue of the Gazette — Supplement A — Botswana College of Distance and Open Learning Act, 1998 — Act NO. 20 Of 1908 ie eeeeea snaecocnnsereneeereseesepnpgumaesAl 159-167 ConsumerProtection Act, 1998 — Act No. 21 of 1998. 7 Vocational Training Act, 1998 — Act No.22of 1998...... Worker’s Compensation Act, 1998 — Act 23 of 1998............