Child Protection and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

International Naming Conventions NAFSA TX State Mtg

1 2 3 4 1. Transcription is a more phonetic interpretation, while transliteration represents the letters exactly 2. Why transcription instead of transliteration? • Some English vowel sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some English consonant sounds don’t exist in the other language and vice‐versa • Some languages are not written with letters 3. What issues are related to transcription and transliteration? • Lack of consistent rules from some languages or varying sets of rules • Country variation in choice of rules • Country/regional variations in pronunciation • Same name may be transcribed differently even within the same family • More confusing when common or religious names cross over several countries with different scripts (i.e., Mohammad et al) 5 Dark green countries represent those countries where Arabic is the official language. Lighter green represents those countries in which Arabic is either one of several official languages or is a language of everyday usage. Middle East and Central Asia: • Kurdish and Turkmen in Iraq • Farsi (Persian) and Baluchi in Iran • Dari, Pashto and Uzbek in Afghanistan • Uyghur, Kazakh and Kyrgyz in northwest China South Asia: • Urdu, Punjabi, Sindhi, Kashmiri, and Baluchi in Pakistan • Urdu and Kashmiri in India Southeast Asia: • Malay in Burma • Used for religious purposes in Malaysia, Indonesia, southern Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines Africa: • Bedawi or Beja in Sudan • Hausa in Nigeria • Tamazight and other Berber languages 6 The name Mohamed is an excellent example. The name is literally written as M‐H‐M‐D. However, vowels and pronunciation depend on the region. D and T are interchangeable depending on the region, and the middle “M” is sometimes repeated when transcribed. -

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

Reference Guides for Registering Students with Non English Names

Getting It Right Reference Guides for Registering Students With Non-English Names Jason Greenberg Motamedi, Ph.D. Zafreen Jaffery, Ed.D. Allyson Hagen Education Northwest June 2016 U.S. Department of Education John B. King Jr., Secretary Institute of Education Sciences Ruth Neild, Deputy Director for Policy and Research Delegated Duties of the Director National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance Joy Lesnick, Acting Commissioner Amy Johnson, Action Editor OK-Choon Park, Project Officer REL 2016-158 The National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance (NCEE) conducts unbiased large-scale evaluations of education programs and practices supported by federal funds; provides research-based technical assistance to educators and policymakers; and supports the synthesis and the widespread dissemination of the results of research and evaluation throughout the United States. JUNE 2016 This project has been funded at least in part with federal funds from the U.S. Department of Education under contract number ED‐IES‐12‐C‐0003. The content of this publication does not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the U.S. Department of Education nor does mention of trade names, commercial products, or organizations imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. REL Northwest, operated by Education Northwest, partners with practitioners and policymakers to strengthen data and research use. As one of 10 federally funded regional educational laboratories, we conduct research studies, provide training and technical assistance, and disseminate information. Our work focuses on regional challenges such as turning around low-performing schools, improving college and career readiness, and promoting equitable and excellent outcomes for all students. -

Brookings Africa Research Fellows Application

Foreign Policy Pre-Doctoral Research Fellowship Program Application How to Apply: Interested candidates should submit the following: • Application questionnaire and research project proposal; • One publication or writing sample of 10 pages or less (excerpts of larger works acceptable) in PDF format; • Official or unofficial transcript from graduate institution (course names, professor names, grades received) in PDF format; and • One email message containing all required application attachments is highly preferred, with “PreDoc Application – [Last Name, First Name]” in the subject line. • In addition, three confidential letters of recommendation must be submitted to Brookings directly by referees. Instructions are included at the bottom of this document. Application Deadlines: • Applicants must submit a complete application package to [email protected] no later than January 31, 2016 in order to be considered as a candidate. • Letters of reference must be submitted to [email protected] no later than February 15, 2016. Please Note: • Materials sent through regular postal service will not be accepted. • Incomplete applications and those received after the deadline will not be considered. - continued - 1 Personal Information Full Legal Name (as it appears on your passport):____________________________________________________ Preferred name (or nickname):______________________________________________________ Current position/title: _________________________________________________________________________ __________________________________________________________________________________________ -

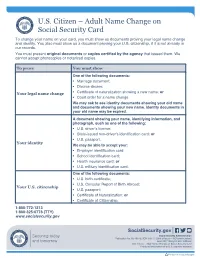

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

The Qanon Conspiracy

THE QANON CONSPIRACY: Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy THE QANON CONSPIRACY: PRESENTED BY Destroying Families, Dividing Communities, Undermining Democracy NETWORK CONTAGION RESEARCH INSTITUTE POLARIZATION AND EXTREMISM RESEARCH POWERED BY (NCRI) INNOVATION LAB (PERIL) Alex Goldenberg Brian Hughes Lead Intelligence Analyst, The Network Contagion Research Institute Caleb Cain Congressman Denver Riggleman Meili Criezis Jason Baumgartner Kesa White The Network Contagion Research Institute Cynthia Miller-Idriss Lea Marchl Alexander Reid-Ross Joel Finkelstein Director, The Network Contagion Research Institute Senior Research Fellow, Miller Center for Community Protection and Resilience, Rutgers University SPECIAL THANKS TO THE PERIL QANON ADVISORY BOARD Jaclyn Fox Sarah Hightower Douglas Rushkoff Linda Schegel THE QANON CONSPIRACY ● A CONTAGION AND IDEOLOGY REPORT FOREWORD “A lie doesn’t become truth, wrong doesn’t become right, and evil doesn’t become good just because it’s accepted by the majority.” –Booker T. Washington As a GOP Congressman, I have been uniquely positioned to experience a tumultuous two years on Capitol Hill. I voted to end the longest government shut down in history, was on the floor during impeachment, read the Mueller Report, governed during the COVID-19 pandemic, officiated a same-sex wedding (first sitting GOP congressman to do so), and eventually became the only Republican Congressman to speak out on the floor against the encroaching and insidious digital virus of conspiracy theories related to QAnon. Certainly, I can list the various theories that nest under the QAnon banner. Democrats participate in a deep state cabal as Satan worshiping pedophiles and harvesting adrenochrome from children. President-Elect Joe Biden ordered the killing of Seal Team 6. -

Contag 100 011

UB-INNSBRUCK FAKULTATSBIBLIOTHEK THEOLOGIE Z3 CONTAG 100 011 VOLUME 11 SPRING 2004 EDITOR ANDREW MCKENNA I LOYOLA UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO ADVISORY EDITORS REN£ GIRARD, STANFORD UNIVERSITY JAMES WILLIAMS, SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY EDITORIAL BOARD REBECCA ADAMS CHERYL K3RK-DUGGAN UNIVERSITY OF NOTRE DAME MEREDITH COLLEGE MARK ANSPACH PAISLEY LIVINGSTON £COLE POLYTECHNIQUE, PARIS MCGILL UNIVERSITY CESAREO BANDERA CHARLES MABEE UNIVERSITY OF NORTH CAROLINA ECUMENICAL THEOLOGICAL SEMINARY, DETROIT DIANA CULBERTSON KENT STATE UNIVERSITY JOZEF NIEWIADOMSKI THEOLOGISCHE HOCHSCHULE, LINZ JEAN-PIERRE DUPUY STANFORD UNIVERSITY, £COLE POLYTECHNIQUE SUSAN NOWAK SYRACUSE UNIVERSITY PAUL DUMOUCHEL UNIVERSITE DU QUEBEC A MONTREAL WOLFGANG PALAVER UNIVERSITAT INNSBRUCK ERIC GANS UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, LOS ANGELES MARTHA REINEKE UNIVERSITY OF NORTHERN IOWA SANDOR GOODHART WHITMAN COLLEGE TOBIN SIEBERS UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN ROBERT HAMERTON-KELLY STANFORD UNIVERSITY THEE SMITH EMORY UNIVERSITY HANS JENSEN AARHUS UNIVERSITY, DENMARK MARK WALLACE SWARTHMORE COLLEGE MARK JUERGENSMEYER UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, EUGENE WEBB SANTA BARBARA UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON Rates for the annual issue of Contagion are: individuals $10.00; institutions $32. The editors invite submission of manuscripts dealing with the theory or practical application of the mimetic model in anthropology, economics, literature, philosophy, psychology, religion, sociology, and cultural studies. Essays should conform to the conventions of The Chicago Manual of Style and should not exceed a length of 7,500 words including notes and bibliography. Accepted manuscripts will require final sub- mission on disk written with an IBM compatible program. Please address correspondence to Andrew McKenna, Department of Modern Languages and Literatures, Loyola University, Chicago, IL 60626. Tel: 773-508-2850; Fax: 773-508-2893; Email: [email protected]. Member of the Council of Editors of Learned Journals CELJ © 1996 Colloquium on Violence and Religion at Stanford ISSN 1075-7201 Cover illustration: Pieter Bruegel the Elder, Envy, 1557. -

Standardization of Parent Company Names - Style Guide

Standardization of Parent Company Names - Style Guide Reporters are required to enter the "Legal Name of United States Parent Company." EPA has defined U.S. parent company(s) as the highest- level U.S. company(s) with an ownership interest in the reporting entity as of December 31 of the year for which data are being reported. Please select you facility's parent company from the pick-list provided. A screen snap of the parent company page is shown below: >> Click this link to expand To improve the quality and utility of GHG data EPA has established guidelines for standardizing corporate parent names. As a first step EPA has established a pick list of existing corporate parents. The following 4 steps were taken standardize the names of on the pick list including: 1) Names were standardized and research was conducted to verify the name submitted was the highest-level of the company in the U. S. 2) For GHG reporters who also report to the Toxics Release Inventory (TRI), standardized names were sourced from the TRI parent company database. 3) For the sectors covered by the GHG reporting program only, parent companies were derived from internet research. 4) The List of Parent Companies with local government agencies (e. g., city, town, county government) was removed. A list of the parent company names provided on this pick list is available here. If your facility's parent company is not already on the parent company pick-list you will need to enter the parent company's name in e-GGRT. The following provides a "style guide" for parent company naming: Remember to: Eliminate all periods Enter & instead of AND Use "North America" instead of NA When reporting the Parent Company, use the terms displayed in the "Acronym" column of the table below: Acronym Definition CORP Corporation ASSOC Association CO Company DIV Division INC Incorp/Incorp./Incorporated LP Limited Partnership LTD Limited LLC Limited Liability Company PTNR Partnership USA United States of America US United States. -

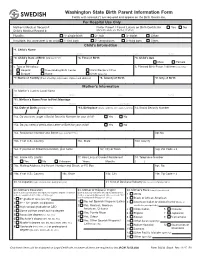

Washington State Birth Filing Form

Washington State Birth Parent Information Form Fields with asterisk (*) are required and appear on the Birth Certificate. For Hospital Use Only Mother’s Medical Record #: Prefer Parent / Parent Labels on Birth Certificate Yes No Child’s Medical Record #: (Default Labels are Mother / Father) Plurality: 1- single birth 2- twin 3- triplet Other: If multiple, this worksheet is for child: 1- first born 2- second born 3- third born Other: Child’s Information *1. Child’s Name First Middle Last Suffix *2. Child’s Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *3. Time of Birth *4. Child’s Sex Male Female 5. Type of Birthplace 6. Planned Birth Place, if different (specify): Hospital Freestanding Birth Center Clinic/Doctor’s Office (specify) Enroute Home Other : Child’s Information Child’s *7. Name of Facility (If not a facility, enter name of place and address) *8. County of Birth *9. City of Birth Mother’s Information 10. Mother’s Current Legal Name First Middle Last Suffix *11. Mother’s Name Prior to First Marriage First Middle Last/Maiden *12. Date of Birth (MM/DD/YYYY) *13. Birthplace (State, Territory, or Foreign Country) 14. Social Security Number 15a. Do you want to get a Social Security Number for your child? Yes No 15b. Do you need a Verification Letter of Birth for your child? Yes No 16a. Residence: Number and Street (e.g., 624 SE 5th St.) Apt No. 16b. If not U.S.; Country 16c. State 16d. County 16e. If you live on Tribal Reservation, give name 16f. City or Town 16g. Zip Code + 4 16h. -

GLOBAL BURDEN of ARMED VIOLENCE 2011 ISBN 978-1-107-60679-1 Takes an Integrated an Takes 2011

he Global Burden of Armed Violence 2011 takes an integrated approach to the complex and volatile dynamics of armed GENEVA T violence around the world. Drawing on comprehensive country- DECLARATION level data, including both conflict-related and criminal violence, it estimates that at least 526,000 people die violently every year, more than three-quarters of them in non-conflict settings. It highlights that the 58 countries with high rates of lethal violence account for two- thirds of all violent deaths, and shows that one-quarter of all violent GLOBAL deaths occur in just 14 countries, seven of which are in the Americas. New research on femicide also reveals that about 66,000 women GLOBAL BURDEN VIOLENCE and girls are violently killed around the world each year. 2 0 1 1 1 1 1 1 This volume also assesses the linkages between violent death rates and socio-economic development, demonstrating that homicide rates are higher wherever income disparity, extreme poverty, and hunger are high. It challenges the use of simple analytical classifications and policy responses, and offers researchers and policy-makers new tools for studying and tackling different forms of violence. of ARMED VIOLENCE o f ARMED BURDEN Photos Top left: Rescuers evacuate a wounded person from Utoeya, Norway, July 2011. © Morten Edvarsen/AFP Photo Lethal Centre left: Morgue workers transport a coffin to be buried along with other unidentified bodies found in mass graves, Durango, Mexico, June 2011. © Jorge Valenzuela/Reuters Encounters Bottom right: An armed fighter walks past a burnt-out armed vehicle in the Abobo 2011 district of Abidjan, Côte d’Ivoire, March 2010. -

![Infanticide [Dictionary Entry] M](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8197/infanticide-dictionary-entry-m-1078197.webp)

Infanticide [Dictionary Entry] M

Marquette University e-Publications@Marquette Theology Faculty Research and Publications Theology, Department of 11-1-2011 Infanticide [Dictionary Entry] M. Therese Lysaught Marquette University Published version. "Infanticide [Dictionary Entry]," in Dictionary of Scripture and Ethics. Eds. Joel B. Green, Jacqueline E. Lapsley, Rebekah Miles, and Allen Verhey. Grand Rapids, Mich: Baker Publishing Group, 2011. Publisher Link. Used with permission. © 2011 Baker Publishing Group. No print copies may be produced without obtaining written permission from Baker Publishing Group. Inequality See Equality Infanticide Infanticide refers to intentional practices that cause the death of newborn infants or, second arily, older children. Scripture and the Christian tradition are un equivocal: infanticide is categorically condemned. Both Judaism and Christianity distinguished themselves in part via their opposition to wide spread practices of infanticide in their cultural contexts. Are Christian communities today like wise distinguished, Of, like many of their Israel ite forebears, do they profess faith in God while worshiping Molech? Infanticide in Scripture Infanticide stands as an almost universal practice across history and culture (Williamson). Primary justifications often cite economic scarcity or popu lation control needs, although occasionally infan ticide flourished in prosperous cultural contexts (Levenson) . Infanticide or, more precisely, child sacrifice forms the background of much of the OT. Jon Levenson argues that the transformation of child sacrifice, captured in the repeated stories of the death and resurrection of the beloved and/or first born son, is at the heart of the Judea-Christian tradition. The Israelites found themselves among peoples who practiced child sacrifice, particularly sacrifice of the firstborn son. In Deut. 12:31 it is said of the inhabitants of Canaan that "they even burn their sons and their daughters in the fire to their gods" (d. -

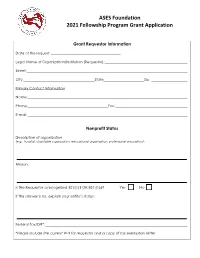

ASES Foundation 2021 Fellowship Program Grant Application

ASES Foundation 2021 Fellowship Program Grant Application Grant Requestor Information Date of the request: Legal Name of Organization/Institution (Requestor): Street: City: State Zip: Primary Contact Information Name: Phone: Fax: E-mail: Nonprofit Status Description of organization (e.g., hospital, charitable organization, educational organization, professional association): Mission: Is the Requestor a recognized 501(c)3 OR 501 (c)6? Yes No If the answer is no, explain your entity’s status: Federal Tax ID#*: *Please include the current W-9 for requestor and a copy of tax exemption letter Payee Information (if different from grant requestor above) Legal Name: Street: City: State Zip: Primary Contact Information Name: Phone: Fax: E-mail: ASES-Recognized Fellowship Program Information Fellowship Program Name: Accreditation status: (check all that apply) ACGME accredited ASES-recognized Program Year fellowship began: Years of participation in the ASES Fellowship Match: Fellowship Director’s Title: Fellowship Director’s Name (Last, First): ASES Member: Yes No Member category: Dedicated Fellowship Program Faculty Members (list first/last name and credentials below): Faculty 1 ASES Member Category Faculty 2 ASES Member Category Faculty 3 ASES Member Category Faculty 4 ASES Member Category Faculty 5 ASES Member Category Total Number of Fellows to Participate in the 2020-2021 Fellowship: Total Number of Fellows that Participated in the 2019-2020 Fellowship: Are all program fellows US/Canada graduates with license to practice in US/Canada? Yes