An Equitable Framework for Antiretroviral Therapy and COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation Strategies in Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

WELLFIELD ·I I

"~), ~ ',0 )/)'./ iiJ G./) / .,' it-3~" - - ' REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION (TB 10/2/12/92-93) DRAFT TECHNICAL REPORT T9: SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUGUST 1995 Prepared by = ~.-~~.. INTER WELLFIELD ·i i,.. CO'ISULT in association with BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Keyworth, Nottingham, UK MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION Technical Report T9 August 1995 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Usable potable water supplies are limited to the Matsheng village areas. Economic fresh water supplies identified during recent groundwater investigations are located in village areas of Lokgwabe and Lehututu. Brackish water supplies identified outside the village areas are not available for use by livestock using communal grazing areas as they are either in areas already occupied or in areas with other land use designations. 2. No significant usable water supplies were identified in the communal grazing areas through the MAGI programme, and based on the available geophysical evidence, the chances of striking groundwater supplies for livestock in Matsheng communal areas are poor. 3. Total water consumption in the Matsheng area during the past year (to May 1995) is estimated at 254,200m' (697 m' per day). Of this amount about 150,000 m' (60%) are consumed by livestock watered at about 150 wells, boreholes and dams on pans. 4. Matsheng village households using public standpipes consume about 670 litres per household per week, or 20 litres per person per day (67% of the 30 litre DWA standard rate for rural village standpipe users). Residents of the four RAD settlements served by council bowsers received a ration of about 7 litres per person per day, or just 23% of the DWA standard. -

2017 SEAT Report Jwaneng Mine

JWANENG MINE SEAT 3REPORT 2017 - 2020 Contents INTRODUCTION TO JWANENG MINE’S SEAT 14 EXISTING SOCIAL PERFORMANCE 40 1. PROCESS 4. MANAGEMENT ACTIVITIES 1.1. Background and Objectives 14 4.1. Debswana’s Approach to Social Performance 41 and Corporate Social Investment 1.2. Approach 15 4.1.1. Approach to Social Performance 41 1.3. Stakeholders Consulted During SEAT 2017 16 4.1.2. Approach to CSI Programmes 41 1.4. Structure of the SEAT Report 19 4.2. Mechanisms to Manage Social Performance 41 2. PROFILE OF JWANENG MINE 20 4.3. Ongoing Stakeholder Engagement towards 46 C2.1. Overview of Debswana’s Operational Context 20 Social Performance Management 2.2. Overview of Jwaneng Mine 22 DELIVERING SOCIO-ECONOMIC BENEFIT 49 2.2.1. Human Resources 23 5. THROUGH ALL MINING ACTIVITIES 2.2.2. Procurement 23 5.1. Overview 50 2.2.3. Safety and Security 24 5.2. Assessment of Four CSI/SED Projects 52 2.2.4. Health 24 5.2.1. The Partnership Between Jwaneng Mine 53 Hospital and Local Government 2.2.5. Education 24 5.2.2. Diamond Dream Academic Awards 54 2.2.6. Environment 25 5.2.3. Lefhoko Diamond Village Housing 55 2.3. Future Capital Investments and Expansion 25 Plans 5.2.4. The Provision of Water to Jwaneng Township 55 and Sese Village 2.3.1. Cut-8 Project 25 5.3. Assessing Jwaneng Mine’s SED and CSI 56 2.3.2. Cut-9 Project 25 Activities 2.3.3. The Jwaneng Resource Extension Project 25 SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC IMPACTS 58 (JREP) 6. -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

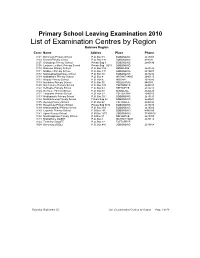

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Botswana Journal of Agriculture & Applied Sciences

Bots. J. Agric. Appl. Sci. (2014)10 (Issue 1) 3-10 Botswana Journal of Agriculture & Applied Sciences Leading Agriculture through Science and Innovation Please cite this article as: Kayombo, B. Tsheko, R. Semetsa, S and Malepa, D. (2014) Documentation of indigenous knowledge & best–bet practices on use of animals & plants for sustainable natural resource management in Botswana. Botswana Journal of Agriculture and Applied Sciences 10 (issue 1) (3-10) The online version of this article is located on the World Wide Web at: http://www.ub.bw/ojs/index.php/bojaas The views expressed in this article are that of the author(s) and not the publisher. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use or misuse of this material. This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. Kayombo et al 2014 Indigenous knowledge on the use of animals and plants. Bots. J. Agric. Appl. Sci. 10 (Issue 1) 3-10 ORIGINAL RESEARCH Documentation of indigenous knowledge and best-bet practices on the use of animals and plants for sustainable natural resources management in Botswana Kayombo, B.*1, Tsheko, -

Refundable Fee of P280.00 (Two Hundred and Eighty Pula Only) VAT Inclusive

PUBLIC TENDER NOTICE TENDER NO: BOCRA/PT/006/2020.2021 SUPPLY, INSTALLATION AND COMMISSIONING OF ICT EQUIPMENT AT TWELVE (12) TRIBAL ADMINISTRATIONS IN KWENENG DISTRICT The Botswana Communications Regulatory Authority (BOCRA or the Authority) hereby invites experienced and reputable companies to tender for the Supply, Installation and Commissioning of ICT Equipment at twelve (12) Tribal Administrations in Kweneng District. The tender is reserved for 100% citizen-owned companies who are registered with the Public Procurement and Asset Disposal Board (PPADB) under the following codes and subcodes; Code 203: Electrical, Electronic, Mechanical and ICT Supplies Subcode 01: Electrical and Electronic Equipment, Spares and Accessories (includes ICT, photographic equipment, and others). Youth owned companies in Botswana shall purchase the ITT at 50% of the purchase price as per Presidential Directive CAB 14 (B)/2015. The Invitation to Tender (ITT) document may be purchased at the BOCRA Head Office by interested companies at a non-refundable fee of P280.00 (Two Hundred and Eighty Pula Only) VAT inclusive. Payment must be made in the form of bank transfer or deposits to the following bank details: Bank Name: First National Bank Botswana Ltd Branch Name: Mall Branch Code: 28-28-67 Account Name: Botswana Communications Regulatory Authority Bank Account No: 62011115088 Swift Code: FIRNBWGX Reference: BTA0001 Tender documents shall be issued upon provision of Proof of Payment (POP). All funds transfer bank charges shall be borne by the bidder. Compulsory -

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization

Land Tenure Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization. Item Type text; Electronic Dissertation Authors Ijagbemi, Bayo, 1963- Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 06/10/2021 17:13:55 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/196133 LAND TENURE REFORMS AND SOCIAL TRANSFORMATION IN BOTSWANA: IMPLICATIONS FOR URBANIZATION by Bayo Ijagbemi ____________________ Copyright © Bayo Ijagbemi 2006 A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2006 2 THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA GRADUATE COLLEGE As members of the Dissertation Committee, we certify that we have read the dissertation prepared by Bayo Ijagbemi entitled “Land Reforms and Social Transformation in Botswana: Implications for Urbanization” and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Thomas Park _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Stephen Lansing _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr David Killick _______________________________________________________________________ Date: 10 November 2006 Dr Mamadou Baro Final approval and acceptance of this dissertation is contingent upon the candidate’s submission of the final copies of the dissertation to the Graduate College. I hereby certify that I have read this dissertation prepared under my direction and recommend that it be accepted as fulfilling the dissertation requirement. -

The Inconvenient Indigenous

1 SIDSEL SAUGESTAD The Inconvenient Indigenous Remote Area Development in Botswana, Donor Assistance, and the First People of the Kalahari The Nordic Africa Institute, 2001 2 The book is printed with support from the Norwegian Research Council. Front cover photo: Lokalane – one of the many small groups not recognised as a community in the official scheme of things Back cover photos from top: Irrigation – symbol of objectives and achievements of the RAD programme Children – always a hope for the future John Hardbattle – charismatic first leader of the First People of the Kalahari Ethno-tourism – old dance in new clothing Indexing terms Applied anthropology Bushmen Development programmes Ethnic relations Government policy Indigenous peoples Nation-building NORAD Botswana Kalahari San Photos: The author Language checking: Elaine Almén © The author and The Nordic Africa Institute 2001 ISBN 91-7106-475-3 Printed in Sweden by Centraltryckeriet Åke Svensson AB, Borås 2001 3 My home is in my heart it migrates with me What shall I say brother what shall I say sister They come and ask where is your home they come with papers and say this belongs to nobody this is government land everything belongs to the State What shall I say sister what shall I say brother […] All of this is my home and I carry it in my heart NILS ASLAK VALKEAPÄÄ Trekways of the Wind 1994 ∫ This conference that I see here is something very big. It can be the beginning of something big. I hope it is not the end of something big. ARON JOHANNES at the opening of the Regional San Conference in Gaborone, October 1993 4 Preface and Acknowledgements The title of this book is not a description of the indigenous people of Botswana, it is a characterisation of a prevailing attitude to this group. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

Kgatleng SUB District

Kgatleng SUB District VOL 5.0 KGATLENG SUB DISTRICT Population and Housing Census 2011 Selected Indicators for Villages and Localities ii i Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 3 Table of Contents Kgatleng Sub District Population And Housing Census 2011: Selected Indicators For Villages And Localities Preface 3 VOL 5,0 1.0 Background and Commentary 6 1.1 Background to the Report 6 Published by 1.2 Importance of the Report 6 STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone 2.0 Population Distribution 6 Phone: (267)3671300, 3.0 Population Age Structure 6 Fax: (267) 3952201 Email: [email protected] 3.1 The Youth 7 Website: www.cso.gov.bw/cso 3.2 The Elderly 7 4.0 Annual Growth Rate 7 5.0 Household Size 7 COPYRIGHT RESERVED 6.0 Marital Status 8 7.0 Religion 8 Extracts may be published if source is duly acknowledged 8.0 Disability 9 9.0 Employment and Unemployment 9 10.0 Literacy 10 ISBN: 978-99968-429-7-9 11.0 Orphan-hood 10 12.0 Access to Drinking Water and Sanitation 10 12.1 Access to Portable Water 10 12.2 Access to Sanitation 11 13.0 Energy 11 13.1 Source of Fuel for Heating 11 13.2 Source of Fuel for Lighting 12 13.3 Source of Fuel for Cooking 12 14.0 Projected Population 2011 – 2026 13 Annexes 14 iii Population and Housing Census 2011 [ Selected indicators ] Kgatleng Sub District Population and Housing Census 2011 [Selected Indicators] Kgatleng Sub District 1 FIGURE 1: MAP OF KATLENG DISTRICT Preface This report follows our strategic resolve to disaggregate the 2011 Population and Housing Census report, and many of our statistical outputs, to cater for specific data needs of users. -

2009 Primary Directory

2009 PRIMARY SCHOOLS DIRECTORY WITH SOME STATISTICAL DATA No. Nane of sch Address Tel Fax Ownership Region Inspectoral Inspc Officer/Ccontact Regional Officer/Contact District council Roll Boys Roll Girls Total Ro Teachers Southern West- 1 Acacia Bag 2 Jwaneng 5884807 5881525 Private South Jwaneng Mr. Lethosa - Tel: 5802300 T. Mokwena, 5440722 Southern 177 187 364 31 Central 2 Adelaide Box 5151 Serowe 4635576 0 Private South Serowe South Mrs. Malefho - Tel: 4600553 G.B. Smile, 4631635 Central 144 175 319 16 Southern West- 3 Adult Edu. Centre Private South Jwaneng Mr. Lethosa - Tel: 5802302 T. Mokwena, 5440724 Southern 8 33 41 1 4 Aerodrome Box 718 F/Town 2404202 2404203 Council North F/Town S. Thabano - Tel: 2412266 Mrs. E. Maswikiti, 2415075 Francistown 396 389 785 27 Central 5 Agosi Box 1673 0 Council South Bobirwa Ms Elias - Tel: 2619335 G.B Smile, 4630626 Central 183 195 378 17 South 6 Al-Haq Box 1543 Molepolole 5920762 4633215 Private Central Kweneng C Tel: 5921305 Mack, 3972454 Kweneng 137 119 256 16 South 7 Al-Nur Box 78 Gaborone 3974974 3972905 Private Central Gabs North Mr. Thibelang - Tel: 3972454 K. Mack, 3972454 Gaborone 180 200 380 24 Mr. Mathumo - Tel: 8 Andrew Wellio Council West Maun Mr. B.K. Habana - 6865317 6865317 North West 299 279 578 17 South 9 Anne-Stine 5921127 Private Central Kweneng C Tel: 5921305 K. Mack, 3972455 Kweneng 15 11 26 3 South 10 Artesia Box 3 Artesia 5728225 0 Council Central Kgatleng West Ms. Mosweunyane - Tel: 5777226 K. Mack, 3972454 Kgatleng 204 200 404 16 Central GG Moepeng, 11 Baipidi Box 315 Maun 6868016 0 Council North Boteti Mr. -

E-Government and Democracy in Botswana: Observational and Experimental Evidence on the Effects of E-Government Usage on Political Attitudes

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics Bante, Jana et al. Working Paper E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021 Provided in Cooperation with: German Development Institute / Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn Suggested Citation: Bante, Jana et al. (2021) : E-government and democracy in Botswana: Observational and experimental evidence on the effects of e-government usage on political attitudes, Discussion Paper, No. 16/2021, ISBN 978-3-96021-153-2, Deutsches Institut für Entwicklungspolitik (DIE), Bonn, http://dx.doi.org/10.23661/dp16.2021 This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/234177 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte.