UNIVERSITY of LONDON THESIS Degree P U I^ Year 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sourceone Search User Guide CONTENTS

SourceOne Search Version 7.2 SP9 User Guide REV 01 February 2020 Copyright © 2005-2020 Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries All rights reserved. Dell believes the information in this publication is accurate as of its publication date. The information is subject to change without notice. THE INFORMATION IN THIS PUBLICATION IS PROVIDED “AS-IS.” DELL MAKES NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND WITH RESPECT TO THE INFORMATION IN THIS PUBLICATION, AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIMS IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. USE, COPYING, AND DISTRIBUTION OF ANY DELL SOFTWARE DESCRIBED IN THIS PUBLICATION REQUIRES AN APPLICABLE SOFTWARE LICENSE. Dell Technologies, Dell, EMC, Dell EMC and other trademarks are trademarks of Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries. Other trademarks may be the property of their respective owners. Published in the USA. Dell EMC Hopkinton, Massachusetts 01748-9103 1-508-435-1000 In North America 1-866-464-7381 www.DellEMC.com 2 SourceOne Search User Guide CONTENTS Preface 7 Chapter 1 Getting Started 11 Accessing Dell EMC SourceOne Search............................................................ 12 Logging in to Dell EMC SourceOne Search........................................................12 About logging in and user authentication.............................................. 12 Specifying a domain..............................................................................12 UPN Support........................................................................................ 13 Limitations and considerations..............................................................13 -

African Names and Naming Practices: the Impact Slavery and European

African Names and Naming Practices: The Impact Slavery and European Domination had on the African Psyche, Identity and Protest THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Liseli A. Fitzpatrick, B.A. Graduate Program in African American and African Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Lupenga Mphande, Advisor Leslie Alexander Judson Jeffries Copyrighted by Liseli Anne Maria-Teresa Fitzpatrick 2012 Abstract This study on African naming practices during slavery and its aftermath examines the centrality of names and naming in creating, suppressing, retaining and reclaiming African identity and memory. Based on recent scholarly studies, it is clear that several elements of African cultural practices have survived the oppressive onslaught of slavery and European domination. However, most historical inquiries that explore African culture in the Americas have tended to focus largely on retentions that pertain to cultural forms such as religion, dance, dress, music, food, and language leaving out, perhaps, equally important aspects of cultural retentions in the African Diaspora, such as naming practices and their psychological significance. In this study, I investigate African names and naming practices on the African continent, the United States and the Caribbean, not merely as elements of cultural retention, but also as forms of resistance – and their importance to the construction of identity and memory for persons of African descent. As such, this study examines how European colonizers attacked and defiled African names and naming systems to suppress and erase African identity – since names not only aid in the construction of identity, but also concretize a people’s collective memory by recording the circumstances of their experiences. -

NATIONAL ENDOWMENT F0R`~THE ARTS Appl . NO . : 93-000171

NATIONAL CONFIDENTIAL INQUIRY : REQUEST FOR REVISED BUDGET INFORMATION ENDOWMENT F0R`~THE To : Ste i na Date : 1 1 JUN 1993 ARTS Appl . NO . : 93-000171 Your application to the MEDIA ARTS Program's Film/Video Production category was recently reviewed and recommended for funding by the Program advisory panel and the National Council on the Arts and approved by the Endowment's chairman, but at a level lower than you requested . This inquiry is to The Federal agency advise you of the status of your application and to determine if the that supports the visual, literary and project can be undertaken with the reduced level of Endowment support . The performing arts to final grant award is subject to the availability of funds . benefit all Americans Amt . Recommended : $25,000 Earliest Project Start Date : July 1, 1993 Project Description : To support the production of an interactive laserdisc installation on different landscapes Arts in Education Challenge Fr Advancement If the project can still be undertaken at the reduced amount, please refer to the "INSTRUCTIONS & GUIDANCE" below . Please advise us immediately if Dance you will not be able to undertake the project at all . DesignArts INSTRUCTIONS & GUIDANCE : Please complete the attached Revised Budget Expansion Arts form . Only indicate costs which reflect your grant recommendation . The project description should remain substantially the same . If changes in Folk Arts project scope are necessary under the reduced funding, submit a revised project description in the space provided on the Revised Budget form . International Literature If the authorizing official or project director has changed since submission of your application, please send a letter to that effect with Locals your response to this request . -

Personal Name Policy: from Theory to Practice

Dysertacje Wydziału Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu 4 Justyna B. Walkowiak Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu Poznań 2016 Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Dysertacje Wydziału Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu 4 Justyna B. Walkowiak Personal Name Policy: From Theory to Practice Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu Poznań 2016 Projekt okładki: Justyna B. Walkowiak Fotografia na okładce: © http://www.epaveldas.lt Recenzja: dr hab. Witold Maciejewski, prof. Uniwersytetu Humanistycznospołecznego SWPS Copyright by: Justyna B. Walkowiak Wydanie I, Poznań 2016 ISBN 978-83-946017-2-0 *DOI: 10.14746/9788394601720* Wydanie: Wydział Neofilologii UAM w Poznaniu al. Niepodległości 4, 61-874 Poznań e-mail: [email protected] www.wn.amu.edu.pl Table of Contents Preface ............................................................................................................ 9 0. Introduction .............................................................................................. 13 0.1. What this book is about ..................................................................... 13 0.1.1. Policies do not equal law ............................................................ 14 0.1.2. Policies are conscious ................................................................. 16 0.1.3. Policies and society ..................................................................... 17 0.2. Language policy vs. name policy ...................................................... 19 0.2.1. Status planning ........................................................................... -

A Cultural Linguistic Approach to Afro-American Onomastics" (2006)

UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations 1-1-2006 LaKesha and KuShawn: A cultural linguistic approach to Afro- American onomastics Clara J Senif University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/rtds Repository Citation Senif, Clara J, "LaKesha and KuShawn: A cultural linguistic approach to Afro-American onomastics" (2006). UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations. 1978. http://dx.doi.org/10.25669/2qdc-i700 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Retrospective Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAKESHA AND KUSHAWN; A CULTURAL LINGUISTIC APPROACH TO AFRO-AMERICAN ONOMASTICS By Clara J. Senif Associate of Arts Brigham Young University, Provo 1987 Bachelor of Arts Brigham Young University, Provo 1995 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Anthropology Department of Anthropology College of Liberal Arts Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2006 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. UMI Number: 1436791 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. -

ISB Approved Controlled Values V1-0

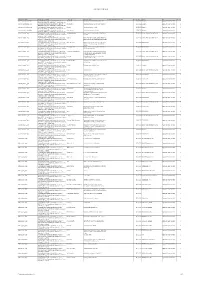

ISB approved controlled values Controlled list Name Contolled list Definition Value Name Value Definition CL Derivation (Aggregations only) Effective Date Source Status Version Absence_Authorisation_Type A controlled list of values that identifies the status of Authorised The absence has been formally requested 25/09/2012 Research Approved: Recommended 2 absence of a PARTY e.g. "Authorised", "Unauthorised", etc. Absence_Authorisation_Type A controlled list of values that identifies the status of Not‐Notified The absence has not been formally requested 25/09/2012 Research Approved: Recommended 2 absence of a PARTY e.g. "Authorised", "Unauthorised", etc. Absence_Authorisation_Type A controlled list of values that identifies the status of Notified The absence was authorised 25/09/2012 Research Approved: Recommended 2 absence of a PARTY e.g. "Authorised", "Unauthorised", etc. Absence_Authorisation_Type A controlled list of values that identifies the status of Unauthorised The absence was not authorised 25/09/2012 Research Approved: Recommended 2 absence of a PARTY e.g. "Authorised", "Unauthorised", etc. Absence_Reason_Type A controlled list of values that identifies the reason as to Attending Interview Expectation that the party will be attending an 23/07/2013 Learner Absentee Reason Type v1 Approved: Recommended 3 why a PARTY is absent during a period when they should be interview present e.g., "Sick", "Holiday", etc. Absence_Reason_Type A controlled list of values that identifies the reason as to Closure Attendance was impossible because attendance 23/07/2013 Learner Absentee Reason Type v1 Approved: Recommended 3 why a PARTY is absent during a period when they should be events were not taking place due to closures etc. -

Moroccan Jewish Onomastics in Casablanca Lessons on Moroccan Jewish Identification and Positionality

Moroccan Jewish Onomastics in Casablanca Lessons on Moroccan Jewish Identification and Positionality Senior Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the School of Arts and Sciences Brandeis University Undergraduate Program in Near Eastern & Judaic Studies Professor Jonathan Decter, Advisor In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Arts By Gabi Hersch May 2017 Copyright by Gabi Hersch Committee Members Name: Professor Jonathan Decter Signature: _____________________________ Name: Professor Bernadette Brooten Signature: _____________________________ Name: Professor ChaeRan Freeze Signature: ______________________________ Hersch 2 Acknowledgements Researching and writing this thesis, from my study abroad semester in Morocco, to my senior year at Brandeis University has been one of the biggest learning experiences of my undergraduate career. I would like to express my sincere appreciation for the guidance of my advisor, Professor Decter. Thank you, firstly, for inspiring me to look into this field through your class “Jews in the World of Islam,” and secondly, for guiding me towards pursuing this particular topic of onomastics, and for showing me where to begin such a study. I never would have thought of this on my own, and I have learned a great deal. Thank you for providing me with beneficial feedback as I made progress on my thesis, and helping me to understand making conclusions within my limitations of study. Another huge thank you to Professor Vanessa Paloma-Elbaz, for all of your incredible help conducting my research during my study abroad semester in Morocco, as well as continuing to help me from across the ocean as I rummaged the internet for archives of names. -

Nationality Classification Using Name Embeddings

Nationality Classification Using Name Embeddings Junting Ye1, Shuchu Han4, Yifan Hu2, Baris Coskun3* , Meizhu Liu2, Hong Qin1, Steven Skiena1 1Stony Brook University, 2Yahoo! Research, 3Amazon AI, 4NEC Labs America fjuyye,shhan,qin,[email protected],fyifanhu,[email protected],[email protected] ABSTRACT Ethnicity Nationality (Lv1) Ritwik Kumar Ravi Kumar Ethnicity Nationality identication unlocks important demographic infor- Muthu Muthukrishnan Mohak Shah Black mation, with many applications in biomedical and sociological Deepak Agarwal White Ying Li research. Existing name-based nationality classiers use name sub- Lei Li API Jianyong Wang AIAN strings as features and are trained on small, unrepresentative sets Yan Liu Shipeng Yu 2PRACE of labeled names, typically extracted from Wikipedia. As a result, HangHang Tong Hispanic Aijun An these methods achieve limited performance and cannot support Qiaozhu Mei Jingrui He ne-grained classication. Xiaoguang Wang Tiger Zhang We exploit the phenomena of homophily in communication pat- Jing Gao Faisal Farooq Nationality (Lv1) terns to learn name embeddings, a new representation that encodes Rayid Ghani Usama Fayyad African gender, ethnicity, and nationality which is readily applicable to Leman Akoglu European Danai Koutra CelticEnglish building classiers and other systems. rough our analysis of 57M Evangelos Simoudis Evangelos Milios Greek Marko Grobelnik Jewish contact lists from a major Internet company, we are able to design a Tijl De Bie Claudia Perlich Muslim ne-grained nationality classier covering 39 groups representing Charles Elkan Nordic Diana Inkpen over 90% of the world population. In an evaluation against other Jennifer Neville EastAsian published systems over 13 common classes, our F1 score (0.795) is Derek Young SouthAsian Andrew Tomkins Hispanic Tina Eliassi-Rad substantial beer than our closest competitor Ethnea (0.580). -

The MCAT® Essentials for Testing Year 2022

The MCAT® Essentials for Testing Year 2022 Required Reading MCAT® is a program of the This guide is required reading and contains important information Association of American Medical Colleges and resources about the examinee agreement, registration instructions, and test-day policies. aamc.org/mcat Prepare for the MCAT® Exam Using AAMC MCAT Official Prep Resources Free Planning and Study Resources Learn about the free AAMC MCAT® Official Prep resources available to help you study for test day. How to Create a Study Plan Khan Academy MCAT Collection Get a six-step guide to help The Khan Academy MCAT Collection you create your own study contains sample content from all four How to Create a Study Plan plan. Use the PDF version or sections of the exam and includes 1,100 for the MCAT® Exam access the online version of videos and 3,000 review questions the guide in the MCAT Official to help you study. The collection was Prep Hub. created by Khan Academy with support and funding from the AAMC and the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. MCAT® is a program of the Association of American Medical Colleges aamc.org/mcat A Road Map to MCAT Critical A Road Map to MCAT® Critical Analysis and Reasoning What’s on the MCAT Exam? Analysis and Reasoning Skills in the Khan Academy MCAT Collection Content Outline Skills in the Khan Academy Read the content lists and MCAT Collection explore what’s tested in the The AAMC mapped the skills Association of four exam sections. American Medical Colleges assessed in the CARS section of the MCAT exam to the free videos, worked examples, and practice passage sets in the Khan Academy MCAT Collection. -

Gramps 3.3 Wiki Manual

From Gramps Gramps 3.3 Wiki Manual Gramps 3.3 Wiki Manual From Gramps Jump to: navigation, search Table of Contents This is the wiki manual for Gramps version 3.3. All users are encouraged to edit this Preface manual to help improve its readability and usability. Why use Gramps? Special copyright notice: All edits to this page need to be under two different Typographical conventions copyright licenses: • GNU Free Documentation License 1.2 - see wiki copyright 1. What's new? • GPL - see manual copyright 2. Getting started These licenses allow the Gramps project to maximally use this wiki manual as 1. Start Gramps free content in future Gramps versions. If you do not agree with this dual li- cense, then do not edit this page. You may only link to other pages within the 2. Choosing a Family Tree wiki which fall only under the GFDL license via external links (using the syn- 3. Tell me how to start right now! tax: [http://www.gramps-project.org/...]), not via internal links. 4. Obtaining Help Also, only use the known conventions 3. Main Window 1. Introduction 2. The different Categories 3. Switching Views and Viewing Modes Previous Index Next 4. Gramplets Category 5. People Category 6. Relationships Category 7. Families Category This page's factual accuracy may be compromised 8. Ancestry Category due to out-of-date information. Please help improve 9. Events Category the Gramps Wiki as a useful resource by updating it. 10. Sources Category 11. Places Category 12. Geography Category Abstract 13. Media Category 14. Repositories Category The Gramps Manual details all aspects of the Gramps software application. -

Continuing Education Board Manual

AMERICAN SPEECH-LANGUAGE-HEARING ASSOCIATION Continuing Education Board Manual Table of Contents Section 1: Introduction .............................................................................................. 6 Purpose and Organization of this Manual ........................................................... 6 Background and History ......................................................................................... 7 ASHA ................................................................................................................................. 7 Vision ................................................................................................................................ 7 Mission ............................................................................................................................. 7 ASHA's Continuing Education Program ..................................................................... 7 Components of ASHA's Continuing Education Program ......................................... 8 Standards Behind ASHA’s Continuing Education Program .................................... 8 Continuing Education Board (CEB) ............................................................................ 9 ASHA National Office Continuing Education Staff ................................................. 10 Section 2: ASHA CE Provider Approval ..................................................................11 Benefits of ASHA Approved CE Provider Status ...............................................11 Applying -

“Living” (Unofficial) Personal Names and Their Research in Slovakia*

“Living” (unofficial) personal names and their research in Slovakia* Iveta Valentová Ľudovít Štúr Institute of Linguistics of the Slovak Academy of Sciences in Bratislava, Slovakia Abstract: The paper deals with the definition of the Slovak onomastic termživé meno (“living name”) and with the origin of this group of anthroponyms. Further, a detailed overview of the development of the theory and methodology of the research into these unofficial personal names is presented. The emphasis is put on the results of the examination of Slovak “living names”, on the ways of their functioning in language communication and on their development tendencies. Last but not least, further possibilities of their study along with causes impeding their research are outlined. Keywords: anthroponomastics, official personal names, living (unofficial) personal names. The definition of the Slovak onomastic term živé meno (“living name”) A living name is in general an unofficial (non-official, unconventional) personal name designating an individual, individuals, or the whole family in colloquial speech, where it fulfils functions of an official name. Living names are, for example,living per- sonal names (unofficial names of persons),living family names (unofficial names of fami- lies), living house names (unofficial names of houses, homesteads and, at the same time, its residents as well)1 and living inhabitant names (inhabitants’ nicknames). Living, unofficial names are anthroponyms used in unofficial or semi-official communication. Vincent Blanár systematically elaborated the theory of official and unofficial names and the methodology of their research in Slovak onomastics (Blanár and Matejčík 1978; Blanár 19962, 20083, 2001c). His theory is based on the contentual and func- tional understanding of a proper name, on the binary character of proper names and the integrity of the linguistic and onomastic status of a proper name.