Texas, Banks, and John Nance Garner

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Picking the Vice President

Picking the Vice President Elaine C. Kamarck Brookings Institution Press Washington, D.C. Contents Introduction 4 1 The Balancing Model 6 The Vice Presidency as an “Arranged Marriage” 2 Breaking the Mold 14 From Arranged Marriages to Love Matches 3 The Partnership Model in Action 20 Al Gore Dick Cheney Joe Biden 4 Conclusion 33 Copyright 36 Introduction Throughout history, the vice president has been a pretty forlorn character, not unlike the fictional vice president Julia Louis-Dreyfus plays in the HBO seriesVEEP . In the first episode, Vice President Selina Meyer keeps asking her secretary whether the president has called. He hasn’t. She then walks into a U.S. senator’s office and asks of her old colleague, “What have I been missing here?” Without looking up from her computer, the senator responds, “Power.” Until recently, vice presidents were not very interesting nor was the relationship between presidents and their vice presidents very consequential—and for good reason. Historically, vice presidents have been understudies, have often been disliked or even despised by the president they served, and have been used by political parties, derided by journalists, and ridiculed by the public. The job of vice president has been so peripheral that VPs themselves have even made fun of the office. That’s because from the beginning of the nineteenth century until the last decade of the twentieth century, most vice presidents were chosen to “balance” the ticket. The balance in question could be geographic—a northern presidential candidate like John F. Kennedy of Massachusetts picked a southerner like Lyndon B. -

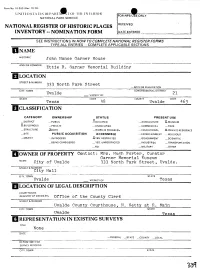

National Register of Historic Places Inventory -- Nomination Form Date Entered

Form No. 10-300 (Rev. 10-74) ^jt UNHLDSTAn.S DLPARTP^K'T Oh TUt, INILR1OR NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVED INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOWTO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS NAME HISTORIC John Nance Garner House AND/OR COMMON Ettie R. Garner Memorial Buildinp [LOCATION STREET& NUMBFR 333 North Park Street _NOT FOR PUBLICATION CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT CITY. TOWN 21 Uvalde VICINITY OF STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Texas Uvalde 463 CLASSIFICATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE ^DISTRICT ^.PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X_MUSEUM X-BUILDING(S) _PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL __PARK —STRUCTURE J&BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL X.PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS —XYES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED — YES: UNRESTRICTED —INDUSTRIAL —TRANSPORTATION _NO —MILITARY —OTHER. OWNER OF PROPERTY Contact: Mrs. Hugh Porter, Curator Garner Memorial Museum NAME City of Uvalde 333 North Park Street, Uvalde STREETS NUMBER City Hall CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde VICINITY OF Texas [LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE. REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC office of the County Clerk STREETS NUMBER Uvalde County Courthouse, N. Getty at E. Main CITY, TOWN STATE Uvalde Texas REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS TITLE None DATE — FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY _LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS CITY, TOWN STATE DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE —EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED X_ORIGINAL SITE ^LcOOD —RUINS ?_ALTERED _MOVED DATE——————— _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBETHE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE From 1920 until his wife's death in 1952, Garner made his permanent home in this two-story, H-shaped, hip-roofed, brick house, which was designed for him by architect Atlee Ayers. -

The Vice President in the U.S. Senate: Examining the Consequences of Institutional Design

The Vice President in the U.S. Senate: Examining the Consequences of Institutional Design. Michael S. Lynch Tony Madonna Asssistant Professor Assistant Professor University of Kansas University of Georgia [email protected] [email protected] January 25, 2010∗ ∗The authors would like to thank Scott H. Ainsworth, Stanley Bach, Ryan Bakker, Sarah A. Binder, Jamie L. Carson, Michael H. Crespin, Keith L. Dougherty, Trey Hood, Andrew Martin, Ryan J. Owens and Steven S. Smith for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Madonna also thanks the University of Georgia American Political Development working group for support and comments, and Rachel Snyder for helpful research assistance. All errors remain the authors. Abstract The constitutional designation of the vice president as the president of the United States Senate is a unique feature of the chamber. It places control over the Senate's rules and precedents under an individual who is not elected by the chamber and receives no direct benefits from the maintenance of its institutions. We argue that this feature of the Senate has played an important, recurring role in its development. The vice president has frequently acted in a manner that conflicted with the wishes chamber majorities. Consequently, the Senate has developed rules and precedents that insulate the chamber from its presiding officer. These actions have made the Senate a less efficient chamber, but have largely freed it from the potential influence of the executive branch. We examine these arguments using a mix of historical and contemporary case studies, as well as empirical data on contentious rulings on questions of order. -

The Vice President's Room

THE VICE PRESIDENT’S ROOM THE VICE PRESIDENT’S ROOM Historical Highlights The United States Constitution designates the vice president of the United States to serve as president of the Senate and to cast the tie-breaking vote in the case of a deadlock. To carry out these duties, the vice president has long had an office in the Capitol Building, just outside the Senate chamber. Earliest known photographic view of the room, c. 1870 Due to lack of space in the Capitol’s old Senate wing, early vice presidents often shared their room with the president. Following the 1850s extension of the building, the Senate formally set aside a room for the vice president’s exclusive use. John Breckinridge of Kentucky was the first to occupy the new Vice President’s Room (S–214), after he gavelled the Senate into session in its new chamber in 1859. Over the years, S–214 has provided a convenient place for the vice president to conduct business while at the Capitol. Until the Russell Senate Office Building opened in 1909, the room was the only space in the city assigned to the vice presi- dent, and it served as the sole working office for such men as Hannibal Hamlin, Chester Alan Arthur, and Theodore Roosevelt. Death of Henry Wilson, 1875 Several notable and poignant events have occurred in the Vice President’s Room over the years. In 1875 Henry Wilson, Ulysses S. Grant’s vice president, died in the room after suffering a stroke. Six years later, following President James Garfield’s assassination, Vice President Chester Arthur took the oath of office here as president. -

DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North

4Z SAM RAYBURN: TRIALS OF A PARTY MAN DISSERTATION Presented to the Graduate Council of the North Texas State University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY By Edward 0. Daniel, B.A., M.A. Denton, Texas May, 1979 Daniel, Edward 0., Sam Rayburn: Trials of a Party Man. Doctor of Philosophy (History), May, 1979, 330 pp., bibliog- raphy, 163 titles. Sam Rayburn' s remarkable legislative career is exten- sively documented, but no one has endeavored to write a political biography in which his philosophy, his personal convictions, and the forces which motivated him are analyzed. The object of this dissertation is to fill that void by tracing the course of events which led Sam Rayburn to the Speakership of the United States House of Representatives. For twenty-seven long years of congressional service, Sam Rayburn patiently, but persistently, laid the groundwork for his elevation to the speakership. Most of his accomplish- ments, recorded in this paper, were a means to that end. His legislative achievements for the New Deal were monu- mental, particularly in the areas of securities regulation, progressive labor laws, and military preparedness. Rayburn rose to the speakership, however, not because he was a policy maker, but because he was a policy expeditor. He took his orders from those who had the power to enhance his own station in life. Prior to the presidential election of 1932, the center of Sam Rayburn's universe was an old friend and accomplished political maneuverer, John Nance Garner. It was through Garner that Rayburn first perceived the significance of the "you scratch my back, I'll scratch yours" style of politics. -

Keven Mcqueen (2001): Offbeat Kentuckians: Richard M. Johnson: One of Franklin D

Keven McQueen (2001): Offbeat Kentuckians: Richard M. Johnson: One of Franklin D. Roosevelt‘s vice presidents, John Nance Garner, famous lamented, "The vice presidency isn’t worth a pitcher of warm spit.” However, on occasion we encounter a vice president whose performance itself isn’t worth a pitcher of warm spit. One of these was Kentucky’s Richard M. Johnson. Johnson was born on October 17, 1780 (some sources claim 1781), when much of Kentucky was still the untamed frontier. The site of his birth was a settlement called Beargrass, now known more familiarly as Louisville. Shortly thereafter, the family moved first to Bryant’s Station, near Lexington, and then to Scott County. According to relatives, when he was a young man Johnson fell in love with a woman who was either a schoolteacher or a seamstress. He wanted to marry her, but his mother forbade the union. Deeply hurt, Johnson vowed she would regret her interference some day. His revenge was many years delayed, but when it finally came it caused a major political and social scandal. Johnson’s career in politics started normally enough. He attended Transylvania University in Lexington, then afterwards studied law. He became a professional lawyer at age 19. Upon developing an interest in politics, he became a member of the General Assembly from 1804–06 and was elected to the House of Representatives in 1807. His career in the House was interrupted by the War of 1812. Johnson, a commissioned Army colonel, led a regiment of volunteers to Canada in 1813, where they fought the British and the Indians. -

Or Attaining Other Committee Members Serving in Higher Offices Accomplishments

Committee Members Serving in Higher Offices or Attaining Other Accomplishments MEMBERS OF CONTINENTAL John W. Jones John Sherman CONGRESS Michael C. Kerr Abraham Baldwin Nicholas Longworth SECRETARIES OF THE TREASURY Elias Boudinot John W. McCormack George W. Campbell Lambert Cadwalader James K. Polk John G. Carlisle Thomas Fitzsimons Henry T. Rainey Howell Cobb Abiel Foster Samuel J. Randall Thomas Corwin Elbridge Gerry Thomas B. Reed Charles Foster Nicholas Gilman Theodore Sedgwick Albert Gallatin William Hindman Andrew Stevenson Samuel D. Ingham John Laurance John W. Taylor Louis McLane Samuel Livermore Robert C. Winthrop Ogden L. Mills James Madison John Sherman John Patten SUPREME COURT JUSTICES Phillip F. Thomas Theodore Sedgwick Philip P. Barboar Fred M. Vinson William Smith Joseph McKenna John Vining John McKinley ATTORNEYS GENERAL Jeremiah Wadsworth Fred M. Vinson, ChiefJustice James P. McGranery Joseph McKenna SIGNER OF THE DECLARATION OF PRESIDENTS A. Mitchell Palmer INDEPENDENCE George H.W. Bush Caesar A. Rodney Elbridge Gerry Millard Fillmore James A. Garfield POSTMASTERS GENERAL DELEGATES TO Andrew Jackson CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION Samuel D. Hubbard James Madison Cave Johnson Abraham Baldwin William McKinley Thomas Fitzsimons James K. Polk Horace Maynard William L. Wilson Elbridge Gerry John Tyler Nicholas Gilman SECRETARIES OF THE NAVY James Madison VICE PRESIDENTS Thomas W. Gilmer John C. Breckinridge SIGNERS OF THE CONSTITUTION Hilary A. Herbert George H.W. Bush OF THE UNITED STATES Victor H. Metcalf Charles Curtis Abraham Baldwin Claude A. Swanson Millard Fillmore Thomas Fitzsimons John Nance Garner Nicholas Gilman SECRETARIES OF THE INTERIOR Elbridge Gerry James Madison Richard M. Johnson Rogers C.B. Morton John Tyler Jacob Thompson SPEAKERS OF THE HOUSE Nathaniel P. -

LOOMING WAR in July 1940, the United States Was Still the Democratic Party

A4 SUNDAY, AUGUST 4, 2019 FROM OUR ARCHIVES LNP | LANCASTER, PA o celebrate 225 years of Lancaster newspapers, we present this week- ly series of 52 front pages from throughout our history. Many feature events that would shape the course of world history. Some feature events of great local importance. Still others simply provide windows into the long-ago lives of Lancaster County residents. Make sure to check in every week, and enjoy this trip through time with LNP. 1940 COVER 31 OF 52 LOOMING WAR In July 1940, the United States was still the Democratic Party. When he was formally across the Swedish border in the lead-up well over a year away from officially elected in 1941, Roosevelt dumped Garner in to a German Luftwaffe bombing mission. getting involved with World War II. favor of former Secretary of Commerce Henry While taking shelter in a tunnel, a bomb was Wallace. However, with the benefit of hindsight, dropped that shot fragments of shrapnel there were signs before that fateful Sunday, Several conflicts in the summer of 1940 — everywhere, including through Losey’s heart, Dec. 7, 1941, that U.S. forces would not stay chiefly the Battle of France, which resulted killing him. neutral for long. One such sign is featured in areas of France falling under German On a more hopeful note, it was reported in on the cover of this July 11, 1940, front page and Italian control — led to one of the first the New Era that the Lancaster Rotary Club of the Lancaster New Era, in the form of an instances of a peacetime draft in the United would be reaching out to the Lancaster, article questioning when President Franklin States. -

Washington, D.C.: Women's National Press Club (Cancelled), January 13

REMARKS VICE PRES I DENT HUBERT HUMP HREY WOME N'S NATIONAL PRESS CLU B JANUARY 13, 1966 Friends and arm-chair Vice Presidents: When your program chairman came to me and suggested that I speak on the subject, "Whatever Happened to Hubert Humphrey?", I was a little startled because this is a question that never oo rries me. I khow. ! have no complaints. Actually si nee becoming Vice President, the question that has been going through_®' mind is: "Whatever happened tot he Press ?" - 2 - What have you been doing these days? Are you happy doing it? Are you really happy? Back in the days of total exposure when I was in the U.S. Senate, I found you bright-eyed, on my trail, eager -- with pad and pendi I in hand. Yet, here I am working longer hours on space, on civil rights, with the nation's mayors, with the President's legislative program -- but w~re are you? I'm really very, very worried about your I MAGE. In fact, I'm so worried I've had a poll taken. The results would discourage you. Your problem is what to do about it. You must do something. If not, by 1972, at the rate you're going there won't be any radio, TV, or newspapers at all. Just word-of-mouth communication. - 3 - In fact, I've even received a memo leaked to me by some disaffected members of the press about the PRESS I MAGE. If I were you, I'd take stock. But, more seriously, let me get down to the question of the evening: "Whatever Happened to Hubert Humphrey?" What have I been up to? I've been "moving, traveling, visiting, climbing, worshipping, hunting, fishing, sailing, boating, hobbying, reading, studying, thinking, sitting, gazing, looking, working, shi rt-sleevi ng, gardening, flying and cooking." But I've also been reciting some poetry to people know. -

The Arsenal of Democracy: President Roosevelt's War Cabinet, 1941

The Arsenal of Democracy: President Roosevelt’s War Cabinet, 1941 Background Guide Written by: Benjamin Goldberg and Siddharth Hariharan, Case Western Reserve University Historical Context A New World Order The United States had little history of involvement in European affairs before 1917, when Germany’s proposal to Mexico for an anti-American alliance drove Congress to declare war on Germany alongside Britain, France, and Italy, finally bringing America into the Great War[1]. The American contribution to ending the war was undeniable, with 4.7 million Americans serving and over 100,000 being killed in action[2], but there were comparatively few demands the United States sought to exact against Germany. The primary U.S. foreign policy goals were outlined by Woodrow Wilson in the Fourteen Points, which covered greater international trade relations, the self-determination of all peoples, and the formation of the League of Nations, an international body with the mission of promoting world peace. The priorities of Britain and France, though, revolved around the removal of Germany as a world power. They demanded that Germany accept responsibility for the war, extracted reparations from them to be paid to the victorious Entente, and placed severe limitations on German military strength[3]. Furthermore, Wilson’s one major policy triumph at Versailles, the formation of the League of Nations, was dampened when it became clear that the United States would be unable to join due to domestic isolationist sentiment[4]. The Great Depression One of the manifestations of postwar optimism was the rise to prominence of the stock market as a cornerstone of the US economy. -

Mondale Lecture on the Vice Presidency, April 10, 1981

Mondale Lecture on the Vice Presidency Hubert H. Humphrey Institute April la, 1981 Today I would like to talk about the Vice Presidency, probably the most maligned public office ever created. In June of 1976, when it was apparent that Governor Carter was going to win the Democratic nomination for President, I flew down to Plains, Georgia, so that he could interview me, as he had several others, in his search for a running mate. I believe he wanted to make sure that the one who shared his ticket was compatible with him, and was the sort of person capable of assuming the Presidency, should that become necessary. After talking with Hubert, and others, about the Vice Presidency, I was interested in the position, but I also had several concerns. I knew of the dismal history of the Vice Presidency, and I was determined that if I decided to take the job I would not be another of its victims. I liked the Senate, I was proud of my achievements there and as I told then Governor Carter, I would not trade them for a ceremonial office. I would only be interested in the office if it could become a useful instrument of government. HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE: The problem with the Vice Presidency has been that those who framed the Constitution prescribed no important duties or powers to the Office of the Vice President. They did not even consider creating the office until two weeks before the Constitutional Convention adjourned. And then, the principal duty they framed for the Vice President was to preside over the Senate and break tie votes. -

John Tyler Ghosts and the Vice Presidency

John Tyler Ghosts and the vice presidency EPISODE TRANSCRIPT Listen to Presidential at http://wapo.st/presidential This transcript was run through an automated transcription service and then lightly edited for clarity. There may be typos or small discrepancies from the podcast audio. LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: Thank you so much. It's so nice to meet you. HARRISON TYLER: All right. LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: This is Harrison Tyler, the grandson of our 10th president, John Tyler. Harrison Tyler is also the great-grandson on his mother's side of our ninth president, William Henry Harrison. Harrison Tyler is 88-years old, and I went to visit him near Richmond, Virginia. Unfortunately, he suffered a horrible stroke two years ago that erased his memory, so he couldn't share recollections of his family history. But he has been reminded since, both by those he knows and those he doesn't know, that he has a special connection to American presidential history. He let me sit with him as he signed letter after letter from people who've written asking for his signature. And he told me about how, just days before, he went to visit the grave of his grandfather. He couldn't remember all the times he had visited in the past. So, he wanted to go back to build a new memory -- and to understand how his own story is intertwined with the story of U.S. history. I'm Lillian Cunningham with The Washington Post, and this is the 10th episode of 'Presidential.' PRESIDENTIAL THEME MUSIC LILLIAN CUNNINGHAM: John Tyler is the vice president who became president himself when William Henry Harrison died in office after only 32 days.