Causes of Daimyo Survn Al in Sixteenth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Real-Life Kantei-Of Swords , Part 10: a Real Challenge : Kantei Wakimono Swords

Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho 1) Introduction Kokan Nakayama in his book “The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords” describes wakimono swords (also called Majiwarimono ) as "swords made by schools that do not belong to the gokaden, as well other that mixed two or three gokaden". His book lists a large number of schools as wakimono, some of these schools more famous than others. Wakimono schools, such as Mihara, Enju, Uda and Fujishima are well known and appear in specialized publications that provide the reader the opportunity to learn about their smiths and the characteristics of their swords. However, others are rarely seen and may be underrated. In this article we will focus on one of the rarely seen and often maligned school from the province of Awa on the Island of Shikoku. The Kaifu School is often associated with Pirates, unique koshirae, kitchen knives and rustic swords. All of these associations are true, but they do not do justice to the school. Kaifu (sometimes said Kaibu) is a relatively new school in the realm of Nihonto. Kaifu smiths started appearing in records during the Oei era (1394). Many with names beginning with UJI or YASU such as Ujiyoshi, Ujiyasu, Ujihisa, Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji , etc, are recorded. However, there is record of the school as far back as Korayku era (1379), where the schools legendary founder Taro Ujiyoshi is said to have worked in Kaifu. There is also a theory that the school was founded around the Oei era as two branches, one following a smith named Fuji from the Kyushu area and other following a smith named Yasuyoshi from the Kyoto area (who is also said to be the son of Taro Ujiyoshi). -

Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogunâ•Žs

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations School of Arts and Sciences October 2012 Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Cecilia S. Seigle Ph.D. University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc Part of the Asian Studies Commons, Economics Commons, Family, Life Course, and Society Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons Recommended Citation Seigle, Cecilia S. Ph.D., "Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1" (2012). Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations. 7. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/ealc/7 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Some Observations on the Weddings of Tokugawa Shogun’s Daughters – Part 1 Abstract In this study I shall discuss the marriage politics of Japan's early ruling families (mainly from the 6th to the 12th centuries) and the adaptation of these practices to new circumstances by the leaders of the following centuries. Marriage politics culminated with the founder of the Edo bakufu, the first shogun Tokugawa Ieyasu (1542-1616). To show how practices continued to change, I shall discuss the weddings given by the fifth shogun sunaT yoshi (1646-1709) and the eighth shogun Yoshimune (1684-1751). The marriages of Tsunayoshi's natural and adopted daughters reveal his motivations for the adoptions and for his choice of the daughters’ husbands. The marriages of Yoshimune's adopted daughters show how his atypical philosophy of rulership resulted in a break with the earlier Tokugawa marriage politics. -

Real-Life Kantei of Swords Part 10

Japanese Swords Society of the United States - Volume 48 No. 4 _______________________________________________________________________________ Real-Life kantei-of swords , part 10: A real challenge : kantei Wakimono Swords W.B. Tanner and F.A.B. Coutinho 1) Introduction Kokan Nakayama in his book “The Connoisseurs Book of Japanese Swords” describes wakimono swords (also called Majiwarimono ) as "swords made by schools that do not belong to the gokaden, as well other that mixed two or three gokaden". His book lists a large number of schools as wakimono, some of these schools more famous than others. Wakimono schools, such as Mihara, Enju, Uda and Fujishima are well known and appear in specialized publications that provide the reader the opportunity to learn about their smiths and the characteristics of their swords. However, others are rarely seen and may be underrated. In this article we will focus on one of the rarely seen and often maligned school from the province of Awa on the Island of Shikoku. The Kaifu School is often associated with Pirates, unique koshirae, kitchen knives and rustic swords. All of these associations are true, but they do not do justice to the school. Kaifu (sometimes said Kaibu) is a relatively new school in the realm of Nihonto. Kaifu smiths started appearing in records during the Oei era (1394). Many with names beginning with UJI or YASU such as Ujiyoshi, Ujiyasu, Ujihisa, Yasuyoshi, Yasuyoshi and Yasuuji , etc, are recorded. However, there is record of the school as far back as Korayku era (1379), where the schools legendary founder Taro Ujiyoshi is said to have worked in Kaifu. -

Iai – Naginata

Editor: Well House, 13 Keere Street, Lewes, East Sussex, England No. 301 Summer 2012 Takami Taizō - A Remarkable Teacher (Part Three) by Roald Knutsen In the last Journal I described something of Takami-sensei’s ‘holiday’ with the old Shintō- ryū Kendō Dōjō down at Charmouth in West Dorset. The first week to ten days of that early June, in perfect weather, we all trained hard in the garden of our house and on both the beach and grassy slopes a few minutes away. The main photo above shows myself, in jōdan-no-kamae against Mick Greenslade, one of our early members, on the cliffs just east of the River Char. The time was 07.30. It is always interesting to train in the open on grass, especially if the ground slopes away! Lower down, we have a pic taken when the tide was out on Lyme Bay. Hakama had to be worn high or they became splashed and sodden very quickly. It is a pity that we haven’t more photos taken of these early practices. The following year, about the same date, four of us were again at Charmouth for a few days and I recall that we had just finished keiko on the sands at 06.30 when an older man, walking his dog, came along – and we were half Copyright © 2012 Eikoku Kendo Renmei Journal of the Eikoku Kendō Renmei No. 301 Summer 2012 a mile west towards the Black Ven (for those who know Charmouth and Lyme) – He paused to look at us then politely asked if we had been there the previous year? We answered in the affirmative, to which he raised his hat, saying: ‘One Sunday morning? I remember you well. -

ASIAN IMAGES· and Now, Back to Earth and Reality, 1981

•• •• • New Year Special Double Issue aCl lC C1 1Zen January 2-9, 1981 The National Publication of the Japanese American Citizens League ISSN: 00JO-!l579 I Whole No. "120 I Vol. 92 NO.1 25c Postpaid - Newsstands l'i~ Nat'l JACL board to meet Feb. 6-8 SAN FRANCISCO-The. National JACL Board meeting announced for Pacific-Asian experts on Jan. .23-25 has been rescheduled to the Feb. 6-8 weekend at National Headquarters, it was announced by J.D. Hokoyama, acting national director, with the first session starting 1 p.m. Friday. aged called to S.F. parley The earl¥ afternoon starting time, it was expIained, would provide SAN FRANCISC~A panel of A<;ian American experts in the necessary nme for board members to appoint a national director as being field of aging, will participate in the national mini-conference recommended by the selection committee. Seven have applied and four are being invited for a final board interview, it was understood. Due to "Pacific-Asians: the Wisdom of Age", Jan 15-16 at the San ~ the financial constraints of the o~tion, candidates are expected to ciscan HoteL to prepare hundred delegates of Asian-Pacific appear at their own expense. However, any applicant who must travel backgrounds for the 1981 White House Conference on Aging. more than once will have their expenses covered. Speakers will include: . • 'I}le ~ition has been vacant since mid-July, when Karl Nobuyuki Dr. Sharon Fujii, regional director, Office of Refugee Resettlement, resigned Just before the JACL Convention. Associate national director Dept of Health and Hwnan Services, San Francisco; Dr. -

Latest Japanese Sword Catalogue

! Antique Japanese Swords For Sale As of December 23, 2012 Tokyo, Japan The following pages contain descriptions of genuine antique Japanese swords currently available for ownership. Each sword can be legally owned and exported outside of Japan. Descriptions and availability are subject to change without notice. Please enquire for additional images and information on swords of interest to [email protected]. We look forward to assisting you. Pablo Kuntz Founder, unique japan Unique Japan, Fine Art Dealer Antiques license issued by Meguro City Tokyo, Japan (No.303291102398) Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Upcoming Sword Shows & Sales Events Full details: http://new.uniquejapan.com/events/ 2013 YOKOSUKA NEX SPRING BAZAAR April 13th & 14th, 2013 kitchen knives for sale YOKOTA YOSC SPRING BAZAAR April 20th & 21st, 2013 Japanese swords & kitchen knives for sale OKINAWA SWORD SHOW V April 27th & 28th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN OKINAWA KAMAKURA “GOLDEN WEEKEND” SWORD SHOW VII May 4th & 5th, 2013 THE MAJOR SWORD SHOW IN KAMAKURA NEW EVENTS ARE BEING ADDED FREQUENTLY. PLEASE CHECK OUR EVENTS PAGE FOR UPDATES. WE LOOK FORWARD TO SERVING YOU. Feel the history.™ uniquejapan.com ! Index of Japanese Swords for Sale # SWORDSMITH & TYPE CM CERTIFICATE ERA / PERIOD PRICE 1 A SADAHIDE GUNTO 68.0 NTHK Kanteisho 12th Showa (1937) ¥510,000 2 A KANETSUGU KATANA 73.0 NTHK Kanteisho Gendaito (~1940) ¥495,000 3 A KOREKAZU KATANA 68.7 Tokubetsu Hozon Shoho (1644~1648) ¥3,200,000 4 A SUKESADA KATANA 63.3 Tokubetsu Kicho x 2 17th Eisho (1520) ¥2,400,000 -

Ore Giapponesi: Giorgio Bernari E Adriano Somigli Lia Beretta

COLLANA DI STUDI GIAPPONESI RICErcHE 4 Direttore Matilde Mastrangelo Sapienza Università di Roma Comitato scientifico Giorgio Amitrano Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Gianluca Coci Università di Torino Silvana De Maio Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale” Chiara Ghidini Fondazione Bruno Kessler Andrea Maurizi Università degli Studi di Milano–Bicocca Maria Teresa Orsi Sapienza Università di Roma Ikuko Sagiyama Università degli Studi di Firenze Virginia Sica Università degli Studi di Milano Comitato di redazione Chiara Ghidini Fondazione Bruno Kessler Luca Milasi Sapienza Università di Roma Stefano Romagnoli Sapienza Università di Rom COLLANA DI STUDI GIAPPONESI RICErcHE La Collana di Studi Giapponesi raccoglie manuali, opere di saggistica e traduzioni con cui diffondere lo studio e la rifles- sione su diversi aspetti della cultura giapponese di ogni epoca. La Collana si articola in quattro Sezioni (Ricerche, Migaku, Il Ponte, Il Canto). I testi presentati all’interno della Collana sono sottoposti a una procedura anonima di referaggio. La Sezione Ricerche raccoglie opere collettanee e monografie di studiosi italiani e stranieri specialisti di ambiti disciplinari che coprono la realtà culturale del Giappone antico, moder- no e contemporaneo. Il rigore scientifico e la fruibilità delle ricerche raccolte nella Sezione rendono i volumi presentati adatti sia per gli specialisti del settore che per un pubblico di lettori più ampio. Variazioni su temi di Fosco Maraini a cura di Andrea Maurizi Bonaventura Ruperti Copyright © MMXIV Aracne editrice int.le S.r.l. www.aracneeditrice.it [email protected] via Quarto Negroni, 15 00040 Ariccia (RM) (06) 93781065 isbn 978-88-548-8008-5 I diritti di traduzione, di memorizzazione elettronica, di riproduzione e di adattamento anche parziale, con qualsiasi mezzo, sono riservati per tutti i Paesi. -

The Goddesses' Shrine Family: the Munakata Through The

THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA by BRENDAN ARKELL MORLEY A THESIS Presented to the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies and the Graduate School ofthe University ofOregon in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master ofArts June 2009 11 "The Goddesses' Shrine Family: The Munakata through the Kamakura Era," a thesis prepared by Brendan Morley in partial fulfillment ofthe requirements for the Master of Arts degree in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies. This thesis has been approved and accepted by: e, Chair ofthe Examining Committee ~_ ..., ,;J,.." \\ e,. (.) I Date Committee in Charge: Andrew Edmund Goble, Chair Ina Asim Jason P. Webb Accepted by: Dean ofthe Graduate School III © 2009 Brendan Arkell Morley IV An Abstract ofthe Thesis of Brendan A. Morley for the degree of Master ofArts in the Interdisciplinary Studies Program: Asian Studies to be taken June 2009 Title: THE GODDESSES' SHRINE FAMILY: THE MUNAKATA THROUGH THE KAMAKURA ERA This thesis presents an historical study ofthe Kyushu shrine family known as the Munakata, beginning in the fourth century and ending with the onset ofJapan's medieval age in the fourteenth century. The tutelary deities ofthe Munakata Shrine are held to be the progeny ofthe Sun Goddess, the most powerful deity in the Shinto pantheon; this fact speaks to the long-standing historical relationship the Munakata enjoyed with Japan's ruling elites. Traditional tropes ofJapanese history have generally cast Kyushu as the periphery ofJapanese civilization, but in light ofrecent scholarship, this view has become untenable. Drawing upon extensive primary source material, this thesis will provide a detailed narrative ofMunakata family history while also building upon current trends in Japanese historiography that locate Kyushu within a broader East Asian cultural matrix and reveal it to be a central locus of cultural production on the Japanese archipelago. -

Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages by Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University)

Vegetables and the Diet of the Edo Period, Part 2 Vegetable Production and the Diet in Rural Villages By Ayako Ehara (Professor Emeritus, Tokyo Kasei-Gakuin University) Introduction compiled by Tomita Iyahiko and completed in 1873, describes the geography and culture of Hida During the Edo period (1603–1868), the number of province. It contains records from 415 villages in villages in Japan remained fairly constant with three Hida counties, including information on land roughly 63,200 villages in 1697 and 63,500 140 years value, number of households, population and prod- later in 1834. According to one source, the land ucts, which give us an idea of the lifestyle of these value of an average 18th and 19th century village, with villagers at the end of the Edo period. The first print- a population of around 400, was as much as 400 to ed edition of Hidago Fudoki was published in 1930 500 koku1, though the scale and character of each vil- (by Yuzankaku, Inc.), and was based primarily on the lage varied with some showing marked individuality. twenty-volume manuscript held by the National In one book, the author raised objections to the gen- Archives of Japan. This edition exhibits some minor eral belief that farmers accounted for nearly eighty discrepancies from the manuscript, but is generally percent of the Japanese population before and during identical. This article refers primarily to the printed the Edo period. Taking this into consideration, a gen- edition, with the manuscript used as supplementary eral or brief discussion of the diet in rural mountain reference. -

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun

Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun 徳川家康 Tokugawa Ieyasu, Shogun Constructed and resided at Hamamatsu Castle for 17 years in order to build up his military prowess into his adulthood. Bronze statue of Tokugawa Ieyasu in his youth 1542 (Tenbun 11) Born in Okazaki, Aichi Prefecture (Until age 1) 1547 (Tenbun 16) Got kidnapped on the way taken to Sunpu as a hostage and sold to Oda Nobuhide. (At age 6) 1549 (Tenbun 18) Hirotada, his father, was assassinated. Taken to Sunpu as a hostage of Imagawa Yoshimoto. (At age 8) 1557 (Koji 3) Marries Lady Tsukiyama and changes his name to Motoyasu. (At age 16) 1559 (Eiroku 2) Returns to Okazaki to pay a visit to the family grave. Nobuyasu, his first son, is born. (At age 18) 1560 (Eiroku 3) Oda Nobunaga defeats Imagawa Yoshimoto in Okehazama. (At age 19) 1563 (Eiroku 6) Engagement of Nobuyasu, Ieyasu’s eldest son, with Tokuhime, the daughter of Nobunaga. Changes his name to Ieyasu. Suppresses rebellious groups of peasants and religious believers who opposed the feudal ruling. (At age 22) 1570 (Genki 1) Moves from Okazaki 天龍村to Hamamatsu and defeats the Asakura clan at the Battle of Anegawa. (At age 29) 152 1571 (Genki 2) Shingen invades Enshu and attacks several castles. (At age 30) 豊根村 川根本町 1572 (Genki 3) Defeated at the Battle of Mikatagahara. (At age 31) 東栄町 152 362 Takeda Shingen’s151 Path to the Totoumi Province Invasion The Raid of the Battlefield Saigagake After the fall of the Imagawa, Totoumi Province 犬居城 武田本隊 (別説) Saigagake Stone Monument 山県昌景隊天竜区 became a battlefield between Ieyasu and Takeda of Yamagata Takeda Main 堀之内の城山Force (another theoried the Kai Province. -

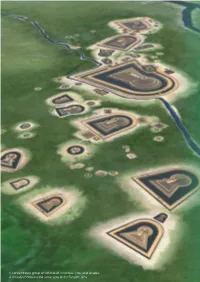

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Types of Japanese Folktales

Types of Japanese Folktales By K e ig o Se k i CONTENTS Preface ............................................................................ 2 Bibliography ................................... ................................ 8 I. Origin of Animals. No. 1-30 .....................................15 II. A nim al Tales. No. 31-74............................................... 24 III. Man and A n im a l............................................................ 45 A. Escape from Ogre. No. 75-88 ....................... 43 B. Stupid Animals. No. 87-118 ........................... 4& C. Grateful Animals. No. 119-132 ..................... 63 IV. Supernatural Wifes and Husbands ............................. 69 A. Supernatural Husbands. No. 133-140 .............. 69 B. Supernatural Wifes. No. 141-150 .................. 74 V. Supernatural Birth. No. 151-165 ............................. 80 VI. Man and Waterspirit. No. 166-170 ......................... 87 VII. Magic Objects. No. 171-182 ......................................... 90 V III. Tales of Fate. No. 183-188 ............................... :.… 95 IX. Human Marriage. No. 189-200 ................................. 100 X. Acquisition of Riches. No. 201-209 ........................ 105 X I. Conflicts ............................................................................I l l A. Parent and Child. No. 210-223 ..................... I l l B. Brothers (or Sisters). No. 224-233 ..............11? C. Neighbors. No. 234-253 .....................................123 X II. The Clever Man. No. 254-262