Pages Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

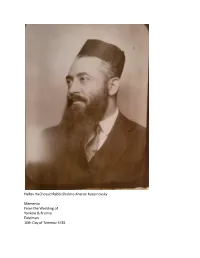

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

UNVERISTY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative In

UNVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 © Copyright by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim by Zachary Alexander Klein Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Richard Dane Danielpour , Co-Chair Professor David Samuel Lefkowitz, Co-Chair In the Chabad-Lubavitch chasidic community, the singing of religious folksongs called nigunim holds a fundamental place in communal and individual life. There is a well-known saying in Chabad circles that while words are the pen of the heart, music is the pen of the soul. The implication of this statement is that music is able to express thoughts and emotions in a deeper way than words could on their own could. In chasidic thought, there are various spiritual narratives that may be expressed through nigunim. These narratives are fundamental in understanding what is being experienced and performed through singing nigunim. At times, the narrative has already been established in Chabad chasidic literature and knowing the particular aspects of this narrative is indispensible in understanding how the nigun unfolds in musical time. ii In other cases, the particular details of this narrative are unknown. In such a case, understanding how melodic construction, mode, ornamentation, and form function to create a musical syntax can inform our understanding of how a nigun can reflect a particular spiritual narrative. This dissertation examines the ways in which musical syntax and spiritual parameters work together to express these various spiritual narratives in sound and structure of nigunim. -

Moshiach Weekly Chof Zayin Adar 5774 a WORD from the EDITORS - Ad Mosai?!

$2.00 . וההוספה בלימוד התורה בעניני משיח והגאולה היא ה"דרך שער הישרה" לפעול התגלות וביאת משיח והגאולה בפועל ממש )משיחת ש"פ תזו"מ ה'תנש"א( The Chossid Who Propagated Moshiach Reb Michoel Teitelbaum I Don't Let My דער רבי זאל זיין געזונט און שטארק! Chassidim Sleep The Story of a Most The World Is Waiting Unforgettable Winter יחי אדוננו מורנו ורבינו מלך המשיח לעולם ועד Index Chof Zayin Adar 5774 - Ad Mosai?! 3 A word from the Editors The Story of a Most Unforgettable Winter דער רבי זאל זיין געזונט און שטארק! 4 Ahavas Yisroel and Moshiach 13 Ksav Yad Kodesh 4 11 I Don't Let My Chassidim Sleep 14 The world is waiting Will they ever come?! 21 A Story רצוננו לראות את מלכנו 24 Ad Mosai Sunday he searches, Monday he searches זונטיג געזוכט, ָמאנטיג געזוכט 26 26 The Chossid Who Propagated Moshiach 32 Reb Michoel Teitelbaum ENOUGH IS ENOUGH! 38 Daloy Golus 24 32 2 | Moshiach Weekly Chof Zayin Adar 5774 A WORD FROM THE EDITORS - Ad Mosai?! It is with great pleasure that we pres- to live with their message and bring ent our readership with this Expanded them down into our daily lives. Edition of Moshiach Weekly, which is In the days leading up to Chof Zayin being released in time for 27 Adar, the Adar, the Rebbe stressed the fact that day when the great helem v'hester be- it's an 'iber yohr' and that there are two gan. months of Adar totaling a 60 day pe- As we approach this moment, and riod of Simcha. -

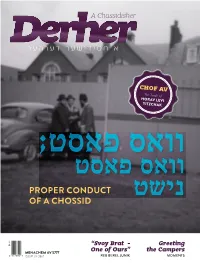

Proper Conduct of a Chossid

CHOF AV The Torah of HORAV LEVI YITZCHAK וואס פאסט; וואס פאסט PROPER CONDUCT נישט OF A CHOSSID $4.99 “Svoy Brat - Greeting MENACHEM AV 5777 One of Ours” the Campers ISSUE 59 (136) REB BEREL JUNIK MOMENTS ב"ה 36 DerherContents MENACHEM AV 5777 ISSUE 59 (136) 54 No Nigleh on Shabbos? Proper conduct of a Chossid 04 DVAR MALCHUS 30 DARKEI HACHASSIDUS “I Felt that my Father In Exchange for a Soldier 06 had Passed On” 34 A CHASSIDISHE MAISE LEBEN MITTEN REBBE’N, CHOF MENACHEM-AV 5704 “Svoy Brat - One of Ours” REB BEREL JUNIK All who are Connected 36 to my Father The Need to Act 11 MOSHIACH KSAV YAD KODESH 49 A Much Needed Transition Days of Meaning A STORY 12 MENACHEM-AV 52 Greeting the Campers Broad Perception and MOMENTS Meticulous Precision 54 14 THE TORAH OF HORAV LEVI YITZCHAK Derher Letters Nonviolent Revolutions 61 28 THE WORLD REVISITED A Chassidisher Derher Magazine is a publication geared toward Bochurim, published and copyrighted by Vaad Talmidei Hatmimim Haolomi. All articles in this publication are original content by the staff of A Chassidisher Derher. Vaad Talmidei Hatmimim Rabbi Moshe Zaklikovsky Photo Credits Rabbi Pinny Lew Rabbi Dovid Junik Rabbi Tzvi Altein Advisory Committee Jewish Educational Media Special Thanks to Rabbi Mordechai Director Rabbi Mendel Alperowitz Library of Agudas Rabbi Chaim Shaul Brook Menashe Laufer Rabbi Yossi Kamman Chassidei Chabad Rabbi Dovid Olidort Rabbi Dovid Dubov Rabbi Shmuel Lubecki Editor in Chief Kehot Publication Society Design Rabbi Mendel Gourarie Rabbi Leibel Posner Rabbi Mendel Jacobs Vaad Hanochos B’Lahak Rabbi Mendy Weg Rabbi Levi Greisman Rabbi Michoel Seligson Editors Junik Family Archives Printed by Rabbi Shamshi Junik Rabbi Elkanah Shmotkin Rabbi Eliezer Zalmanov The Print House Raskin Family Archives Rabbi Menachem Junik Rabbi Shmueli Super Reproduction of any portion of this Magazine is not permissible without express permission from the copyright holders, unless for the use of brief quotations in reviews and similar venues. -

R Zalman Duchman.Indd

ב"ה Family Treasures Memento from the wedding of Efraim and Shaina Duchman 15th of Elul, 5774 • September 10, 2014 Prepared by Dovid Zaklikowski ([email protected]). The Rebbe at the wedding of chosson's grandparents, Mendel and Sara Shemtov, 10 Tamuz, 5716 (June 19th, 1956). In the center (wearing glasses), is his great-grandfather, Reb Zalman Duchman. WELCOME To our dear family and friends, At all joyous events we begin by thanking G-d for granting us life, sustaining us and enabling us to be here together. We are thrilled that you are here to share in our simcha - joyous occasion. Indeed, Jewish law enjoins the entire community to bring joy and elation to the chosson and kallah - the bride and groom. The wedding of the Rebbe, Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, of righteous memory, took place in Warsaw in 1928. In honor of the occasion, the bride’s father, the sixth Chabad Rebbe, distributed a special teshurah, memento, to all the celebrants: a facsimile of a manuscript letter written by the first Chabad Rebbe, Rabbi Schneur Zalman of Liadi. Following this tradition, we are honored to present our memento: a compilation of letters Rabbi Schneur Zalman Duchman, Efraim’s paternal great-grandfather, received from the Rebbe. This is an excerpt from the forthcoming book of stories, translated into English for the first time. This memento is crowned with Mazel Tov wishes from the Rebbe to Shaina's parents and from Rebbetzin Chaya Mushka and Rebbetzin Chana, the Rebbe's mother, to her grandparents, Rabbi Asher and Nechama Heber, may they be blessed with many more happy and healthy years. -

Menachem Av 5781.Pub

בס“ד Menachem Av 5781/2021 S D M A Volume 32, Issue 5 Menachem Av 1/July 10/Shabbos Rosh Chodesh "When Av comes in, we minimize happiness." (Taanis 26B) "In the nine days from Rosh Chodesh Av on, we should try to make Siyumim." (Likutei Sichos Vol. XIV: p. 147) Mountains emerged above the receding flood waters. (BeReishis 8:5, Rashi) Plague of frogs in Mitzrayim. (Seder HaDoros) Yartzeit of Aharon HaKohen, 2489 [1312 BCE], the only Yartzeit recorded in the before the destrucon of the first Beis Hamik- Torah, (BaMidbar 33:38) (in Parshas Masaei, dash). (Yirmiyahu 28) read every year on the Shabbos of the week of his Yartzeit). In the eleventh year of the reign of Tzidkiyahu, on Rosh Chodesh Av, the year of the destruc- Ezra and his followers arrived in on of the Beis Hamikdash, Yechezkel said a Yerushalayim, 3413 [457 BCE]. (Ezra 7:9) prophesy, that the kingdom of Tzur will be de- stroyed by Nevuchadnetzar King of Babylon, In Av 5331 [431 BCE] there was a debate because they celebrated Jerusalem’s destruc- between Chananya ben Azur and Yirmiyahu. on. (Yechezkel 26) Chananya prophesized that Nevuchadnetzer and his armies would soon leave Eretz Yis- Menachem Av 2/July 11/Sunday roel, and all the stolen vessels from the Beis Titus commenced baering operaons against Hamikdash would be returned from Bavel the courtyard of the Beis HaMikdash, 3829 along with all those who were exiled. Yirmi- [70]. yahu explained, that he too wished that this would happen, but the prophesy is false. -

NEWSLETTER Boys Division, Grades B2 - B8 עש“ק פרשת וארא כ“ט טבת Emerging from Our Comfort Zone

ב“ה Issue No. 16 NEWSLETTER Boys division, Grades B2 - B8 עש“ק פרשת וארא כ“ט טבת Emerging From Our Comfort Zone Tayere Talmidei him that after sitting and from what they were Hatmimim sheyichyu, there for a while one used to experiencing. The grows accustomed to the Rebbe explains that this The second Makkoh that situation and they didn’t approach was key to the the Aibershter brought on even notice that it was Yidden leaving Mitzrayim Mitzrayim was the Happy especially dark! When and to breaking Makkoh of Tzefardeiah – Reb Hillel heard this Mitzrayim because it Birthday frogs all over Mitzrayim. conversation he represented the idea of Gabi Yarmush Chazal say that this commented that there is not being comfortable 1 Shevat 5769 Makkoh was particularly an important lesson here: with where you are and important in breaking when a person lives his living in the dark, but Daniel Zaltzman Mitzrayim and leading life in a certain way that rather breaking out of 2 Shevat 5767 the way for the Yidden to really should be changed one’s current level and leave it. not being Mendel Grossbaum satisfied with 2 Shevat 5765 Why was this living in the Makkoh in dark and the Yosef Yitzchok particular cold. This was Meir Bluming singled out for the message 5 Shevat 5763 being extra that Reb Hillel important? was telling the Ari Stolik The Rebbe chassidim. 5 Shevat 5767 explains that Now we can there are many better lessons that we understand could learn why the from the way Makkoh of and improved (it is the frogs acted during Tzefardeah was so “dark”), but he becomes Contact us this time. -

THE MITTELER REBBE: HIS LIFE and 6 LIBERATION 9-10 Kislev| Yitzchok Wagshul

718_Beis Moshiach 16/11/2009 8:45 AM Page 3 contents INWARDNESS: THE PATH TO POSTERITY 4 A LASTING LEGACY D’var Malchus THE MITTELER REBBE: HIS LIFE AND 6 LIBERATION 9-10 Kislev| Yitzchok Wagshul IF LOBSTERS HAD DOCTORS 12 Shlichus | Dr. Aryeh Gotfryd OUR FIVE-YEAR PLAN 16 7 Mitzvos | Hannah Porat HAVE I GOT AN ANSWER FOR YOU! USA 22 Moshiach & Science | Yaacov Moshe Moses 744 Eastern Parkway Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409 Tel: (718) 778-8000 Fax: (718) 778-0800 [email protected] SOULS RETURNING FROM A”Z www.beismoshiach.org 26 Stories | Eli Shneuri EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: M.M. Hendel ENGLISH EDITOR: THE PEOPLE OF THE BOOK Boruch Merkur 32 Shlichus | Rabbi Yaakov Shmuelevitz HEBREW EDITOR: Rabbi Sholom Yaakov Chazan [email protected] THE LELOVER REBBE ZT”L 34 Feature Beis Moshiach (USPS 012-542) ISSN 1082- 0272 is published weekly, except Jewish holidays (only once in April and October) for $160.00 in Crown Heights, Brooklyn and in all other places for $180.00 per year (45 ETERNAL LIFE issues), by Beis Moshiach, 744 Eastern 36 Thought | Rabbi Yosef Karasik Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. Periodicals postage paid at Brooklyn, NY and additional offices. Postmaster: send address changes to Beis Moshiach 744 Eastern Parkway, Brooklyn, NY 11213-3409. ‘MY EMISSARY, THE TORAH’ Copyright 2009 by Beis Moshiach, Inc. 41 Moshiach & Geula | Boruch Merkur Beis Moshiach is not responsible for the content of the advertisements. 718_Beis Moshiach 16/11/2009 8:45 AM Page 4 d’var malchus INWARDNESS: THE PATH TO POSTERITY A LASTING LEGACY Sichos In English world.. -

Feeling Proud (II)

ב"ה למען ישמעו • דברים תשע"ז • 420 EDITOR - RABBI SHIMON HELLINGER FEELING PROUD (II) A Chossid’s Pride fathers, davening slowly from a Siddur. Many were acting in a ‘worldly’ manner, that he was simply envious because their children were different. following the crowd. Today, that has become an Reb Mordechai Lieplier, a prominent chossid of the They would wonder aloud: “How did these come to excuse. When questioned about a behavior, a Alter Rebbe, was firm in his observance of mitzvos, behave like this? These kleine yidelach!” person justifies himself by saying, ‘But everyone thanks to his pride. When his Yetzer HaRa would does it!’ “ When boys were ridiculed for their peyos and tzitzis try to incite him to do something wrong, he would they were not ashamed, nor did they respond, for On another occasion, the Frierdiker Rebbe said: stand up tall and shout, “I?! – the chossid of the they knew the vast difference between them and “Recently, people have begun feeling embarrassed. Alter Rebbe, the wealthy lamdan and maskil (who other children, and looked upon them with pity Embarrassed – from whom? From some ‘clothing on learns Chassidus in depth), should do an aveira?! and sympathy. a post’?! This embarrassment has actually caused That is not befitting for me!” ,many people to compromise their Yiddishkeit )דברי הימים גורקאוו ע' עה( The Rebbe adds that every Yid can have this pride. so that they leave ‘pieces’ at the barbers and the When a Yid thinks of his great ancestors, recalls tailors… We need not be embarrassed by them; they that he stood at Har Sinai and was given the Torah, should be embarrassed by us.” )סה"ש תש"ב ע' and that the entire world was created for him – CONSIDER )126 ,120 ,92 he will feel that it is unbefitting for him to lower himself even in the slightest. -

The WRITTEN TORAH

RITTEN TO the W RAH לקוטי שיחות PART 2 X ELUL 5777 14 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER לזכות החייל בצבאות ה׳ זלמן יודא שיחי׳ שכטר לרגל יום הולדתו, ה׳ אלול נדפס ע״י משפחתו שיחיו IN THE PREVIOUS ARTICLE OF THIS COVERIN TWO-PART SERIES, WE FOCUSED ON DIS G RITTEN TOR THE HISTORICAL SIDE OF LIKKUTEI e W AH SICHOS: WHEN IT BEGAN, HOW IT th WAS PUBLISHED, AND THE REBBE’S INTIMATE INVOLVEMENT. IN THIS ARTICLE, WE ATTEMPT TO TOUCH ON THE CONTENT OF LIKKUTEI SICHOS. There are many sefarim of the Rebbe’s Torah itself—Likkutei Sichos, non-edited sichos, maamarim, igros, reshimos, and so on—and they all share the most critical common denominator: through learning his Torah, we become mekushar with the Rebbe himself in the closest way possible, for the essence of our mind becomes one with him. In this series, we have trained our focus on Likkutei Sichos. JEM 193603 via ELUL 5739, LEVI FREIDIN 5739, ELUL ELUL 5777 A CHASSIDISHER DERHER 15 OUR CAPACITY Likkutei Sichos is an inherently because every sicha includes Reb Shmuel Ber Borisover impossible endeavor. themes in Chassidus; the Rebbe’s (otherwise known as Rashda”m) Furthermore, Likkutei Sichos hashkafa is expressed throughout was one of the most famous is not a single sefer on a single the entire Likkutei Sichos, in all Chassidim of the Tzemach subject; there are so many the different subjects.” Tzedek and Rebbe Maharash. different types of sichos: Rashi “The Alter Rebbe’s sefer is Counted among the greatest sichos, Rambam sichos, Chassidus Tanya,” Rabbi Yosef Gurary maskilim (thinkers in Chassidus) sichos, sichos on the parsha, sichos says. -

Perspectives Issue #5

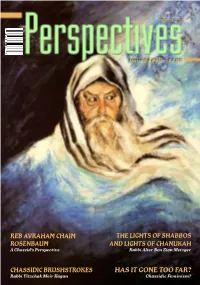

ב"ה | טבת תשע"ד Issue 5 • Price: $4.00 REB AVRAHAM CHAIM THE LIGHTS OF SHABBOS ROSENBAUM AND LIGHTS OF CHANUKAH A Chossid’s Perspective Rabbi Alter Ben Zion Metzger CHASSIDIC BRUSHSTROKES HAS IT GONE TOO Far? Rabbi Yitzchak Meir Kagan Chassidic Feminism? The Best of New York is Right Here. Serving the Community for Over 20 Years ב"ה Events EVERY BEAUTIFUL DETAIL Family EVERY SMILE, EVERY MOMENT Celebrate! BY EVERY EVENT Location CAPTURING EVERY SEASON Weddings CAPTURING EVERY SECOND 917.740.3443 • www.baruchezagui.com View the collection at the SilverSpoon STORE unleash Call to place your order: your 718-467-7770 miles silverspoonstore.com {Corporate accounts our specialty} SELL MILE NOW www.sellmilesnow.com 732.987.7765 +(/3,1*<28%(&20($ RESOLUTIONS %(77(5´<28µ PeacefulUSA :(2))(5$&2035(+(16,9(&2856(72 $//2:8672+(/3<28:,7+<285 %(&20($&(57,),('352)(66,21$/ &2$&+ /,)(·6,668(6 (Yaakov is the only person authorized to teach WGI’s course in the tri-state area. The course is 0DVWHU&HUWLÀHG/LIH&RDFK accredited through the SLA) Learn how to deal with “life’s” issues. How are 2QOLQHDQGRUOLYHLQSHUVRQFODVVHV we different than a therapist? A life Coach’s job is to help you move forward today, regardless 5HFHLYHD1DWLRQDODQG,QWHUQDWLRQDO of your past issues. We focus on the positive. &HUWLÀFDWLRQ &RXUVHLQFOXGHV 6SHFLDOL]LQJLQ Life Goals Life Goals How to Communicate Effectively Dating Tips How to Overcome Obstacles Teens at Risk Self-Development Communications Powerpoint Presentation Financial Planning Self-Leadership Time Management Career and Business -

The Throng of 2600 Jewish

B”H Va The Shul weekly magazine Sponsored By Mr. & Mrs. Martin (OBM) and Ethel Sirotkin and Dr. & Mrs. Shmuel and Evelyn Katz Shabbos Parshas Vayakhel Shabbos Shekalim Shabbos Mevarchim 24 - 25 Adar 1 March 1-2 CANDLE LIGHTING: 6:04 pm Shabbos Ends: 6:57 pm Roch Chodesh Adar 2 Thursday - Friday March 7-8 Molad - New Moon Wednesday, March 6 12:41 (16 chalakim) PM Te Shul - Chabad Lubavitch - An institution of Te Lubavitcher Rebbe, Menachem M. Schneerson (May his merit shield us) Over Tirty fve Years of Serving the Communities of Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands, Indian Creek and Surfside 9540 Collins Avenue, Surfside, Fl 33154 Tel: 305.868.1411 Fax: 305.861.2426 www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] www.theshulpreschool.org www.cyscollege.org The Shul Weekly Magazine Everything you need for every day of the week Contents Nachas At A Glance Weekly Message 3 Thoughts on the Parsha from Rabbi Sholom D. Lipskar CYS College History Series lecture with Professor Henry Abramson of Touro College who delivered a very interesting A Time to Pray 5 lecture about the Ramchal, Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzato. Check out all the davening schedules and locations throughout the week Celebrating Shabbos 6-7 Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you need for an “Over the Top” Shabbos experience Community Happenings 8 - 9 Sharing with your Shul Family Inspiration, Insights & Ideas 10-17 Bringing Torah lessons to LIFE Get The Picture 17- 25 The full scoop on all the great events around town The ABC’s of Aleph 26-27 Serving Jews in institutional and limited environments.