CEDAW Book Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes Over Children's Surnames Merle H

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 75 | Number 5 Article 3 6-1-1997 We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes over Children's Surnames Merle H. Weiner Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Merle H. Weiner, We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes over Children's Surnames, 75 N.C. L. Rev. 1625 (1997). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol75/iss5/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "WE ARE FAMILY"*: VALUING ASSOCIATIONALISM IN DISPUTES OVER CHILDREN'S SURNAMES MERLE H. WEINER** An increasingvolume of litigation has arisen between divorced or separated parents concerning the surnames of their minor children. For example, a newly divorced mother will sometimes petition the court to change her child's surnamefrom the surname of the absent father to the mother's birth surname or her remarried surname. Courts adjudicating such petitions usually apply one of three standards: a presumption favoring the status quo, a "best interest of the child" test, or a custodial parent presumption. In this Article, Professor Merle Weiner argues that all three of these standards are flawed-either in their express requirements or in their application by the courts-because they reflect men's conception of surnames and undervalue associationalistprinciples. After setting forth her feminist methodology, Professor Weiner explores the differences between men's and women's experiences with their own surnames. -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

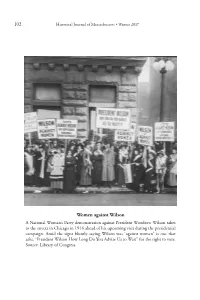

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

Married Women's Names in the United States

Names, Vol. 32, No.2 (June 1984) Manners Make Laws: Married Women's Names in the United States UNA STANNARD The fundamental facts about married women's names and the law are simple. After the eleventh century when surnames began to be used in England, it gradually became the custom for women to change their name to their husband's. They did so as a matter of choice, availing themselves of the right of English people to change their name at will. As Chief Justice Edward Coke said in 1628, though a person may have only one Christian name, "he may have divers surnames ... at divers times," I the Chief Justice himself having a wife who did not use his surname. Even after it became well-nigh universal among English-speaking people for a woman to change her name to her husband's, England continued to recognize that the custom was not' 'compellable by law. It has no statu- tory authority or force. "2 American common law follows English com- mon law in regard to names. Nevertheless, whenever an American wom- an chose not to follow custom, she was almost invariably told by bureaucrats, lawyers, and judges that her name, will-she nill-she, had automatically been changed by her marriage as a matter of law. Not until very recently has the American legal profession been able to face the facts of English common law. I: LUCY STONE The legal difficulties of Lucy Stone, probably the first nineteenth- century American woman to keep her own name after marriage,3 were a forecast of the way the American legal profession was to handle the problem in the twentieth century. -

Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 30 Open Source and Proprietary Models of Innovation January 2009 All Names Are Not Equal: Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection Kelly Snyder Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kelly Snyder, All Names Are Not Equal: Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection, 30 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 561 (2009), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol30/iss1/17 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All Names Are Not Equal: Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection Kelly Snyder INTRODUCTION What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other word would smell as sweet. —William Shakespeare1 With all respect to Mr. Shakespeare, names matter. One‘s name is closely associated with self-identity, and serves the practical function of identification by friends, family, businesses, and the government. People generally are closely tied to their names, shown in part by the great consideration many parents give in naming their children. Names are often changed to reflect different life events or statuses— such as a marrying woman adopting the last name of her new husband. For a long time, marriage has signaled a joining of two (or more) people for the foreseeable future. -

Open Klaskowski.Pdf

The Pennsylvania State University The Graduate School College of the Liberal Arts WOMEN’S POST MARITAL NAME RETENTION AND THE COMMUNICATION OF IDENTITY A Thesis in Communication Arts and Sciences by Kara A. Laskowski © 2006 Kara A. Laskowski Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy August 2006 The thesis of Kara A. Laskowski was reviewed and approved* by the following: Ronald L. Jackson II Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Thesis Adviser Chair of Committee Dennis Gouran Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences and Labor Studies and Industrial Relations Lisa S. Hogan Senior Lecturer in Communication Arts and Sciences and Women's Studies Michelle Miller-Day Associate Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Stephanie Shields Professor of Psychology and Women’s Studies James Dillard Professor of Communication Arts and Sciences Head of the Department of Communication Arts and Sciences *Signatures are on file in the Graduate School. iii ABSTRACT A growing body of research in the field of communication has focused on identity, and has paralleled studies in psychology, family studies, and gender studies on the significance of women’s naming practices after marriage. However, despite the fact that nearly ten percent of married women choose to retain their name in one form or another, and the widely recognized significance of using the correct form of address, no study has attempted to describe how post-marital name retention works to communicate women’s identity. This dissertation was motivated by a desire to provide an account of women’s post-marital name retention and the communication of identity that is both theoretically grounded and representational of the native voices of women who have kept their names after marriage. -

Making a Name: Women's Surnames at Marriage and Beyond

Journal of Economic Perspectives—Volume 18, Number 2—Spring 2004—Pages 143–160 Making a Name: Women’s Surnames at Marriage and Beyond Claudia Goldin and Maria Shim hroughout U.S. history, few women have deviated from the custom of taking their husband’s name (Stannard, 1977). The earliest known in- T stance of a U.S. woman who retained her surname upon marriage is Lucy Stone, the tireless antislavery and female suffrage crusader, who married in 1855. In the 1920s, a generation after her death in 1893, prominent feminists formed the Lucy Stone League to help married women preserve the identity of their own surnames. But until the late 1970s, almost all women, even the highly educated and eminent, assumed their husband’s surname upon marriage. When prominent women who married before the 1970s wished to keep their maiden names as part of their professional image, they sometimes used their maiden names as their middle names, like the U.S. Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Sandra Day O’Connor. Ordinary observation suggests that during the past 25 to 30 years, the fraction of college graduate women retaining their surnames has greatly increased. But the basic facts concerning women’s surnames as a social indicator have eluded inves- tigation because none of the usual data sets contains the current married and maiden surnames of women. This article seeks to estimate the fraction of women who are “keepers” and the factors that have prompted women to retain their surnames. We use three complementary sources—New York Times wedding announce- ments, Harvard alumni records and Massachusetts birth records—to examine patterns of surname retention. -

Marital Naming/Naming Marriage: Language and Status in Family Law

Indiana Law Journal Volume 85 Issue 3 Article 4 Summer 2010 Marital Naming/Naming Marriage: Language and Status in Family Law Suzanne A. Kim Rutgers School of Law-Newark, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj Part of the Family Law Commons Recommended Citation Kim, Suzanne A. (2010) "Marital Naming/Naming Marriage: Language and Status in Family Law," Indiana Law Journal: Vol. 85 : Iss. 3 , Article 4. Available at: https://www.repository.law.indiana.edu/ilj/vol85/iss3/4 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School Journals at Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Indiana Law Journal by an authorized editor of Digital Repository @ Maurer Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marital Naming/Naming Marriage: Language and Status in Family Law SuzANNE A. KIM* INTRODUCTION ....................................................................................................... 894 I. D EFINING STATUS ............................................................................................... 896 II. D EFINING LANGUAGE ........................................................................................ 898 III. N AM ING M ARRIAGE ......................................................................................... 902 A. THE LANGUAGE OF SAME-SEX MARRIAGE ............................................... 902 B. THE PUBLIC NATURE OF NAMING MARRIAGE ......................................... -

Marital Naming/Naming Marriage: Language and Status in Family Law

Marital Naming/Naming Marriage: Language and Status in Family Law SUZANNE A. KIM INTRODUCTION....................................................................................................... 894 I. DEFINING STATUS ............................................................................................... 896 II. DEFINING LANGUAGE ........................................................................................ 898 III. NAMING MARRIAGE ......................................................................................... 902 A. THE LANGUAGE OF SAME-SEX MARRIAGE ............................................... 902 B. THE PUBLIC NATURE OF NAMING MARRIAGE .......................................... 904 C. NAMING MARRIAGE AS GENDERED .......................................................... 906 IV. MARITAL NAMING ............................................................................................ 910 A. MOVING FROM PUBLIC TO PRIVATE .......................................................... 910 B. THE PRIVATE CHOICE OF MARITAL NAMING ............................................ 922 C. MARITAL NAMING AS GENDERED ............................................................. 932 V. REDEFINING MARRIAGE THROUGH NAMING ...................................................... 939 CONCLUSION .......................................................................................................... 941 HISTORICAL APPENDIX ON FEMINISM AND NAMES ................................................. 944 A. NAMES AND FEMINISM’S FIRST -

A Spouse by Any Other Name

William & Mary Journal of Race, Gender, and Social Justice Volume 17 (2010-2011) Issue 1 William & Mary Journal of Women and Article 6 the Law November 2010 A Spouse by Any Other Name Deborah J. Anthony Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl Part of the Family Law Commons Repository Citation Deborah J. Anthony, A Spouse by Any Other Name, 17 Wm. & Mary J. Women & L. 187 (2010), https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl/vol17/iss1/6 Copyright c 2010 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/wmjowl A SPOUSE BY ANY OTHER NAME DEBORAH J. ANTHONY* ABSTRACT This article will investigate current state laws regarding the change of a husband’s name to his wife’s upon marriage. Given that tradition, and often law itself, discourage that practice, the lingering gendered norms that perpetuate the historical tradition will be ex- plored. Components of this article will include a brief historical analysis of the origin of surnames and the law as it has developed on that issue, including an examination of the place of tradition in the law both empirically and normatively. A discussion of the psycho- logical importance of names in the identities of men versus women will be addressed, as will possible justifications for the distinction between the rights of men and women in this regard. Finally, this article will discuss the application of gender discrimination laws and constitutional equal protection doctrine to current laws that provide differing rights and privileges based solely on one’s status as a wife versus a husband. -

![Blackwell Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered 2005-01-18.125127.86]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2170/blackwell-family-papers-finding-aid-library-of-congress-pdf-rendered-2005-01-18-125127-86-6682170.webp)

Blackwell Family Papers [Finding Aid]. Library of Congress. [PDF Rendered 2005-01-18.125127.86]

The Blackwell Family A Register of Its Papers in the Library of Congress Prepared by Grover Batts and Thelma Queen Revised by Nazera S. Wright and Margaret McAleer Manuscript Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 1997 Contact information: http://lcweb.loc.gov/rr/mss/address.html Text converted and initial EAD tagging provided by Apex Data Services, 1999 January; encoding completed by Manuscript Division, 1999 2004-11-24 converted from EAD 1.0 to EAD 2002 Collection Summary Title: Blackwell Family Papers Span Dates: 1759-1960 Bulk Dates: (bulk 1845-1890) ID No.: MSS12880 Creator: Blackwell family Extent: 29,000 items; 96 containers; 40 linear feet; 76 microfilm reels Language: Collection material in English Repository: Manuscript Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. Abstract: Family members include author and suffragist Alice Stone Blackwell (1857-1950); her parents, Henry Browne Blackwell (1825-1909) and Lucy Stone (1818-1893), abolitionists and advocates of women's rights; her aunt, Elizabeth Blackwell (1821-1910), the first woman to receive an academic medical degree; and Elizabeth Blackwell's adopted daughter, Kitty Barry Blackwell (1848-1936). Includes correspondence, diaries, articles, and speeches of these and other Blackwell family members. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the Library's online catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically therein. Names: Algeo, Sara MacCormack, 1876-1953--Correspondence Anthony, Susan B. (Susan Brownell), 1820-1906--Correspondence Beecher, Henry Ward, 1813-1887--Correspondence Blackwell family Breshko-Breshkovskaia, Ekaterina Konstantinovna, 1844-1934--Correspondence Byron, Anne Isabella Milbanke Byron, Baroness, 1792-1860--Correspondence Catt, Carrie Chapman, 1859-1947--Correspondence Flores Magón, Ricardo, 1873-1922--Correspondence Funk, Antoinette, d. -

Gender Issues in Selected Short Stories by Dorothy Parker

"I'M A FEMINIST": GENDER ISSUES IN SELECTED SHORT STORIES BY DOROTHY PARKER by Lynne Hahn A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of The Schmidt College of Arts and Humanities in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, Florida December 1992 "I'M A FEMINIST" : GENDER ISSUES IN SELECTED SHORT STORIES BY DOROTHY PARKER by Lynne Hahn This thesis was prepared under the direction of the candidate's thesis advisor, Dr. Faith Berry, Department of English and Comparative Literature and has been approved by the members of her supervisory committee. It was submitted to the faculty of The Schmidt College of Arts and Humanities and was accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. S~~y COMMITTEE: Thesis Advb Chairpe son, Department of English ~~ ~ Cf 'lLN. IC:, 1 z... Dean of Graduate Studies Date ii ABSTRACT Author: Lynne Hahn Title: "I'm a Feminist": Gender Issues in Selected Short Stories by Dorothy Parker Institution: Florida Atlantic University Thesis Advisor: Dr. Faith Berry Degree: Master of Arts Year: 1992 Dorothy Parker made her "I'm a feminist" claim in a 1956 Paris Review interview with Marion Capron. This thesis proposes that Parker showed an acute awareness of women's issues. As a working woman who demanded equal pay f or equal work, she was aware of gender influenced inequalities. Parker examined the cultural institutions that subordinated women by gender, class and race through her realist fiction. She anticipated the political feminist critique as we know it today.