Names and “Doing Gender”: How Forenames and Surnames

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Family Law Form 12.982(A), Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (02/18) Copies, and the Clerk Can Tell You the Amount of the Charges

INSTRUCTIONS FOR FLORIDA SUPREME COURT APPROVED FAMILY LAW FORM 12.982(a) PETITION FOR CHANGE OF NAME (ADULT) (02/18) When should this form be used? This form should be used when an adult wants the court to change his or her name. This form is not to be used in connection with a dissolution of marriage or for adoption of child(ren). If you want a change of name because of a dissolution of marriage or adoption of child(ren) that is not yet final, the change of name should be requested as part of that case. This form should be typed or printed in black ink and must be signed before a notary public or deputy clerk. You should file the original with the clerk of the circuit court in the county where you live and keep a copy for your records. What should I do next? Unless you are seeking to restore a former name, you must have fingerprints submitted for a state and national criminal records check. The fingerprints must be taken in a manner approved by the Department of Law Enforcement and must be submitted to the Department for a state and national criminal records check. You may not request a hearing on the petition until the clerk of court has received the results of your criminal history records check. The clerk of court can instruct you on the process for having the fingerprints taken and submitted, including information on law enforcement agencies or service providers authorized to submit fingerprints electronically to the Department of Law Enforcement. -

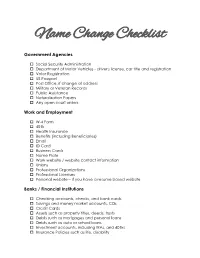

Name Change Checklist

Name Change Checklist Government Agencies Social Security Administration Department of Motor Vehicles - driver's license, car title and registration Voter Registration US Passport Post Office, if change of address Military or Veteran Records Public Assistance Naturalization Papers Any open court orders Work and Employment W-4 Form 401k Health Insurance Benefits (including Beneficiaries) Email ID Card Business Cards Name Plate Work website / website contact information Unions Professional Organizations Professional Licenses Personal website – if you have a resume based website Banks / Financial Institutions Checking accounts, checks, and bank cards Savings and money market accounts, CDs Credit Cards Assets such as property titles, deeds, trusts Debts such as mortgages and personal loans Debts such as auto or school loans Investment accounts, including IRAs, and 401ks Insurance Policies such as life, disability Home Homeowners or renters insurance Landlord Home owners association or management agency Property Tax department / Tax assessor Utilities o Electric o Gas o Water / sewer o Telephones (including cell and landline) o Internet o Cable Auto Insurance Medical Doctor Dentist Ob-Gyn Therapists Counselors Eye Doctor Pharmacy Veterinarian / Micro Chip Company Personal School / School Records / Alumni Associations Groups, Associations, Organizations Subscriptions Airline Miles Programs Loyalty Clubs Road Toll Accounts Your Voicemail Gym Membership Church / Religious Organizations Other Legal Documents Health proxy Power of Attorney Will Living Trusts Your Attorney Social Media Facebook Twitter Pinterest LinkedIn Flickr Instagram Personal Blog or Website Email Accounts Brought to you by http://www.littlethingsfavors.com . -

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents Of

Pro Se Name & Gender Change Guide for Transgender Residents of Greater Capital Region, New York By, Lettie Dickerson, Esq., Milo Primeaux, Esq., Kevin M. Nelson 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 DISCLAIMER ................................................................................................................................................ 3 FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS ................................................................................................................. 4 SECTION 1: CHANGING YOUR NAME IN COURT ............................................................................ 6 STEP BY STEP OVERVIEW ............................................................................................................................. 6 PREPARING THE PETITION ............................................................................................................................ 8 ABOUT NAME CHANGE PUBLICATION REQUIREMENT ................................................................................... 9 NAME CHANGE APPLICATION CHECKLIST ...................................................................................................10 SECTION 2: UPDATING ID .....................................................................................................................11 SOCIAL SECURITY .......................................................................................................................................11 -

PRELIMINARY STAFF REPORT To: City Planning Commission Prepared By: Nicolette Jones, Stosh Kozlowski, Laura Baños, and Derreck Deason Date: February 16, 2015

CITY PLANNING COMMISSION CITY OF NEW ORLEANS MITCHELL J. LANDRIEU ROBERT D. RIVERS MAYOR EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR LESLIE T. ALLEY DEPUTY DIRECTOR City Planning Commission Staff Report Executive Summary Consideration: Request by City Council Motion M-15-444 for the City Planning Commission to conduct a study and public hearing to amend its Administrative Rules, Policies, & Procedures relative to the creation of an honorary street name change process. Background: To date, the City of New Orleans does not have a policy related to an honorary street dedication program. Currently, the City’s street naming policy, which is documented in the City Planning Commission’s Administrative Rules, Policies, and Procedures, only delineates the procedure for street name changes. An honorary street dedication program, which many other jurisdictions across the country have implemented, allows cities the opportunity to commemorate individuals and groups who have made significant contributions to the community, but without causing any disruption of the existing street grid associated with a modification to the Official Map as would a permanent street name change. According to best practices, honorary street signage is typically a secondary sign that is installed above or below an existing street name sign. The City Council has granted honorary street dedications in the recent past, though without a formalized policy to guide the process. Following the recent approval of street name changes in the spring of 2015, the New Orleans City Council requested that the City Planning Commission review the City’s street renaming rules and explore opportunities to create an honorary street dedication program. Recommendation: In order to promote clear wayfinding, efficient emergency response and service delivery, as well as accurate address keeping, the staff advises against frequent changes to the City’s Official Map. -

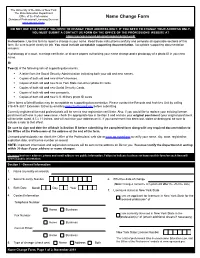

Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services

The University of the State of New York The State Education Department Office of the Professions Name Change Form Division of Professional Licensing Services www.op.nysed.gov DO NOT USE THIS FORM IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY. IF YOU NEED TO CHANGE YOUR ADDRESS ONLY, YOU MUST SUBMIT A CONTACT US FORM ON THE OFFICE OF THE PROFESSIONS' WEBSITE AT https://eservices.nysed.gov/professions/contact-us/#/ Instructions: Use this form to report a change in your name. Read these instructions carefully and complete all applicable sections of this form. Be sure to print clearly in ink. You must include acceptable supporting documentation. Acceptable supporting documentation includes: A photocopy of a court, marriage certificate, or divorce papers authorizing your name change and a photocopy of a photo ID in your new name. Or Two (2) of the following sets of supporting documents: ● A letter from the Social Security Administration indicating both your old and new names. ● Copies of both old and new driver's licenses. ● Copies of both old and new New York State non-driver photo ID cards. ● Copies of both old and new Social Security Cards. ● Copies of both old and new passports. ● Copies of both old and new U.S. Military photo ID cards. Other forms of identification may be acceptable as supporting documentation. Please contact the Records and Archives Unit by calling 518-474-3817 Extension 380 or by emailing [email protected] before submitting. Currently registered licensed professionals will be sent a new registration certificate. Also, if you would like to replace your existing license parchment with one in your new name, check the appropriate box in Section II and enclose your original parchment (your original parchment will be letter sized, 8.5 x 11 inches, and will not have your address on it). -

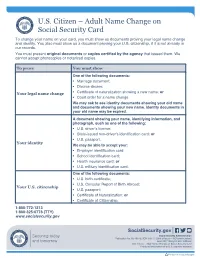

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card to Change Your Name on Your Card, You Must Show Us Documents Proving Your Legal Name Change and Identity

U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card To change your name on your card, you must show us documents proving your legal name change and identity. You also must show us a document proving your U.S. citizenship, if it is not already in our records. You must present original documents or copies certified by the agency that issued them. We cannot accept photocopies or notarized copies. To prove You must show One of the following documents: • Marriage document; • Divorce decree; Your legal name change • Certificate of naturalization showing a new name; or • Court order for a name change. We may ask to see identity documents showing your old name and documents showing your new name. Identity documents in your old name may be expired. A document showing your name, identifying information, and photograph, such as one of the following: • U.S. driver’s license; • State-issued non-driver’s identification card; or • U.S. passport. Your identity We may be able to accept your: • Employer identification card; • School identification card; • Health insurance card; or • U.S. military identification card. One of the following documents: • U.S. birth certificate; • U.S. Consular Report of Birth Abroad; Your U.S. citizenship • U.S. passport; • Certificate of Naturalization; or • Certificate of Citizenship. 1-800-772-1213 1-800-325-0778 (TTY) www.socialsecurity.gov SocialSecurity.gov Social Security Administration Publication No. 05-10513 | ICN 470117 | Unit of Issue — HD (one hundred) June 2017 (Recycle prior editions) U.S. Citizen – Adult Name Change on Social Security Card Produced and published at U.S. -

Name Change Adult

HOW TO CHANGE YOUR NAME (for an Adult) Who can ask the court for a name change? change your name back to your former or To change your name, you MUST: maiden name. Order for Name Change: is used by the judge to o Be at least 18 years old; AND o say your Request for Name Change is granted or Have lived in Illinois for at least 6 months. o denied. You CAN NOT change your name if you have been Other forms you may need depending on the facts in convicted of: your case: A felony and have not been pardoned or you o Motion to Waive Notice & Publication: if you finished your sentence less than 10 years ago; o believe that publication would put you at risk of • Certain Class 4 felony cannabis convictions physical harm or discrimination, use this INSTEAD under the Cannabis Control Act, 720 ILCS 550/4 OF Publication Notice of Court Date for Request for or 550/5 may not be a barrier to changing your Name Change. (See "Special note" below about name. You should speak with a lawyer if you when to file your Motion). If your Motion is granted, have a cannabis conviction to see if you are you do not have to publish notice of your request. eligible to have that conviction vacated and o Order on Motion to Waive Notice & Publication: expunged. is used by the judge to say your Motion to Waive o Identity theft or aggravated identity theft and have Notice and Publication is granted or denied. -

Name Change: How Do I Change a Name?

NAME CHANGE: HOW DO I CHANGE A NAME? Can I change my name? Yes, as long as the purpose is not fraudulent, illegal, or interferes with the rights of others. To formally change a name, ask the court to grant an order. Can I change the name of a child or minor? If your child is under 12 months old and both parents agree to a change of name, the Department of Health can make a name change. You need a court order for older children, which requires the names of both biological parents. This process is easier when you have consent from the child’s parents, guardians, and custodians. Legally changing a child’s name has no effect on obligations such as child support or rights of the child’s parents. What if I don’t have consent from parents, guardians and custodians? The clerk will issue you a summons, which is an official notice of your case. This means you must serve copies of your case documents on the child’s other parent, guardians, or custodians. Watch a video on service of process. Where do I apply to change a name? Go to the circuit court in the county where you live. Do NOT go to the District Court in your jurisdiction. Do I need documents or forms? Complete a Petition for Change of Name (Adult) (CC-DR-60) or Petition for Change of Name (Minor) (CC-DR-062). Attach documents with your current name (birth certificate, driver’s license) and documents that show a name change (marriage certificate). -

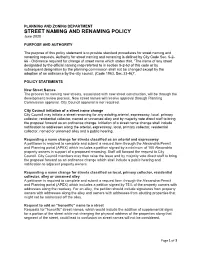

STREET NAMING and RENAMING POLICY June 2020

PLANNING AND ZONING DEPARTMENT STREET NAMING AND RENAMING POLICY June 2020 PURPOSE AND AUTHORITY The purpose of this policy statement is to provide standard procedures for street naming and renaming requests. Authority for street naming and renaming is defined by City Code Sec. 5-2- 66 - Ordinance required for change of street name which states that, "The name of any street designated by the official naming map referred to in section 5-2-63 of this code or by subsequent designation by the planning commission shall not be changed except by the adoption of an ordinance by the city council. (Code 1963, Sec.33-46)". POLICY STATEMENTS New Street Names The process for naming new streets, associated with new street construction, will be through the development review process. New street names will receive approval through Planning Commission approval. City Council approval is nor required. City Council initiation of a street name change City Council may initiate a street renaming for any existing arterial, expressway, local, primary collector, residential collector, named or unnamed alley and by majority vote direct staff to bring the proposal forward as an ordinance change. Initiation of a street name change shall include notification to addresses along the arterial, expressway, local, primary collector, residential collector, named or unnamed alley and a public hearing. Requesting a name change for streets classified as an arterial and expressway A petitioner is required to complete and submit a request form through the Alexandria Permit and Planning portal (APEX) which includes a petition signed by a minimum of 100 Alexandria property owners in support of a proposed renaming. -

Name Change in Conjunction with an Adoption

CHANGE OF NAME PROCEDURES PLEASE READ BEFORE PROCEEDING This information is the only information court personnel can give you about this procedure. This information is not intended to be legal advice, but a brief explanation of the basic procedure that is required. Probate court personnel cannot give legal advice about your particular situation or complete your forms for you. You are not required to have an attorney; however, the court cannot act as your attorney. If you do not understand these instructions or the process, you will need to obtain other assistance. FEES There is a total of $185.00 due at the time of filing ($175.00 filing fee and a $10.00 court service fee). There are also fees for: o Publication (determined by the newspaper where you will be publishing) o Fee for fingerprinting (determined by the agency taking the fingerprints) o Fee to the Michigan State Police for the processing of the fingerprints through the State and Federal LEIN. The State of Michigan determines this cost. After the hearing you may obtain certified copies of the Order Changing Name for a fee of $12.00 each. WAYS THAT A CHANGE OF NAME MAY OCCUR: 1. Correction of the Birth Certificate. If there is a mistake on the birth certificate, you may consult with the Michigan Department of Public Health, Vital Records Division for the proper procedure to correct the mistake at (517)335-8660 (Monday thru Friday 8:00 am. to 5:00 p.m.) or at www.michigan.gov/mdch 2. Changing Last Name after Paternity is Established. -

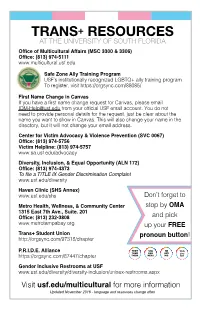

Trans+ Resources

+ TRANSAT THE UNIVERSITY RESOURCES OF SOUTH FLORIDA Office of Multicultural Affairs (MSC 3300 & 3306) Office: (813) 974-5111 www.multicultural.usf.edu Safe Zone Ally Training Program USF’s institutionally recognized LGBTQ+ ally training program To register, visit https://orgsync.com/88085/ First Name Change in Canvas If you have a first name change request for Canvas, please email [email protected] from your official USF email account. You do not need to provide personal details for the request, just be clear about the name you want to show in Canvas. This will also change your name in the directory, but it will not change your email address. Center for Victim Advocacy & Violence Prevention (SVC 0067) Office: (813) 974-5756 Victim Helpline: (813) 974-5757 www.sa.usf.edu/advocacy Diversity, Inclusion, & Equal Opportunity (ALN 172) Office: (813) 974-4373 To file a TITLE IX Gender Discrimination Complaint www.usf.edu/diversity Haven Clinic (SHS Annex) www.usf.edu/shs Don’t forget to Metro Health, Wellness, & Community Center stop by OMA 1315 East 7th Ave., Suite. 201 Office: (813) 232-3808 and pick www.metrotampabay.org up your FREE Trans+ Student Union ! http://orgsync.com/97318/chapter pronoun button THEY SHE HE HE P.R.I.D.E. Alliance THEM HER HIM WriteHIM your https://orgsync.com/87447/chapter THEIR HERS HIS own!HIS Gender Inclusive Restrooms at USF www.usf.edu/diversity/diversity-inclusion/unisex-restrooms.aspx Visit usf.edu/multicultural for more information Updated November 2016 - language and resources change often + This is an introductoryTRANS -

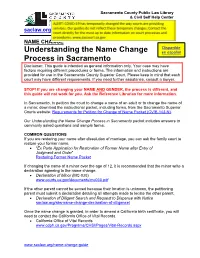

Understanding the Name Change Process in Sacramento Packet Includes Answers to Commonly Asked Questions and Sample Forms

Sacramento County Public Law Library & Civil Self Help Center 609 9th St. Sacramento, CA 95814 saclaw.org (916) 874-6012 NAME CHANGE Disponible Understanding the Name Change en español Process in Sacramento Disclaimer: This guide is intended as general information only. Your case may have factors requiring different procedures or forms. The information and instructions are provided for use in the Sacramento County Superior Court. Please keep in mind that each court may have different requirements. If you need further assistance, consult a lawyer. STOP! If you are changing your NAME AND GENDER, the process is different, and this guide will not work for you. Ask the Reference Librarian for more information. In Sacramento, to petition the court to change a name of an adult or to change the name of a minor; download the instructional packet, including forms, from the Sacramento Superior Courts website: Requirements for Petition for Change of Name Packet (CV/E-142-N). Our Understanding the Name Change Process in Sacramento packet includes answers to commonly asked questions and sample forms. COMMON QUESTIONS If you are restoring your name after dissolution of marriage, you can ask the family court to restore your former name. “Ex Parte Application for Restoration of Former Name after Entry of Judgment and Order” Restoring Former Name Packet If changing the name of a minor over the age of 12, it is recommended that the minor write a declaration agreeing to the name change. Declaration of Minor (MC-030) www.courts.ca.gov/documents/mc030.pdf If the other parent cannot be served because their location is unknown, the petitioning parent must submit a declaration detailing all attempts made to locate the other parent.