Making a Name: Women's Surnames at Marriage and Beyond

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identity Theft Literature Review

The author(s) shown below used Federal funds provided by the U.S. Department of Justice and prepared the following final report: Document Title: Identity Theft Literature Review Author(s): Graeme R. Newman, Megan M. McNally Document No.: 210459 Date Received: July 2005 Award Number: 2005-TO-008 This report has not been published by the U.S. Department of Justice. To provide better customer service, NCJRS has made this Federally- funded grant final report available electronically in addition to traditional paper copies. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. This document is a research report submitted to the U.S. Department of Justice. This report has not been published by the Department. Opinions or points of view expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the official position or policies of the U.S. Department of Justice. IDENTITY THEFT LITERATURE REVIEW Prepared for presentation and discussion at the National Institute of Justice Focus Group Meeting to develop a research agenda to identify the most effective avenues of research that will impact on prevention, harm reduction and enforcement January 27-28, 2005 Graeme R. Newman School of Criminal Justice, University at Albany Megan M. McNally School of Criminal Justice, Rutgers University, Newark This project was supported by Contract #2005-TO-008 awarded by the National Institute of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, U.S. Department of Justice. Points of view in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the official position or policies of the U.S. -

Dod Enterpriseidentity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM)

UNCLASSIFIED DoD Enterprise Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) Reference Design Version 1.0 June 2020 Prepared by Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT C. Distribution authorized to U.S. Government agencies and their contractors (Administrative or Operational Use). Other requests for this document shall be referred to the DCIO-CS. UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Document Approvals Prepared By: N. Thomas Lam IE/Architecture and Engineering Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) Thomas J Clancy, COL US Army CS/Architecture and Capability Oversight, DoD ICAM Lead Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) Approved By: Peter T. Ranks Deputy Chief Information Officer for Information Enterprise (DCIO IE) Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) John (Jack) W. Wilmer III Deputy Chief Information Officer for Cyber Security (DCIO CS) Department of Defense, Office of the Chief Information Officer (DoD CIO) ii UNCLASSIFIED UNCLASSIFIED Version History Version Date Approved By Summary of Changes 1.0 TBD TBD Renames and replaces the IdAM Portfolio Description dated August 2015 and the IdAM Reference Architecture dated April 2014. (Existing IdAM SDs and TADs will remain valid until updated versions are established.) Updates name from Identity and Access Management (IdAM) to Identity, Credential, and Access Management (ICAM) to align with Federal government terminology Removes and cancels -

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

PERSONAL and SOCIAL IDENTITY: SELF and SOCIAL CONTEXT John C. Turner, Penelope J. Oakes, S. Alexander Haslam and Craig Mcgarty D

PERSONAL AND SOCIAL IDENTITY: SELF AND SOCIAL CONTEXT John C. Turner, Penelope J. Oakes, S. Alexander Haslam and Craig McGarty Department of Psychology Australian National University Paper presented to the Conference on "The Self and the Collective" Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ, 7-10 May 1992 A revised version of this paper will appear in Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin Special Issue on The Self and the Collective Professor J. C. Turner Department of Psychology GPO Box 4, ANU Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia Tel: 06 249 3094 Fax: 06 249 0499 Email: [email protected] 30 April 1992 2 Abstract Social identity and self-categorization theories provide a distinctive perspective on the relationship between the self and the collective. They assume that individuals can and do act as both individual persons and social groups and that, since both individuals and social groups exist objectively, both personal and social categorical self-categorizations provide valid representations of self in differing social contexts. As social psychological theories of collective behaviour, they take for granted that they cannot provide a complete explanation of the concrete social realities of collective life. They define their task as providing an analysis of the psychological processes that interact with and make possible the distinctive "group facts" of social life. From the early 1970s, beginning with Tajfel's research on social categorization and intergroup discrimination, social identity theory has explored the links between the self- evaluative aspects of social'identity and intergroup conflict. Self-categorization theory, emerging from social identity research in the late 1970s, made a basic distinction between personal and social identity as differing levels of inclusiveness in self-categorization and sought to show how the emergent, higher-order properties of group processes could be explained in terms of a functional shift in self-perception from personal to social identity. -

Name Change Checklist

Name Change Checklist Government Agencies Social Security Administration Department of Motor Vehicles - driver's license, car title and registration Voter Registration US Passport Post Office, if change of address Military or Veteran Records Public Assistance Naturalization Papers Any open court orders Work and Employment W-4 Form 401k Health Insurance Benefits (including Beneficiaries) Email ID Card Business Cards Name Plate Work website / website contact information Unions Professional Organizations Professional Licenses Personal website – if you have a resume based website Banks / Financial Institutions Checking accounts, checks, and bank cards Savings and money market accounts, CDs Credit Cards Assets such as property titles, deeds, trusts Debts such as mortgages and personal loans Debts such as auto or school loans Investment accounts, including IRAs, and 401ks Insurance Policies such as life, disability Home Homeowners or renters insurance Landlord Home owners association or management agency Property Tax department / Tax assessor Utilities o Electric o Gas o Water / sewer o Telephones (including cell and landline) o Internet o Cable Auto Insurance Medical Doctor Dentist Ob-Gyn Therapists Counselors Eye Doctor Pharmacy Veterinarian / Micro Chip Company Personal School / School Records / Alumni Associations Groups, Associations, Organizations Subscriptions Airline Miles Programs Loyalty Clubs Road Toll Accounts Your Voicemail Gym Membership Church / Religious Organizations Other Legal Documents Health proxy Power of Attorney Will Living Trusts Your Attorney Social Media Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Flickr Instagram Personal Blog or Website Email Accounts Brought to you by http://www.littlethingsfavors.com . -

Constructed Identity, Subjective Identity and Inter-Subjective Transformation: an Exploration by Way of Motherhood and Canadian Maternity Benefits

Wilfrid Laurier University Scholars Commons @ Laurier Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) 2009 Constructed Identity, Subjective Identity and Inter-Subjective Transformation: An Exploration By Way of Motherhood and Canadian Maternity Benefits Patricia Van Katwyk Wilfrid Laurier University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd Part of the Social Work Commons Recommended Citation Van Katwyk, Patricia, "Constructed Identity, Subjective Identity and Inter-Subjective Transformation: An Exploration By Way of Motherhood and Canadian Maternity Benefits" (2009). Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive). 1081. https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/1081 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Commons @ Laurier. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations (Comprehensive) by an authorized administrator of Scholars Commons @ Laurier. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre r&ference ISBN: 978-0-494-54261-3 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-54261-3 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'internet, prefer, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. -

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents Of

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents of Greater Capital Region, New York By, Lettie Dickerson, Esq., Milo Primeaux, Esq., Kevin M. Nelson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................................ 3 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1: CHANGING YOUR NAME IN COURT ............................................................................ 6 STEP BY STEP OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 6 PREPARING THE PETITION ............................................................................................................................ 8 ABOUT NAME CHANGE PUBLICATION REQUIREMENT ................................................................................... 9 NAME CHANGE APPLICATION CHECKLIST ...................................................................................................10 SECTION 2: UPDATING ID .....................................................................................................................11 SOCIAL SECURITY .......................................................................................................................................11 -

PRELIMINARY STAFF REPORT To: City Planning Commission Prepared By: Nicolette Jones, Stosh Kozlowski, Laura Baños, and Derreck Deason Date: February 16, 2015

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Consideration: Request by City Council Motion M-15-444 for the City Planning Commission to conduct a study and public hearing to amend its Administrative Rules, Policies, & Procedures relative to the creation of an honorary street name change process. Background: To date, the City of New Orleans does not have a policy related to an honorary street dedication program. Currently, the City’s street naming policy, which is documented in the City Planning Commission’s Administrative Rules, Policies, and Procedures, only delineates the procedure for street name changes. An honorary street dedication program, which many other jurisdictions across the country have implemented, allows cities the opportunity to commemorate individuals and groups who have made significant contributions to the community, but without causing any disruption of the existing street grid associated with a modification to the Official Map as would a permanent street name change. According to best practices, honorary street signage is typically a secondary sign that is installed above or below an existing street name sign. The City Council has granted honorary street dedications in the recent past, though without a formalized policy to guide the process. Following the recent approval of street name changes in the spring of 2015, the New Orleans City Council requested that the City Planning Commission review the City’s street renaming rules and explore opportunities to create an honorary street dedication program. Recommendation: In order to promote clear wayfinding, efficient emergency response and service delivery, as well as accurate address keeping, the staff advises against frequent changes to the City’s Official Map. -

Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services

The University of the State of New York The State Education Department Office of the Professions Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services www.op.nysed.gov DO NOT USE THIS FORM IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY. IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY, YOU MUST SUBMIT A CONTACT US FORM ON THE OFFICE OF THE PROFESSIONS' WEBSITE AT https://eservices.nysed.gov/professions/contact-us/#/ Instructions: Use this form to report a change in your name. Read these instructions carefully and complete all applicable sections of this form. Be sure to print clearly in ink. You must include acceptable supporting documentation. Acceptable supporting documentation includes: A photocopy of a court, marriage certificate, or divorce papers authorizing your name change and a photocopy of a photo ID in your new name. Or Two (2) of the following sets of supporting documents: ● A letter from the Social Security Administration indicating both your old and new names. ● Copies of both old and new driver's licenses. ● Copies of both old and new New York State non-driver photo ID cards. ● Copies of both old and new Social Security Cards. ● Copies of both old and new passports. ● Copies of both old and new U.S. Military photo ID cards. Other forms of identification may be acceptable as supporting documentation. Please contact the Records and Archives Unit by calling 518-474-3817 Extension 380 or by emailing [email protected] before submitting. Currently registered licensed professionals will be sent a new registration certificate. Also, if you would like to replace your existing license parchment with one in your new name, check the appropriate box in Section II and enclose your original parchment (your original parchment will be letter sized, 8.5 x 11 inches, and will not have your address on it). -

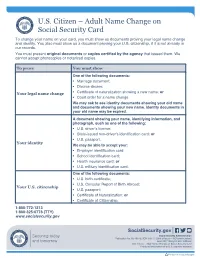

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

Names and “Doing Gender”: How Forenames and Surnames

Sex Roles DOI 10.1007/s11199-017-0805-4 FEMINIST FORUM REVIEW ARTICLE Names and BDoing Gender^: How Forenames and Surnames Contribute to Gender Identities, Difference, and Inequalities Jane Pilcher1 # The Author(s) 2017. This article is an open access publication Abstract Names, as proper nouns, are clearly important for Nonetheless, practices of personal naming in these countries the identification of individuals in everyday life. In the present are patterned and structured: first, as a consequence of repli- article, I argue that forenames and surnames need also to be cation of usage of the names of individuals and recurring recognized as Bdoing^ words, important in the categorization demands for the authentication of individual identity over of sex at birth and in the ongoing management of gender time; second, by cultural traditions and conventions (including conduct appropriate to sex category. Using evidence on per- those patrilineal and patriarchal in origin) whereby personal sonal naming practices in the United States and United names are used to mark individual and social identities (Finch Kingdom, I examine what happens at crisis points of sexed 2008). Despite their fundamental and ubiquitous importance and gendered naming in the life course (for example, at the for each individual in a multitude of contexts, scholars are birth of babies, at marriage, and during gender-identity transi- only just beginning to give personal names and naming prac- tions). I show how forenames and surnames help in the em- tices Bthe theoretical and analytical scrutiny^ they deserve bodied doing of gender and, likewise, that bodies are key to (Palsson 2014,p.618).