Project for a Judaism-Inspired Transpersonal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shlomo Aharon Kazarnovsky 1

HaRav HaChossid Rabbi Sholmo Aharon Kazarnovsky Memento From the Wedding of Yankele & Frumie Eidelman 10th Day of Tammuz 5781 ב״ה We thankfully acknowledge* the kindness that Hashem has granted us. Due to His great kindness, we merited the merit of the marriage of our children, the groom Yankele and his bride, Frumie. Our thanks and our blessings are extended to the members of our family, our friends, and our associates who came from near and far to join our celebration and bless our children with the blessing of Mazal Tov, that they should be granted lives of good fortune in both material and spiritual matters. As a heartfelt expression of our gratitude to all those participating in our celebration — based on the practice of the Rebbe Rayatz at the wedding of the Rebbe and Rebbetzin of giving out a teshurah — we would like to offer our special gift: a compilation about the great-grandfather of the bride, HaRav .Karzarnovsky ע״ה HaChossid Reb Shlomo Aharon May Hashem who is Good bless you and all the members of Anash, together with all our brethren, the Jewish people, with abundant blessings in both material and spiritual matters, including the greatest blessing, that we proceed from this celebration, “crowned with eternal joy,” to the ultimate celebration, the revelation of Moshiach. May we continue to share in each other’s simchas, and may we go from this simcha to the Ultimate Simcha, the revelation of Moshiach Tzidkeinu, at which time we will once again have the zechus to hear “Torah Chadashah” from the Rebbe. -

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

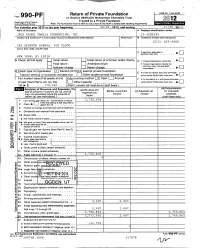

Return of Private Foundation

l efile GRAPHIC p rint - DO NOT PROCESS As Filed Data - DLN: 93491015004014 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990 -PF or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation Department of the Treasury 2012 Note . The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements Internal Revenue Service • . For calendar year 2012 , or tax year beginning 06 - 01-2012 , and ending 05-31-2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number CENTURY 21 ASSOCIATES FOUNDATION INC 22-2412138 O/o RAYMOND GINDI ieiepnone number (see instructions) Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite U 22 CORTLANDT STREET Suite City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here F NEW YORK, NY 10007 G Check all that apply r'Initial return r'Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here (- r-Final return r'Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, r Address change r'Name change check here and attach computation H Check type of organization FSection 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation r'Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust r'Other taxable private foundation J Accounting method F Cash F Accrual E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end und er section 507 ( b )( 1 )( A ), c hec k here F of y e a r (from Part 77, col. (c), Other (specify) _ F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination line 16)x$ 4,783,143 -

Return of Private Foundation

Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545 -0052 Fonn 990 -PFI or Section 4947( a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Treated as a Private Foundation 2012 Department of the Treasury Internal Revenue Sennce Note The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements For calendar year 2012 or tax year beginning 12/01 , 2012 , and endii 11/30. 2013 Name of foundation A Employer identification number JACK ADJMT FAMILY FOUNDATION. INC. 13-3202295 Number and street ( or P 0 box number If mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/suite B Telephone number ( see instructions) (212) 629-9600 463 SEVENTH AVENUE, 4TH FLOOR City or town, state , and ZIP code C If exemption application is , q pending , check here . NEW YORK, NY 10018 G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1 Foreign organ izations . check here El Final return Amended return 2 Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, check here and attach Address change Name chang e computation . • • • • • • . H Check type of organization X Section 501 ( cJ 3 exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated Section 4947 ( a )( 1 nonexem pt charitable trust Other taxable p rivate foundation under section 507(bxlXA ), check here . Ill. El I Fair market value of all assets at end J Accountin g method X Cash L_J Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination of year (from Part Il, col. (c), line 0 Other ( specify) _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ under section 507(b )( 1)(B), check here 16) 10- $ 17 0 , 2 4 0 . -

A Clergy Resource Guide

When Every Need is Special: NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING A Clergy Resource Guide For the best in child, family and senior services...Think JSSA Jewish Social Service Agency Rockville (Wood Hill Road), 301.838.4200 • Rockville (Montrose Road), 301.881.3700 • Fairfax, 703.204.9100 www.jssa.org - [email protected] WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING PREFACE This February, JSSA was privileged to welcome 17 rabbis and cantors to our Clergy Training Program – When Every Need is Special: Navigating Special Needs in the Synagogue Environment. Participants spanned the denominational spectrum, representing communities serving thousands throughout the Washington region. Recognizing that many area clergy who wished to attend were unable to do so, JSSA has made the accompanying Clergy Resource Guide available in a digital format. Inside you will find slides from the presentation made by JSSA social workers, lists of services and contacts selected for their relevance to local clergy, and tachlis items, like an ‘Inclusion Check‐list’, Jewish source material and divrei Torah on Special Needs and Disabilities. The feedback we have received indicates that this has been a valuable resource for all clergy. Please contact Rabbi James Kahn or Natalie Merkur Rose with any questions, comments or for additional resources. L’shalom, Rabbi James Q. Kahn, Director of Jewish Engagement & Chaplaincy Services Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8356 Natalie Merkur Rose, LCSW‐C, LICSW, Director of Jewish Community Outreach Email [email protected]; Phone 301.610.8319 WHEN EVERY NEED IS SPECIAL – NAVIGATING SPECIAL NEEDS IN A CONGREGATIONAL SETTING RESOURCE GUIDE: TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1: SESSION MATERIALS FOR REVIEW PAGE Program Agenda ......................................................................................................... -

Mr. & Mrs. Ryan and Dinie Shapiro

B”H The Shul weekly magazine Weekly Magazine Sponsored By Mr. & Mrs. Martin (OBM) and Ethel Sirotkin and Dr. & Mrs. Shmuel and Evelyn Katz Shabbos Chol Hamoed Nissan 18 -19 April 14 - April 15 CANDLE LIGHTING: 7:26 PM SHABBOS ENDS: 8:19 PM Shvii - Acharon Shel Pesach Nissan 20 -22 April 16 -18 Candle lighting 1st Night: 7:26 pm Candle Lighting 2nd Night: After 8:20 Pm (from pre-existing flame) Over Tirty Six Years of Serving the Communities of Bal Harbour, Bay Harbor Islands, Indian Creek and Surfside 9540 Collins Avenue, Surfside, Fl 33154 Tel: 305.868.1411 Fax: 305.861.2426 www.TeShul.org Email: [email protected] The Shul Weekly Magazine Everything you need for every day of the week Contents Nachas At A Glance Weekly Message 3 Thoughts on the Parsha from Rabbi Sholom D. Lipskar Counselors of Camp Yeka set out across Celebrating Shabbos Ukraine, visiting 13 cities and reaching Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you 4 - 5 need for an “Over the Top” Shabbos experience over 1200 children with a model Matzah Bakery experience. Celebrating Pesach 6 - 7 Schedules, classes, articles and more... Everything you need for an “Over the Top” Yom Tov experience Community Happenings 8-9 Sharing with your Shul Family A Time to Pray 10 Check out all the davening schedules and locations throughout the week 11 -18 Inspiration, Insights & Ideas Bringing Torah lessons to LIFE Get The Picture 19 -24 The full scoop on all the great events around town Meyer Youth Center 25 The full scoop on all the Youth events around town 26 French Connection Refexions sur la Paracha Latin Link 27 Refexion Semanal In a woman’s world 28 Issues of relevance to the Jewish woman The ABC’s of Aleph 29 Serving Jews in institutional and limited environments. -

“Y Nosotros Somos Tu Pueblo Y El Rebaño De Tu Pastoreo”

AÑO 19 / N° 67 / TISHREI 5779/ PRIMAVERA 2018 “Y nosotros somos Tu pueblo y el rebaño de Tu pastoreo” Shaná Tová Umetuká 2 3 contenido 67 15 destaque 6 EDITORIAL ¿ESTÁS PARA COSER BOTONES? -Rabino Eliezer Shemtov 10 CARTA DEL REBE 33 NADIE ES INCAPAZ DE LOGRAR SU OBJETIVO 22 TORÁ Y CIENCIA ¿CUÁNTOS AÑOS TIENE EL UNIVERSO DE ACUERDO AL JUDAÍSMO? -Tzvi Freeman 46 SALUD REHABILITANDO VIDAS DE LAS ADICCIONES 46 -Miriam Karp 50 MUJER JUDÍA ¿QUÉ HACER CUANDO NOS DECEPCIONAN? -Rosally Saltsman 53 HISTORIAS JASÍDICAS EL BURRO INGENIOSO -Yaakov Lieder NUESTRA TAPA Publicación de Beit Jabad Uruguay. Pereyra de La Luz 1130 Los comienzos son siempre lindos; sueños, esperanza y fuerzas renovadas. Rosh 11300, Montevideo-Uruguay. Tel.: (+598) 26286770 Hashaná no es meramente el aniversario E-mail: [email protected]. de la creación del universo; según los Director: Rabino Eliezer Shemtov místicos judíos, en Rosh Hashaná Di-s Editor: Daniel Laizerovitz vuelve a crear al hombre y Su universo, Traducciones: Marcos Jerouchalmi dotándoles de nuevas fuerzas. Que sea un Foto de tapa: Johanna Avayú año de bendición, éxitos y satisfacciones para todos. Se imprime en MERALIR S.A. ¡Mashíaj ya! D.L.: Nº 369.704, Guayabo 1672 ¡Shaná Tová Umetuká! Agradecemos a www.chabad.org por habernos autorizado a reproducir varios de los artículos publicados en este número. Si sabe de alguien que quiera FE DE ERRATAS: conocer la revista Kesher y no la recibe, o si usted cambió de dirección, le Se hace constar que en la última rogamos que nos lo haga saber de inmediato al edición de Kesher (No 66), pág. -

Posmvist Rhetoric and Its Functions in Haredi Orthodoxy

posmviST rhetoric and its functions in haredi orthodoxy AlanJ. Yuter Haredi, or so-called "ultra-Orthodox/ Jewry contends that it is the most strictand thereforethe most authenticexpression of JewishOrtho doxy. Its authenticity is insured by the devotion and loyalty of its adherents to its leading sages or gedolim, "great ones." In addition to the requirementsof explicit Jewish law, and, on occasion, in spite of those requirements, theHaredi adherent obeys theDaas Torah, or Torah views ofhis or hergedolim. By viewingDaas Torah as a normwithin theJewish legal order,Haredi Judaismreformulates the Jewish legal order inorder to delegitimize thosehalakhic voiceswhich believe thatJewish law does not a require radical countercultural withdrawal from the condition ofmoder nity.According toHaredi Judaism,the culture which Eastern European Jewryhas createdto safeguardthe Torah must beguarded so thatthe Torah observance enshrined in that culture is not violated. Haredi Judaism, often called "ultra-Orthodox Judaism,"1 projects itself as the most strict and most authentic expression in contempo as rary Jewish life. This strictness is expressed in behavior patterns well as in the ideology which supports these patterns. Since Haredi as in culture regards itself the embodiment of the Judaism encoded canon the "Book," or the sacred literary of Rabbinic Judaism, the JewishPolitical Studies Review 8:1-2 (Spring 1996) 127 This content downloaded by the authorized user from 192.168.72.231 on Tue, 20 Nov 2012 06:41:14 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions 128 Alan /. Yuter canon explication of the Haredi reading of Rabbinic Judaism's yields a definition of Haredi Judaism's religious ideology. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

UNVERISTY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative In

UNVERISTY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in Music by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 © Copyright by Zachary Alexander Klein 2019 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Spiritual Narrative in Sound and Structure of Chabad Nigunim by Zachary Alexander Klein Doctor of Philosophy in Music University of California, Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Richard Dane Danielpour , Co-Chair Professor David Samuel Lefkowitz, Co-Chair In the Chabad-Lubavitch chasidic community, the singing of religious folksongs called nigunim holds a fundamental place in communal and individual life. There is a well-known saying in Chabad circles that while words are the pen of the heart, music is the pen of the soul. The implication of this statement is that music is able to express thoughts and emotions in a deeper way than words could on their own could. In chasidic thought, there are various spiritual narratives that may be expressed through nigunim. These narratives are fundamental in understanding what is being experienced and performed through singing nigunim. At times, the narrative has already been established in Chabad chasidic literature and knowing the particular aspects of this narrative is indispensible in understanding how the nigun unfolds in musical time. ii In other cases, the particular details of this narrative are unknown. In such a case, understanding how melodic construction, mode, ornamentation, and form function to create a musical syntax can inform our understanding of how a nigun can reflect a particular spiritual narrative. This dissertation examines the ways in which musical syntax and spiritual parameters work together to express these various spiritual narratives in sound and structure of nigunim. -

El Infinito Y El Lenguaje En La Kabbalah Judía: Un Enfoque Matemático, Lingüístico Y Filosófico

El Infinito y el Lenguaje en la Kabbalah judía: un enfoque matemático, lingüístico y filosófico Mario Javier Saban Cuño DEPARTAMENTO DE MATEMÁTICA APLICADA ESCUELA POLITÉCNICA SUPERIOR EL INFINITO Y EL LENGUAJE EN LA KABBALAH JUDÍA: UN ENFOQUE MATEMÁTICO, LINGÜÍSTICO Y FILOSÓFICO Mario Javier Sabán Cuño Tesis presentada para aspirar al grado de DOCTOR POR LA UNIVERSIDAD DE ALICANTE Métodos Matemáticos y Modelización en Ciencias e Ingeniería DOCTORADO EN MATEMÁTICA Dirigida por: DR. JOSUÉ NESCOLARDE SELVA Agradecimientos Siempre temo olvidarme de alguna persona entre los agradecimientos. Uno no llega nunca solo a obtener una sexta tesis doctoral. Es verdad que medita en la soledad los asuntos fundamentales del universo, pero la gran cantidad de familia y amigos que me han acompañado en estos últimos años son los co-creadores de este trabajo de investigación sobre el Infinito. En primer lugar a mi esposa Jacqueline Claudia Freund quien decidió en el año 2002 acompañarme a Barcelona dejando su vida en la Argentina para crear la hermosa familia que tenemos hoy. Ya mis dos hermosos niños, a Max David Saban Freund y a Lucas Eli Saban Freund para que logren crecer y ser felices en cualquier trabajo que emprendan en sus vidas y que puedan vislumbrar un mundo mejor. Quiero agradecer a mi padre David Saban, quien desde la lejanía geográfica de la Argentina me ha estimulado siempre a crecer a pesar de las dificultades de la vida. De él he aprendido dos de las grandes virtudes que creo poseer, la voluntad y el esfuerzo. Gracias papá. Esta tesis doctoral en Matemática Aplicada tiene una inmensa deuda con el Dr. -

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik Z"L

The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph B. Soloveitchik z"l Byline: Rabbi Dr. Nathan Lopes Cardozo is Dean of the David Cardozo Academy in Jerusalem. Thoughts to Ponder 529 The Genius and Limitations of Rabbi Joseph Ber Soloveitchik z”l * Nathan Lopes Cardozo Based on an introduction to a discussion between Professor William Kolbrener and Professor Elliott Malamet (1) Honoring the publication of Professor William Kolbrener’s new book “The Last Rabbi” (2) Yad Harav Nissim, Jerusalem, on Feb. 1, 2017 Dear Friends, I never had the privilege of meeting Rav Soloveitchik z”l or learning under him. But I believe I have read all of his books on Jewish philosophy and Halacha, and even some of his Talmudic novellae and halachic decisions. I have also spoken with many of his students. Here are my impressions. No doubt Rav Soloveitchik was a Gadol Ha-dor (a great sage of his generation). He was a supreme Talmudist and certainly one of the greatest religious thinkers of our time. His literary output is incredible. Still, I believe that he was not a mechadesh – a man whose novel ideas really moved the Jewish tradition forward, especially regarding Halacha. He did not solve major halachic problems. This may sound strange, because almost no one has written as many novel ideas about Halacha as Rav Soloveitchik (3). His masterpiece, Halakhic Man, is perhaps the prime example. Before Rav Soloveitchik appeared on the scene, nobody – surely not in mainstream Orthodoxy – had seriously dealt with the ideology and philosophy of Halacha (4). Page 1 In fact, the reverse is true.