Gender Issues in Selected Short Stories by Dorothy Parker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American

The Woman-Slave Analogy: Rhetorical Foundations in American Culture, 1830-1900 Ana Lucette Stevenson BComm (dist.), BA (HonsI) A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2014 School of History, Philosophy, Religion and Classics I Abstract During the 1830s, Sarah Grimké, the abolitionist and women’s rights reformer from South Carolina, stated: “It was when my soul was deeply moved at the wrongs of the slave that I first perceived distinctly the subject condition of women.” This rhetorical comparison between women and slaves – the woman-slave analogy – emerged in Europe during the seventeenth century, but gained peculiar significance in the United States during the nineteenth century. This rhetoric was inspired by the Revolutionary Era language of liberty versus tyranny, and discourses of slavery gained prominence in the reform culture that was dominated by the American antislavery movement and shared among the sisterhood of reforms. The woman-slave analogy functioned on the idea that the position of women was no better – nor any freer – than slaves. It was used to critique the exclusion of women from a national body politic based on the concept that “all men are created equal.” From the 1830s onwards, this analogy came to permeate the rhetorical practices of social reformers, especially those involved in the antislavery, women’s rights, dress reform, suffrage and labour movements. Sarah’s sister, Angelina, asked: “Can you not see that women could do, and would do a hundred times more for the slave if she were not fettered?” My thesis explores manifestations of the woman-slave analogy through the themes of marriage, fashion, politics, labour, and sex. -

A Tempest Or, on the flood of Interest In: Sentiment Analysis, Opinion Mining, and the Computational Treatment of Subjective Language

A Tempest Or, on the flood of interest in: sentiment analysis, opinion mining, and the computational treatment of subjective language Lillian Lee Cornell University http://www.cs.cornell.edu/home/llee “Romance should never begin with sentiment. It should begin with science and end with a settlement.” — Oscar Wilde, An Ideal Husband , that has such people in’t According to a Comscore ’07 report and an ’08 Pew survey: 60% of US residents have done online product research. 15% do so on a typical day. 73%-87% of US readers of online reviews of services say the reviews were significant influences. (more on economics later) But 58% of US internet users report that online information was missing, impossible to find, confusing, and/or overwhelming. Creating technologies that find and analyze reviews would answer a tremendous information need. O brave new world People search for and are affected by online opinions. TripAdvisor, Rotten Tomatoes, Yelp, ... Amazon, eBay, YouTube... blogs, Q&A and discussion sites, ... But 58% of US internet users report that online information was missing, impossible to find, confusing, and/or overwhelming. Creating technologies that find and analyze reviews would answer a tremendous information need. O brave new world, that has such people in’t People search for and are affected by online opinions. TripAdvisor, Rotten Tomatoes, Yelp, ... Amazon, eBay, YouTube... blogs, Q&A and discussion sites, ... According to a Comscore ’07 report and an ’08 Pew survey: 60% of US residents have done online product research. 15% do so on a typical day. 73%-87% of US readers of online reviews of services say the reviews were significant influences. -

We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes Over Children's Surnames Merle H

NORTH CAROLINA LAW REVIEW Volume 75 | Number 5 Article 3 6-1-1997 We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes over Children's Surnames Merle H. Weiner Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Merle H. Weiner, We Are Family: Valuing Associationalism in Disputes over Children's Surnames, 75 N.C. L. Rev. 1625 (1997). Available at: http://scholarship.law.unc.edu/nclr/vol75/iss5/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in North Carolina Law Review by an authorized administrator of Carolina Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "WE ARE FAMILY"*: VALUING ASSOCIATIONALISM IN DISPUTES OVER CHILDREN'S SURNAMES MERLE H. WEINER** An increasingvolume of litigation has arisen between divorced or separated parents concerning the surnames of their minor children. For example, a newly divorced mother will sometimes petition the court to change her child's surnamefrom the surname of the absent father to the mother's birth surname or her remarried surname. Courts adjudicating such petitions usually apply one of three standards: a presumption favoring the status quo, a "best interest of the child" test, or a custodial parent presumption. In this Article, Professor Merle Weiner argues that all three of these standards are flawed-either in their express requirements or in their application by the courts-because they reflect men's conception of surnames and undervalue associationalistprinciples. After setting forth her feminist methodology, Professor Weiner explores the differences between men's and women's experiences with their own surnames. -

'I Want to Go to Jail': the Woman's Party

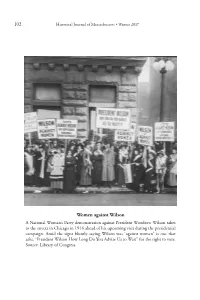

102 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 Women against Wilson A National Woman’s Party demonstration against President Woodrow Wilson takes to the streets in Chicago in 1916 ahead of his upcoming visit during the presidential campaign. Amid the signs bluntly saying Wilson was “against women” is one that asks, “President Wilson How Long Do You Advise Us to Wait” for the right to vote. Source: Library of Congress. 103 “I Want to Go to Jail”: The Woman’s Party Reception for President Wilson in Boston, 1919 JAMES J. KENNEALLY Abstract: Agitation by the National Woman’s Party (NWP) was but one of several factors leading to the successful passage of the Nineteenth Amendment and woman suffrage. By turning to direct action, concentrating on a federal amendment, and courting jail sentences (unlike the more restrained National American Woman Suffrage Association), they obtained maximum publicity for their cause even when, as in Boston, their demonstration had little direct bearing on enfranchisement. Although historians have amply documented the NWP’s vigils and arrests before the White House, the history of the Massachusetts chapter of the NWP and the story of their demonstrations in Boston in 1919 has been mostly overlooked. This article gives these pioneering suffragists their recognition. Nationally, the only women to serve jail sentences on behalf of suffrage were the 168 activists arrested in the District of Columbia and the sixteen women arrested in Boston. Dr. James J. Kenneally, a Professor Emeritus and former Director of Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Vol. 45 (1), Winter 2017 © Institute for Massachusetts Studies, Westfield State University 104 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2017 the Martin Institute at Stonehill College, has written extensively on women’s history.1 * * * * * * * Alice Paul (1885–1977) and Lucy Burns (1879–1966) met in jail in 1909 in England. -

Chicago Writer to Give Visual Presentation on Quincy-Born Algonquin Round Table Member & Artist Neysa Mcmein

Chicago Writer to Give Visual Presentation on Quincy-Born Algonquin Round Table Member & Artist Neysa McMein Chicago writer and poet Cynthia Gallaher will debut her nonfiction book, “Frugal Poets’ Guide to Life: How to Live a Poetic Life, Even If You Aren’t a Poet” at Quincy Art Center, Quincy, Illinois, on Saturday, June 17 at 2 p.m. During this free event, she’ll give a talk and visual presentation on her Quincy-born relative, artist Neysa McMein. Neysa McMein, born in Quincy in 1888, left Quincy after high school to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago before heading east, where she created hundreds of magazine covers, developed the first iconic image of Betty Crocker, and became a member of the famous Algonquin Round Table in New York City, which included writer Dorothy Parker and comic Harpo Marx. McMein’s ancestral relative, Cynthia Gallaher, who holds a degree in art history, helped curate a Neysa McMein art retrospective at Quincy Art Center in 2004 and now returns to the art center to revisit McMein’s work in her PowerPoint visual presentation as well as spotlight McMein’s appearance in “Frugal Poets’ Guide to Life.” "Frugal Poets' Guide to Life" is part memoir, part life-coaching for poets (or those who’d like to live like one) and part creativity guide. “Frugal Poets’ Guide to Life” is a book to nurture any creative person, whether he or she is a #musician, #composer, #dancer, #artist, #fiction, #nonfiction or #drama #writer, or a #poet. This event is part of Frugal Poets' Guide to Life 2017 10-city book tour, partially supported by an Individual Artists Program Grant from the City of Chicago Department of Cultural Affairs & Special Events, as well as a grant from the Illinois Arts Council Agency, a state agency through federal funds provided by the National Endowment for the Arts. -

Married Women's Names in the United States

Names, Vol. 32, No.2 (June 1984) Manners Make Laws: Married Women's Names in the United States UNA STANNARD The fundamental facts about married women's names and the law are simple. After the eleventh century when surnames began to be used in England, it gradually became the custom for women to change their name to their husband's. They did so as a matter of choice, availing themselves of the right of English people to change their name at will. As Chief Justice Edward Coke said in 1628, though a person may have only one Christian name, "he may have divers surnames ... at divers times," I the Chief Justice himself having a wife who did not use his surname. Even after it became well-nigh universal among English-speaking people for a woman to change her name to her husband's, England continued to recognize that the custom was not' 'compellable by law. It has no statu- tory authority or force. "2 American common law follows English com- mon law in regard to names. Nevertheless, whenever an American wom- an chose not to follow custom, she was almost invariably told by bureaucrats, lawyers, and judges that her name, will-she nill-she, had automatically been changed by her marriage as a matter of law. Not until very recently has the American legal profession been able to face the facts of English common law. I: LUCY STONE The legal difficulties of Lucy Stone, probably the first nineteenth- century American woman to keep her own name after marriage,3 were a forecast of the way the American legal profession was to handle the problem in the twentieth century. -

Sponsors of Writing and Workersâ•Ž Education in the 1930S

Community Literacy Journal Volume 11 Issue 1 Fall, Special Issue: Building Engaged Article 3 Infrastructure Fall 2016 Write. Persist. Struggle: Sponsors of Writing and Workers’ Education in the 1930s Deborah Mutnick Dr. Long Island University - Brooklyn Campus, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.fiu.edu/communityliteracy Recommended Citation Mutnick, Deborah. “Write. Persist. Struggle: Sponsors of Writing and Workers’ Education in the 1930s.” Community Literacy Journal, vol. 11, no. 1, 2016, pp. 10–21, doi:10.25148/clj.11.1.009245. This work is brought to you for free and open access by FIU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Community Literacy Journal by an authorized administrator of FIU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. community literacy journal Write. Persist. Struggle: Sponsors of Writing and Workers’ Education in the 1930s Deborah Mutnick Organizations like the John Reed Clubs and the WPA Federal Writers’ Project, as well as publications like The New Masses can be seen as “literacy sponsors” of the U.S. literary left in the 1930s, particularly the young, the working class, and African American writers. The vibrant, inclusionary, activist, literary culture of that era reflected a surge of revolutionary ideas and activity that seized the imagination of a generation of writers and artists, including rhetoricians like Kenneth Burke. Here I argue that this history has relevance for contemporary community writing projects, which collectively lack the political cohesiveness and power of the national and international movements that sponsored the 1930s literary left but may anticipate another global period of struggle for democracy in which writers and artists can play a significant role. -

CPY Document

In The Matter Of: STUART Y SILVERSTEIN v PENGUINPUTMAN, INC. July 17,2007 TRIAL SOUTHERNDISTRICTREPORTERS 500 PEARL STREET NEW YORK., NY 10007 212-805-0300 Original File 77H4SILF.txt, Pages 1-190 Word Index included with this Min-U-Script® STUART Y. SILVERSTEIN v PENGUIN PUTMAN, INC. July 17,2007 Page 1 Page 3 77H7SILI [1] [1] UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT podium? SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK [2] THE COURT: From the podium, please. [2] ------------------------------x [3] MR. RABINOWITZ: Good morning, your Honor. The [3] STUART Y. SILVERSTEIN, [4J evidence will show that after Penguin declined to purchase [4] Plaintiff, [5] Mr. Silverstein's book, and since Mr. Silverstein published it [5J v. 01 Civ. 309 [6] with Scribner, Penguin simply bought a copy, cut and pasted the [6] PENGUIN PUTMAN, INC., [7] pages onto paper, and then republished it as its own book. The [8] evidence will show that such conduct is unheard of in the [7] Defendant. [9] publishing industry. [8] ------------------------------x [10] The evidence will establish that Penguin deliberately [9] July 17, 2007 9:30 a.m. [11] denied Mr. Silverstein attribution in order to "avoid directing [10] [12] people to the competition" and it then misrepresented to the Before: [11] [13] public that the items were faithfully reproduced from their HON. JOHN F. KEENAN [12J [14] original publications. District Judge [15J The evidence will show that senior Penguin employees [13] APPEARANCES [16] violated Penguin's explicit written policies by failing to [14] NEAL GERBER & EISENBERG LLP [17] investigate the copyright status of Silverstein1s work, which [15] Attorneys for Plaintiff BY: MARK A. -

CEDAW Book Final

CEDAW The Treaty for the Rights of Women The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms Discrimination Against Women The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms Discrimination Against Women Rights That Benefit the Entire Community Compiled and Edited by Leila Rassekh Milani, Sarah C. Albert and Karina Purushotma CEDAW The Treaty for the Rights of Women The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms Discrimination Against Women The Convention on the Elimination of All Forms Discrimination Against Women Rights That Benefit the Entire Community Compiled and Edited by Leila Rassekh Milani, Sarah C. Albert and Karina Purushotma The Working Group on Ratification of the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women The Working Group on Ratification of the U.N. Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW) is a group of more than 190 national non-gov- ernmental organizations engaged in outreach and education to achieve ratification by the United States of the U.N. treaty that bans discrimination against women. Co-Chair: Co-Chair: Sarah C. Albert Leila R. Milani Public Policy Director Liaison for Women’s Issues General Federation of Women’s Clubs National Spiritual Assembly 1734 N Street, N.W. of the Bahá’ís of the United States Washington, D.C. 20036 1320 19th Street, N.W., Suite 701 Tel: (202) 347.3168 Washington, D.C. 20036 Fax: (202) 835.0246 Tel: (202) 833.8990 [email protected] Fax: (202) 833.8988 [email protected] © 2004 The Working Group on Ratification of the U.N. -

Dorothy Rothschild Parker

Dorothy Rothschild Parker August 22, 1893 – June 7, 1967 Celebrated Conversationalist renowned for her literary contributions and founder/member of the “Algonquin Round Table” Dorothy Parker Rothschild represented one of the most accomplished feminist and successful literary writers in women’s history. Living from 1893-1967, she became known as one of the most brilliant writers from the early 1900s. Born in West End, New Jersey, and attaining her success from New York, she became one of the most brilliant writers that revolutionized American thinking then and after. Dorothy Parker lived a full and prosperous life, even though she did not have a happy childhood. Growing up, having bad relationships with her father and stepmother, she never had the privilege of growing up with a mother. Her mother died on July 20, 1897, when Dorothy was only four years of age, and her father died shortly after on December 28, 1913. Right before the death of her father was the passing away of her “brother Henry, who died on the passage home from a vacation with his wife Lissie aboard a first class steamship the Titanic, which sank in 1912.” (source link dead) As a sad woman, stung with depression and alcoholism her entire adult life, she had a successful and productive life. In 1916, at the age of 23, she joined the editorial staff of Vogue. Then in 1917 she started working for as a theater critic for Vanity Fair, who had published her first poem entitled “Any Porch,” (1914), in which she received $12. Vanity Fair became a significant variable in her life in that she met her associates whom she would form the Algonquin Round Table/Vicious Circle, an intellectual and renowned literary circle. -

Flappers As Portrayed in Dorothy Parker's Short

The Grove. Working Papers on English Studies 22 (2015): 91-105. DOI: 10.17561/grove.v0i22.2699 FEMALE FIGURES OF THE JAZZ AGE IN DOROTHY PARKER’S SHORT STORIES Isabel López Cirugeda University of Castilla-La Mancha (Spain) Abstract Most criticism on Dorothy Parker (1893–1967) highlights her literary persona only to the detriment of the study of a profuse work comprising six decades of narrative, poetry and drama. Probably her best-known contribution to literature was her condition of the voice of the Jazz Age generation, shifting from acquiescence to irony. A corpus of Parker’s short stories written in the 1920s and early 1930s will be analyzed from feminist perspectives, such as those by Pettit, Melzer or Showalter, in terms of ‘appearance’, ‘social life’ and ‘bonds with men’ to determine whether her heroines respond to the stereotype of the flapper in the Roaring Twenties. Results show a satirized viewpoint conveying dissatisfaction regarding body, idleness and romance predicting many of the conflicts of women in the second half of the XXth century. Keywords: Dorothy Parker, short stories, flappers, Jazz Age, feminist criticism, body, satire. Resumen La mayor parte de los estudios sobre Dorothy Parker (1893–1967) se centran en su condición de personalidad del panorama escénico en detrimento de su profusa obra, con más de seis decenios de narrativa, poesía y teatro. Probablemente su contribución más reconocida sea haber dado voz a la generación de la Era del Jazz, con una visión que oscila entre la complicidad y la ironía. Las heroínas del corpus de relatos escritos por Parker en los años veinte y treinta serán analizadas bajo perspectivas feministas (Pettit, Melzer, Showalter) en términos de ‘apariencia’, ‘vida social’ y ‘relación con los hombres’ para determinar si se acomodan al estereotipo de la flapper. -

Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection

Washington University Journal of Law & Policy Volume 30 Open Source and Proprietary Models of Innovation January 2009 All Names Are Not Equal: Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection Kelly Snyder Washington University School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation Kelly Snyder, All Names Are Not Equal: Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection, 30 WASH. U. J. L. & POL’Y 561 (2009), https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_journal_law_policy/vol30/iss1/17 This Note is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Journal of Law & Policy by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. All Names Are Not Equal: Choice of Marital Surname and Equal Protection Kelly Snyder INTRODUCTION What’s in a name? That which we call a rose By any other word would smell as sweet. —William Shakespeare1 With all respect to Mr. Shakespeare, names matter. One‘s name is closely associated with self-identity, and serves the practical function of identification by friends, family, businesses, and the government. People generally are closely tied to their names, shown in part by the great consideration many parents give in naming their children. Names are often changed to reflect different life events or statuses— such as a marrying woman adopting the last name of her new husband. For a long time, marriage has signaled a joining of two (or more) people for the foreseeable future.