Changing Name Changing: Framing Rules and the Future of Marital Names Elizabeth E Emenst

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Brookings Africa Research Fellows Application

Foreign Policy Pre-Doctoral Research Fellowship Program Application How to Apply: Interested candidates should submit the following: • Application questionnaire and research project proposal; • One publication or writing sample of 10 pages or less (excerpts of larger works acceptable) in PDF format; • Official or unofficial transcript from graduate institution (course names, professor names, grades received) in PDF format; and • One email message containing all required application attachments is highly preferred, with “PreDoc Application – [Last Name, First Name]” in the subject line. • In addition, three confidential letters of recommendation must be submitted to Brookings directly by referees. Instructions are included at the bottom of this document. Application Deadlines: • Applicants must submit a complete application package to [email protected] no later than January 31, 2016 in order to be considered as a candidate. • Letters of reference must be submitted to [email protected] no later than February 15, 2016. Please Note: • Materials sent through regular postal service will not be accepted. • Incomplete applications and those received after the deadline will not be considered. - continued - 1 Personal Information Full Legal Name (as it appears on your passport):____________________________________________________ Preferred name (or nickname):______________________________________________________ Current position/title: _________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ -

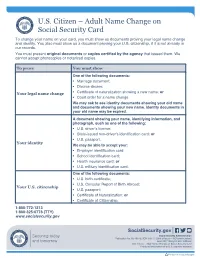

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

Standardization of Parent Company Names - Style Guide

Standardization of Parent Company Names - Style Guide Reporters are required to enter the "Legal Name of United States Parent Company." EPA has defined U.S. parent company(s) as the highest- level U.S. company(s) with an ownership interest in the reporting entity as of December 31 of the year for which data are being reported. Please select you facility's parent company from the pick-list provided. A screen snap of the parent company page is shown below: >> Click this link to expand To improve the quality and utility of GHG data EPA has established guidelines for standardizing corporate parent names. As a first step EPA has established a pick list of existing corporate parents. The following 4 steps were taken standardize the names of on the pick list including: 1) Names were standardized and research was conducted to verify the name submitted was the highest-level of the company in the U. S. 2) For GHG reporters who also report to the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), standardized names were sourced from the TRI parent company database. 3) For the sectors covered by the GHG reporting program only, parent companies were derived from internet research. 4) The List of Parent Companies with local government agencies (e. g., city, town, county government) was removed. A list of the parent company names provided on this pick list is available here. If your facility's parent company is not already on the parent company pick-list you will need to enter the parent company's name in e-GGRT. The following provides a "style guide" for parent company naming: Remember to: Eliminate all periods Enter & instead of AND Use "North America" instead of NA When reporting the Parent Company, use the terms displayed in the "Acronym" column of the table below: Acronym Definition CORP Corporation ASSOC Association CO Company DIV Division INC Incorp/Incorp./Incorporated LP Limited Partnership LTD Limited LLC Limited Liability Company PTNR Partnership USA United States of America US United States. -

We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes Over Children's Surnames Merle H

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 75 | Number 5 Article 3 6-1-1997 We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes over Children's Surnames Merle H. Weiner Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Merle H. Weiner, We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes over Children's Surnames, 75 N.C. L. Rev. 1625 (1997). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol75/iss5/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "WE ARE FAMILY"*: VALUING ASSOCIATIONALISM IN DISPUTES OVER CHILDREN'S SURNAMES MERLE H. WEINER** An increasingvolume of litigation has arisen between divorced or separated parents concerning the surnames of their minor children. For example, a newly divorced mother will sometimes petition the court to change her child's surnamefrom the surname of the absent father to the mother's birth surname or her remarried surname. Courts adjudicating such petitions usually apply one of three standards: a presumption favoring the status quo, a "best interest of the child" test, or a custodial parent presumption. In this Article, Professor Merle Weiner argues that all three of these standards are flawed-either in their express requirements or in their application by the courts-because they reflect men's conception of surnames and undervalue associationalistprinciples. After setting forth her feminist methodology, Professor Weiner explores the differences between men's and women's experiences with their own surnames. -

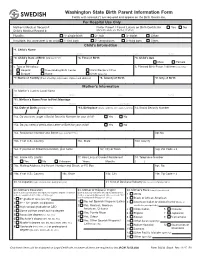

Washington State Birth Filing Form

Washington State Birth Parent Information Form Fields with asterisk (*) are required and appear on the Birth Certificate. For Hospital Use Only Mother’s Medical Record #: Prefer Parent / Parent Labels on Birth Certificate Yes No Child’s Medical Record #: (Default Labels are Mother / Father) Plurality: 1- single birth 2- twin 3- triplet Other: If multiple, this worksheet is for child: 1- first born 2- second born 3- third born Other: Child’s Information *1. Child’s Name First Middle Last Suffix *2. Child’s Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *3. Time of Birth *4. Child’s Sex Male Female 5. Type of Birthplace 6. Planned Birth Place, if different (specify): Hospital Freestanding Birth Center Clinic/Doctor’s Office (specify) Enroute Home Other : Child’s Information Child’s *7. Name of Facility (If not a facility, enter name of place and address) *8. County of Birth *9. City of Birth Mother’s Information 10. Mother’s Current Legal Name First Middle Last Suffix *11. Mother’s Name Prior to First Marriage First Middle Last/Maiden *12. Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *13. Birthplace (State, Territory, or Foreign Country) 14. Social Security Number 15a. Do you want to get a Social Security Number for your child? Yes No 15b. Do you need a Verification Letter of Birth for your child? Yes No 16a. Residence: Number and Street (e.g., 624 SE 5th St.) Apt No. 16b. If not U.S.; Country 16c. State 16d. County 16e. If you live on Tribal Reservation, give name 16f. City or Town 16g. Zip Code + 4 16h. -

Sourceone Search User Guide CONTENTS

SourceOne Search Version 7.2 SP9 User Guide REV 01 February 2020 Copyright © 2005-2020 Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries All rights reserved. Dell believes the information in this publication is accurate as of its publication date. The information is subject to change without notice. THE INFORMATION IN THIS PUBLICATION IS PROVIDED “AS-IS.” DELL MAKES NO REPRESENTATIONS OR WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND WITH RESPECT TO THE INFORMATION IN THIS PUBLICATION, AND SPECIFICALLY DISCLAIMS IMPLIED WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE. USE, COPYING, AND DISTRIBUTION OF ANY DELL SOFTWARE DESCRIBED IN THIS PUBLICATION REQUIRES AN APPLICABLE SOFTWARE LICENSE. Dell Technologies, Dell, EMC, Dell EMC and other trademarks are trademarks of Dell Inc. or its subsidiaries. Other trademarks may be the property of their respective owners. Published in the USA. Dell EMC Hopkinton, Massachusetts 01748-9103 1-508-435-1000 In North America 1-866-464-7381 www.DellEMC.com 2 SourceOne Search User Guide CONTENTS Preface 7 Chapter 1 Getting Started 11 Accessing Dell EMC SourceOne Search............................................................ 12 Logging in to Dell EMC SourceOne Search........................................................12 About logging in and user authentication.............................................. 12 Specifying a domain..............................................................................12 UPN Support........................................................................................ 13 Limitations and considerations..............................................................13 -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

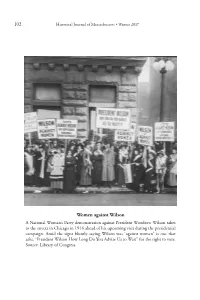

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

African Names and Naming Practices: the Impact Slavery and European

African Names and Naming Practices: The Impact Slavery and European Domination had on the African Psyche, Identity and Protest THESIS Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Liseli A. Fitzpatrick, B.A. Graduate Program in African American and African Studies The Ohio State University 2012 Thesis Committee: Lupenga Mphande, Advisor Leslie Alexander Judson Jeffries Copyrighted by Liseli Anne Maria-Teresa Fitzpatrick 2012 Abstract This study on African naming practices during slavery and its aftermath examines the centrality of names and naming in creating, suppressing, retaining and reclaiming African identity and memory. Based on recent scholarly studies, it is clear that several elements of African cultural practices have survived the oppressive onslaught of slavery and European domination. However, most historical inquiries that explore African culture in the Americas have tended to focus largely on retentions that pertain to cultural forms such as religion, dance, dress, music, food, and language leaving out, perhaps, equally important aspects of cultural retentions in the African Diaspora, such as naming practices and their psychological significance. In this study, I investigate African names and naming practices on the African continent, the United States and the Caribbean, not merely as elements of cultural retention, but also as forms of resistance – and their importance to the construction of identity and memory for persons of African descent. As such, this study examines how European colonizers attacked and defiled African names and naming systems to suppress and erase African identity – since names not only aid in the construction of identity, but also concretize a people’s collective memory by recording the circumstances of their experiences.