Rabbi Nachman of Breslev and Cognitive Therapy: a Short

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Difference Between Blessing (Bracha) and Prayer (Tefilah)

1 The Difference between Blessing (bracha) and Prayer (tefilah) What is a Bracha? On the most basic level, a bracha is a means of recognizing the good that God has given to us. As the Talmud2 states, the entire world belongs to God, who created everything, and partaking in His creation without consent would be tantamount to stealing. When we acknowledge that our food comes from God – i.e. we say a bracha – God grants us permission to partake in the world's pleasures. This fulfills the purpose of existence: To recognize God and come close to Him. Once we have been satiated, we again bless God, expressing our appreciation for what He has given us.3 So, first and foremost, a bracha is a "please" and a "thank you" to the Creator for the sustenance and pleasure He has bestowed upon us. The Midrash4 relates that Abraham's tent was pitched in the middle of an intercity highway, and open on all four sides so that any traveler was welcome to a royal feast. Inevitably, at the end of the meal, the grateful guests would want to thank Abraham. "It's not me who you should be thanking," Abraham replied. "God provides our food and sustains us moment by moment. To Him we should give thanks!" Those who balked at the idea of thanking God were offered an alternative: Pay full price for the meal. Considering the high price for a fabulous meal in the desert, Abraham succeeded in inspiring even the skeptics to "give God a try." Source of All Blessing Yet the essence of a bracha goes beyond mere manners. -

Chassidus on the Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) VA’ES CHA NAN _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah Deciphered Messages The Torah tells us ( Shemos 19:19) that when the Jewish people gathered at Mount Sinai to receive the Torah , “Moshe spoke and Hashem answered him with a voice.” The Gemora (Berochos 45a) der ives from this pasuk the principle that that an interpreter should not speak more loudly than the reader whose words he is translating. Tosafos immediately ask the obvious question: from that pasuk we see actually see the opposite: that the reader should n ot speak more loudly than the interpreter. We know, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, that Moshe’s nevua (prophecy) was different from that of the other nevi’im (prophets) in that “the Shechina was speaking through Moshe’s throat”. This means that the interpretation of the nevuos of the other nevi’im is not dependent on the comprehension of the people who hear it. The nevua arrives in this world in the mind of the novi and passes through the filter of his perspectives. The resulting message is the essence of the nevua. When Moshe prophesied, however, it was as if the Shechina spoke from his throat directly to all the people on their particular level of understanding. Consequently, his nevuos were directly accessible to all people. In this sense then, Moshe was the rea der of the nevua , and Hashem was the interpreter. -

<I>Hitbodedut</I> for a New Age: Adaptation of Practices Among the Followers of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav

Hitbodedut for a New Age Adaptation of Practices among the Followers of Rabbi Nachman of Bratslav Tomer Persico AbstrAct: The quest for personal and inner spiritual transformation and development is prevalent among spiritual seekers today and constitutes a major characteristic of contemporary spirituality and the New Age phenomenon. Religious leaders of the Bratslav community endeavor to satisfy this need by presenting adjusted versions of hitbodedut meditation, a practice that emphasizes solitary and personal connection with the divine. As is shown by two typical examples, popular Bratslav teachers today take full advantage of the opportunity to infuse the hitbodedut with elements not found in Rabbi Nachman’s teachings and to dispense with some elements that were. The article addresses the socio-political rationale at the root of these teachers’ novel interpretation of Bratslav hitbodedut and the ways they attempt to deal with the complications that arise out of their work. Keywords: acculturation, Bratslav, contemporary spirituality, hitbodedut, Israel, mysticism, New Age, Rabbi Nachman The Bratslav Hasidic community is currently experiencing an unprece- dented burgeoning. As one of the primary sites for welcoming secular Jews “back into the fold” of observant Judaism, as a fruitful wellspring of contemporary cultural creation, and as the organizing and operating force behind the annual Rosh Hashanah pilgrimage to Uman, Ukraine, the field of its influence is wide (Baumgarten 2012; Mark 2011). The sect was founded by Rabbi Nachman (1772–1810) from the town of Bratslav (Bres- lov) in Ukraine, an early Hasidic leader. As might be expected, just as the flowering of this old Hasidic commu- nity is itself new and surprising, many of the phenomena characteristic of Israel Studies Review, Volume 29, Issue 2, Winter 2014: 99–117 © Association for Israel Studies doi: 10.3167/isr.2014.290207 • ISSN 2159-0370 (Print) • ISSN 2159-0389 (Online) 100 | Tomer Persico current Bratslav practices are novel and would surprise a veteran Bratslav Hasid. -

Metamorphoses of a Platonic Theme in Jewish Mysticism

MOSHE IDEL METAMORPHOSES OF A PLATONIC THEME IN JEWISH MYSTICISM 1. KABBALAH AND NEOPLATONISM Both the early Jewish philosophers – Philo of Alexandria and R. Shlomo ibn Gabirol, for example – and the medieval Kabbalists were acquainted with and influenced by Platonic and Neoplatonic sources.1 However, while the medieval philosophers were much more systematic in their borrowing from Neoplatonic sources, especially via their transformations and transmissions from Arabic sources and also but more rarely from Christian sources, the Kabbalists were more sporadic and fragmentary in their appropriation of Neoplatonism. Though the emergence of Kabbalah has often been described by scholars as the synthesis of Neoplatonism and Gnosticism,2 I wonder not only about the role attributed to Gnosticism in the formation of early Kabbalah, but also about the possi- bly exaggerated role assigned to Neoplatonism. Not that I doubt the im- pact of Neoplatonism, but I tend to regard the Neoplatonic elements as somewhat less formative for the early Kabbalah than what is accepted by scholars.3 We may, however, assume a gradual accumulation of Neoplatonic 1 G. Scholem, ‘The Traces of ibn Gabirol in Kabbalah’, Me’assef Soferei Eretz Yisrael (Tel- Aviv, 1960), pp. 160–78 (Hebrew); M. Idel, ‘Jewish Kabbalah and Platonism in the Middle Ages and Renaissance’, in Neoplatonism and Jewish Thought, ed. L. E. Goodman (Albany: SUNY Press, 1993), pp. 319–52; M. Idel, ‘The Magical and Neoplatonic Interpretations of Kabbalah in the Renaissance’, Jewish Thought in the Sixteenth Century, ed. B. D. Cooperman (Cambridge, MA, 1983), pp. 186–242. 2 G. Scholem, Origins of the Kabbalah (tr. -

Mattos Chassidus on the Massei ~ Mattos Chassidus on the Parsha +

LIGHTS OF OUR RIGHTEOUS TZADDIKIM בעזרת ה ' יתבר A Tzaddik, or righteous person , makes everyone else appear righteous before Hashem by advocating for them and finding their merits. Kedushas Levi, Parshas Noach (Bereishis 7:1) MATTOS ~ MASSEI _ CHASSIDUS ON THE PARSHA + Dvar Torah – Mattos Keep Your Word The Torah states (30:3), “If a man takes a vow or swears an oath to G -d to establish a prohibition upon himself, he shall not violate his word; he shall fulfill whatever comes out of his mouth.” In relation to this passuk , the Midrash quotes from Tehillim (144:4), “Our days are like a fleeting shadow.” What is the connection? This can be explained, says Rav Levi Yitzchok, according to a Gemara ( Nedarim 10b), which states, “It is forbidden to say, ‘ Lashem korban , for G-d − an offering.’ Instead a person must say, ‘ Korban Lashem , an offering for G -d.’ Why? Because he may die before he says the word korban , and then he will have said the holy Name in vain.” In this light, we can understand the Midrash. The Torah states that a person makes “a vow to G-d.” This i s the exact language that must be used, mentioning the vow first. Why? Because “our days are like a fleeting shadow,” and there is always the possibility that he may die before he finishes his vow and he will have uttered the Name in vain. n Story The wood chopper had come to Ryczywohl from the nearby village in which he lived, hoping to find some kind of employment. -

Doing Jewish at Burning Man: a Scholarly Personal Narrative On

DOING JEWISH AT BURNING MAN: A SCHOLARLY PERSONAL NARRATIVE ON IDENTITY, COMMUNITY, AND SPIRITUALITY By Becca Grumet ________________________________________________________________________ Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Jewish Nonprofit Management Hebrew Union College - Jewish Institute of Religion Spring 2016 HEBREW UNION COLLEGE - JEWISH INSTITUTE OF RELIGION LOS ANGELES SCHOOL ZELIKOW SCHOOL OF JEWISH NONPROFIT MANAGEMENT DOING JEWISH AT BURNING MAN: A SCHOLARLY PERSONAL NARRATIVE ON IDENTITY, COMMUNITY, AND SPIRITUALITY By Becca Grumet Approved By: ______________________ Advisor _______________________ ZSJNM Director Table of Contents Abstract 1 Acknowledgements 2 Introduction 3 Methodology 7 Background Overview of Burning Man 9 Religion and Spirituality in Popular Culture 11 Spirituality by the Numbers at Burning Man 14 Jews at Burning Man 15 What is Jewish Spirituality? 17 Chapter 1: Welcome Home 19 Chapter 2: Hitbotdedut 25 Chapter 3: Honey Moo-Moos Jewish identity among Honeys 30 Milk + Honey camp identity 34 Chapter 4: Let’s Get Spiritual Friday Night Shabbat 43 Spirituality Among Honey Moo-Moos 56 Spirituality at The Temple 59 Spirituality at The Man 62 Conclusions & Recommendations Milk + Honey as Valuable for Jewish Identity and Community 64 Burning Man as Spiritual Hub 66 No Tent Jewish Community 68 Outcomes of No Tent Jewish Community 71 Accepting of Fluid Organizational Identity 73 References 76 1 Abstract On August 30th, 2016, I boarded a tiny plane at LAX to Reno, Nevada, and then a packed bus to the Burning Man Festival in the Black Rock Desert. I stayed with a theme camp called Milk + Honey for one week, which is known for its giant Friday night Shabbat service and dinner open to all. -

Sefer Devekut the Book of Attachment (To G-D) a Selection from the Book, “Walking in the Fire”

KosherTorah.com Sefer Devekut The Book of Attachment (To G-d) A Selection from the book, “Walking In The Fire” The Prophetic/Meditative Traditions (Kabbalah) of Bonding With G-d A Work by HaRav Ariel Bar Tzadok Copyright © 2004 by Ariel Bar Tzadok. All rights reserved. Yeshivat Benei Nviim – KosherTorah.com 18375 Ventura Blvd. Suite 314 Tarzana, CA. 91356 USA email: [email protected] Phone: (818) 345-0888 1 Copyright © 1993 - 2004 by Ariel Bar Tzadok. All rights reserved. KosherTorah.com Operations of the Mind/Soul and Its Cleansing Introduction, Part 1 – The Concept & The Halakha "And you who bond to HaShem your G-d are all alive day.” (Devarim 4, 4) "Respect HaShem your G-d, Him shall you serve, to Him shall you bond and His Name shall you praise." (Devarim 10, 20) "You shall walk after HaShem your G-d, Him shall you respect, His mitzvot shall you observe, to His Voice shall you listen, Him shall you serve, and to Him shall you bond.” (Devarim 13, 5) These pasukim and others like it outline for us the Torah commandment to bond with G-d. Now, as one can imagine the idea of bonding with G-d is rather nebulous and subject to various interpretations. Yet, our Sages have been quiet precise in explaining to us the meaning of the bonding. On one hand, being that G-d is called a Consuming Fire (Dev 4:24, 9:3), and one who draws too close to the flames can be burnt, one should instead bond with the Sages of Israel. -

9 Sivan 1807.Dwd

SIVAN Life's splendor forever lies in wait 1 Sivan about each one of us in all its fullness, but veiled from view, deep down, Day Forty-five, making six weeks and three days, of the invisible, far off. It is there, though, Omer not hostile, not reluctant, not deaf. If Rosh Hodesh Sivan Hillula of Bohemian-born Austrian writer Franz Kafka, you summon it by the right word, by its pictured at right. Kafka was an admirer of right name, it will come. –Franz Kafka anarcho-communist theoretician Pyotr Kropotkin. As an elementary and secondary school student, Kafka wore a red carnation in his lapel to show his support for socialism. (1 Sivan 5684, 3 June 1924) Hillula of Polish-born U.S. labor lawyer Jack Zucker. When Senator Joseph McCarthy impugned Zucker’s patriotism, Zucker retorted, “I have more patriotism in my little finger than you have in your entire body!” (1 Sivan 5761, 23 May 2001) Hillula of Samaritan High Priest Levi ben Abisha ben Pinhas ben Yitzhaq, the first Samaritan High Priest to visit the United States (1 Sivan 5761, 23 May 2001) Hillula of U.S. labor leader Gus Tyler, pictured at right. Born Augustus Tilove, he adopted the sur- name Tyler as a way of honoring Wat Tyler, the leader of a 14th-century English peasant rebellion. (1 Sivan 5771, 3 June 2011) Hillula of Annette Dreyfus Benacerraf, niece of 1965 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine Jacques Monod and wife of 1980 Nobel laureate in Physiology or Medicine Baruj Benacerraf (1 Sivan 5771, 3 June 2011) 2 Sivan Day Forty-six, making six weeks and four days, of the Omer Hillula of Rebbe Israel Hager of Vizhnitz, pictured at near right. -

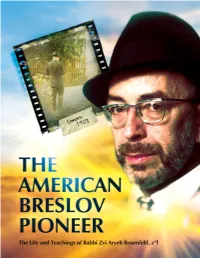

Rabbi-Rosenfeld-Bio-1.Pdf

The American Breslov Pioneer The Life and Teachings of Rabbi Zvi Aryeh Rosenfeld z”l (1922-1978) A modern-day pioneer who brought Breslov Chassidus to America and nurtured its growth for more than thirty years Published by BRESLOV RESEARCH INSTITUTE JERUSALEM/NY 2 / The American Breslov Pioneer COPYRIGHT ©2020 BRESLOV RESEARCH INSTITUTE ISBN: No part of this book may be translated, reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. For further information: Breslov Research Institute POB 5370, Jerusalem, Israel 91053 or Breslov Research Institute POB 587, Monsey, NY 10952-0587 or Breslov Research Institute POB 11, Lakewood, NJ 08701 www.breslov.org e-mail: [email protected] PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD / 3 MAIN DEDICATION $10,000 YOUR DEDICATION TEXT HERE 4 / The American Breslov Pioneer FRONT PAGE BOOK DEDICATION $5,000 YOUR DEDICATION TEXT HERE PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD / 5 TABLE OF CONTENTS PUBLISHER’S FOREWORD .............................................................................................................. 4 PREFACE ....................................................................................................................................... 6 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................. 9 PROLOGUE ................................................................................................................................... -

Work at Not Needing Approval from Anyone and You Will

CHESHVAN “Work at not needing THEMES OF CHESVAN approval from anyone • Sifting through “the muck” • Putting faith in your efforts, and you will be free to believing they’ll blossom be who you really are.” • Following through on our intentions – Rebbe Nachman of Breslov1 • Grounding and breakthroughs 1. The homegirls At The Well would not put a teaching from a dude in our newsletter unless we knew he was a total righteous brother. Rebbe Nachman of Breslov is this guy. Known for merging the Jewish mystical elements with the ancient traditions in the Torah, the Rebbe invited us to speak to God as if we were talking to our best friend. So, in the spirit of this teaching, imagine if God really was just “one of us, on a bus, trying to make her way home.” 1 SPIRITUAL ENERGY OF CHESHVAN The cooler air and changing leaves inspire a natural turning ancestors returning from spiritual pilgrimages to visit their inwards right about now; the spirit of the Hebrew calendar Rebbes. Tishrei created the ultimate high, the moment of is in sync with this energy of introspection, but also some being closest to the Divine. When the pilgrimage was over spiritual hustle as well. The month of Cheshvan has a rolling and the people journeyed home, it was most likely a time up your sleeves and making good on all of last month’s hard of mourning and shock, a time of depression, or at least a spiritual work flavor to it. We just left Tishrei, the holiest little slumping, as they waded back into the “muck” of life. -

Elements of Jewish Meditation

ELEMENTS OF JEWISH MEDITATION Introduction Jewish meditation is an ancient tradition that elevates Jewish thought, inspires Jewish practice, and deepens Jewish prayer. In its initial stages, Jewish meditation is a way to become more focused and aware. It enables the meditator to free the mind of all judgments, fears, doubts, and limiting ideas so that the voice of the soul is heard. With practice, the experience can be transformational, opening us to experience the Divine Presence during prayer, helping us discover deeper meaning in our lives, and connecting us spiritually to Jewish tradition. Jewish meditation can ultimately lead us to understand the true essence of Y-H-V-H through the practice of deeds of loving kindness and joyful compassion. Through meditation we can become attentive to the Divine imprint on our lives. I hope that Jewish meditation will become your practice for the rest of your life. It takes time to develop and refine a meditation practice. In this process it is useful to have a spiritual partner with whom you can explore the wondrous moments and the difficult ones. It is also important to keep a journal, where you write your thoughts down after each meditation and share them with your spiritual partner. Over the years Jewish meditation can lead to great spiritual transformation. What is Jewish Meditation? Jewish meditation is based in Jewish mysticism, a tradition present throughout Jewish history with strong ties to traditional Judaism. Jewish mysticism seeks to answers basic questions of life, such as the nature of God, the meaning of creation, and the existence of good and evil. -

“Meditation(S)”: One Word, Three Semantics

Meditating in a Jewish perspective “Our sages used to sit an hour before prayer”, says the Mishna. They did so to increase their kavannah, their intention, their mindfulness. We want to apply this to all of our life. Only from a place of openness can we receive. Only from a place of stillness can we see. Only from a place of quietness can we hear. Our meditation tools are hitbonenut (self-inquiry) mussar (ethical discipline), and the teachings of Torah in words and in our body . Our influences include Maimonides, Rabbi Salanter, Rav Kook, and the Aish Kodesh. Meditation strengthens this place of silence, stillness and peace within us, so that we can let the divine light shine through us in our daily lives. Because the concept of Jewish meditation can mean many different things, we offer here some more detailed explanations on the background of the practice, before presenting the specific approach of Nefesh Shalom. “Meditation(s)”: one word, three semantics Enter full screen mode “Meditation” comes from the Latin meditari, which means “exercise” and “reflection”. In its most elementary sense, “meditating” means exerting one’s thoughts in a focused manner: directing one’s mind to a specific object. This object can be intellectual (in the case of philosophical meditations), physical (in the case of Buddhist breath meditation), or divine (in the case of mystical meditation). In these three disciplines, the goal of meditation is completely different: philosophy seeks to understand reality, Buddhism seeks to bring awareness to the functioning of the mind, and mysticism seeks to connect to G.od.